Read Transcript EXPAND

HARI SREENIVASAN, CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Vauhini Vara, thanks so much for joining us. First, even in the book reviews, people have a tough time summarizing or giving people an idea of what this book is about. And as I was reading it, there seemed to be three or four different books in here running at the same time or storylines. How do you describe this to someone who has not read it?

VAUHINI VARA, AUTHOR, “THE IMMORTAL KING RAO”: So I tell people, it is the story of a small child who’s born on a coconut Grove in the south of India to a Dalit family at the sort of bottom of the caste hierarchy. He’s a precocious kid. He moves to the US in the 1970s, starts a tech company that sort of like an Apple-like tech company, and that tech company grows and grows and grows and becomes the biggest company in the world. And eventually he’s sort of king has the, the narrator, sorry, the main character of the book has engineered this sort of global world takeover where he’s sort of sitting on top of this global world government. And when the book opens we are with his daughter, Athena, who is narrating his life story from a prison cell where she is being held because she’s been accused of somehow being involved in his killing.

SREENIVASAN: It was interesting that you also chose to kind of invert the narratives that we traditionally hear about Dalits who, as you said, have been traditionally the oppressed and underclass in Indian society. Yet you’re making them out to be sort of literally the geniuses, the Kings of this entire story.

VARA: Yeah. I mean, it’s complicated. I – my family is Dalit on my dad’s side. And so when I started writing this novel, I was inspired by the – my dad grew up on a coconut grove in south India, and I was inspired by that place and wanted to write about a family kind of like his family. And his family includes, you know, really ambitious. People who went into business, my dad’s a doctor, there are lawyers. And then there are also people who, in addition to being ambitious, have really strong social consciousness who, you know, became lawyers, but went into civil rights law, right. Or who became activists or who you know, for went large salaries to do something meaningful in the world you know, regarding caste oppression in particular. And so I wanted to create a family, like a Dalit family that had all kinds of people. And King is the one who moves to the US and starts a giant tech company and eventually takes over the world. And I meant for that to be sort of subversive. But it’s also worth noting, like it’s intentional that he also doesn’t have particularly strong class or caste consciousness in the novel. There are others who play that role and he doesn’t, and I think it’s, it’s meaningful that the person who, you know, who doesn’t have that strong consciousness growing up on that coconut grove is the one who ends up starting a tech company that rules the world.

SREENIVASAN: Okay. So there are a couple of very interesting ideas that you lay out. This is kind of in the fantasy and science fiction arena. One is this idea of shareholder versus citizen, and it’s not that far fetched, but I just wanna read a brief description of it. It says,”Then my father proposed a new model. Under shareholder government policies would be guided, not by corrupt and biased politicians, but by the master algorithm developed by Coconut,” that’s the name of the company. “Using people’s social profiles as inputs, the algo would make informed decisions using not only demographic markers, but lived experience rather than pledging one’s labor to any single corporation, trading hours for dollars or other kinds of currency, shareholders would sell it at will and be compensated in social capital.” The idea of social capital is something that there are cities in China that are trying out right now. Explain it for someone who doesn’t know what it is.

VARA: Yeah. So the concept in real life is that our behaviors in the real world, you know, like our criminal records, for example, can be integrated into into a system that determines sort of how creditworthy we are, how trustworthy we are, and sort of dictate some things about what we’re allowed to do in the world. So systems like this already exist. In the novel I take it another step further and imagine a world in which a system like this dictates everything about how we are allowed to live.

SREENIVASAN: So, you know, in this notion of a company essentially performing all of the tasks of the government, that is not too far from where a lot of techno-utopian libertarian thinkers, especially in Silicon valley, want to head toward. And you are familiar with so many of them because you were a technology reporter for a number of years.

VARA: That’s right. Yeah.

SREENIVASAN: And another interesting idea that you have is this notion that you can essentially upload your memories into this, the internet, the cloud. Right. And I mean, we are living in a time when the richest man in the world runs a company where he’s essentially trying to remote control a pig’s brain and movements, you know. So it’s not that far out of the realm. I mean, I know you worked on this book for what, 12, 13 years.

