Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, someone who is following the crisis here closely is Eliot Ackerman. He’s the author and former U.S. marine who served five tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan and has just spent two weeks here in Kyiv. Ackerman joined Walter Isaacson to discuss Russia’s new tactics and the role of moral resolve in war.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, HOST: Thank you, Christiane. And Eliot Ackerman, welcome back to the show.

ELIOT ACKERMAN, AUTHOR AND FORMER U.S. MARINE: Thanks for having me, Walter.

ISAACSON: Russia has just said that it’s going to concentrate now on the Eastern Ukraine and try to pull back some of its troops from Kyiv. You’ve just spent two weeks in Kyiv and parts of Ukraine. Tell me why you think this is happening.

ACKERMAN: I think it’s Russia conceding that the initial objectives of its invasion were too large. They do not have what, in military terms we call, the troops tasked to take all of Kyiv, let alone all of Ukraine. I mean, Kyiv, this is a massive city of nearly four million inhabitants before the war. So, the fact that they are planned of Kyiv and trying to focus now in the East and in the South, shows that war is entering a new phase in which the Russians will, I believe, be pursuing a more limited set of objectives.

ISAACSON: You know, you write a piece in “The Atlantic” that, the Russians don’t know how to empower their soldiers. You were a marine in Iraq and in Afghanistan. What’s the difference between the way you felt empowered and the way Russian troops are fighting?

ACKERMAN: So, in NATO countries, we employ what are called mission tactics. And what that means is there is a philosophy of empowerment by which, you know, every small unit leader, from the 21-year-old corporal up to the general officer understands the mission and the intent of the mission. And the reason for that is oftentimes, you know, the best-laid plans don’t work out. And so, in the fog of battle, the chaos of war, when the plan isn’t working, if everyone understands the mission, you have a more adaptable military. And you can create new plans very quickly from the lowest levels up to the highest levels. Now, the Russian model is a far more centralized model where the planning is far more intricate, the decision making is made by a small, much more senior group of officers and that can work very well and be effective. But the challenge is when the mission doesn’t go according to plan at the lower levels, there’s this inability to adapt. And, I think, probably the greatest visual we have on that from this Ukraine war was — if we recall the 40-mile convoy extending North through Kyiv. And I think in the early days, many Ukrainians and observers are so terrified. You know, what is this enormous convoy that’s going towards Kyiv. But in reality, now in hindsight, is that was really an enormous traffic jam. And things haven’t gone according to plan and everyone in that convoy had no ability to adapt. So, ultimately these different war fighting philosophies, we see them translating as a difference in adaptability on the battle field. And the Russians have shown an inability to adapt, particularly in this first month of the war.

ISAACSON: What has the use of javelins and antitank weaponry taught you about how tactics and strategy are shifting in wars like this?

ACKERMAN: Well, you know, this is a really important issue to be watching right now in the war in Ukraine. And so much as we’re seeing a technological shift occur on the battlefield where these antitank missile systems, like the javelin and the British made NLAW, are very capable. And they are destroying the latest Russian tanks. So, these are what are called anti-platform weapons. They’re designed to destroy platforms like tanks, you know, platforms also include things like high-tech fighter planes and very expensive capital shifts. And so, what we’re seeing as a trend is as these anti-platform systems become more effective, they reduce the importance and the centrality of these massive platforms on the battlefield. And the U.S. needs to be paying attention to this because the U.S., in particular, we have a very platform- centric view of warfare where all of our war-fighting capacity is manifested in if you’re in the army in our tanks, if you’re in the air force in our fighter planes, the very expensive F-35 or aircraft carriers if you’re in the navy. So, as we look for future conflicts in U.S. could be engaged in, it’s important to take away this lesson in the Ukraine, which is, we need to be very careful that we’re not confronting an adversary who we perceive as weaker, but who, in fact, has a very strong anti-platform capability that could level the battlefield for us.

ISAACSON: You’re a marine and fought in the battle for Fallujah. Tell me how that contrast to the battle for Kyiv that the Russians were trying to wage.

ACKERMAN: When I fought as a marine in the battle of Fallujah, I was an infantry officer. And our infantry worked very closely with our tanks, the Abrams battle tank, which is a state-of-the-art tank but similar in capability as the Russian tanks. And I watched on numerous occasions we’re advancing into the city, Abram tanks absorb rocket-propelled grenades, which was the best anti-tank weapon the insurgents had against us. Now, those tanks if they — instead of being hit with a rocket-propelled grenade, had been hit with the javelin, they would have been immediately catastrophically destroyed. And so, the efficacy of tanks in an urban environment was really — is called into question when you have these very effective antitank missile systems. And that’s going to be will important to note in any potential battle for a major Ukrainian city whether it’s Kyiv or we’ve already seen this taking place in cities like Mariupol and even Kherson.

