Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Everything is bigger in Texas and the stakes for 2020 are huge. Former Democratic presidential candidate, Beto O’Rourke, joins us as coronavirus

transforms the political landscape.

Then what you need to know about the science, the latest with top health writer, Ed Yong.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LT. GEN. VINCENT R. STEWART (RET.), FORMER DEPUTY COMMANDER, U.S. CYBER COMMAND: If you take your knees off our neck, we will contribute to the

greatness of this country.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The first African-American head of the Defense Intelligence Agency tells our Walter Isaacson why he’s speaking out.

Plus, country music rebel, Margo Price, talks about her latest album and how COVID has hit her own family.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

Nearly one in a hundred America have tested positive for the coronavirus and the CDC is warning that the actual number may be 10 times as high,

shocking statistics that come as cases surge across 35 states. And over the weekend, Florida broke the record with 15,000 new cases on Sunday alone.

President Trump continues to attack the facts. Today, retweeting this assertion that doctors, his own CDC, the media and, of course, the

Democrats are pretty much all lying about coronavirus. That strategy, though, doesn’t appear to be playing well politically. The latest data

shows the president flagging in key states that he won in 2016. While some polls even show the race tightening in Texas, which is a gigantic state

that last turned blue, i.e., Democrat in 1976.

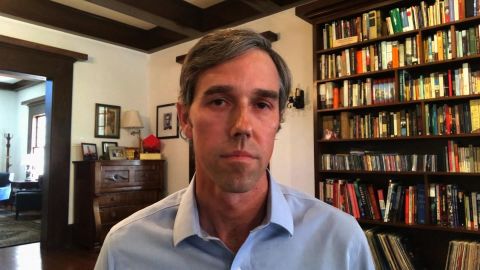

Joining me now is Beto O’Rourke, former presidential contender and now campaigner for Joe Biden. He’s joining us from El Paso in Texas.

Welcome to the program.

And there you are in Texas, which is one of the current epicenters. I just wonder how you react, and we’re just hearing that Anthony Fauci is saying

that we’re not even close to the end of this pandemic, not even close to it.

BETO O’ROURKE, FORMER U.S. DEMOCRATIC PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE: We’re not, and that’s very clear to us here in Texas. In my hometown of El Paso, we

lead the large counties in the state in the rate of deaths per 100,000 residents. In the Rio Grande Valley, south and east of where I am, they’ve

run out of hospital capacity, nurses and medical providers.

In the largest medical center on planet earth, in Houston, Texas, the Texas Medical Center, they’ve run out of intensive care unit beds, and it’s the

same story across the state. And nationally, as you know, Christiane, though we’re 4 percent of the globe’s population, we now represent a

quarter of the planet’s cases, a quarter of planet earth’s deaths from COVID-19. So, this is a tragedy borne of pride and hubris that somehow, we

are exceptional to this pandemic. And it’s the lack of leadership that has caused the suffering and death that we see throughout America, and

especially in Texas right now.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk about that hubris and that exceptionalism and also the number of deaths. We’ve got a map, obviously, that’s showing us

the massive surge in these cases. It’s in your state, it’s in Arizona, but it’s also in the, you know, Democrat-run State of California where this is

also happening.

What do you attribute it to? Because California, for instance, locked down hard and fast and was viewed as one of the most successful early states to

contain this. What is actually going on in your mind?

O’ROURKE: Let me start with Texas first because I understand this state better. We reopened prematurely on May 1st after having closed very late in

the game. We reopened not only restaurants and movie theaters and shopping malls, but we also reopened bars.

And predictably, you saw an uncontrolled spread of transmission of COVID-19 and the record number of hospitalizations and cases. The positivity count

which is now over 16 percent, and unfortunately, the deaths that have surely followed. So, the lack of leadership, the lack of political will in

closing the state down and keeping it closed until we met the metrics that will allow us to reopen explain what has happened here in this state.

In California, as you said, I think they did a great job. Governor Newsom did an excellent job at the beginning. But I would, from what I’ve seen,

argue that they perhaps opened up parts of the state and allowed things like in person dining that do not make sense when you don’t have a robust

regiment of testing, contact tracing and isolation. So, we — one of the lessons I think we need to take from this is we cannot open too soon.

AMANPOUR: And we see across the country, in New York, that they’re having a much better picture than what you’re reporting in the south, and also as

we just talked about, in the west.

So, let’s just talk about testing. That is one of the big, big things that all the experts say absolutely needs to happen, and the White House keeps

claiming that you all have a great world-beating testing process in action right now. What — how is this going to change? Obviously, it’s not the

case because otherwise we wouldn’t have this inability to trace the pandemic. What exactly needs to be done, in your view? What are you calling

for?

