Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, HOST: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

JOE BIDEN, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: Your family budget, your ability to fill up your tank, none of it should hinge on whether a dictator

declares war and commits genocide a half-a-world away.

AMANPOUR (voice-over): Inflation bites American families, and President Biden blames a genocidal Vladimir Putin. We unpack the state of a wartime

economy with Jared Bernstein from the White House Council of Economic Advisers

Plus: investigating the barbarity that shocked the world. Correspondent Dan Rivers goes back to Bucha. What it says about Putin’s war.

Then: “White Lies,” the extraordinary and untold story of civil rights activist Walter White. Journalist and author A.J. Baime on White’s double

life and how he changed America.

And what the war in Ukraine means for the whole world, with Zanny Minton Beddoes, editor in chief of “The Economist.”

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

President Biden is up against it ,trying to make his economic case to a nation reeling from inflation, exacerbated by rising energy prices because

of the war in Ukraine. Indeed, he’s tying his economic pain directly to the war, labeling it the Putin price hike.

He’s also now calling the mounting catalogue of Russian horrors around Ukraine genocide. Sanctions leveled by the West are fueling inflation in

all their countries. In the United States, it is at its highest level since 1981. And no doubt ordinary Americans are starting to feel it.

Putin has always banked on causing more hardship than feeling it himself. So, will the West keep up its tough stance? Is the political will there?

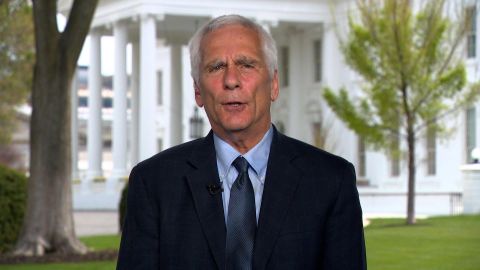

Jared Bernstein is a member of the Council of Economic Advisers for President Biden. And he’s joining me now from the White House.

So, welcome to the program, Mr. Bernstein.

And let’s just take what the president said himself. We have laid out the figures and the facts. How much of it do you agree is the Putin price hike,

as he says?

JARED BERNSTEIN, WHITE HOUSE COUNCIL OF ECONOMIC ADVISERS: You can actually put a number on that if we look at yesterday’s inflation report.

Inflation rose 1.2 percent in the month of March; 70 percent of that was attributable to energy, and almost two-thirds to gasoline alone. If you

look at the pattern at which energy prices have gone up, they very clearly relate to both the run-up to the invasion and the invasion itself.

So the president is spot on when he’s making those points.

AMANPOUR: So let’s talk about what you sometimes label headwinds, because inflation actually existed before the war. And, right now, as we said, it’s

the highest in 40 years or so, or at least since 1981. And I guess that’s 40 years.

It’s about 8.5 percent right now.

BERNSTEIN: Good math.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Yes.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: It’s not my strong suit.

But how is it hurting Americans? And how can you staunch that pain?

BERNSTEIN: It is a real challenge for Americans just across the board. I mean, any of us who have been shopping — I mean, last weekend, I went to

visit my daughter in college. We stayed at the same hotel we’d stayed in the last time we visited her, and it was a very different price tag.

So this is something that, as the president said, is a clear challenge to family budgets.

But I think, amidst these headwinds, what sometimes gets lost is the impact of both some existing tailwinds in the economy, some things that are

helping to lift growth and provide opportunities and incomes to Americans, along with ,perhaps more germane to this part of our conversation, the

president’s actions to lower some of the cost pressures facing consumers, whether it’s gas prices at the pump, whether it’s our actions at the ports

to help get goods from ship to shelf more quickly, whether it’s our trucking initiatives to help improve transportation.

There’s a full broad set of actions we’re taking to help. And they are helping in ways that I can tick off to you. But I think it’s important to

recognize both sides of that equation.

AMANPOUR: So, tick them off, because, obviously, Jared Bernstein, that story is not getting around.

BERNSTEIN: Correct.

AMANPOUR: I mean, I could read you the lamentable poll numbers, which are just pretty awful. And you don’t need my bad math to be able to figure that

out.

The most recent CNN poll says the president’s job approval is at 41 percent. Approval for handling the economy is at 37 percent. So, if you

have these things that you say are already bearing which fruit for the consumer, why is it not showing up in their opinions?

BERNSTEIN: Yes.

Well, these things — so, these — great question. So, these things can both be true. And, in fact, they both are true. There are many important

advantages in our economy, particularly compared to other advanced economies, like many in Europe.

So, for example, GDP growth was about 5.5 percent last year. In Germany, it was about 2 percent. Now, you don’t need GDP growth. What does that mean

for real people? It means jobs, 7.9 million jobs since this president got here, an unemployment rate at 3.6 percent. That is a tick above where it

was pre-pandemic.

Again, what do all these statistics mean for people? It means that they can go into the job market and get the jobs, the hours, the pay that they need

in order to help make ends meet. And, in fact, if you look at total compensation, it is up 10 percent faster than inflation over the past year.

That’s both the contribution for more jobs, more hours and more wages.