VARA: Yeah, it’s really strange. I mean, for me, when I started the book in 2009, I just needed – it was like a writing – it was a writing tool. Like I was like, I need a narrative device to tell the story of this kid who grows up on a coconut Grove in India, in the 1950s and know all about it without having to actually be in his head. How, what could I do to accomplish that. Oh, I can invent a device that lets his daughter, you know, access all of those stories. And then as I was writing, you know, Elon Musk founded Neuralink, all these other companies were being founded and we’re now at a place where like this kind of technology is quite plausible and it’s yeah, it was a strange writing process.

SREENIVASAN: When you look at the polls and how well Amazon does or how well Google does and how much we trust them, oftentimes in these polls, we trust them more than government institutions or universities.

VARA: That’s right. Yeah. I mean, it does not feel hard to imagine a future in which their power continues to grow. And then because of like these breakdowns we’re experiencing in the forms of government that we have now, like, it feels – it’s easy to imagine a future in which they become more powerful. They take over certain functions and like, we feel grateful to them for doing it because no one else is.

SREENIVASAN: Yeah. Yeah. And there’s an interesting kind of twist here. The paradigm shifts in your story where I’m gonna read a little passage, “You draw a beautiful picture of the invention and post it on social, and let it multiply. And after a while, the question of whether the invention exists, whether it’ll ever exist, doesn’t matter anymore. The invention has succeeded in its goal, which is to let all the world’s shareholders live under the pretense that they can keep spoiling the planet with no consequences. In fact, they should. In fact, it’s their civic duty.” I mean, and this is in the context of a very important storyline in the book and that climate change has gotten much worse in this era that you describe in the near future. And that there are ways in which the corporations have made people essentially forget that they’re – that they have individual accountability or agency or responsibility for doing something about it.

VARA: That’s right. Yeah. I think that passage is referring, especially to the way in which by putting the spotlight on technologies that solve the climate change problem, right, it almost – like it sort of reduces our feeling of sort of social accountability for doing the hard things that we need to do to address the issue. I mean, of course these technologies exist and it’s, and they should be developed, are sort of – kind of tech utopianist way of thinking sometimes I think can be counterproductive to actually addressing the problems the way they should be addressed.

SREENIVASAN: And, you know, and I was reading this book just over the past couple of days. And of course, this is in the context of what has just happened in Buffalo and happens in so many other places. And you describe a passage in the book – it’s a little longer, but I wanna describe it. It says, “The defining sentiment of this late capitalist period was disaffection. And it began to take alarming forms. Mass murders became so frequent that they no longer trended on social. Sure you could go through the exercise of psychoanalyzing each killer in an attempt to classify him as they used to, terrorist or psychopath. But what good did that do at this scale? The only useful conclusion was the broadest one, which was that the world order itself was making people murderous, but then the politicians most equipped to address the unrest were those least invested in ending it. Began winning elections all over the world. It was the oldest trick around promising the poor members of your own ethnic group that you’d help them become as rich as yourself in large part, by making sure that the poor members of other ethnic groups stopped stealing your group’s opportunities, thus dividing the poor so that they wouldn’t rise up together against the rich.” This notion, where did you pull kind of all of this from? Is this basically from watching the news every day and deciding to make this a storyline?

VARA: It’s meant to describe a world very much like the world we live in today, you know, that description is not meant to be a description of some, you know, far future dystopian you know, world that’s, you know, that’s a twist on where we are now. I mean, everything that you just read I think it describes where we currently live. So yeah, I mean, I’m a journalist and so as – and I cover – I’ve covered social media companies and so I’m very aware of the role that they play in some of what’s going on. And then also just as a human, as somebody who watches the news and can myself feel disaffected and can myself feel sort of numb by what’s going on, I drew on that also.

SREENIVASAN: So how much of this is an amalgam of the tech leaders that you used to cover? The ones that are in the valley that are now the, you know, billionaires that run the world.