O’ROURKE: Leadership, in a word, Christiane. Without the CDC, without the White House providing the necessary leadership, states and local

communities are left to their own devices. And as you suggested, there is not enough testing in Texas. People are waiting in lines many hours long to

get a test. Some people can’t afford to do that, and so they aren’t getting tested. They’re waiting days and sometimes weeks to get test results back,

so you can’t even begin and implement a contact tracing program.

And when you have the president of the United States retweeting public health advice from a former game show host, Chuck Woolery, who says the CDC

is lying and you can’t trust anybody, including, importantly, doctors, instead of tweeting out the medical advice of Dr. Fauci, one of the most

respected medical and infectious disease experts anywhere in the world today, then you really have a crisis in leadership.

Here in Texas, you have our lieutenant governor, the most powerful elected position in the state, saying that there are some things more important

than living. In other words, let’s get on with the dying so that we can open this state. You compare my state of Texas with 29 million people to

the country of Germany with 83 million, Germany recorded 250 cases yesterday. Texas recorded nearly 10,000 cases yesterday.

So, you mentioned the example of New York where they’ve gone 24 hours without a single death, we look at what Western Europe has been able to do.

The only difference between here in Texas and U.S. at large is the lack of leadership.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk about, again, that leadership, because clearly, people have been left to their own devices, whether they are elected

leaders or whether they’re civilians. People are concerned, people don’t know who to believe, people don’t know whether to wear masks or not to wear

masks, don’t know whether to go to school or not to. I mean, there is just so much confusion out there.

But your country, doesn’t it sort of embody this innate contradiction, the federal, the state, the local? Your whole system is built on these

contradictions. There is no centralization, as you just mentioned in Germany and other successful countries that have got this under control

right now.

O’ROURKE: I don’t know. I think that there is a great history and tradition in America of leaders assuming the responsibility at the moments

of great crisis. So, think about Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the midst of the great depression and then facing Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan in

World War II. I think about John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis and making sure that this country was up to the single greatest existential

threats we faced at the time, banding us all together in common cause, be us Republicans, Democrats or independents.

Christiane, I was thinking about this metaphor earlier. What if during the blitz in London, in 1940-1941, some people had claimed personal liberty as

a justification for leaving their lights turned on so that Nazi bombers could find their homes and communities? Those who don’t wear masks here in

the United States, and I just saw a picture of Texas senator, Ted Cruz, flying on an American airlines flight without wearing a mask. What if our

personal liberty here in Texas as an excuse for not wearing masks or not staying at home or not having stay-at-home orders is, in fact, infecting

and making other people sick and killing our fellow human beings. That’s what’s mapping right now.

So, this is a moment for shared sacrifice and service and the struggle against COVID-19, and all that is wanting right now is a leader, a leader

in the White House and a leader here in Texas. But thankfully, we have elections coming in November and that’s where we can choose new leaders to

meet this moment and this challenge.

AMANPOUR: So, you know, again, we’re talking about the experts and leaders. Dr. Fauci has said the states have gone from total shutdown to

completely throwing caution to the wind. So, he’s trying to fight the good fight as his position as chief medical officer, chief scientific officer,

chief infectious disease specialist for the United States. And yet, the White House is basically slagging him off and creating a huge amount of

wall of opposition against the facts.

So, do you expect it to get worse in your state as people become even more confused and those who are predisposed not to listen to the experts simply

take, you know, that kind of encouragement not to?

O’ROURKE: You know, the spirit of your question lays out just how deadly and dangerous the president’s conduct is right now. Here you have the most

esteemed public health expert in the country, one of the most esteemed in the world, Dr. Anthony Fauci, trying to give this country the guidance and

direction it needs literally to save the lives of our fellow Americans. And you have the president of the United States with the loudest microphone and

the greatest Twitter following saying the exact opposite. Literally he’s telling people not to trust doctors and public health experts.

Only yesterday, for the first time after months of this pandemic raging across the country, publicly wearing a mask. This president, Donald Trump,

has killed the people whose safety and security he was elected to be responsible for. So, these are the stakes right now, and it is incumbent

upon us in our personal lives, at the local jurisdiction level to do all that we can in the face of this gross incompetence and this deadly lack of

leadership from our president.

So, you know, whether it’s following the advice of mayors and county judges, those governors who are doing the right thing for what we can do in

our own lives, as you said earlier, we’re left to our own devices at this point, and it is the worst point to be left to our own devices as this

pandemic continues to rage in states like mine.

AMANPOUR: So, Beto O’Rourke, you just said a couple of very, very harsh things. You said deadly politics and you said has killed the people that he

was elected to protect. Do you believe that this will come back to bite him during the November election? Do you believe, for instance, that your

state, which has never gone Democrat since 1976, might do so this time? You’re campaigning for Joe Biden. What do you think the accountability

factor, I suppose, will be in November?

