Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

More than a billion children around the world are out of school, and getting them back can be a life or death decision. I’ll speak with the

school’s superintendent in Mississippi, facing that dilemma as infections are already rising. And to Arne Duncan, the former secretary of education,

who’s “furious” at leaders who put kids in danger.

Then, Megan Rapinoe, superstar athlete, activists and role model, takes on a new challenge, hosting a new political talk show for HBO.

And later —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DR. FRANCIS COLLINS, DIRECTOR, NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH: Seeing the suffering and death around us from this pandemic, I’m not immune from

wondering would a loving God allow such a thing to happen.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Dr. Francis Collins, Anthony Fauci’ boss, on faith, science and hope for an effective coronavirus vaccine.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Lebanon, which one of the worst hit Middle East countries from coronavirus, teetering on the brink of economic collapse, has now suffered a huge

explosion. It originated at the port of the capital, Beitut. Just take a look at this dramatic video.

Local authorities are warning that many are injured and buildings across the city have been damaged. Let’s get straight to it with our Ben Wedeman

who is standing by at the bureau, which has also not escaped the aftershocks. Ben?

BEN WEDEMAN, CNN, SENIOR INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Yes, that explosion, Christiane, happened just a few minutes after 6:00 p.m. local time, that’s

about three hours ago. I was in the CNN bureau here in downtown Beirut.

Initially, it felt like an earthquake, but just moments later these windows were completely blown out, the frames blown out, our front door is gone

now, and that scene has been duplicated, replicated throughout the city. I have spoken with people all over this town by phone, and they all say the

same thing. This is an explosion the size of which many who have been through the civil war, through the 2006 Lebanon-Israel war, never have seen

an explosion of this magnitude.

The hospitals here in Beirut are overwhelmed with the injured. The Hotel Dieu tells us that they have accepted at least 400 injured, another

hospital getting at least 60, and that’s just two hospitals. The Lebanese Red Cross has called for all of its ambulances in the entire country of

Lebanon to come to Beirut immediately to help with taking the injured to get treatment.

Eyewitnesses are telling me that they saw people being treated on the street, others been given CPR on the sidewalk. There is no part of this

city where damage has not occurred. The number of dead is still not clear. This was preceded by some sort of fire in a warehouse in Beirut’s port. The

national news agency, the official agency, said that the warehouse was full of fireworks, but Abbas Ibrahim, the head of Lebanese General Security,

said it would be naive to think that an explosion of this magnitude was caused by mere fireworks.

But at this point, it’s unclear what was the cause of that explosion, but what is as clear as day is that this explosion has wreaked incredible

damage throughout this city. The number of casualties and fatalities at this point is unclear, but it is going to be for sure significant in

number. Christiane?

AMANPOUR: I mean, it really does look horrendous, and just where you’re standing just testimony to that. But let me ask you this, because it has

been really, really troubled, Lebanon, by the recent events, the pandemic, the economic crisis. How does this add to the crisis in Lebanon?

WEDEMAN: It’s just another nail in the coffin of this country. This country is in a state of economic collapse. The local currency, the lira,

has lost about 80 percent of its value. In the last three months, every month, prices have gone up by 50 percent. Unemployment has skyrocketed. You

see people on the streets of Beirut rummaging through the garbage looking for food, there are more beggars than ever on the streets. This country is

falling apart. And this is the absolute worst thing that could have happened to Lebanon at this stage. Christiane?

AMANPOUR: Ben, thank you so much for bringing us up to date, and of course we’ll continue to watch it.

But Lebanon, of course, is one of the 160 countries where schools have been disrupted by coronavirus. The U.N. secretary general, Antonio Guterres,

says, the world faces a generational catastrophe with families forced to make impossible choices, return to school and risk infection or stay at

home and suffer the developmental and educational consequences?

Meanwhile, the crisis exacerbates existing inequities between race, class and various different countries. In the United States along with Congress

deadlocked over emergency aid for school, President Trump simply tweeted this, open the schools.

Now, for context, 13 U.S. states report higher infection rates per capita now than the current global hot spots which are Peru and Brazil. One of

those states, Mississippi, is on track to be the top state for coronavirus infections. The school district in the City of Corinth did reopen its doors

last week. And Dr. Edward Lee Childress is superintendent there, and he’s joining me now.

Dr. Childress, welcome to the program.

You obviously, like so many officials all over the United States, under quite a lot of stress trying to figure out what’s best for your students.

Tell me what led you to reopen the schools a week ago, and how has that panned out in Corinth?

EDWARD LEE CHILDRESS, SUPERINTENDENT, CORINTH SCHOOL DISTRICT, MISSISSIPPI: We made the decision to reopen our schools based on several factors. One of

the factors was that we had factored in that there would be a summer surge that we would be experiencing at the time we were scheduled to reopen

schools. We are on a modified calendar, and that would be one of the reasons for our early reopening.

We had been sharing and bringing parents in our community along with our process of the plans to reopen schools for about a 10-week period through

social media platforms in which we gave parents the opportunity to comment, we conducted surveys. And ultimately, the administration made a

recommendation to the board that we plan to reopen our schools.

AMANPOUR: Dr. Childress, of course with the best of intentions, you did that, and then we understand that several infections have happened, there

have been kids who have quarantined, several dozen kids quarantined. What have you now done? Have you closed the schools under your jurisdiction?

