Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, as violent crime surges in the United States, the ongoing struggle between American law enforcement and the public remains in the spotlight. Justin Fenton chronicles the rise and fall of one Baltimore Police Department Task Force, that’s in his book “We Own This City.” And he is joining Michel Martin to discuss crime, cops and corruption.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Christiane. Justin Fenton, thank you very much for talking with us.

JUSTIN FENTON, AUTHOR, “WE OWN THIS CITY”: Thank you so much for having me.

MARTIN: I’m guessing that if most people think about a scandal involving the police in Baltimore, they would think Freddie Gray because, of course, you know, in April of 2015, this young man was apprehended by the police under sort of — for dubious reasons, he was, you know, put in the back of a police van and later died a week later and his death set off, you know, days of unrest, of violence, of rioting, of looting. But all of this was happening while a bigger story, I could argue, was taking place, one that I bet you outside of maybe the immediate area most people don’t know anything about. We’re talking about the story that you write about in your book, “We Own This City,” about the gun trace task force. How did it start?

FENTON: Really, it probably starts decades ago. I think one of the things this scandal has really underscore is it this behavior by police, and when we’re talking about lying on official documents and conducting searches without warrants, stealing money, stealing drugs, this scandal revealed that this has been going on for decades here. And we continue to find out new revelations to this day. Just the last month there is a veteran sergeant who took the stand in a trial and outlined 20 years’ worth of stealing and lying and it had become systemic here. And it was exposed not through the fallout of the Freddie Gray case or the civil rights investigation by the Justice Department that followed, but by suburban drug investigators who sort of fell backwards into it. It’s a pretty interesting tale how it all unspooled.

MARTIN: So, give us the parameters of this. These were a group of cops supposedly in this elite unit tasked with getting guns and drugs off the street, but in fact, they were robbing people of cash and drugs and even selling drugs themselves.

FENTON: Yes.

MARTIN: And while famously, none of the police officers involved in the Freddie Gray case were convicted, in fact, eight members of this particular group all went to federal prison. So, how bad was it? Like, what is the scope of this conspiracy? How much money? How many people? How many drugs?

FENTON: The scope of the conspiracy is just as you said. Officers who just on a regular basis sort of built into the way they did their jobs were not being watched, not being held accountable, not being investigated. When complaints came in, those complaints were being discarded, they weren’t believed. In Baltimore and every other city, I would say, these plain-clothes units, and I want to explain what that is briefly. You know, we think about, you know, undercover officers who might assume a different identity. This isn’t what that is. These are officers who go out wearing hooded sweatshirts, jeans, a police vest and they drive around in unmarked cars. These officers are sent out by the police department to try to find crime to try to find crime, to try detect who might be carrying a gun, who might have drugs, and they were, for years, given this leeway to work in a gray area — really not a gray area at all, because they’re breaking the law, but that’s the way the department saw it, is that they were giving them this deference because they were asking them to find this crime, and these officers were taking advantage of the deference.

MARTIN: They have different names for this kind of policing in different cities. I think in New York many people know what a stop and frisk. In D.C., they call these jump out boys.

FENTON: Yes.

MARTIN: In Baltimore, what are they called?

FENTON: In Baltimore, they also call them jump out boys as well as knockers. As far as these knockers with the connotation being — you know, beating people up, being rough with people. And yes, their trademark was to sort of drive up on corners, if there was a quick gathering of young black men in a — in what’s considered a high-crime area, they would drive up and jump out of the car. One of the tactics that was revealed by the officers who cooperated, one of the tactics they described was called door pops, where they would drive up really fast, slam on the brakes and pop their doors. And if people started to run, they thought, OK. Well, that guy must have something. We’re going to chase after them. So, they were sort of trying to coerce people into this stuff.

MARTIN: You could imagine where some people might say, well, you know, so what? I mean, these people are probably doing something bad and if they’re trying to sort of interrupt it, intervene, you know, what’s so terrible? What’s the harm?