O’ROURKE: You mentioned in the introduction that the race between Joe Biden and Donald Trump in Texas is beginning to tighten. I would actually

argue that it is already tightened and Joe Biden is beginning to increase his lead and foreseeably walk away from Donald Trump in a state that is the

biggest battleground state for the electoral college in the United States. 38 electoral college votes, which as you mentioned, have not been won by a

Democrat since 1976.

If Joe Biden wins Texas, it is game over not only for Donald Trump, but it fundamentally changes the electoral landscape and what is possible here in

the United States of America. That’s why it’s so important. And then this, we know that this president does not respect the rule of law or the U.S.

constitution. My belief is, Christiane, if this election is close, even if Joe Biden has lawfully won it, the president will try to introduce

confusion and chaos about the results in an attempt to steal the election. He’s already signaled that by calling out mail-in ballots and fraud from

Democrats.

If Joe Biden wins Texas, then the result is unambiguous. There is nothing to create chaos or confusion about the election is over, we turn the page

and begin a new chapter. So, I want to make sure that we do everything we can to register every eligible voter in Texas and then help them to make

the decision to turn out in November. Texas can win this for Joe Biden and Texas can help set this country in the right direction at a moment it

desperately needs it.

AMANPOUR: Beto O’Rourke, thank you so much. And you’ve laid out how really the United States is at a crossroads right now, not just within, but in the

world as well. Thank you so much for joining us.

And we are now more than seven months into this pandemic, and the scientific community is still learning. The latest research is showing that

coronavirus can damage all major organs of the body and ravage the body with blood clots. While a new study from King’s College here in London

report that any immunity that maybe won from having had the illness could in fact be lost in months.

To help us make sense of all of this information is Ed Yong. He is the top science and health writer for “The Atlantic,” and he’s joining us from

Washington. D.C.

Welcome back to the program, Ed.

You know, with all these facts that we’re seeing in terms of infections rising and, you know, cities like Austin, Texas making a convention center

into an emergency hospital unit just in case. Where do you see — the first question, I suppose, where is this going to go in the next weeks and

months, do you think?

ED YONG, STAFF WRITER, THE ATLANTIC: I don’t think we’re on a very good trajectory. Much of this was predictable. Experts warned if states rushed

to reopen too quickly, we would see rises in cases. We have seen that. They predicted that rising cases would soon be followed by rising deaths. We are

seeing that now.

And a lot of the near-term future is sort of baked in. There is a long lag between people going out and about with their normal lives, getting

infected, then showing symptoms, then being sick enough to go to hospitals, then dying and showing up in national statistics. And that means that what

we’re seeing now are the consequences of actions that people took about a month ago and the things that people are trying to do now to desperately

stem the tide of this new surge will take a month to manifest.

Meanwhile, we will see more cases, more hospitalizations, more deaths. And this is why the country needs to be watchful. It needs strong leadership,

like Beto said. It needs to be prepared for what is to come rather than constantly playing catch-up to this virus.

AMANPOUR: Let me just play, because we talked about Anthony Fauci. We know that he’s now in a war, if you like, of rhetoric with the White House, not

of his own making, but the White House is launching this war against him. He is speaking in a webinar to Stanford University. I just want to play

what he said about what states could do now, or should do.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DR. ANTHONY FAUCI, DIRECTOR NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ALLERGY AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES: We did not shut down entirely, and that’s the reason why, when

we went up, we started to come down and then we plateaued at a level that was really quite high. You don’t necessarily need to shut down again. But

pull back a bit and then proceed in a very prudent way of observing the guidelines of going from step to step. There are things you can do now,

physical distance, wearing a mask, avoiding crowds, washing hands, those things, as simple as they are, can turn it around.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, Ed, he’s not being alarmist. He’s saying we don’t need total shutdowns again, there are step-by-step measures that can be taken. He’s

also saying we’re not nearly at the end of this pandemic, and that this is the big one. This is the perfect storm, the transmissibility, the ferocity

of how it just moves around from human to human.

What are you learning? What is the scientific community learning, if anything more, about it since, let’s say, the last time we talked a month

or so ago?

YONG: Well, so, just to clarify, this is not the perfect storm, this is a big one, sure. It has upended the world, but this is nowhere near as bad as

a pandemic could be. This virus does not have the lethality of other coronaviruses, like SARS or MERS. It does not have the transmissibility of

something like measles.in some ways, this really is a pandemic and it should be truly humbling and worrying to us that we are flunking it so

badly.

One thing that really worries me, and to answer your question about what scientists have been learning, is that we are — it’s becoming very clear

that this old caricature of the virus, that it causes, in a few cases, severe enough illness to send people to hospital, and in every other case

it causes only mild illness, much like a cold, is just wrong.