But that’s the one side of the equation. I said two things are true. At the same time, families are facing elevated prices. You heard the president say

it today, whether it’s the pump, whether it’s the supermarket, whether it’s housing. That inflation is still elevated.

Now, gas prices are actually down 25 cents a gallon since that last CPI report. So we didn’t see that in yesterday’s report. And that definitely is

partly attributable to the president’s actions to release more oil from the Strategic Reserves.

But those prices are still high, even as they have come down.

AMANPOUR: So, then, again, the question, which is the most important statistic? And, I mean, is it the high record inflation? Or is it those

really good unemployment figures that you’re saying, very low, 3.6 percent?

BERNSTEIN: So, another great…

AMANPOUR: Why does one matter more to the people, apparently?

BERNSTEIN: Yes, another great question.

And the way I think of it is this. I’m an economist here at the White House, and I cannot track one variable. If all I did was report on

inflation, I would be completely misrepresenting what’s going on in the economy. And economies are complex systems. They can have multiple

headwinds and tailwinds going on at the same time, which this one does.

We have very strong demand, say, for labor, which is another way of saying lots of job openings, lots of quality job openings. At the same time, we

have constraints in our supply system, largely related to the pandemic, and some of its enduring problems that it has — that are still brought to bear

today.

And, as those two coexist, people see inflation all the time. You drive down the street, you see it at the pump. Now, by the way, one thing you

also see at the pump is that prices are down thus far in April by about 7 percent, about 25 cents a gallon. And that’s helpful. And that’s partly due

to the president’s actions regarding release of oil from the Strategic Reserves.

So, you have to — you can’t evaluate this economy on one variable, on inflation alone. You also have to look at the opportunities in the job

market, household balance sheets, lower child poverty, the fact that evictions were significantly arrested by the Rescue Plan.

And I think, if you take that full picture, it’s really important to try to think about where people would be without that strong economic backdrop

right now. We are much well-prepared to face these headwinds than what otherwise be the case.

AMANPOUR: OK, so here’s the real big question, apart from — well, the bottom line is, the president has basically framed the sanctions on Russia,

the help to Ukraine as a necessary war effort to preserve our — quote — “way of life,” to preserve democracy.

And that’s happening on the battlefield in Ukraine. Does — when we try to figure out whether he’s going to keep and you all are going to keep up this

— these tough measures against Russia, despite the pain it’s causing, do you think he’s bringing the American people along enough on that issue?

Will the political will remain to defeat, as you — as everybody says, Putin must be defeated or this plan must be defeated, his plan in Ukraine.

BERNSTEIN: The answer to that question is a firm yes.

Not only is the political will there. It is extremely strong in this president. I think you hear the passion in the words that you played at the

beginning of this segment. But it is a political will, something kind of rare these days, that crosses the aisle. It’s bipartisan. If you look at

polls, the American people broadly support, at quite high levels, these kinds of interventions, because they recognize that — and the president

has been clear about this.

We’re going to do everything we can to try to insulate households from some of the pain and pressure particularly around commodity prices, energy, we

have talked about, food from this conflict. But we cannot 100 percent insulate everyone.

There has been and will be pressures coming from that. And the American people, I think, at least if you read the polling data, seem clear that

they’re — not only do we have the political will here, but I think they have the — kind of the fairness, the spiritual will to pursue this —

these actions against the horrific facts on the ground that we’re learning about in Ukraine.

AMANPOUR: Let me just also frame that, because, again, it’s really — it really takes a strong sort of spine to continue this. Look at the situation

in France.

Marine Le Pen, the far right candidate, has gotten herself within striking distance of the French president. It’s the first time that party has done

that, and all because of cost of living issues. She’s not talked about immigration. She’s not talked about all those dog whistles, as she normally

does. It’s all about cost of living. That’s her campaign.

Are you concerned about that?

BERNSTEIN: We are certainly concerned about the challenges that households face from these budgetary pressures.

And you heard the president say that specifically in the comments you played earlier. I think the most important thing that we can do here is

twofold, one, express to the people with the passion and conviction of this president how deeply important and existential the fight in support of

Ukraine is.

And I think that he’s been extremely convincing. And the polls suggest that Americans agree with him. And, in fact, it’s even a bipartisan view here.

Secondly — secondly, to make sure that families know that we are fighting to do the best we can to insulate them from these inflationary pressures on

their household budgets.

The release of 180 million barrels of oil from the Strategic Reserves — the president, by the way, worked with partners in Europe and other

advanced economies to kick that 180 up to 240 million barrels. Yesterday, he announced a plan for cheaper gasoline, particularly in the Midwest.

And these are having an effect. The price at the pump is down about a quarter, according to AAA retail gas numbers. We see goods getting through

the port. We see our shelves amply stocked. Our actions are helping.

If we were simply saying to the American people, yes, there’s a lot of inflation out there, but there’s a conflict and let’s see what happens,

that would be a different story. That’s not at all the story we’re telling. We are dispatched from this president to relentlessly fight on behalf of

American families and their household budgets.

AMANPOUR: One of the things that motivates the American people — and it shows up in elections these days — and also the president was this

commitment to climate.

It’s a big deal in the U.S. and around the world. So, many are asking, why not use this opportunity, instead of pumping more oil and lowering prices –

– or to lower prices, which I know — I understand what you’re doing.

