Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: From what I can gather, you’re using that argument of right to life of future generations to make these cases. Tell me about that and that process, because it’s a really fascinating way of turning the right to life argument on its head for this crisis. And you said many courts are not climate denying, but in — but are German courts liberal courts? Were they bound to do this kind of thing?

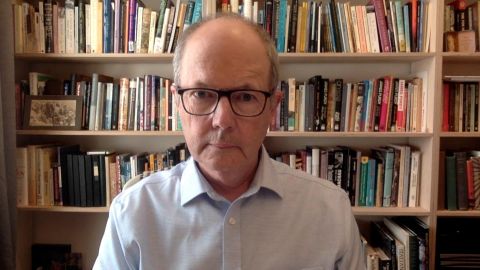

JAMES THORNTON, CEO, CLIENTEARTH: Those are wonderful questions. And German courts aren’t liberal courts. I mean, they’re not particularly progressive. When I started doing this work in Europe, German lawyers explained to me that all judges were conservative. And that was actually news to me, because I knew judges in the United States that weren’t conservative. So these aren’t particularly liberal or progressive courts. But they see the science. And the German court said that, even though the Paris agreement isn’t legally binding in this particular case, it sets the international standard. It’s a globally agreed upon standard, and future generations are being deprived of their rights now because the German law isn’t good enough. Now, what’s interesting there is that, if you just looked at the German law, I mean, it wasn’t that bad. I mean, it’s better than anything the United States has, by far. But what they said was, it was not restricting emissions early enough, so that it was putting too much of a burden on future generations. Now, immediately, too weeks in politics, two weeks of meeting, the German political parties in the governing coalition fell all over themselves after the ruling and tightened the law considerably. I think they were worried about the Green Party making headway. But the result of that judicial decision was that the German government, the Parliament, passed a much tougher law, and it’s now a remarkably good law.

About This Episode EXPAND

Carlos Fernández de Cossío; James Thornton; Chesa Boudin

LEARN MORE