What are the parents saying, the teachers? What state are you in right now?

CHILDRESS: The schools currently remain open. Just as you have mentioned, we have had five positive COVID-19 results among students in our schools.

We were open for five days before we had the first positive. Then in the last couple of days, we have identified four additional ones.

Our schools are still open, teachers are teaching, and I’m going to have to go back to, you know, last Monday when the schools reopened. It was amazing

to see the energy exhibited by the teachers and the excitement of the children for their return to school. Because in many cases, for them, they

return to a sense of normalcy that they had not experienced since last March. So, while we have had positive cases among students, while we do

have students quarantined, I have been in all three schools today, and learning and teaching is definitely occurring.

AMANPOUR: Dr. Childress, one of the sort of main issues has been for all to see that there’s been a lot of different kinds of instructions from

state to state, you know, county to county, you know, from the north of the country to the south. It’s just a lot of different instructions. No one

size fits all.

So, what are you doing, for instance, regarding the different ages of kids? Have you found that certain ages are more vulnerable or more prone to

spreading? Are there different rules? And what would it take for you, what kind of level of infection, to close down your three schools?

CHILDRESS: As you have pointed out, you know, there have been identified studies that have talked about the levels of infection at different ages of

children. And we have looked, and some of the measures that we have put in place do depend on where the schools are.

One of the things that we did require was that some type of face covering must be worn at all of our schools. There is — we allow the face coverings

to be taken off in pre-K through grades 3 if a sufficient social distancing takes place in the classrooms. However, if children are moving from room to

room, which there’s very limited movement at the elementary school, or moving within their classroom, then they have to have their mask on.

However, for grades 4 through 12, a face covering is required for all children.

We have limited movement throughout our schools, particularly in grades pre-K through 6. Those classrooms have self-contained teachers in which one

teacher is responsible for the primary instruction of the day. We are making sure that when classes are able to have P.E. and other types of

activities, they are having them where they do not have contact with other groups of students.

Now, in grades 7 through 12, we do have changing among classrooms, however, we have established one-ways in our corridors and in our commons area in an

attempt to help with the traffic flow. Another thing that you asked —

AMANPOUR: And finally, I mean —

CHILDRESS: Go ahead.

AMANPOUR: Sorry. Let me just ask you this, maybe you can incorporate in your next answer. Have you felt any political pressure at all? Obviously,

many people want to see schools reopen for obvious reasons, but some parents, as you know, are worried, teachers are worried. There is a lot of

political pressure from the White House. Have you felt any pressure? Are you confident that in your area, at least, the science is being followed?

CHILDRESS: We have not felt any political pressure here in our area. As I said, we made our decision based on what we expected and what we had been

planning along with community input. We looked at the guidelines for the Centers for Disease Control, the Mississippi State Department of Health

along with the American Academy of Pediatrics, and we incorporated all of those guidelines into our reopening plan to try to address anything and

everything that we needed to create a safe learning environment.

I think one of the important things to be considered is that communities do need to have a voice in what takes place in whether or not their schools

reopen or not.

AMANPOUR: Superintendent Childress, thank you very much for joining us from Mississippi.

Now, Arne Duncan was secretary of education under President Barack Obama. He says, lack of leadership from Washington and a proper national

coordination plan is proving to be devastating. And he’s now going to join us.

Welcome to the program, Arne Duncan.

ARNE DUNCAN, FORMER U.S. SECRETARY OF EDUCATION: Good to see you again. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Let me ask you. Let me start by asking you, you just heard the – – yes, you too. And it’s going to be good to get your expertise on this, on the big, sort of, picture. You just heard the superintendent on lay out

quite a detailed plan about how different kids and different ages are being, you know, given the rules to how to behave in the school. What do

you make of that? And given also that there are some infections already there.

DUNCAN: Well, obviously we have 15,000 school districts across our country, and the fact that every superintendent now has to become a public

health official trying to navigate this for themselves, many are doing testing, trying to do contact tracing, thinking about how you deliver food,

thinking about transportation, how you keep your buildings clean, and yes, most importantly, how do we educate kids, we’re asking way, way, way too

much of our superintendents and the fact that we have not come up with a comprehensive way to do this thoughtfully, the fact that on average over

the past week, we’re having a thousand deaths per day here in the United States.

We simply have not done in March and April and May and June and July what we needed to do so that we could have an easy and smooth and clean opening

to school for our children now in August and September.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me just run through a couple of stats. An Indiana middle school closed after a positive test on day one, and that absolutely

sort of mind-boggled the officials, that how could there be a positive test on day one, they said. Georgia’s largest school district barred 260

employees from working after they either tested positive or, in fact, were exposed.

Now, school has just started. And as you know, senior pediatrician and virologist, Peter Hotez, has said, this push to open schools is guaranteed

to fail. Do you think it was guaranteed to fail or was it always going to be something that had to happen, warts and all, and try to — I’m sorry to

use this word — but the whack-a-mole strategy has it’s been going on, you know, right now?

DUNCAN: Let me answer that in two ways. First of all, I absolutely believe school needs to open, but how it opens, that’s the key question. So,

schools can open three ways. They can open all physically in person, they can open all virtually online, or a hybrid of those situations. And

students have lost way too much learning because of COVID, but COVID slide because of summer. So, we can’t delay the start of opening, school needs

but we have to be very, very thoughtful community by community about what is the safest way to bring kids, you know, back into a learning

environment.