But, but why not take this opportunity to actually double down on the renewables and use that to sort of insulate you all for the future?

BERNSTEIN: It’s a fair question.

And the answer is that we have to do both. This is not an either/or. This is not either we pump or we go renewable. This is a both/and. This is a

walk-and-chew-gum moment. I think I have run out of metaphors. But I think you know what I mean. We have got to do both.

And the reason we have to do both is, we must make sure that we bring people along with us. You have heard and you were — you, yourself, were

citing poll numbers suggesting that these elevated prices are a stressor to family budgets. And it’s something the president talks about every time he

talks about the economy.

He remembers his own family going through those kinds of pressures, and he tells you about it. So I think that kind of empathy is well-understood by

working Americans. And we have to make sure that, as we transition to a more renewable and green economy, people understand that both of these

paths are essential.

Now, the question I think, is, do we have a robust, effective plan to get down that path, to make that transition, electric vehicles, tax credits to

support solar and wind, hydrogen? In fact, if you look at our green agenda, it’s very deep. And we continue to fight legislatively to set that path and

to both help folks at the pump today, but free ourselves from the dependence on autocratic and vicious plutocrats at the same time through

our pursuit of clean energy goals.

AMANPOUR: As you said, there’s a lot on your plate, but it’s in — the stakes are very high.

Jared Bernstein, thank you so much for joining us.

And, as we said, President Biden has accused Vladimir Putin of genocide. He later elaborated, saying, we will let the lawyers decide internationally

whether or not it qualifies.

But the United States is limited in helping the investigation, as it does not recognize the International Criminal Court.

I asked Ben Ferencz — he’s the last surviving Nuremberg trials prosecutor — if the United States should sign up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BENJAMIN FERENCZ, NUREMBERG TRIALS PROSECUTOR: Absolutely. Absolutely should be in the lead, as we were on so many things, and taking a sensible

position, instead of taking, well, do we need it? Are we going to be restrained?

Nobody likes to be restrained. All the murderers think they’re doing it in the national interest. I regret I have one — only one head to give for my

country.

To die for your country is not glorious. To live for your country is glorious. And so we have it all backwards. And I don’t know how many more

people must die before we begin to realize it.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Such passion born of such experience. At 102 years of age, Ferencz has very, very firm views on trials and accountability. And you can

see the full interview on our program this Friday.

Meantime, ITV News correspondent Dan Rivers went back to Bucha in Ukraine to investigate three brutal killings. Here’s his report, which we must warn

you contains graphic and distressing images.

And what he finds is troubling, but it’s important to see.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

DAN RIVERS, ITV NEWS REPORTER (voice-over): If there is one place in Ukraine which has come to symbolize the barbarity of this war, it is Bucha.

The images which emerged from this town gave the world its first glimpse into the terrible consequences of a conflict prosecuted without limits.

Today, the drive into Bucha looks very different to those first hours after it was liberated on the 1st of April.

This was the first evidence of the crimes perpetrated here, the bodies of civilians left decomposing where they fell. For more than six weeks, the

world’s attention has focused on the horrors unfolding in Ukraine, in particular, the town of Bucha to the west of Kyiv.

We have investigated three separate atrocities in Bucha to give a sense of the widespread, indiscriminate murder being carried out by the Russian

army. The first involves a man whose body was found at this mass grave next to St. Andrew’s Church, where investigators are beginning to uncover the

scale of the slaughter in Bucha during the nearly month-long Russian occupation.

Volodymyr Stefianko is just one of dozens of relatives looking for answers. The number of bodies buried here is unknown, but it’s thought there are at

least 115. They were horridly interred here by locals. Most were shot on the streets of Bucha.

Now each is being carefully recovered for a full forensic examination.

We’re with Volodymyr as he waits to find out if his brother Dmytro is among the dead. As the face of each is uncovered, suddenly, the awful moment of

recognition.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): Close his eyes over there, the fourth one.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): The fourth one?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): The fourth one, or which one is it?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): It was painful. I felt sorry. I wanted to hold him, to close his eyes, to talk to him. And then it was just

tears and pain. What else? Hatred towards these Russians.

RIVERS: We accompany him to the place where his brother Dmytro was killed. We find an eyewitness who was there that day and detained moments later by

the same group of half-a-dozen Russian soldiers.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): They ran that way. And then they shot him and dragged him here. And here they shot him dead.

RIVERS: Oleg’s testimony matches the physical evidence here. We find a 7.62 shell casing from an RPK machine gun on the ground where Dmytro was

executed.

Bullet holes in the fence match Oleg’s description of the shooting. Other neighbors here heard shots at around 10:30 on March the 26th, the day he

disappeared.

Oleg recognizes the photo of Dmytro and confirms he was shot dead here, adding, another man who was with Dmytro managed to escape. I asked

Volodymyr if he feels he got closer to the truth about how his brother died.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): Yes. Yes. I have got everything. I am just wondering, when that guy ran away, did my brother ask for help or

just lie there thinking, what will be will be?

RIVERS: Dmytro’s murder was just one of possibly hundreds of similar summary executions. But a mile north of the place he died is a children’s

camp where there’s evidence of more organized killing.