FENTON: Yes. So, I mean, what we often see with these kinds of traffic stops and these kinds of things is when they are successful. When the police pull somebody over for not signaling, they smell marijuana, they a sort (ph) of movement and they search the car and they find a gun, and that’s considered a success. The gun is, you know, displayed on social media or at a press conference and we look at how the police successfully detected crime. What I really got into with my reporting for this book was looking at all of the times they stopped people when they did not find a gun, and that revealed lots of stops where people were pulling off of a gas station parking lot without a seat belt on, someone sitting in their car eating lunch. A lot of stops where they went up to someone with no good reason, did not find anything and you don’t hear about them. So, you might hear about them with people grumbling on the street or people speaking at a community forum, but those were the kinds of things that went on. That the police described it as a numbers game. The more people they could stop in a night, the more likely they were. And to get those numbers, they were not following the rules. And I think to your first point about the fact that a lot of people that were violated here, were engaged in crime, that’s absolutely true. That’s a large reason why it was not detected earlier. They would come across somebody with six kilograms of drugs, they would turn in five and steal the sixth one. That’s not in anyone’s best interest, when they’re stopped with six kilograms of drugs, but the cops turn in five to say, actually I had more. Or if you have drug money, you know, $200,000. They’d turn in $100,000. You know, how can you account for that money? Who is going to believe you? Why would you admit to having that? So, they definitely, definitely took advantage of that to get away with this.

MARTIN: When this group of cops was arrested, they found BB guns in their cars. Why did they have BB guns in their cars? That’s not an authorized issue — you know, service revolver. Why did they have BB guns in their cars?

FENTON: Yes. The BB guns were being carried around in case they needed them to get out of a jam. There was one incident in particular in 2014 where we know that Sergeant Wayne Jenkins who would go onto become the leader of the gun trace task force, he was chasing somebody. The person was fleeing. So, he knew we onto something. He ended up running over the guy with his car. The man’s name was Dmitri Simon (ph). He ran him over with his car. But when he searched him, he didn’t find anything. He didn’t find any guns. He didn’t find any drugs. And all of a sudden, he’s in a panic because he’s run over somebody, he’s chased somebody who he had no basis for chasing. And so, he made a phone call and they dropped a BB gun on the scene and this was described by officers as something that was used as sort of a cautionary tale to have a BB gun on you in case you get into such a jam. And when you plant it, if you put it on the scene it would help to justify your actions and people will say, well, you know, he ran him over, but, look, there was a gun found. And these BB guns can look very realistic. You know, they’re toy, but they look like real guns and they’re often used in the city to carry out real robberies.

MARTIN: Do you hear what you’re saying here? I mean, you’ve been reporting on this for years. So, you’re, like, yes, they carry BB guns around to plant on people. But do you hear what you’re saying here? And not only that, skimming drugs off of known drug dealers so that they could then sell them. I’m guessing that maybe after the HBO show, which has been developed from your source material airs people will be aware of it. But I’m guessing most people have no idea that this went on.

FENTON: Yes. I mean, to hear the revelations as they came out during the trial with the officers taking a stand one by one and explaining these things, it was very — it was jaw dropping. You know, again, especially in the context of the fact that this was happening post-Freddie Gray, post — you know, when the Justice Department is conducting a civil rights investigation of this department. You know, the Justice Department is here. They are supposedly going on ride alongs and checking files that the public otherwise doesn’t have access to. They’re reviewing reports and all of these kinds of things, and this was happening while they were here. They were completely undeterred. They were completely unconcerned about being caught.

MARTIN: Tell me about Sergeant Jenkins, Wayne Jenkins, who is currently serving in federal prison who was really the center of all of this. Can you tell me about him?