The safest way to bring kids into a physical and in-person school building is where you have two weeks of declining cases where you have positivity

rates below 5 percent. In far too many communities across our country, unfortunately, that’s not the case. So, it’s forcing many, many school

districts either to think about a hybrid situation or to start all virtually, all online. And had we done what we needed to do earlier, we

wouldn’t have to be making these very tough decisions, but that’s where we are today.

AMANPOUR: So, the Hotez, pediatrician, the expert virologist said there are 40 states in the United States where schools should not open for face-

to-face classes, as you’ve just pointed out. And Dr. Sanjay Gupta of CNN has said, the solution must be rapid testing, i.e., the tested — the

results are known very rapidly, much more rapidly than they are known right now. Is that, for you, a central aspect of it, the idea of being able to

test?

DUNCAN: Well, that’s the starting point, but that’s just the starting point. So, let me, you know, elaborate a little bit. There is a level of

complexity on this. Yes, you have to be able to test, but those tests have to be accurate, they have to be reliable, you have to be able to get them

back quickly, and then the questions is, what do you do with those?

You have to be — if you have a positive result, you have to be able to contact trace, you have to be able to isolate or quarantine. So, if all

you’re doing is testing and it’s taking too long, or you’re not taking those second and third steps, then you might as well not test at all. So,

there is just a level of detail that we should be doing at scale.

Schools, school districts, school systems, they’re not islands. They don’t exist in a bubble. They just reflect their communities. Where communities

have high level of cases. Of course, schools are going to have a high level of cases. Where communities are safe, as we’ve seen in other countries,

Norway, Denmark, other places, you don’t have that kind of problem.

Where you’re seeing other country struggle, and we should learn from those, places like Israel, where they opened schools too quickly, too fast, that

they had to shut back down. In Australia, I lived in Melbourne for two years, the State of Victoria, as we saw, declare a state of emergency

yesterday because they opened schools and other things too quickly too fast. And the goal here is not to open schools, the goal is to keep schools

open. And the worst thing we could do is try and open schools too fast, have to shut down after a week or two weeks, further traumatize students,

endanger teachers and custodians and bus drivers, principals and our children’s parents.

We have to go slowly, carefully, gradually, phase this in, start with our most vulnerable children, start with our youngest children. And if, it’s a

big if, if we do it right, add more kids overtime. But our country has lacked the discipline to do what we need to do to have a clean and easy

reopening of schools this fall.

AMANPOUR: It’s interesting that you point to those countries overseas, because as you mentioned, some of them really have done it in a way that

they’ve been able to control the situation. But it comes from their original national and coordinated policies from the very beginning. So,

that’s interesting that you point that out.

I want to ask you about kids, whether they’re American kids or kids all over the world. What are the psychological worries that you have about

keeping children out of physical school for this amount of time? What is the science and your experience say about that?

DUNCAN: Yes. Everybody wants to go back to a physical school. Kids want that, my kids want that, teachers want that, all of us as parents want

that, but we could only do that if we’re not endangering their lives or the teachers’ lives, or, you know, parents and grandparents at home. And so, is

there more isolation in a virtual world? Yes. But you can endanger people’s physical safety, so we’re having to make very hard choices here. Why I’m so

angry is we shouldn’t have to make these choices.

Again, had we done what we needed to do at scale for our country over the past couple months, we wouldn’t be putting kids in this really, really bad

situation. So, I’m just pleading with the public here in the United States that for this month of August, can we just, you know, be smart, you know,

wear a mask, socially distance, wash hands, do all the things that we know that will beat down the virus nationally, and more importantly, in our

communities so we don’t put children in that bad situation.

Having said that, I want to say, I’ve been just unbelievably impressed by leadership at the local level, for all the failure of leadership at the

federal level, the local leadership has been extraordinary. Since the pandemic started, I’ve done a weekly call with school superintendents and

nonprofits who are involved in food distribution, and schools just aren’t places of education, they’re social safety nets.

And throughout this entire pandemic, they have given out — they’ve distributed tens of millions of meals every single day to children, to

their families and to the community. We talk about children’s social emotional health, they have pivoted very quickly to Telehealth, social

workers, counselors, therapist, teachers, workers, checking on students literally every single day to help them deal with any past issues they had

and the trauma of going through all of this and parents, you know, losing jobs and, you know, being all of a sudden very, very insecure and scared in

this world.

And so, to see that local leadership thinking about students’ social and emotional health, making sure our children and their families are fed has

been unbelievably inspiring to me. And they’re working together with urgency, with empathy, real humility, making mistakes and learning from

them and that’s what gives me hope at the time of tremendous darkness.

AMANPOUR: And this is a time, also, of uprising on the streets of America and around the world for justice, racial justice, economic justice. And I

wonder what you think of the fact that, you know, many, many parents who have the money might be able to hire private tutors, might be able to

gather together in what’s known as pods and set up their own, sort of, so- called quasi-home schooling. But that’s the parents who have the money and the ability to be able to do that in the space.

Do you worry that inequity and injustice could be prolonged and exacerbated if this is what parents are, you know, forced to do?

AMANPOUR: Absolutely. And obviously, you know, systemic racism is not a new problem here in America. It’s been a problem for 400 years. What this

pandemic has done and the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis has really pulled the scab off that gaping wound, and its slapping people in the face

and forcing them to deal with those inequities.