We know that there are thousands, perhaps tens of thousands of people, who have — whose lives have been incapacitated by this virus. They have not

been to hospital, but they have been sick for months on end with rolling waves of symptoms that we still don’t understand. And I think that should

give us pause. There are a lot of people out there who think because they are young, because they are not in these at-risk groups that they are sort

of invincible, that they are immune to this virus. They won’t face the consequences if they don’t die. They might do.

The virus seems to be able to cause medium to long-term disability in the way that a lot of other viral infections do, and we are not grappling with

that. And I think that should help — we don’t understand the extent to which that’s happening, and I think it should really give us pause when we

think about reopenings and we think about our own personal risk calculus.

AMANPOUR: How much do you worry about the debate now over asymptomatic transmission? We know the doctor in Germany, you know, people who are very

forward and, you know, forward-leaning and medically sound on all of this, they say they missed, you know, elements of what they needed to understand

early on, the asymptomatic transmission.

YONG: You know, I would say that asymptomatic transmission was very much on the cards even back in March, and the case for it was abundantly clear,

at the very least by April. So, we’ve known about that for a while. That is why people have reacted in the way that they have, called for stay-at-home

orders, strict to social distancing, the wearing of masks to prevent people who don’t know they’re infected from spreading the virus to their

neighbors, their friends, their families. We knew this. This bit hasn’t changed.

And remarkably, I would think, despite the illusion of something that changes all the time, the science of this virus is actually been in its

foundations very solid for a long time. We have simply failed to make use of it, to act on the advice of experts that actually have been pretty

consistent for several months now. This is not a scientific failure, what is happening to the U.S. in COVID-19, it is a political one.

AMANPOUR: What about the medical issue, it has not been peer-reviewed, I have to say, but King’s College, which is doing a huge amount of research

here in London has the first parts of a study which say that even if you have had the virus, the immune effect of it, the antibodies, could

disappear within a very short period of time.

YONG: So, we know that the length of immunity varies widely even with other coronaviruses that we know much less about. It’s less than a year for

things — for the more common coronaviruses that cause common colds, much longer for things like SARS and MERS. So, we don’t know the extent of

immunity for this one.

What I will say for interpreting studies like this that you’re mentioning is that there is a massive difference between what is possible and what

actually happens. So, because something is seen in a patient or a small number of patients, it doesn’t mean that’s going to be the norm or even the

average situation. And we need to be very clear about that. We need to sort of distinguish between what the extremes of what could happen and what

actually is most likely to happen.

And the extremes are going to be very wide. This is a pandemic. It’s affected millions of people around the world, which means that you’re going

to see unusual events, strange circumstances happening actually quite often. And we need to bear that in mind when we interpret all kinds of new

data about COVID-19.

AMANPOUR: Your latest article in “The Atlantic” talks about the people on front line, basically the doctors, the researchers who are working, you

know, nonstop to try to figure out treatment, a vaccine, all the rest of it. You mentioned politics has been driving a movement from the White

House, anyway.

How is this affecting the people you’re talking to, the actual medical and scientific profession, the human beings who are trying to save lives?

YONG: I think it’s really crushing their spirits. It’s so demoralizing to get a chance to serve your country, to martial all the expertise you built

over decades of training and really put it into action and to see that expertise, that advice, all your attempts to help the world be just

battered down by folks who dismiss it, who just dismiss out of hand, you say contradictory things, who don’t listen to it, who, in that actions and

policies that reopen things before they are ready and that then lead to very predictable consequences that those same experts have feared.

But being — working in preparedness is already a little bit of a miserable experience, because you’re constantly having to envisage the worst possible

scenario and prepare for it to happen. And when you actually see that the worst-case scenario that you have long feared is happening again and again

despite your best efforts, it’s hard. You know, I think a lot of the experts I’ve spoken to over the course of this pandemic have — are really

struggling. I think they are finding it difficult not just because they’re not being listened to, but because a lot of them are being especially

attacked.

This is happening specifically and disproportionately to women, to women of color in particular, and, you know, it’s contributing to this atmosphere of

demoralization that is harming the people who we most rely upon now in the middle of this pandemic at the point when we need them the most.

AMANPOUR: It’s really concerning to hear you say that, particularly about the disproportionate attacks on women and women of color. It’s really

disheartening that this is even politicized in that degree, to that level. Can I ask you lastly, all the talk about a vaccine, where do you stand?

Where are you looking for the best answer to where one might come from, how long, et cetera?

YONG: You know, if you had asked me this question earlier in the pandemic, I would have given you a science-based answer about lengths — how long the

process of vaccine creation would take. Now, I would give you a sociological answer. I would say that what — the question that most

concerns me is not how long will it take a vaccine to arrive but can a country that is doing so badly as we are right now at controlling COVID-19

roll out a vaccine in a way that is equitable, efficient? And I’m not sure I have faith in the process.