VARA: There’s something in particular, there’s one sort of key trait, I think in King Rao that came very much from my coverage of these, of these people. So I – in my early days as a tech reporter, two particular people come to mind. I was covering, or I was hired, my beat was to cover Oracle which is run by Larry Ellison. So who was, you know, I think at that time in his sixties and very prominent, very wealthy, very powerful man. So I was, you know, meeting Larry Ellison, meeting the people around him, trying to understand that company. And then at the same time I became the Wall Street Journal’s first reporter on the Facebook beat because nobody else was covering Facebook. And so I was also meeting Mark Zuckerberg and writing about Mark Zuckerberg and trying to understand him. And the thing that struck me that I hadn’t previously understood was the way in which these men were like, were quite constrained themselves, just like anybody, right? By like the pressures of investors and of customers. And, you know, as a fiction writer, you’re always looking for characters who like face challenges and face constraints and are trying to operate in a world with constraints. And we don’t think of like powerful tech CEOs as having that. Like, we sort of, I think in the popular imagination, there are these all powerful figures, but I was especially interested by the way in which like they were making these choices where it almost seemed like they couldn’t behave otherwise because of these forces pressing down on them. And so that was what I wanted to explore with King as well. You know, I didn’t think of him as somebody who can, has the power to do whatever he wants in the world. I thought of him as sort of facing these challenges and these constraints as well.

SREENIVASAN: What do you think it is about the character you created and obviously based on some of the real life humans that gives us this incredible amount of belief in them. I mean, when you, when people are pulled about how much they trust CEOs, I mean, many of them want the leadership in the country or the government to be exactly like a company. And they say, oh, well, this person’s run a company. They could probably also run government.

VARA: Yeah. I mean, I think our, I think our culture fetishizes capitalism, right? As a system, it fetishizes CEOs, I don’t think – I don’t think there’s anything like ingrained in us that makes us think that, you know, the world should be run by a CEO. I think we’ve been over time, just conditioned to feel that way, because we see how wealthy they are, we see how powerful they are. And then the message is given back to us, right? Like the message isn’t a social safety net should be provided so that people are able to have access to basic services they need, the message is, well, if you think that’s impressive, like just, you know, this is America, live the American dream. You can go ahead and get it for yourself. Right? And so we’re taught that that’s what we should try to do.

SREENIVASAN: Yeah. Yeah. And I wonder – one of the themes in the book really is about a family and someone’s long term impact and legacy. And I wondered, your dad must have read this, your parents must have read this and know that there are certain parts of it that you’ve pulled from their lives. What did they think? What did he think?

VARA: They both read it. And they were both really proud. And my dad in particular, like did feel – like he saw something of his life and experience reflected in it. And it didn’t, you know, one might imagine that it would be a little like, oof, like what, why is my family story in this book that everyone’s gonna read? But I think it felt really special to him. I mean, that kind of representation too, as a Dalit person felt meaningful to him. And the fact that it was his daughter writing it felt meaningful to him. You know, as you know, a lot of representation of Dalit people in media is created by non-Dalit people, right? So it’s like it’s writers and filmmakers who are not from that caste category trying to create these portrayals. So like, for that to happen from within his own family, felt really positive for him. He was proud. Yeah.

SREENIVASAN: That’s great. Yeah. That’s great. The book is called “The Immortal King Rao.” Author Vauhini Vara, thanks so much for joining us.

VARA: Thank you for having me. This was a great conversation.

About This Episode EXPAND

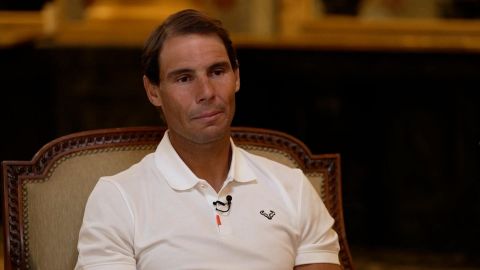

Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas discusses NATO unity. 22-time Grand Slam champion Rafael Nadal reflects on his tennis career. Vauhini Vara explains how her previous reporting on tech giants and their CEOs inspired her novel “The Immortal King Rao.”

LEARN MORE