There are so many different levels, but just one obvious one is that a time when you have to learn virtually having access to computers, to the

internet, to wi-fi is just absolutely essential. And that access, historically, has been very unequal with the haves having access and the

have-nots not having access. And so, districts had worked very hard here in Chicago. They’ve given out 100,000 devices, Boston 30,000. San Antonio,

47,000. Put in wi-fi hot spots. But there are massive inequities. And always, whenever there is a problem, the children of the poor have a harder

time than the children of the wealthy.

And so, my goal, which I’ve been saying consistently, is not to go back to school as it was, not to go back to “normal” because normal didn’t serve

far too many children well enough. And we need to use this opportunity to reimagine school and come back with something that is much more fair and

equitable and just.

When you look about lost learning time because of COVID in the spring and then in the summer, who is going to fall the furthest behind? Of course,

our most marginalized, our most disenfranchised, our most vulnerable kids. So, not only do we need to reopen school, I would like to see a massive

national tutoring program for those children that are — the furthest behind have an opportunity to try and catch up.

So, whether it’s recent college grads, whether it’s retirees, whether we do it physically or virtually or both, we have many children who are going to

come back to school now, this fall, six, seven, eight months behind. We can’t lose them. We have to catch them up. That’s the kind of thinking we

need now to try and take a horrible situation and have some good come from it.

AMANPOUR: Arne Duncan, thank you so much. Former secretary of education.

And my next guest, Megan Rapinoe, is an activist for justice. She’s the global soccer icon, an Olympic gold medalist, a women’s world cup champion,

named best FIFA women’s player of the year in 2019 and she’s a leader on the soccer field and a role model forethought thoughtful political activism

in sports and through sports. And now, she joins the ranks of talk show host with her new HBO series, “Seeing America with Megan Rapinoe.” The next

phase in her personal campaign for women’s rights, civil rights and racial justice. Here’s a clip from the new program.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MEGAN RAPINOE, HOST, “SEEING AMERICA WITH MEGAN RAPINOE”: It is like the what do we do now moment. We’re in the streets, we’re, you know, saying

black lives matter, we’re talking about a new sort of, you know, radical type society, reimagining everything, and then it’s like now we have to

work. Like, now our work begins. So, I feel like it’s almost like, what do we do now? What’s the next thing? That feels more hopeful to me than it has

in the past, I guess. I’m hoping.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And Megan Rapinoe, welcome to the program.

Let me ask you. I mean, I fulsomely described your activism, your campaign for justice, and, you know, you’re hitting this moment in a very visible

and determined way. Is that right? I mean, is that what you want people to know you for now?

RAPINOE: I don’t know really what I want people to know me for, but I believe that we all have a responsibility to make the world a better place.

You know, do what you can with what you have and do as much of it as you can. I, clearly, am very lucky to have a platform, to get to play for the

United States and be able to take on some of these issues.

So, I personally just, you know, find it interesting and this is the stuff that I like to do and talk about, but really, I think at the heart of it, I

think that we can live in a more fair and equitable society. I think that we can have a better life. And I think that we don’t have to live, you

know, particularly with what’s happening right now. I don’t think we have to live in this world. I think it can be better. And so, for me, I tried to

use all the resources or platform or, you know, microphone, if it’s given to me, to do what I can to make the world a better place.

AMANPOUR: What has it been like in lockdown for you? I mean, you haven’t really been able to train. I mean, it’s been difficult for a lot of sports

people. How are you coping with lockdown?

RAPINOE: It is very strange. I think pretty much since I went away to college, I’ve been, like, on a yearly schedule, and I’m 35 years old now.

So, someone can do the math on that. I think very early on, I tried to just take the approach or the attitude of like what can we do. I wasn’t going to

stress out about not being able to train or play games. That obviously wasn’t possible.

So, you know, with technology, you know, with the capacity of the platform that I have, what can we do to, you know, make our voices heard or to help

out in some way? Sometimes it’s providing comedic relief, sometimes it’s speaking up about, you know, the racial injustice and, you know, the

protesters in the streets and supporting them. You know, and now, the TV show, which I’m very lucky to have. But I think it was just like, you know,

nobody could control this moment right now, so how do you make the best of it and just try to stay level-headed through it all.

AMANPOUR: So, that’s interesting because we’re going to play a clip in a second. You have — I mean, the title, as I say, is “Seeing America with

Megan Rapinoe.” In this — at least the first episode, you’re joined by the congresswoman, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the Pulitzer prize-winning

journalist, Nikole Hannah-Jones, of course, behind the 1619 Project, and comedian, Hasan Minhaj. Are they a regular panel for you or what do you —

what did you want to get out of them? What did you get out of them?

RAPINOE: Well, thank you to all three of them. I was very lucky to be able to pull such an incredible panel together. I think what I was trying to get

out and what I’ll continue to try to get out no matter who the guests are, is, A, that we all have a responsibility in whatever way we can, and we can

be most impactful to make the world a better place, to make it a more fair and equitable place.

Obviously, you know, Representative Ocasio-Cortez, she’s in politics, she’s crafting legislators, she’s looking after her district. That’s going to be

the way that she can be most effective. Nikole Hannah-Jones, obviously a journal. Hasan Minhaj is a comedian. So, how do we all our own way affect

the world in a better path? I think sometimes people feel as if — you know, if they’re not a politician or they’re not a full-time activist, then

they feel overwhelmed as if there is nothing for them to do. But I think that there’s something for everyone to do.