What you’re about to see is a video recorded by the Ukrainian authorities after they first entered the basement of the building used by the Russians.

Their hands bound, they appear to have been shot as they knelt on the floor.

While the Russian government has accused Ukraine of faking massacres like this, we found several pieces of evidence pointing to Russian

responsibility. The children’s camp was marked with a V, a symbol used by Russian forces to identify themselves. Russian ration packs litter the

entrance to the cellar.

But, inside, there are more clues.

(on camera): You can see the bullet marks still in the wall here. The angle that the bullets came in is coming down, suggesting the person was

standing over there and the victims were down here. There is actually a bullet down, here which is a .545-caliber Kalashnikov bullet with a steel

core, which is only issued to the military.

(voice-over): We were given access to this seller because forensic teams have concluded their work. The identities of the men found here have now

been established.

They were Sergei Miteshko, Volodymyr Pachenko, Victor Plutko, Valerie Plutko, and Dmytro Shulmeister.

Dmytro’s sister says he and four others refuse to flee, deciding to help others to escape Bucha until the Russians caught them.

TATIANA SHULMEISTER, SISTER OF VICTIM (through translator): He lived a normal life. He was in his own house, on his own land. These animals,

barbarians showed up and took his life away. Why? What for?

RIVERS: Two miles south of the children’s camp is the site of another massacre, this time even larger. Outside an agricultural construction

agency, the bodies of eight men were found near the steps to the side of the building. Three more were found elsewhere on the site.

This is the scene which investigators found. This man had his hands bound behind his back and his fingernails removed. One has electrical cable tied

around his feet and has been beaten across the back. A military crate with the markings of the 7th Paratroop Unit was found close by. Inside the

building was another body on a stairwell.

(on camera): This is where some of the most harrowing images to emerge from Bucha were taken. The police have found eight bodies here and more

inside. They don’t know how many people were killed here in total. Forensic officers are continuing to comb this building for clues.

But it appears this was some sort of torture center.

ANTON ONOPRIENKO, UKRAINIAN STATE SECURITY AGENT (through translator): It was one of their headquarters, but they also executed people right here.

They also used the place for filtration activities.

RIVERS (voice-over): By filtration activities, he means selecting which prisoners would be executed.

We have identified one of the dead men found here as Anatoly Prohiko, who was born in 1983 and may have been targeted because he was with Ukraine’s

territorial defense. A witness who saw his body told us his cheek had been cut out, there were multiple stab wounds on his torso, and he’d been shot

through the chest.

PETRO NEVIRETS, KYIV PROSECUTOR’S OFFICE (through translator): As for the people executed here, most of them had their hands bound. That is a sign of

torture.

RIVERS: One man has spoken to us who saw, heard and survived the massacre.

Speaking for the first time, but still too scared to show his identity, he says Russian soldiers were going house to house rounding up civilians to

decide who to execute. He was only spared because he could prove he’d fought in Afghanistan as a Soviet soldier 40 years ago.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): I saw the guy who was shot in his back, and, after him, another two guys. I was put in another group with

some other people.

Then they took 10 to 12 people they had separated from the crowd and put their T-shirt over their heads. Their hands were tied behind their backs,

and took this group around the corner of the building. And then the soldiers came back alone. I heard shooting. And then the soldiers came

back, and all those people were killed.

RIVERS: As the war crimes investigation starts, there are, of course, questions about whether these three cases were part of a wider campaign of

orchestrated murder directed by senior leaders in Russia, something I put to Ukraine’s prosecutor general.

(on camera): Was this orchestrated? Or was this from just rogue units of the Russians?

IRYNA VENEDIKTOVA, UKRAINIAN PROSECUTOR GENERAL: Of course, it was order to kill civilians because we see gunshots. That’s why it’s actually — it

was order.

And what you see here in Bucha and other small cities, small villages which were occupied in Kyiv region, actually, you see it’s not only war crimes.

It’s crimes against humanity.

RIVERS: To what extent does President Putin hold responsibility for this?

VENEDIKTOVA: President Putin is a main war criminal of 21st century. Of course, he is responsible of all of this, what is going on now in Ukraine.

But you remember that it was in Chechnya. And what is after Chechnya? It was in Georgia. It was in Syria. And he still not responsible for all these

crimes against humanity. That’s why we should do everything to punish responsible — people who are responsible for this.

RIVERS (voice-over): The service to remember the victims of Bucha at St. Andrew’s Church involves a choir now a quarter of the size it used to be.

One has died. The others have fled. But the Russian occupation hasn’t silenced those who remain.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE (through translator): Forgiving those who before your eyes raped your children is very difficult. And this is road is long. This

road is difficult.

RIVERS: But while survivors search their souls for the strength to forgive, Bucha will never forget what happened here. And neither should we.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: ITV’s Dan Rivers. Important reporting there.

President Putin keeps calling all of this fake. And yet the chancellor of Austria, the first head of state to visit Putin since the war, went to tell

him exactly what was going on. And yet he kept, Putin, saying that it was fake.

Now to the extraordinary story of one of America’s great civil rights activists, but you probably don’t know much about him, for he has a secret

that kept him very low profile. Walter White was mixed race, but he passed as a white man, which enabled his investigative work.