So, let me give you three predictions for vaccines. Firstly, that a lot of people are going to resist the very idea of getting it because they’ve been

told for months, years now, not to trust experts, that the people who have been most marginalized during this pandemic, who’ve been disproportionally

hit, black, brown, poor, indigenous, disabled, elderly people who will be lost in line to get a countermeasure that’s been developed, and that the

deployment of such a vaccine is just going to be a logistical nightmare.

A country that’s seven months into a pandemic still cannot ensure that its health care workers have enough gowns and gloves and protective equipment

is not going to be able to distribute a vaccine in an effecient way. It simply isn’t.

And so, I worry a lot about even this end game being another area, we look back on with dismay. And we need stronger leadership, we need more actual

leadership if we are going to deal with this. We can’t just rely on a biomedical silver bullet.

AMANPOUR: It’s really, I have to say, disheartening but nonetheless bracing to listen to you tonight. Ed Yong, thank you and for all your work

on this, it’s really important. Thank you so much.

Next, we have an exclusive interview with the first African-American to serve as director of the Defense Intelligence Agency that was under

President Obama. Lieutenant General Vincent Stewart retired last year after nearly four decades of service with the U.S. Marine Corp. After George

Floyd’s death, he felt compelled to speak up for a future of generations of black American in an op-ed called “Please Take Your Knee Off Our Necks So

That We Can Breathe.” And here he is speaking with our Walter Isaacson in first TV interview since he wrote that article.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And General Vincent Stewart, welcome to the show.

LT. GEN. VINCENT R. STEWART (RET.), FORMER DEPUTY COMMANDER, U.S. CYBER COMMAND: Thanks, Walter. Yeah. Delighted to be here.

ISAACSON: Tell me your feelings as you watched the video of George Floyd being murdered.

STEWART: Two images that are burned in probably forever. The first image is probably early in the confrontation, and you see the two pictures, the

two faces, Officer Chauvin on top, George Floyd on the bottom, having Officer Chauvin’s knee on his neck. And the image of face — the expression

on Officer Chauvin’s anger, dominating position, just in total control of the situation. And you look at the image of George Floyd on the bottom,

fear and great concern for his position that he was in, that it’s such a juxtaposition of the dominance of one and the fear and dread of the other.

Fast-forward, about eight minutes later, and you look at George’s image. His eyes are closed, his body is lifeless, and I don’t know if he’s dead at

that point, but the expression is different. And Officer Chauvin on top, very calm, very nonchalant, very much in control. And three images when you

see them, if you’re not touched by those images, I would question your humanity. And that’s a harsh statement. And I think every African-American

who saw that had to have been touched. Every American who saw that should have been touched. And at that moment I realized that I could not be silent

anymore.

ISAACSON: You had spent a career in the military, rising to the top ranks, becoming a general at the Defense Intelligence Agency and many other

places.

But then you decided you had to write an article, something you really hadn’t done much before, speak out on race. Why?

STEWART: There’s two parts, one, that incredible image.

But the hard — it wasn’t courageous to write that article. It was painful. And the painful part of it was, in spite of all the things that I had

endured, I could not protect my children from enduring bigotry and hatred and racism.

And if, in 2020, we’re still following the pattern that we’ve had throughout the history, my grandchildren would not be protected. I have 15

grandchildren, all ages, size, demographics. We are the American dream.

But I have got a young granddaughter who I’m thinking, goodness, we’re going to keep doing this cycle over and over again. And I may not be able

to protect her. And, again, that’s the reason I had to speak up.

I would not have been credible speaking up as a captain or a major. I was certainly credible as a retired three-star, former director of the DIA.

Folks would listen, and it might make a difference.

ISAACSON: Tell me about the title you chose.

STEWART: There are a couple of things that happens if you have your knee on our necks.

Well, the first thing that happens is, you will die, like George Floyd. If you are being suffocated, you will die. If you take your knees off our

neck, we will contribute to the greatness of this country. We will contribute — we will be — participate in this democracy. We will help

this country, because we have diversity, not just the diversity of color, but diversity of thought and ideas.

So, you have a choice in this case. Let us be part of this environment. Let us be part of this democracy. Let us be helpful in making America truly

live up to its ideals, or wipe us all out, kill us one by one, and not have the contribution that we can add to this society.

ISAACSON: In your op-ed, you write: “It’s hard for me to explain the pain.”

What is it you have faced? Can you tell us about that?