So for me, talking to those three who, you know, I said in the show, they’re already on the front lines of making change, the way that — you

know, Hasan is a first generation immigrant — would see the world is something different than the way that I would see the world. And the way

that, you know, Nikole Hannah-Jones gave us, you know, the real history of the United States, I think, makes people think, OK, well, maybe there’s

something here that I’m not seeing that can broaden my perspective and can allow me understand people or the world in a different way. Because,

ultimately, we all need to do this together.

We’re all in this together. We don’t live on silos. We’re a social animal. And it’s going to take everybody working together, hopefully, to bring us

to a better place.

AMANPOUR: Let me just play a clip. This is with Congresswoman Ocasio- Cortez. This is one of the clips we have been given, but, to your point, this is where she’s talking about a possible tipping point moment.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

REP. ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ (D-NY): But, also, the other way, I think, you can think about it is that we are — you know, perhaps we are in the

downfall of the broken way. This was not built to last.

Inequity, injustice is not built to last. It lasts a long time. It could last hundreds of years, but, ultimately, it crumbles into bits.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you have been on the front line of a lot of activism recently.

I just want to know, right now — and you — obviously taking from what Ocasio-Cortez says, that things could change, pay equality, LGBTQ rights,

taking a knee, all of those things that have thrust you and others, but you particularly, into the spotlight.

What makes you the maddest? Where do you see the opportunity for some kind of resolution, or at least progress, now?

RAPINOE: What makes me the maddest? That’s a tough question.

(LAUGHTER)

RAPINOE: I think the — our biggest sin, of course, as a country is chattel slavery.

And our system of white supremacy and racial injustice in this country, I think, of course, it’s going to affect black and brown people. But I think

it’s the rot inside the entire country. It’s the root of all of the injustice.

So that, to me, is the thing that needs to be having the most attention. And I think, as we start to hopefully unfold what that is and to rectify,

whether that’s education reform, or reparations, or housing segregation, school segregation, whatever it may be, it touches every part of our

society.

Hopefully, we can start to see that it’s all sort of interconnected. I think we can’t just single out one thing and say, oh, if there’s gay

rights, then everybody else kind of has their own rights, everything — the idea of intersectionality.

But I think, for our country to move forward, I think you’re seeing it with the rhetoric coming out of the administration, the Trump administration,

and the Republican Party as well. I don’t think all the onus can put on just Trump. The Republican Party is backing him in the exact same way.

They’re just flaming up these racial tensions in our country, and it’s really not benefiting anyone. And, of course, it’s disproportionately

affecting black and brown people.

So, I think that should be the very first and foremost thing that we focus on. But things are interconnected. So, I think we can start to unravel this

in a really widespread way, whether that be through policies as education reform or environmental, racial injustice or whatever it may be.

I think that we can start sort of having a multipronged approach to making our country a better place for everyone.

AMANPOUR: Can I play a little bit of the new Nike ad that you voice that is — it’s really effective. I mean, it has all different personalities

morphing, what if and the rest.

But we have just picked this little clip And I just want you to talk about it afterwards.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

RAPINOE: We know things won’t always go our way.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: And the world’s sporting events are postponed or canceled.

RAPINOE: But whatever it is, we will find a way. And when things aren’t fair, we will come together for change.

LEBRON JAMES, LOS ANGELES LAKERS: We have a responsibility.

RAPINOE: To make this world a better place.

No matter how bad it gets, we will always come back stronger.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you’re in a place now, Megan, that you can do all this, but it has not been that easy for you to mix the sort of politics with your

sports persona.

You have had a lot of pushback in the past. Are you — are you now at a place where you’re just going to steam ahead?

RAPINOE: Oh, yes, absolutely.

I mean, it’s always been easy for me to mix it. Some people just don’t like the cocktail. They’re still getting used to it.

(LAUGHTER)

RAPINOE: So, I find it very easy. I think that our world is very dynamic and everybody in it is very dynamic. And so to do a number of different

things at one time seems normal.

The one thing I love about that ad, you’re bringing, obviously, so many different kind of undertones into it, whether it be the pandemic, or racial

injustice, or the tragic murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and so many others.

But I think what I feel like it’s saying, what I want to say in that is, we — if we do this together, and if we show up in November, and if we hold

the people who are supposed to be representing us accountable, there is a way forward.

We have chosen as a country to live in this kind of society. And we don’t have to choose that anymore. We can choose to take care of each other. We

can choose education. We can choose health care. We can choose to make this world and make our country a more fair and equitable place.

I think sports is a good analogy for that. You get people from all over the country from every different background coming together for a common goal.

And, obviously, when the group comes together like that, you get something that’s more special than you could ever do on your own.

And so I hope people realize that the election coming in November, and with the opportunity we have, I think all of the lies that have been told about

our politics for a long time really are stripped bare. And I hope people see that we do have a choice, and we have a choice who we elect into office

to hold accountable.

Representative Ocasio-Cortez said that we’re not electing our saviors. We’re electing the people who we get to hold accountable, who we get to

work with, and who we think that can help us shape our country into a better place.

And so I hope people feel energized and feel like they not only have a responsibility, but they can be the change-maker in the world in a really

special way.

AMANPOUR: Megan Rapinoe, thank you so much for joining us.