Now journalist and author A.J. Baime is telling his story in “White Lies: The Double Life of Walter F. White and America’s Darkest Secret.”

He’s joining me from Sacramento, California.

Welcome to the program. It is an extraordinary story.

So, we just have to ask you to lay out for us and for our viewers who haven’t read the book or know about him, what is it that allowed him to do

so much important work, and yet, and yet not be known?

A.J. BAIME, AUTHOR, “WHITE LIES”: Well, the subtitle of the book is called ‘The Double Life of Walter White.”

So, Walter described himself, Walter White, as the enigma of a black man occupying a white body. So, he was born into a black family. His parents

were among the last who could remember from memory being born into slavery. But Walter had white skin, blond hair and blue eyes. And he lived a double

life, his entire life, in the service of civil rights.

So he could live as a white man. He could live as a black man. He identified as black. And sort of weaponizing his skin color, if you will,

he was able to come wash some amazing things.

Now, at the end of Walter White’s life he had a scandal, a controversy that sort of destroyed his reputation and that’s why nobody knows who he is

today.

AMANPOUR: So, we’ll get to that in a second. But recount for us, A.J. Blaime, what he actually did. He was formative in the NCC — NAACP, but he

went out to these places and investigated. What did he do and how was he able to get to places?

BAIME: In the first half of this book, it really explores Walter White’s life living as an undercover white investigator. So, starting in 1918 when

he began work with the NAACP, he — actually, it was his 12th day. He read about a murder and torture of a black man in front of 1,500 people in the

tiny town of Estill Springs, Tennessee. And Walter had this idea that he could go down — he was a black man. He identified as black. But he knew

that he could go down there and pose as a white man. And this was the — and get the facts. And so, he became a crimefighter.

This was the first of over 40 investigations, undercover living as a white man in the South that Walter White conducted from 1918 to 1930. And these

were some of the most harrowing crimes in American history that made sensational headlines and made a star out of Walter White.

AMANPOUR: And what about the NAACP? You know, when he came along, it was really a fledgling organization.

BAIME: That’s correct. So, he was plucked obscured — out of obscurity by James Weldon Johnson of the NAACP. James Weldon Johnson is a fascinating

figure and really became a mentor to Walter White. So, at that time the NAACP, nobody had heard of it. If they had, it was probably because the

NAACP employed the two greatest black intellectuals of the era, that would be James Weldon Johnson and W.E.B. Du Bois.

Walter comes on the scene in 1918 and begins to really earn a name for himself through these undercover investigations. And frankly, I think,

that’s a good reason why we know of the NAACP today because of these investigations created massive wellsprings of support for the NAACP, huge

amounts of publicity. And by the time Walter White became chief executive of the NAACP in 1930, it was the largest, most militant civil rights

organization that had ever existed.

AMANPOUR: Let me just focus on some of the things that he was transformative in changing. You mentioned his brave, you know, undercover

investigation as a white-skin black man including to investigate in Tulsa in 1921, the massacre there, the lynching. And then recently, President

Biden had signed a bill named for Emmett Till and Vice President Harris said lynching haven’t been confined to history. This is what she said.

Let’s just play it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

KAMALA HARRIS, U.S. VICE PRESIDENT: Lynching is not a relic of the past. Racial acts of terror still occur in our nation. And when they do, we must

all have the courage to name them and hold the perpetrators to account.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you know, we’re in the midst of — and we’ve just been reporting, obviously, about crimes and accountability. And this idea of

accountability is so front and center now with the war in Ukraine and the horrors that Russia’s committing. And I just wanted to know how Walter

White influenced the leaders of his time to come onboard with these, whether it’s FDR, Harry Truman?

BAIME: Well, there’s two ways to answer that question. For starters, Walter White conducted, as I said, over 40 undercover investigations posing

as a white man — these horrific murders, he was able to find out who the perpetrators were, publicize their names, write memorandums about these

crimes to the governors of the States and the attorney general and the President of the United States, ad no one was ever arrested for any of

them.

And so, Walter White and NAACP went on this maniacal quest throughout the ’20s and ’30s to create a federal anti-lynching law. So, if somebody was

murdered in a small town in Tennessee and nothing was done about it even though everybody knew who the killers were, the federal government could

step in. And they fought for generations and decades and never really realized victory in that fight. And that’s why the recent federal anti-

lynching law signed by Biden is such a momentous occasion.

The other way to answer your question is, you know, half way through the book, “White Lies,” Walter realizes that his undercover work, his

investigations, and his — the articles he was writing in national magazines was only doing so much. It was making NAACP famous. But he

realized that racism was really systemic. And they didn’t use that word at the time. But the second half of the book is really about his life in

national politics and becoming a political powerhouse. Because he realized the only way to effect change, to bring, you know, democracy for real to

not just white Americans but black Americans was voting power and the oval office.

AMANPOUR: And then tragically, I don’t know whether you agree that it’s tragic but it seems to be that he divorced his wife, who was black, and he

had been in love for a lot — a number of years with a white woman who he eventually married. And that just caused a scandal that obliterated his

contribution and his historic position in American society.

