Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, it is commonly said that to understand the events of today, we must turn back the pages. And our next guest begins his story in 1819 and the massacre at Wounded Knee. David Treuer is a Native American writer. He grew up as part of the Ojibwe tribe on the Leech Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota. And he’s now welding memoir with his history and a new book, “The Heartbeat of Wounded Knee”. It’s a timely counter-narrative of life for modern Native Americans and he tells our Walter Isaacson why he believes America is at war with itself.

WALTER ISAACSON: Welcome to the show.

DAVID TREUER, AUTHOR, THE HEARTBEAT OF WOUNDED KNEE: Thank you.

ISAACSON: Tell me about your background.

TREUER: Well, it’s an odd one. You know, my mother is Ojibwe from Leech Lake Reservation and that’s the reservation where I was raised, where I grew up. And my father is an Austrian Holocaust survivor. He’s Jewish, was Jewish. He passed away a couple years ago. And he had a lot of life adventures which are too long for our program and really deserves a book of its own. And wound up on the reservation in the ’50s with his first family. He was teaching high school on the reservation. And for my father, he described it as feeling like he was finally coming home. He said, “I was rejected in Austria and I had to flee for my life. And I was rejected and ridiculed as a small strange foreign Jewish boy in Ohio” where they’d settled during the war. “I’ve been rejected all my life. And when I finally made it to the reservation, I felt like I belonged. I understood the people here and they understood me and we understood each other without having to talk about it.” So for my father, it was a homecoming when he arrived there. And he made a life there. He was such a fascinating guy. He had a kind of attitude in the ’50s that no one else did. When he taught high school, he walked into his classroom at Cass Lake High School with, you know, predominately native students in his class. And he just assumed that his native students were smart, capable, interesting and that they could work hard. He had very high expectations of his students. And that was not the norm. When my mother went back to I think Cass Lake High School for her junior year, her first day in the hallway, the principal passes there and he says, “Well, Peggy, what are you doing here?” She says, “Well, I’m back at school.” He says, “Why?” Because it was — you could legally drop out of school after your sophomore year and most — or many native students did and there’s no expectation that you would continue on and graduate. But my mother wanted to and like she did. Much less go on to nursing school like she did and then on to law school to become the first American-Indian woman judge in the country. So my parents were really fascinating people and really hard working. And what’s interesting is, on one hand, I mean the country did its best to destroy my mother and my mother’s people. And on the other hand, it saved my father’s life. So I grew up in my family knowing the two faces of this country. And I guess implicitly understanding that it’s not one or the other, that our country is always both. It’s at war with itself all the time, between its good intentions and its stated ideals and its practice, and the ways in which it falls short of those ideals. And in my book, I guess, is also an attempt to wed those two disparate strands of the American practice closely together to notice them. And so we can, you know, do better.

ISAACSON: You know your book is titled “Heartbeat at Wounded Knee.” And it seems to echo Dee Brown’s book, you know, “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee”. Tell me why you did that.

TREUER: Well, Dee Brown’s book, “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee”, it was published in 1970. And it’s — it is to date the best selling book about American-Indian history ever published, millions of copies in print. It was hugely influential from the moment it was published. It’s never been out of print. It’s a big book and it sort of squats over the literature in impressive fashion. But I remember reading that book in college and I remember some of the things that he said in the prologue to that book, something like my book is about the Plains Wars or focuses on Plains Wars. I started in 1850 and I ended in 1890 at the massacre at Wounded Knee where — and I’m almost quoting the culture and civilization of the American Indian were destroyed, period. And then he goes on in the prologue to say at the very end, “So if you happen to travel to a modern Indian reservation and see the hopelessness and squalor and poverty, perhaps by reading this book, you will understand why.” And I remember reading that in college and being really, really upset. And this was back in 1990 and ’91 and I thought I’m not dead and my family is not dead and my tribe is certainly not dead and not destroyed. Our culture isn’t destroyed. Our religion isn’t gone. We have all these things. But that’s the common assumption. That is the widely held belief that, for all intents and purposes, American Indian life ended in 1890 at that massacre. And when the frontier was closed in the following year officially by the federal government, and that everything that we’ve been doing since then is not really living, it’s a kind of afterlife of perpetual suffering.

ISAACSON: As an identity and as a minority group, Native Americans can be somewhat invisible. And by that I mean if you walk the street, nobody would say, “Oh, he’s a Native American.” So you can always assimilate or pass or whatever. How does that affect the Native American experience?

TREUER: Well, that’s the thing is that there is no Native American experience and it’s in part what the book is about. You know there are millions of us and so we have millions of different experiences. There are native people like me who grew up on a reservation. There are native people who’ve never been to the reservation. There are native people who grew up in cities and who grew up in the suburbs. There are native people who are educated and those who are not. There are those who practice the religion and those who don’t. There are some who are Christian. There are some who aren’t. There are some who are incredibly stupid and some who are brilliant. There isn’t a native experience. There are just native experiences. And that is in part what I’m trying to show in the Heartbeat of Wounded Knee are the ways in which our lives are nuanced, complicated, layered, and incredibly diverse. So if you asked that question to any number of native guests on this show, that you’d probably get as many different answers to that question.