FENTON: Yes. Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, you know, is a white officer. He grew up in outside of Baltimore, in Eastern Baltimore County. Went to the marines and then joined Baltimore Police Department. I focused on him in the book because, first of all, it just made perfect sense. He joins the department in 2003 when the department is engaged in, you know, “zero- tolerance policing,” making a lot of arrests. The idea of being the more arrests you make the more you will pressure the community into not, you know, committing crimes or violations. So, he comes into a department that is steeped in that, and he becomes a part of that. He makes, you know, hundreds of arrests per year. And as the department shifts into using — utilizing more plain-clothes units, as I described earlier, you know, he becomes a part of that, as well. And Jenkins was viewed within the department as a hard charger. You know, some people described him as a cowboy but they also thought he was really good at his job. They thought he was really good at getting guns, get an eye for it. And that was an image that he very much carefully cultivated. As I looked through his e-mails, I requested e-mails from the police department and I saw how he regularly made sure that everyone in the department, not just his bosses, not just his peers, but everybody got a mass e-mail every time Sergeant Jenkins’ squad got a gun off the street. And he make — he would ask special favors directly from police department leadership. He received awards for his conduct. And at the same time, there were plenty of red flags. There’s plenty of things that were going on that should have caused people to take a closer look at him. His cases were being discarded at an incredible rate.

MARTIN: One of the points you make in the book is that short, yes, he had all of these arrests, but 40 percent of his cases were actually thrown out, which is higher than the average. That should have raised a red flag. The fact that he was constantly cheating on overtime. The fact that he put in for overtime while he was on vacation. Nobody noticed?

FENTON: Yes. You know, the police department operates in silos. There’s an operation side, which is every day there’s a new fight, there’s been a shooting, there’s something that they need to respond to and they deploy their troops into these combat zones. And on the other side is the internal affairs and personnel, and those hands were not talking to each other. You know, internal affairs is failing to develop cases. Whereas the people on the operations side was saying, hey, if you’re not going to find him guilty, then we’re not going to pull him off the street. If you can’t substantiate the case, you know, we’re going to keep sending him out there. Now, there is officers like Daniel Herschel who absolutely was on full blast. I mean, he’d been written about in the newspaper multiple times. He’s been a subject of a frontpage investigation by my colleague at the Sun, Mark Fuente (ph), in 2014 about repeated lawsuits, repeated claims of abuse, nothing was done about it.

MARTIN: Why did they do it? I mean, we have this idea that people — you know, nobody starts a job like that wanting to be dirty, you know. That somehow it gets good to them, right? But why? Did you ever figure out why? Why did they do it?

FENTON: I think it was easy money. I think that — you know, again, we send officers into somebody’s home and we tell them, you know, if you find money that you suspect to be drug money, count it up and submit it. And if half of that ends up in evidence control, nobody is either (ph) wiser. I think as far the overtime, same thing, the department made it available. They weren’t scrutinizing it. It was easy money.

MARTIN: Is it a Baltimore problem or is it a bigger problem than that?

FENTON: I think much of Baltimore’s problems are similar to other American cities, they’re just sort of on steroids. Everything is a little — everything is worse here. Our challenges with poverty and drug addiction and crime are just, you know, exponentially worse but there are also microcosms of what I believe is happening in every city. And just like this scandal didn’t get the attention, I think, it deserved when it broke, there were similar scandals in Philadelphia and Detroit, you know, sort of — I think a new wave of discoveries of officers behaving this way, and I think it can be happening in any other city where, you know, officials are very focused on driving down crime, using police to do that and not holding them accountable.

MARTIN: Do these tactics drive down crime?