BAIME: That’s absolutely correct. I think when people will read the book, you will agree with me that I don’t think there’s any doubt that Walter

Francis White was the most influential civil rights leader of the 20 — first half of the 20th century. And you’re saying, how can that be true?

Nobody’s ever heard of him and there are really two reasons.

One is, at the end of his life he endured the shocking scandal because he identified as a black man. He really was the face of black power in

America. Very ironic given the fact that he had blond hair and blue eyes. But he identified him as black. He had — he was born into a black family.

Late in life, he ended up leaving his black wife for a white woman. And the scandal was just apocalyptic in his life. And this happened shortly before

his death. And I think that he had been conducting this affair secretly, trying to keep it a secret because he knew what it would do to his

reputation, and it did destroy him.

The other reason why people don’t know about him today because right when he died, Martin Luther King Jr. comes on the scene, Montgomery Bus Boycott,

the new generation of civil rights leader really — they weren’t interested in having a man with white skin and blue eyes be the face of their

movement. Specially in the new age of television. So, Walter White’s legacy quickly disappeared.

AMANPOUR: It’s really a remarkable story. A.J. Baime, thank you for bringing it us to. “White Lies,” it’s really an incredible story. Thank a

lot.

Now, the Ukrainian president, today, addressed his 26th foreign government since the war began, that was Estonia. And “The Economist” editor in chief,

Zanny Minton Beddoes, recently met Zelenskyy to discuss the world’s response to Putin’s war. Now, back from Kyiv, she spoke to Walter Isaacson

about it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, HOST: Thank you, Christiane. And Zanny Minton Beddoes, welcome back to the show.

ZANNY MINTON BEDDOES, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, “THE ECONOMIST”: Thanks for having me.

ISAACSON: You had an amazing interview with President Zelenskyy. You went to Kyiv. He said some amazing things with “The Economist”. But first of

all, tell me, what it was like to get there? What was it like to go to his office? How did you get there?

BEDDOES: Well, I go to Kyiv. I flew to Warsaw, then took a car to the border and across the border to Lviv, that city in Western Ukraine where

all of the refugees are coming through, and then took the overnight train from Kyiv — from Lviv to Kyiv which was quite an experience. And actually,

the first time, Walter, that I really felt that I was in a country at war was at Lviv station where we arrived late at night. The lights were dim. It

was full of people. Full of — absolutely full of people. Soldiers — but also huge numbers of refugees.

Tired. We went past the anti-tank, traps, the barriers, through — up to a big metal gate, then we had to leave all of our — of course, all of our

pens, phones, everything behind so that nothing that could possibly give away the location. Up, down corridors, and then eventually we ended up in a

room that you would have recognized, which is the room from which President Zelenskyy addresses, you know, parliaments around the world. It looks a

little, actually, like a corporate meeting when you’re there with a big formica white table and office chairs.

While we were waiting there and then suddenly there was a little kerfuffle and some men with guys came and he walked. And we spent over an hour with

him. And it was the most — probably the most extraordinary interview I’ve ever done. He is — he’s extraordinarily authentic person. You know, of

course, he was an actor and he — but he– you can’t — I don’t think, keep up an act for more than an hour. He had no notes. He spoke in three

languages, for my benefit. My — you know, he spoke in English a lot but then also in Russian and Ukrainian. One of my colleagues both fluent in

Russian. And he was very, very genuine and authentic. And it was just — one of those times u come across someone who is absolutely the right man

for the moment, and I really felt that.

ISAACSON: You’ve interviewed world leaders throughout your career. Does anybody come to mind like that or even in history like a Churchill?

BEDDOES: Well, you know, the interesting thing is that people compare him to Churchill. And that he is a modern-day Churchill. And I — at the end of

the interview, I said to him, you know, you’re often compared to Churchill, President Zelenskyy. And you know, used to practice his speeches a lot. He

was — he took his artry very seriously. And I said, do practice your speeches? And he looked, as though I was kind of crazy and he said, no. I

don’t have time to do that.

I just feel it. And it was actually, sort of, rather telling insight into how he is. I mean, I — he — of course, he has speech writers, I’m sure

very good speech writers. But he really does seem to be feeling that.

And he is channeling the sense of Ukraine. It’s — you know, he’s a kind of an everyman, and you know the story, right? The everyman, the actor who

became president kind of almost by accident. And now, he is channeling that spirit of fierce resistance, the bravery, you know, his unwillingness to

leave the capital when the invasion started. I asked him about that and he said, the protocol had been that he ought to leave but he refused to leave

because he said it was very important that he be there in Kyiv.

And he’s clearly an immensely brave man. But he’s channeling and is the sort of avatar for the entire Ukrainian people right now. And that comes

through very, very clearly.

ISAACSON: You just referred to him as brave, but I remember he pushed back on you in the interview when you called him brave.

BEDDOES: That’s right. He said — I mean, you’ve obviously watched the interview. He said, I’m not so brave, but maybe I understand, he said. And

he was — he came across as very humble and he wasn’t — there no kind of braggadocio, no, I’m the hero. He was very much just channeling what he

felt he had to do. And as such, he was standing for, you know, all of the 44 million Ukrainians. He was the everyman who had been put into this

situation and was now, you know, channeling and standing up to Vladimir Putin.