STEWART: It’s incredibly painful to think that, if I were — and it doesn’t happen now — when I was younger — I’m outside the demographic

that gets attention — that if I were — if I thought I was going to be stopped by a police officer, I didn’t think that police officer was going

to be my friend and we would have a trusting conversation.

I believed that I was, at that moment, in a confrontation, a fight-or- flight environment. And so how do you protect yourself? You make sure your stop is under a streetlight, where someone will see you. You make sure the

stop in an environment where others might see you.

And to live that every day, to just — in almost exasperation, just go, OK, I’m going to be stopped. I know I’m going to be stopped. How am I going to

deal with it? Am I going to try to get out of there? Am I — how am I going to be deferential to this officer so he knows I’m submissive right from the

very beginning, even if I have done nothing wrong?

And to live that every day, and to try to convey to another demographic that this is the life of an African-American, even today, that you’re going

to be stopped for no other reason than someone wants to ask where you came from, where you’re going, but the underlying issue is, you’re a bad person,

and I need find out what you have just done wrong, so that I can take you to — and that’s hard to live.

ISAACSON: The most powerful parts of your piece were where you describe your own — things that happened to you, first when you go to Chicago,

emigrate there from Jamaica, and then step by step how you got touched by racism.

Describe some of those for me, please.

STEWART: Yes.

I remember my first — my first fight in America was racist. And this was a young man who I ended up playing on the same football team. We were at the

park in the North Side of Chicago, a bunch of us who looked like me playing baseball confronted by a bunch of folks that didn’t look like me.

And I don’t even know why we even started the argument, but we ended up in a pretty good brawl. And that was the first time anyone ever — as far as I

remember, the first time someone used the N-word in a confrontation.

And I can’t tell you how many times I have seen folks who, in anger, immediately default to N-word. And that genuinely tells me what’s in their

heart. It would be one thing to call me out and go, you’re tall and you’re ugly or you’re fat or whatever.

But they default to that word, which has a very specific connotation to it. So, that first fight was the first fight, the first time I have ever been

called a nigger. And it struck me at that moment how different my environment was.

And this was maybe my first freshman year in high school.

ISAACSON: Then you joined the U.S. Marine Corps. And one of the sayings in the U.S. Marine Corps is that there are no black Marines, there’s no white

Marines, there are only green Marines.

Was that your experience?

STEWART: I think that was the ideal.

But we draw in the Marine Corps from a cross-section of society. So there are probably people who believe that performance is the only thing that

matters. But there are also people, because we draw from society, who thought, yes, but he is a dark green Marine, and that makes him different

than a light green Marine.

I think the Marine Corps generally tries to emphasize, if you deliver, if you perform, you will move up by merit. But, again, we have folks from all

sections of society.

So I’m not naive enough to believe that during my time in the Marine Corps that I didn’t encounter people who had some level of bigotry and some level

of hatred, some level of superiority, some level of racism.

ISAACSON: Why are there not more black officers in the Marine Corps?

STEWART: On the enlisted side, we have done a remarkable job.

I’m not sure I understand why — you look at the enlisted demographics, and it looks pretty good, all the way throughout, all the way to the top of the

pyramid.

You look at the officer side, and go back, we’re not recruited enough at the base. And we’re doing targeted retention. But if we’re serious about

getting people to the top, we got to have some different approaches. It’s not going to happen organically. It’s not going to happen because you don’t

have a base. It’s not going to happen if you don’t target recruiting and if you don’t place some jobs that will make them competitive.

What I challenge everybody, both in the private sector and the military now, is, take a look at who is in your front office, because the people who

are in your front office are your future leaders. They’re exposed to the senior decision-making. They’re getting their evaluation written by three-

and four-stars. They are other general officers who are going to sit on their boards and recognize them.

And so if the demographic in your front office looks like one particular demographic, then we shouldn’t be surprised when they show up on the

command list and when they show up on the general officer selection list.

ISAACSON: The George Floyd death, murder, and COVID-19 both could have led to conversations that you talk about that would have united us, that would

have brought us forward, as you say.

Do you think our national leadership is conducting those conversations in ways that unite us?

STEWART: No.

And I guess I should probably help define that. Those are two great examples where, if we wanted to bring America together, we could galvanize

America around two really serious issues.

Instead, it’s become partisan and divided. And it’s continued a path of division that cannot be healthy for our nation. I could imagine truly going

to war against the pandemic and making this a unified approach to how we defend our nation against this virus.

But you now see blue and red states and how they’re doing in terms of dealing with it, and both sides are on different approaches to solving

this.

So, national leadership is — I think we lost an opportunity to bring the nation together in this — both in those cases, both in terms of the

pandemic and in George Floyd. And I think that’s to the detriment to our nation.

ISAACSON: When you retired, you said you did it partly because you were just tired.

But was there something else in it that made you say, I have got to leave, I’m not comfortable with the leadership?