And the program is available now on HBO and HBO Max, which is part of the Warner media family.

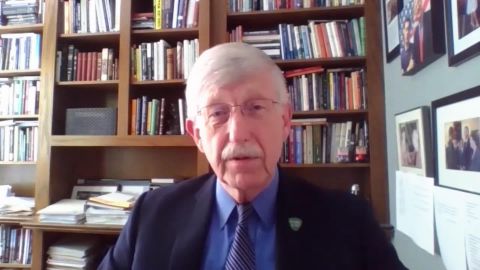

Our next guest has spent 20 years leading public health research in the United States. Dr. Francis Collins is the director of the National

Institutes of Health. And, as such, he is the boss of Anthony Fauci, who’s the nation’s top infectious diseases expert, as you all know.

Here is our Walter Isaacson talking to Dr. Collins about which vaccine trials especially excite him right now, and how he’s relying on his faith

during this pandemic.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane.

And, Dr. Francis Collins, thanks for all you’re doing for the country, and welcome to the show.

DR. FRANCIS COLLINS, DIRECTOR, NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH: Thanks, Walter. It’s great to be with you.

ISAACSON: Let’s talk about Russia, which announced this week that it’s going to roll out a vaccination that has been — passed the safety trials,

but hasn’t gone through those phase three trials to see if it works, whether it’s efficient yet.

Do you think that’s a good idea?

COLLINS: I think that’s a pretty bad idea.

We do phase three trials for two very important reasons. One is to be sure that it really is safe in large numbers of people, that is, to make sure

there’s not one in 1, 000 people who has a bad side effect. You wouldn’t know that from the small phase one and two trials.

But, secondly and really importantly, you do the phase three trial to see if it really works in the real world. It’s fine to say you have a vaccine

that made some antibodies develop, but you want to know whether it prevented disease. There’s no way to do that without doing the hard work of

a phase three trial, with tens of thousands of individuals in a community where the virus is actively spreading, and you can see whether it prevented

them from getting sick.

That’s what we’re doing right now in our vaccine trials in the U.S. And I’m surprised Russia thinks you can skip over that.

ISAACSON: But if the Oxford vaccine, which you have been backing that AstraZeneca is going to do, or the Moderna vaccine, that also have been

proven very safe, why, if somebody like myself says, OK, it looks really safe to me, I don’t know fully whether it’s going to work, but I’m willing

to try it, wouldn’t that help give you more evidence of if it works?

And wouldn’t that be something that I should have the right to do?

COLLINS: I would say, Walter, you should sign up for the trial, where the…

ISAACSON: I want you to know, I have gone to coronaviruspreventionnetwork.org. And I have signed up for the trial.

COLLINS: Excellent.

ISAACSON: But if I don’t get in, I want to know, hey, can I get the vaccine in?

COLLINS: If I were you, I’m not sure I would volunteer out of a trial to learn from the circumstance, because you might be sort of getting yourself

injected with something that ultimately turns out not to be very helpful.

There is this also unlikely outcome, but we need to watch for it in the large-scale trial, which is called vaccine enhancement of disease. And this

has happened with RSV. It’s happened in a couple of instances with rare conditions, but it is unlikely to be the case here. But you want to know,

is there any way that the vaccine kind of revs your immune system down the wrong paths, and then, when you encounter the virus, it actually causes

more severe illness?

I don’t think that’s going to happen here, but we need to know that.

ISAACSON: What do you need to make sure that the clinical trials you’re undergoing are effective and working well?

COLLINS: Well, we need volunteers, and we need a lot of them. In order to really have the appropriate power to determine if the vaccine is working,

we need about 30, 000 people. Half of them will get the vaccine. Half will get a dummy placebo. You won’t be able to tell which one you got, and the

people administering to you won’t know either, because that’s the way we make sure that we can really determine what the vaccine did.

But it will be particularly important that the people who volunteer represent the groups who have been hardest hit with this illness, and that

means older people, people with chronic illnesses, African-Americans, Latinx, because we really want to understand how the vaccine performs in a

circumstance where it’s going to matter the most, which is to protect those vulnerable people from illness.

ISAACSON: One of the other vaccines that you’re backing at the NIH is from Moderna. And it uses an entirely new type of process, which is to not put

it — to send in messenger RNA.

That’s a totally untried, new method, isn’t it?

COLLINS: It has never been used to develop a vaccine that’s gone all the way to FDA licensure, but it is a very appealing approach, because you can

build the vaccine so quickly.

When the sequence of the viral genome from coronavirus was released by Chinese scientists in mid-January, the design of that Moderna vaccine at

our own research center at the NIH took place in about a day-and-a-half.

And just 63 days later, that first phase one trial got under way, where people were being injected with that mRNA, which basically codes for the

same thing. It codes for these proteins. But you stick the RNA into a muscle, and then the muscle goes, oh, this is RNA, I know what to do with

this. It makes the protein for you. And then the immune system sees it.

So, it’s quick, it’s elegant. And we shall see whether it’s actually going to be successful. We will find that out in a few months. By the way, I

should say, there’s another vaccine very similar to that that’s being put forward by Pfizer which is also now in phase three trials using the mRNA

approach.

ISAACSON: So these are in phase three trials. When do you think we’re going to at least start to get information about whether they’re efficient?