ISAACSON: So many analysts said that the Russians would just right in like Blitzkrieg into Kyiv. I think the Russians thought so as well. why did they get it wrong?

ACKERMAN: The big story here in Ukraine, as much as we’ve been talking about technology and the technology is so great, but it is a story of motivation. The Russians have made the enormous mistake of underestimating Ukrainian motivations. Understanding the essential feeling of nationality that Ukrainians have and have particularly developed since 2014 when this war began with the Russians because any Ukrainian you meet will tell you, this war didn’t start February this year, this war started in 2014 when Russia and ex-Crimea. So, the Russians really have underestimated, what I would call, the moral aspects of this conflict. And the Ukrainians are fighting to defend their families and their homes. And so, Napoleon has — who fought many of his battles in that part of the war, he has one of his Maxims, and the maxim he said was the moral to the material in war is as three is to one. And we’re seeing that right now. That the individuals who actually have that three to one advantage are not the Russians. It is the Ukrainians. And I believe they will continue to enjoy that three to one advantage. And I think this was ultimately going to leave them as the victors in this war.

ISAACSON: That moral three to one force multiplier. Is that the just the Ukraine military or is that the grandmothers, the teenagers, the people of Ukraine all being part of a moral force that’s winning this battle?

ACKERMAN: I’ll say — you know, one of the things that’s been most remarkable to me spending time over there, particularly as someone who once considered himself a professional soldier, is that the vast majority of soldiers, you know, the people we’re watching each night on the nightly news, you know, they are not in fact soldiers. They are, you know, filmmakers, bakers, the grandmothers you referred to, young people who’ve left school to volunteer. So, this is really a true national mobilization of the sort that I have never seen in my lifetime, and of the sort I only read about in history books dating back to France’s second world war.

ISAACSON: And now are they totally convinced that they can repel a Russian attack, especially on Kyiv and Central Ukraine?

ACKERMAN: Walter, I was recently in Kyiv and I was talking to a Ukrainian filmmaker who had spent some time actually as a political prisoner. And I made the mistake of saying to him, do you think you’ll make a movie about this after the war. And he leaned in closely and said to me, you know around here, we don’t say after the war. And I say, what do you say? He said around here, we say after the victory.

ISAACSON: Wow. You wrote in “Time Magazine”, that there’s a sentiment in Ukraine that this is not just the Russian leadership, but that this is Russia. The Russian people who are doing it to them. And I’d like to do a quote from that article, “The Russian people have made a bargain with Putin, it’s one they’ve made throughout their history. They have allowed a despot to take away their freedom, but in exchange he’s offered them glory.” To what extent do the Ukrainians feel they’re now at war with the Russian people?

ACKERMAN: The Ukrainians are quick to point ought that if you haven’t been paying attention to this region, there has been 20 plus years of Russian aggression. Whether it’s Chechnya, in Georgia, in Ukraine now, twice. And they believe that the Russian people have enabled Putin for two decades and that Putin is not the problem, that Putin is the symptom of a larger problem and that is Russian aggression. So, the Ukrainians I know and have spoken with feel very strongly that you cannot decouple this conflict from the Russian people themselves. And if you look at polling, polling does show strong majority support within Russia for the war on Ukraine.

ISAACSON: So, when Biden says, this man cannot stay in power, referring to Putin, do you think a change in power in Russia would change this attitude of the Russians in terms of their expansionist views of Ukraine?

ACKERMAN: I think a hope that a simple change of the person on top in Russia is a solution to all of this is probably not realistic. That these are much, much deeper problems with regards to Russian aggression in that part of the world. So, I don’t believe that simply trying to have a strategy that’s solely focused on getting Putin out of power is somehow going to solve the problems that we’re seeing coming out of Russia.

ISAACSON: Those of us who write biographies always wonder about the role of a singular person. And so, I was going to ask you about President Zelenskyy. To what extent has his sense of inspiration, his fortitude helped make it so that Ukraine is — seems to be repelling the Russian invasion? And to what extent would this have happened even with a different leader?

ACKERMAN: The best leaders are really vehicles by which nations are able to express and manifest their collective will. So, I think President Zelenskyy is only as good as the Ukrainian people. But he has shown himself adept at being a vessel to communicate their collective will. And I think the Ukrainian people are very fortunate that they have a leader like Zelenskyy right now. And I think President Zelenskyy is very fortunate that the Ukrainian people have all gotten behind me — behind him.

ISAACSON: President Zelenskyy continually calls for more support from NATO and the United States, including air support. When you were there, were the things you were hoping that the U.S. and the West should be doing and do you think that would be wise for the U.S. to become more involved in this fight?