STEWART: I left because I was tired.

I left I — because friends my age were dying. And I wanted to spend more time with my family and my grandchildren. I also — I don’t know that I

could have — one of the things I worry about is the politicization of our military leadership.

When I see the chairman — and I know the chairman did not want to be where he was, but I see it too many times, where we rolled out our chairman and

chiefs of staff as a backdrop to something that is political in nature.

And I could see that coming, and I did not want to be a part of that. I think it’s absolutely dangerous to our society and our democracy that our

military is politicized. And, sadly, our leadership sometimes don’t have a choice.

If our political leaders say, we want you at the White House to be there, they probably are arguing that we probably shouldn’t be there. But if the

commander in chief says, you should be there, guess what? You have got a couple choices. You can walk out the door and go, OK, I can’t do that, I

don’t support that morally, or you can show up, because your commander in chief says, show up.

And so you get a really tough choice. I can walk out the door or I can go be a prop.

And I can the anguish and pain when the chairman and the chiefs are standing there. They’re trying to be stoic. They’re trying not tip, yes, I

agree, or, yes — no, I don’t agree.

But I didn’t like the idea of being a prop, as I think a misuse of our military leaders.

So that was a factor in my going home.

ISAACSON: When you talk about being a prop for the misuse of the military by our political leaders, are you also thinking about what happened in

Lafayette Square, when the president cleared it out so that he could stand for that photo-op?

STEWART: I think that was a terrible position to put the chairman in.

And, yes, if you’re talking about rolling out the military to suppress peaceful protests, and you’re willing to use military, what better — from

a political standpoint, what better way than to have the chairman be there as part of that message?

And I know General Milley didn’t want to be there. I know he probably regrets to this moment being there. But I thought that was a terrible,

terrible optic. And I don’t know that he had much choice in the matter.

But that sends a terrible message to the American people that we’re ready to use our Army to suppress a peaceful protest. It was a bad place. I’m

very glad I didn’t have anything to do with that.

ISAACSON: What’s at stake, in your mind, in this election?

STEWART: I’m going to steal from Jon Meacham’s book, the soul of America, the soul of America.

And we have been wrestling with this throughout our history. Who do we really want to be and what do we want to represent, not only to our

children here at home, but to the world?

And that, to me, is what this election is all about. It’s, are we going to be the bright light on the hill? Are we going to preach to countries about

human rights and rule of law and justice, and then we hold a mirror up to ourselves and we’re going, we’re not just, we don’t necessarily buy into

the rule of law, we are doing things that make us look like bullies on the international stage?

Nations around the world have got to be looking at this thinking, how hypocritical. What a different set of standards.

So, if we can’t be the example — and I ended my piece with, I still believe in America, but America will be great if America is good. And

America will be great if we’re an example to the world. America cannot be great if it is being as hypocritical on the international stage.

America cannot retrench and not be of this global community. The world has always needed what we stood for from the beginning of our Declaration

through our Constitution, warts and blemishes and all.

We have got to be an example to the world. And right now, we’re not a really good example.

So, for me, that’s what’s at stake this election.

ISAACSON: General Vincent Stewart, thank you so much for being with us.

STEWART: Thank you very much.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Such important insight into crucial separation of law and state and also, of course, rule of law.

Finally tonight, Margo Price, a country music star who is not afraid to speak truth to power, she’s making waves with her latest album, “That’s How

Rumors Get Started.” It weaves together issues from motherhood to health care and beyond, including the rock-heavy hit single “Twinkle Twinkle.”

Take a listen to this clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

(MUSIC)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: A powerful riff on the price of stardom.

And Margo Price has quite the backstory, too, having experienced prison and homelessness. She funded her first album by selling her car and her wedding

ring. And she’s joining me now from Nashville.

Welcome to the program, Margo Price. It’s a wonderful album. It’s really listenable. Congratulations. It’s your second big one.

What inspired you on this one, and tell me about the title song. Why did you choose that title?

MARGO PRICE, SINGER/SONGWRITER: Yes.

This is actually my third album. And “That’s How Rumors Get Started” was something I heard in passing. And I just liked the mystery behind it. But I

think we live in such an age of mistruths and rumors, and, you know, it has a little bit of ambiguity there.

AMANPOUR: People put in air quotes you’re sort of a country music rebel, country music outlaw. You certainly talk a lot about truth, and there is a

saying, of course, that country music, all you need is three chords and the truth.

You speak a lot about it, from whether it’s, as I said, the health or gender issues, the pay gap, et cetera.

What gives you that, I guess, the cojones to go all that way, given how difficult it is for women in the country music sphere?

PRICE: Yes, it certainly at times can be a very misogynist, even racist genre. And I think for, so long, people have these misconceptions that

anybody who plays country music is going to be right-winged or not liberal.