COLLINS: Well, a lot will depend on how quickly we can enroll, because we really think we’re going to need tens of thousands of people for each of

these vaccines, and there are several of them. So, you add it up, we’re talking about more than 100, 000 people that we hope will take part.

These vaccines, for the most part, are two doses. So, you get a dose on day one. And then, 28 days later, you get a second dose. And then we start

watching to see what happens after that over the course of the next one or two months to see whether people in fact do still fall ill.

If you got the vaccine, and then you got sick anyway, that’s not a good sign. If you got the placebo and you got sick, but the vaccine people

didn’t, that would say, looks like it’s working.

So, all of this will have to play out over the course of two or three months. I think we got to be careful not to make wild claims about how

early we would actually get a signal here. There will be a group that’s unblinded to the data that will be looking all along the way on the chance

that, A, there’s a safety signal we need to know about, or, B, it looks like it’s working even sooner than expected.

But, mostly, I would guess we will not have an answer until pretty near the end of this year about whether one or more of these vaccines is actually

safe and effective.

ISAACSON: So, if they start detecting that some of these vaccines may be working well, say, in October, November, might you say, OK, let’s just give

it emergency authorization, get it out there?

COLLINS: I don’t want to think that the FDA would do that, unless the data was really compelling.

The worst thing we could do would be to prematurely declare victory, when we don’t have the evidence to do so. And Steve Hahn, who’s the commissioner

of the FDA, has made it very clear that he will not be granting any emergency use authorization, unless the data is compelling, that it’s safe,

and it’s at least 50 percent effective. And, ideally, it should be higher than that.

So, yes, we will have to wait until we reach that threshold. Otherwise, it’s still an experiment.

ISAACSON: How optimistic are you that we’re getting more treatments online now?

COLLINS: We have some real progress to report.

And a lot of that is because of a public-private partnership called ACTIV, which stands for Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and

Vaccines. We do, after all, know that remdesivir, an antiviral, does have benefit for people who are sick with COVID-19 in the hospital.

We know that dexamethasone, a steroid, reduces death rates, particularly for the sickest patients who are in ICUs or on ventilators. But we have a

bunch of other things that are coming along. There are high hopes that convalescent plasma, where you get a plasma donation from somebody who has

survived COVID-19, and infuse that into somebody who’s just gotten the illness, you might speed up their recovery by giving them those antibodies

they haven’t quite made yet themselves.

There are hopes that that will be beneficial. We don’t quite have the evidence to be compelling about that, but we’re working hard on it.

Then right on the heels of that would be something that I am pretty excited about, which is monoclonal antibodies, where, again, you start with

somebody who has survived COVID-19, you identify very powerful antibodies that some of them have that bind tightly to the virus, so-called

neutralizing antibodies.

And then, using biotechnology, you purify those and make them in large, pure quantities as a drug. And those trials are about to start for both

inpatients and outpatients.

ISAACSON: I guess one of the big questions we all have is about schools and reopening.

In the past week, we have had the Centers for Disease Control talk about that Georgia summer camp. We have had a few test cases of schools

reopening. How optimistic are you? And what should schools be doing?

COLLINS: This is going to be so much dependent upon local conditions.

If I were a school board president or a principal trying to sort that out, I’d want to look and see, what is the spread of this virus in my community?

And there are all kinds of metrics you could use. One of the ones that’s turning out to be most useful is looking at people who are getting tested,

and say, what percentage of them are positive?

I mean, think about that. If you have people being tested, and only one 1 percent are positive, that means there’s not a lot of virus out there. If

it’s 15 percent, like it is right now in Florida, that says you have got a really serious problem. The virus is traveling around in a pretty unabated

way. And that might not be the moment to bring people back together in school, particularly as you think about the teachers and the risks they may

be put at.

And there have been suggestions that maybe younger kids don’t get infected and don’t pass this on. I think the data to support that optimistic view is

looking a little shaky, especially after, as you just mentioned, this report about the outbreak in the Georgia camp where kids of all ages

clearly got infected and clearly transmitted it.

So, those things all have to be put into the decision-making for a particular school district to decide what to do.

ISAACSON: Why did testing get so bad and so difficult? It now takes a week here in Louisiana, in New Orleans, to get results back.

COLLINS: We do have a serious testing issue right now with the slow turnaround.

The good news is, we’re doing a lot of testing; 60 million tests now have been in the U.S., which is more than anyplace else. The problem is, the

turnaround has really gotten backed up, as the central laboratories that are doing a lot of this. And main laboratories run by companies like Quest

and LabCorp have just gotten really backed up with demands and there are problems with the supply chain and things like swabs and reagents.

So, what we really need now, Walter, is to have more diversity of testing opportunities, and particularly the kinds of tests that can be done at what

you call the point of care, where you don’t have to get the sample and then ship it off somewhere, but you can get the answer right away in 30 minutes

or less.

Last Friday, we announced awards to no less than seven companies, mostly small businesses, that have some very inventive approaches to doing viral

testing that are ready for a big scale-up opportunity. And we are putting $250 million into that to try to get those out there as early as September,

so that we could have more ways for testing to happen, particularly in high-risk situations like nursing homes or meatpacking plants or schools or

child care centers, where you could get the answer right away.

If you had a nursing home, where the staff walks in, and they get tests before they even go see the first patient, and, if they’re positive, they

get sent home, we might be in a much better place than we are right now.