ACKERMAN: I think whether the U.S. and the West wants to become more involved in this fight or not is sort of beside the point. We are involved in this fight. And it is, I believe, an essential one. It’s one that we haven’t necessarily seen yet in our lifetime. So, the Ukrainians have been very vocal, and rightly so, about the need to gain control of their airspace. We need to be giving the Ukrainians at least the resources to set up their own no-fly zone if we want them to prevail in this war. And I would make — I would argue that it’s essential that they prevail in this war against the Russians. If we, as a, you know, as free people don’t want to see the continued march of authoritarianism across the globe.

ISAACSON: As a marine, what lessons, do you think, that the American military and forces like the marine should take? What have we learned so far from this fighting?

ACKERMAN: You know, Walter, I think we’ll go back to this idea, and it’s really a strategic one of the essential nature of the moral in war. You know, we have in last — less than a year seen the fall of Afghanistan, and now this invasion of Ukraine. And I think, it’s important to tie the two together. In the case Afghanistan, we saw a highly equipped military that had been deeply trained, really invested in over years and years with a very dysfunctional government collapse in a matter of weeks. That was Afghanistan. In Ukraine, we have seen a government that we know we have invested in nearly the same way, have been very reluctant to equip, hold together and shocked the entire world. And the only real difference in those two cases is the moral factor. Whether or not these people wanted to fight. Whether or not they wanted to hold their country together. And I think as Americans and as the West as we look forward and we try to figure out, you know, the strategies that will secure our prosperity, it’s important to keep in mind the moral makeup of the country’s we’re bringing on as partners. So, I think that that is an essential lesson coming out of this war in Ukraine and one that we should all focus on.

ISAACSON: So, looking at how the Ukraine’s defended their freedom and contrasting that with the way the Afghan army didn’t, does that make you think that it was a mistake the way we went into Afghanistan?

ACKERMAN: Well, what it makes me think is, you know, often times we have a tendency to try to disconnect the military aspect of a conflict from the political aspect of a conflict. As we look at a conflict like in Ukraine or in Afghanistan and understand that what we saw in Afghanistan, in terms of the military defeat, it was very much linked into the political dynamics on the ground in Afghanistan. And what we’re seeing in Ukraine right now, which is a remarkable victory with regards to the Russians, in a really remarkable demonstration of capability is directly tied into the politics of Ukraine. And so, any country that just segregates the military from the political and tries to think about them separately is going to wind up making strategic errors.

ISAACSON: If there is a compromise to try to end this war, and it involves Ukraine being neutral in — for swearing being part of NATO, and if it requires giving up control of some of the Donbas and Crimea or making a disputed territory, do you think the Ukrainians will approve something like that?

ACKERMAN: I think it’s — at least at this moment, the battlefield conditions being what they are, I think it’s very difficult to see an outcome by which the Ukrainian people would accept a piece built on terms by which they had to concede the Donbas and concede Crimea back to the Russians. You know, the Ukrainian people, and I think correctly so, viewed themselves as being the winners of this war thus far. And as the winners, they don’t believe they should have to concede anything as the losers who concede. And they view the Russians as the losers. Now, obviously the, you know, Russians have made incursions into Ukraine. But the Ukrainian people are by no way chastened by what’s happened in the last month. And I don’t think President Zelenskyy would have the ability to hand over, even if he wanted to, to hand over territory to the Russians. So, you know, we’re going to have to see how this plays out in the weeks and months ahead. And I anticipate you’re going to see a lot of jockeying on the battlefield for position that could lead to advantages in the negotiating room. But at least, psychologically, right now the Ukrainian don’t — at least the ones that I’ve been talking with don’t feel they need to concede anything. And I think it would be very difficult for President Zelenskyy to do so and politically survive at home.

ISAACSON: Eliot Ackerman, as always, very enlightening. Thank you for joining us.

ACKERMAN: My pleasure. Thanks for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

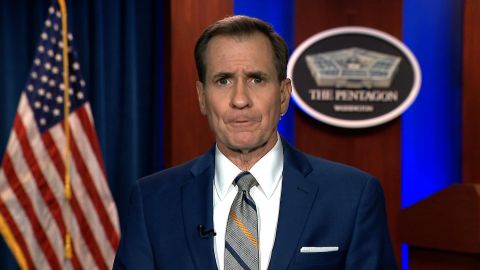

President Zelensky’s chief of staff discusses Putin’s endgame. Pentagon Press Secretary discusses the American effort to support Ukraine. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian discusses his government’s intense diplomatic efforts to continue tightening the screws on Russia. Ackerman discusses Russia’s new tactics and the role of moral resolve in war.

LEARN MORE