FENTON: If you listen to police officers who really believe in the work, they can articulate how clearing a corner, you know, in a high-crime neighborhood is a good thing. It keeps people safe. They’re not going to get shot that night. But it also presumes that there is going to be a shooting. There really is this collateral damage about people who have these horrible negative encounters, minor encounters of escalating the deadly force, the things that are just really not necessary, and in many ways may cost more problems than they solve. And so, we see a complete reversal right now in Baltimore, from that zero-tolerance time period where our city of about 600,000 people had 110,000 arrests in one year. Last year there were less than 10,000 arrests in Baltimore. The drug war in Baltimore, drug arrests are down some 92 percent from the peak 17 years ago. There was about three people being arrested per day in Baltimore for drugs. Meanwhile, the 911 is ringing off the hook from residents in these neighborhoods calling for police, asking them to do something about open- air drug dealing. So, I think — And meanwhile, just to put a final point on that, our crime rate is about the same. We’re still experiencing 300 homicides a year. A very high rate of robberies. But even with the 90,000 fewer arrests, it’s about the same. So, it’s a huge question of what do we want police to be. What are police capable of? What do we want them to be and what other resources need to be brought to bear to really fix some of these problems?

MARTIN: How does any of this gets fixed? It seems like such sort of toxic circle?

FENTON: Yes. I mean, I say this hoping that I’m not being naive. But I think things are getting better. You know, we are into this federal consent decree where the federal government and the judge are sort of overseeing reforms, and a lot is happening. There’s been a complete overhaul of like all the department’s policies, ranging from use of force stops and searches. And there are — there’s a team I just watched last night, that the client’s team had a community meeting where they were going — said they’d been reviewing 550 uses of force and they’re reviewing not just the officer’s conduct, but how supervisors handled it, how it was investigated. They’re taking note of the fact that supervisors are now — they seem to not just be signing off on these things but actually sending the reports back with notes. They seem to be more invested in it. So, I still think though to a certain extent a lot of officers feel as though they are not able to keep the city safe the way that they feel like they should be able to. And that’s just, again, something that we’re trying to feel our way through. It’s true. People don’t want to be harassed, they don’t want to be pulled over for minor violations and end up on the curb having their car stopped. They don’t want to get beaten up. They don’t want these things to happen. And so, you know, you can’t do that, but the department is trying to educate people on what officers can do and I think it’s an interesting moment in the city’s history and policing in general, really.

MARTIN: Your book became a sourced material for the HBO series of the same title “We Own This City,” what was that experience like for you? And do you feel that the series — I don’t know, what are you hoping the series will accomplish?

FENTON: You know, I’m hoping that for the series — for people who experience this, it validates their experiences and that also, they learn a little bit about how the police department works, how this stuff was allowed to go on. I hope that people who don’t believe this kind of thing could occur will see that, you know, these things absolutely did occur and they’re worse than they probably could have imagined. And I hope there’s just a greater understanding. You know, the police department here, I think, tried to push this — they tried to sweep this under the rug. They tried to move forward. They tried to say, that’s in the past. We’re not going to let it happen again. But that’s exactly how this went on for so many years. There was not enough reflection, not enough trying to put in place protections. And I think that people need to see this and understand that it really happens and not let these kinds of things happen. Being a part of the show making process was great. I’m a journalist but I was invited into the writer’s room with the team that created “The Wire” and other great shows, and just was there as a sounding board to throw out, you know, real-life incidents, dialogue, you know, show them videos of these officers in action so they could make sure that the story they were telling was as true to life as possible.

MARTIN: Justin Fenton, thanks so much for talking with us.

FENTON: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

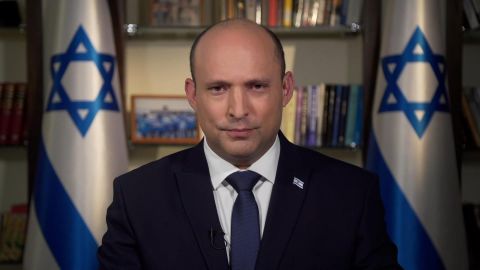

Israel’s Prime Minister gives an exclusive interview on clashes with Palestinians in Jerusalem and the war in Ukraine. Sen. Chris Murphy discusses U.S. military assistance to Ukraine. Foreign policy expert Trita Parsi explains why non-Western countries see Russia’s war differently from the West. “We Own This City” author Justin Fenton analyzes the surge in violent crime in the U.S.

LEARN MORE