ISAACSON: So does it make sense then to even think about a Native American identity?

TREUER: I don’t know if it makes any sense to talk about a Native American identity. But I think we can talk about Native American experience in that many of us in aggregate have experienced and contained within us a set of historical experiences and the legacy of certain events in the past. We have shared experience which unites us and makes us different from other groups in the United States certainly. In terms of identity, this is — it’s too varied.

TREUER: What is the urbanization move that happened to many ethnic groups? What has that done to the ability of Native Americans to feel they have some shared experiences?

TREUER: Just about half of all natives live off of reservations. Of those who live off, some live in cities but some live in suburbs, some live in small towns, cities of about 10,000, 20, 30,000 people. So there’s a whole range of off-reservation experience too. It’s not just the reservation and say Los Angeles. But there — you know, but now for the past 70 years or since World War II, we have — we experience a significant migration to cities for the same reasons that African-Americans migrated from the south to urban centers in the north during the Great Migration for economic opportunity, to escape our experience of, I guess what you could also call a kind of Jim Crow existence, in or near reservation communities. And native folk who’ve moved to cities have had a range of different experiences. Some just moved back almost immediately. It didn’t work for them. Some have stayed and made lives, rich ones. And that’s another thing that the book is also about, which is other ways in which, you know, not only are native communities, not just in America, but of it. We have been changed and shaped by this country. But this country has been changed and shaped by us in fundamental ways.

ISAACSON: We’ve just elected the first two Native American women for Congress.

TREUER: Yes, it’s amazing. I’m so happy. The first two Native American women to join Congress. We have Peggy Flanagan in Minnesota who is the highest elected American Indian in an executive position. She was elected as lieutenant governor of Minnesota. It’s an incredible time to be native. And not only how lucky for us but how lucky for their constituents, how lucky for the people of Kansas to have David as their representative. Who better would understand the ways in which the needs of Midwesterners have been ignored, have been pushed to the side, the ways in which the communities in Kansas have been put second to the interests of multinational corporations in the form of agribusiness, for example. Her experience as an American Indian woman and the kinds of structural inequality and disenfranchisements which have visited native communities over the decades and centuries are some of the same kinds of disenfranchisements which are being visited upon Middle America right now. So who better to lead them? Who better to help them?

ISAACSON: So you think the narrative of the American Indian in some ways is part and parcel of all the narratives of America about disenfranchisement, fitting in ethnic groups —

TREUER: Right.

ISAACSON: — and dissimilation?

TREUER: No spoilers. But for me, the thing that I hope people take away from the book more than anything is that if you want to understand America broadly, you have to pay attention to American Indian history. There’s a way in which people read Indians in fiction or nonfiction as a — and the way people read us, the reasons why they read us are kind of like as a liberal act or as an act of atonement for the transgressions of the country, right. They read us as almost like they’re doing community service. And that’s kind. That might be compassionate but it’s not the best reason and the best way to read us or to think about us. If you want to understand how power works, look at the ways in which policy has affected native people. If you want to understand the power in importance in the Constitution of the Supreme Court, look at federal Indian law. I think the author’s name is Charles Wilkinson. And he wrote a book about federal Indian law. And he noted in his book, in the 1970s and ’80s, the Supreme Court heard more cases about federal Indian Law and tribal sovereignty than any other category of law, more than banking, more than immigration, more than capital punishment, more than abortion, The court came to be what it is and worked the way it does and understand itself the way it does by way of thinking about us. So you need to think about us if you want to understand the Supreme Court and how it works. If you want to understand the relationship between the federal government and states, you have to consider the relationship between the federal government states and sovereign Indian nations. Because it was in that three-way battle in Georgia, in the early 19th century in what became known as the Marshall Trilogy, this trilogy is Supreme Court decisions about Indian removal. You have to know that history to understand the beginning of the battle between state and federal power and Indians’ place in that battle. So that pay attention to us.

ISAACSON: The narrative of America really does begin with the indigenous people.

TREUER: Yes, the first act of, you know, of the colonists to protest the British was not just to dump tea in Boston Harbor. They dressed up as Mohawk Indians, in face paint and buckskin and then dumped the tea in Boston Harbor.

ISAACSON: David, thank you so much.

TREUER: Thank you so much. Appreciate it.

About This Episode EXPAND

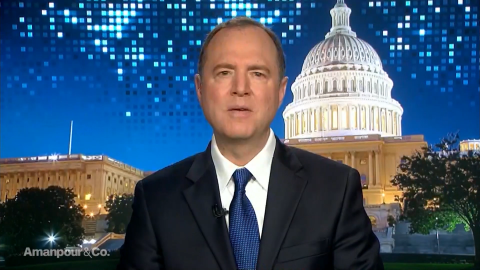

Christiane Amanpour speaks with U.S. Rep. Adam Schiff and Colombian President Iván Duque about the political crisis in Venezuela. Walter Isaacson interviews author David Treuer about why he believes America is at war with itself.

LEARN MORE