And the other part which — of the interview which really struck me was when I asked him about Vladimir Putin. And I said, could there be a lasting

peace with Putin and the Kremlin? And he paused, he paused for what seemed like a very long time, I think it was five or six seconds, and he said, I

don’t know. And then he said, I don’t think he knows. And he went on to describe later in the conversation, Putin, and it was clear to me that he

finds Putin’s cruelty and callousness literally almost incomprehensible.

And he said, you know, they have lost 15,000 Russian soldiers. He says, Putin treats Russian soldiers like logs thrown into a train’s furnace. And

as he said that to me, it was very clear from the impression — it was very clear from his face that he just couldn’t comprehend that kind of lack of

humanity.

ISAACSON: He said something that really surprised me when you asked the question of what a Ukrainian victory would look like, and he said, victory

is being able to save as many lives as possible. And to me, that was surprising. My head snapped because he’s not saying, victory would be we

would protect all the territory of Ukraine, it seems almost he’s willing to sacrifice some territory, that his primary goal is to save lives. Is that

right?

BEDDOES: Well, he did then — that’s — he did — you’re absolutely right. That’s what he started with. And then, he went on in the answer to say

that, we will fight until the last city, I’m paraphrasing. So, he does care about territory. But you’re right, his first answer was in terms of lives

and he clearly cares about lives.

He wasn’t giving away to me what his bottom line would be in any peace agreement. And I think as Ukraine has made strides militarily so there is a

sort of — there is greater optimism and sense that the peace will be on Ukrainian terms. But you are absolutely right, that for him this is about

lives, this is about Ukrainian’s dignity, Ukraine’s agency, Ukraine’ freedom.

ISAACSON: The Economist today comes out with amazing leader, an editorial that says that this war is not just being fought for Ukraine, but for the

principal that all countries are sovereign. And you say, it’s a fundamental argument for how the world should work. And then, there’s a sentence that

just knocked me back. You said, this is an argument the West is losing. Most of the emerging world either backs Russia or is neutral. That is a

stunning rebuke. It’s also taking the world down a dangerous path. Why is this happening?

BEDDOES: So, that’s exactly what we were trying to look at in this week’s editorial and with a big accompanying piece. And I think there are a number

of factors. One is that I think there are many countries in the emerging world that think the West has double standards. They remember the hubris of

the invasion of Iraq and they think, well, that didn’t have U.N. support and the West thinks that that’s fine. But now, when there’s another

invasion, you know, what is so different about that?

They think there are double standards in, you know, the way the West treats refugees. A huge amount of focus on Ukrainian refugees but they remember

when Syrian refugees came, the Europeans were much less welcoming. They also see double standards in things like climate change. You know, the West

which caused a lot of the problems of climate change, they now think that the West is expecting other countries in the world to, you know, sort out

the problem that they created.

So, I think there’s a sense in much of the world that the West is — you know, has double standards. It’s somewhat decadent, has been kind of

focused on itself, has let the rest of the world down. And there’s also, of course, some self-interest, you know, with rising fuel prices, countries

are — you know, want to maintain access to Russian fuel and particularly important countries like India, you know, they rely on — get a lot of

weaponry from Russia. Russia, they play, you know, an important role in India’s position, vis-a-vis China.

So, I think there’s a sense that the West has been both decadent, self- serving, had double standards. And some of that — frankly, some of that is — there is a bit of truth to it. I think it is exaggerated but there is

somewhat —

ISAACSON: Well, wait. Tell me what the truth — you think the truth —

BEDDOES: If you look at — say what happened in Afghanistan last year, where the United States, you know — and whatever you think about the

merits of leaving, the manner in which the United States left, left a lot to be desired. And so, I think —

ISAACSON: But do you think what happened in Afghanistan’s withdrawal is the reason that countries like India are not supporting our efforts in

Ukraine?

BEDDOES: No. I think there is a sense — I think it is weighed into the sense that the West’s, you know, toxifying game in terms of, you know,

sovereignty, universal values, human rights but actually is fairly kind of elastic in what it stands up for, which — what — how far it is willing to

go.

I’m not — I’m absolutely not suggesting, you know, all of this is justified, and that’s why we wrote our editorial. But the point that we

wanted to make was to say that, even if there is something to some of these criticisms, even if the West has fallen short, the alternative world that

Russia and China, like particularly Russia in this case are, you know, showing us, which is a world where might makes right, where it’s OK to kind

of invade another country where sovereignty doesn’t matter, every country in the world, particularly emerging countries, are worse off in that world.

And so, even if you think the West has not been as, you know, powerfully standing for the principles that it espouses, that it could be, you are

still better off in a western led, you know, the rules-based system of the sort that we build up since 1945. And that is really, I think, you know,

being tested right now. And that’s why it’s important and that’s why it’s, quite frankly, deeply worrying that so many countries are sitting on the

fence.

The point of our editorial was to argue that it is in country’s self- interest to get off the fence. What Russia is doing in Ukraine is not the kind of world that any county should want to live in.