ISAACSON: Why has coronavirus roared back in the United States more than in Europe or elsewhere?

COLLINS: Well, the sad truth is, we never really drove the virus down to the baseline, the way many countries in Europe did after their very serious

outbreaks.

Basically, we didn’t really follow the CDC’s rules about how to open up carefully. And people were tired of all the things they were asked to do.

And leaders of various states and principalities kind of jumped over steps that were supposed to be taken more carefully following the metrics.

And now we are in a tough spot. Debbie Birx said, we are looking right now at really quite a worrisome situation, where this virus is kind of the

monster that’s all over our country. It’s in cities, but it’s also in rural areas.

And we are going to have a very tough several months ahead. And our best antidote for that, which just seems so obvious, and also seems so

frustrating and boring, is to do those things that we should have been doing more carefully, wear your mask as soon as you leave the house, don’t

congregate, and certainly not in indoor spaces, where you’re crowded all together.

Maintain that six-foot distance. Wash your hands. Everybody has to take responsibility. If you’re not worried about yourself, at least worry about

those that you may infect, if you become the person who transmit to the older person down the street or your grandparents.

This has to be something we all wrap our arms around and say, we’re going to do this. Just like wearing seat belts, it’s good public health. And we

can’t afford to say we’re tired of it, because the virus doesn’t care if you’re tired of it.

ISAACSON: Why do you think so many things about this disease, especially the wearing of masks, but even hydroxychloroquine use or whatever, has

become partisan and politicized?

Is that some lack of respect for science? Or is it just the hyper partisan nature of our society?

COLLINS: Our society certainly is hyperpartisan.

Tony Fauci, who is my wonderful director of infectious disease at NIH, and obviously a very visible spokesperson for what we all need to do together,

we meet every evening by phone just to see what’s going on, and often commiserate about, how is it that we got into such an unfortunate

situation, where something that should be completely nonpolitical somehow has become so?

I think it is a reflection of the fact that, in our country right now, everything is partisan, everything is polarized. That’s sort of the

default. And it doesn’t take much of a tip of the balance one way or the other for people to decide, OK, I have got to add that to my particular

collection of behaviors that define who I am in terms of my politics.

This never should have been there. But, unfortunately, it got there. I will hope we can extricate it and decide at this point, with the president

himself now telling people to wear masks, let’s all do it. And let’s not pretend that we’re somehow exempt because of where we live or what other

kind of aspect of our behavior might be protective.

I have got to say, I’m a person of faith. And it’s troubled me also to see that, in some instances, faith traditions are getting on the wrong side of

this by suggesting that it’s really not appropriate for churches to worry about these things. After all, that’s God’s house.

Well, yes, they are God’s house, but God probably also gave us the opportunity, through science, to learn what is good and safe. And we’re

expected, I think, to pay attention to that if we’re going to be reasonable children of the God’s — the God’s creation.

So, when somebody said to me, as they did a little while ago, I’m not going to wear a mask in my church, Jesus is my vaccine, I was thinking, where

have we come to that we have somehow gotten this mixed up?

So — and the conspiracy theories, of course, don’t help either. That’s another big part.

ISAACSON: You wrote a beautiful book called “The Language of God.” It was about your Christianity, your faith.

As you talk to these religious communities and people of faith, how is your ability to talk to them better because you are such a person of faith?

COLLINS: Well, I don’t know if it’s better, but I do feel a great relationship and warmth to my brothers and sisters who are people of faith

and who are going through terrible struggles, and most of them doing so with great sense of calling to try to do what they can, not necessarily

focusing on, why did this happen, but on, what can I do?

And you can see that happening running food banks, and making masks for people, or figuring out a way to go to the grocery store for an elderly

person down the street, so that they don’t have to take risks. The church is often called upon at times of crisis, and they are responding.

But there’s this fringe there that sometimes seems to have aligned itself in a fashion that’s more political than spiritual. And that hasn’t

necessarily turned out all that well.

I guess, again, as a person of faith, if I have the chance to speak to people in that place, and ask them really to think carefully about what

these messages are, and how we are all called upon not to put others at risk, it does seem like that falls particularly on the shoulders of people

of faith, who have always defined themselves by taking care of those who are vulnerable and less fortunate.

ISAACSON: And how does your faith help you cope with the day-to-day challenges and horrors that you face with this disease?

COLLINS: I will be honest that seeing the suffering and death around us from this pandemic, I am not immune from wondering, why would a loving God

allow such a thing to happen?

And yet, at the same time, scientifically, I know exactly what seems to have happened here, that a virus that was previously living in a bat found

its way into humans. And I can’t really expect God to jump in supernaturally and prevent that. That’s part of the nature of things.

So, I guess, in that regard, I think we are called upon, as believers, always to look at circumstances like this, try to understand what we can

do.

Tom Wright, in a wonderful essay for “TIME” magazine, points out that we’re also-called just to lament and to feel this burden of sorrow for the way in

which things are not perfect. But I also lean upon some of those things that lift me up.

Psalm 46 is a particular favorite. “God is our refuge and strength, an ever-present help in trouble.”

OK, we got trouble here, and we have got an ever-present help. And I’m going to hang on to that.

ISAACSON: Dr. Francis Collins, thank you so much for being with us.

COLLINS: Walter, it’s great to have this conversation with you. We covered a lot of ground.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: A lot of ground, indeed.

And that’s it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me and the show on Twitter. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END