But I come from a long background of blues and folk music. And this album, I think, is a little bit more rock ‘n’ roll.

But, certainly, living in Nashville and being part of the anti- establishment, I have never wanted to fit inside the mold that was set there by many of the organizations in this town. And it’s been challenging

at times to speak out about issues like gender inequality or gun control, but I think that someone needs to be saying it, and I’m happy to lend my 2

cents.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, because, look, it’s not easy to do it, and we just talked about the misogyny and how you actually forged your own path

towards getting your albums first published. I mean, you had to do it on the Jack White label, one of the first ones.

You did a different route to what others have done. Does that protect you? Does that give you the space to be able to be as political as you are? Or

has it been difficult?

PRICE: Well, I definitely think I have lost some fans by some of the things I said.

My first album, “Midwest Farmer’s Daughter,” which my husband sold the car for, and we kind of went all in, that was more about my personal story and

about — it was kind of anti-establishment with the music business. And then my second album, “All American Made,” where I spoke out about the pay

gap and asked how the president sleeps at night, that definitely threw people for a loop.

And I think I have just been kind of weeding out those really narrow-minded fans. And I’m just kind of trying to follow my gut and navigate things the

best I can just through following my heart.

And especially with everything that’s going on now, I have really been wanting to help elevate the voices of Black Lives Matter. I spoke on the

Opry this Saturday night, and made some comments about the Black Lives Matter movement.

And I definitely got a lot of negative response from some people, but the Opry themselves was very supportive. And I hope that some of these

institutions are kind of coming around to doing things a different way and to realize that we all need to be united in this country to move together.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

I mean, look, you raise a really important matter of social justice that has been again raised by the killing of George Floyd. Maybe not country,

but so much music depends on black artists and black creative genius.

How do you see music’s role in joining this fight for racial justice?

PRICE: Well, I think that country music owes a great deal of debt to black artists and black music. The blues and folk and even the banjo came from

Africa.

And I think there’s been so many misconceptions of where country music comes from and who plays it. Hank Williams was influenced by black

musicians, Johnny Cash. But the list goes on and on.

And I think that, as far as the bigger picture, no matter what your medium is for telling your songs and your stories, I think that we all have a

responsibility right now to elevate the voices of our black brothers and sisters.

And especially in the country world, where a lot of the fans might not be so open-minded, I think that — it’s just getting the conversation going,

that’s what we need to do. We need to be talking about it.

And when people say that there is no racism in this country, then they’re living under a rock and they’re living by white privilege. And so I think

sometimes it’s hard to hear the truth and it’s hard to hear what we need to do. But I know there is a lot of white corporate feminism out there.

And I have been a voice for women’s rights, but I have tried to be a voice for people on also — no matter what color they are or no matter what their

sexual orientation is, I think we just need to learn to be more accepting as a nation to all of our people that live here.

AMANPOUR: Yes. And it’s around the world as well, as you know.

You mentioned your husband a while ago. And we’re going to ask you to expand, pull out the shot. And we are going to see Jeremy Ivey, who is not

just your husband, but he’s also your a creative partner and an artistic performer, obviously, in his own right.

And I want to ask, because we have also had this coronavirus pandemic that you’re going through that has probably curtailed your publicity for this

album.

And, Jeremy, I think you think you had it, right? How has corona affected your family, and you specifically?

JEREMY IVEY, MUSICIAN: Well, I’m — yes, I’m positive that I had it.

The tests were kind of weird and came back indeterminate. But I have had friends that died with a test result.

And I have talked to a lot of doctors about it. And, I mean, there’s very little chance, with the symptoms that I had, that I had anything else.

But, yes, it was scary. I had to deal with maybe the idea or thought that I wasn’t going to make it through. And you have to learn to live gracefully.

We ought to also have to learn how to die gracefully. And I feel like I was getting my affairs in order.

And when I got better, I think that it — I really learned something from the experience. I had to face that idea.

AMANPOUR: Wow. Yes.

And I’m sure it all goes to your experiences in music as well.

And I just want to ask you both, because I know you’re going to play us out. You have chosen — I want you to explain the song you have chosen. I

believe it’s for your son, your oldest son, and why you have chosen this.

And then play us out as we say good night. And thanks for watching.

Margo and Jeremy, thank you very much for your rendition of “Gone to Stay.”

PRICE: Thank you so much for having us.

This is a song that we wrote to our children. And it’s a message of, when we’re gone on the road, to know that we’re always with them, but also to

know that, when we’re gone, and when we pass, this is a message that we wanted to give to them on how to treat other people and what to leave

behind, and to not take so much from this struggling Earth right now.

So, this is when I’m gone.

(MUSIC)

END