ISAACSON: One of the other surprising things is Saudi Arabia not being helpful here. Saudi Arabia not starting to pump more oil when we’re faced

with an oil crisis. You’ve been there a couple of times. You even drove a car in Saudi Arabia when they first let women drive. Why is it our

relationships, meaning the relationships between the West and Saudi Arabia have deteriorated so badly and how do we fix that?

BEDDOES: So, I think there is a — the main reason is that Saudi Arabia and many other countries in the Gulf see, I think, Iran as the biggest

threat and think that the U.S. has been less than helpful in sort of dealing with that threat. And again — so, that’s one important reason.

The other is, I think, that the Saudis feel that the Biden administration, in particular, treated them as a pariah state, was pushed — you know, was

less than open and friendly. And so, that kind of — you know, I’m going to paraphrase, but now, you know, you want us to help you when it suits you,

but you’re tough on us when it suits you, too. And that, I think, is very much the view in many of the Gulf states. And I think that’s also —

ISAACSON: Well, isn’t there an odious smell of truth to that feeling?

BEDDOES: Yes. There is a bit of truth to that. That’s why I said earlier, there is some truth to many of these criticisms of hypocrisy, double

standards that you hear in the emerging world. The West has been, you know, less than living up to the ideals that it espouses. But nonetheless, the

world would be worse off in the world of the sort that Russia is now exemplifying by invading Ukraine.

ISAACSON: You know, we are in a war for the soul of the international order and we also have a food crisis, we also have an inflation crisis, we

have a refugee crisis, we have an energy crisis going on, and all of this is coming together into a perfect storm. As somebody who has watched

history, how do you assess this moment in history?

BEDDOES: Well, I think you’re right in pointing to all of those as being very serious challenges. I think collectively this is one of the most

challenging geopolitical and indeed, economic times we’ve ever faced. Certainly, in my lifetime.

And we’ve been through some. You know, we’ve had the financial crisis, we had a number of other very challenging episodes. But right now, if we put

together this war in Europe and its ripple effects, which are already soaring energy prices, soaring food prices, and I think much, much big

eruptions, politically globally thanks to soaring food prices, we are in for a very rough time because it is, as you say, against the backdrop of

this very big challenge that is comes from a rise in China to our western- led system. It is being tested.

But, you know, Walter, one of the things that gives me optimism now, and I’ve had that, you know, reinforced really dramatically when I was in Kyiv,

seeing the Ukrainian people come together, seeing the determination with which they are willing to fight for freedom, the kind of things that you

and I take for granted, the determination they have to repel this aggressive invasion by Russia.

When you hear that Poland has taken more than 2 million Ukrainian refugees, they are staying in people’s houses, they are going to local schools, they

are squashing in, that gives you, I think — it gives me hope that we are willing to stand up for the western principles. And so, there is, I think,

a moment of optimism amidst these incredible challenges that you laid out.

ISAACSON: And this moment of optimism, does it extend to the rest of the western world? Do you think this is going to inspire a renewed belief in

democracy and world order and strength among the West or do you worry that, say the French elections show that it’s a close call?

BEDDOES: Both of those. I worry a lot. I worry about the French election. I worry about the U.S., frankly, what’s going to happen later this year,

what’s going to happen in 2024. But at the same time, you know, I hope that the optimism that I felt in Ukraine is one that can sustain and last and

that we will prove able to, you know, withstand and overcome these challenges.

Because, look, I’m an English classic liberal to my core. That’s — you know, that’s where I spend my career at The Economist. I believe in

individual freedom, free markets, open societies. And I think that, you’re right, they are being tested right now, but it is a test that I fervently

hope that we succeed.

ISAACSON: There is a backlash against that sort of form of old-fashioned liberal order, a backlash against free trade, free immigration, individual

liberty. We see it with Viktor Orban in Hungary winning so well, we see it with Marine Le Pen coming up as a strong challenger in France in the coming

weeks. What is causing this populist authoritarian backlash?

BEDDOES: So, there are a lot of reasons. There are — right now, cost of living is a large part of it. People are feeling that their living status

are being eroded. The rapid pace of technological change. People feel the world is changing and that, you know, in many countries, majorities of

people feel their children will be worse off than they were. That’s a very, very corrosive environment.

And so, we’re in the midst — and, Walter, you’ve written about this. We’re in the midst of, you know, dramatic technological change, we’re in the

midst of dramatic social change. People feel worried. They feel nervous. They feel that the world has been unequal. Too many of the benefits have

gone to the very healthy. You know, globalization is now a dirty word. It’s called globalism and it’s a pejorative word. And I understand that. I think

there’s some truth to it. And people who believe in the benefits of, you know, open societies and free marks, it’s incumbent on them to, you know,

provide the kind of policy framework which ensures that people don’t get left behind.

Better education, better tax system, greater equality, all of the things that, you know, people perhaps have ignored or haven’t paid enough

attention to. But nonetheless, I think, you know, no one suggests that where we are right now is the perfect world. There are plenty of things

that need improving. But what I’m very clear about is that a world where you don’t have freedom, you don’t have open markets, you don’t have

individual freedoms is a much worse world.

ISAACSON: Zanny Minton Beddoes, thank you so much for being with us.

BEDDOES: Thank you for having me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And that’s it for now. Remember, you can always catch us online, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Thank you for watching and good-bye from

London.