Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, coronavirus numbers are surging around the world, and especially in the United States, which remains the worst-hit country. New cases are topping 100,000 now for the ninth straight day. Record numbers are entering hospitals across the nation for the second day in a row. Epidemiologist Michael Osterholm is an infectious disease and public health expert. And he is now also on president-elect Biden’s COVID Task Force. Here he is talking to our Walter Isaacson about what he thinks should be done to build community trust in the eventual vaccines.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane and Dr. Osterholm, welcome to the show.

DR. MICHAEL OSTERHOLM, EPIDEMIOLOGIST, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA: Thank you very much.

ISAACSON: We’ve seen some good news about a potential Pfizer vaccine. We know that Moderna is doing a very similar one, and also one from Oxford and AstraZeneca, all of which may come before the FDA by the end of this month. Do you think if there’s emergency authorization used for some of these vaccines, we’ll be starting to see an effect by January or February.

OSTERHOLM: I think, first of all, we still have to understand what these vaccines can or can’t do. News that we have achieved 90 percent efficacy with the Pfizer vaccine was not really presented with the caveats, I think that are important to consider. Number one, is the — while it’s very good news that in fact, the vaccine demonstrated can work and surely can induce immunity, the challenge is what did that 90 percent mean? Was it 90 percent reduction in fever, coughs and illnesses of mild kinds of symptoms? Or did it prevent 90 percent of deaths, severe illnesses, hospitalizations, and those are two very, very different numbers. And one of the challenges we’ve had with vaccines like this, for example, with influenza, is that often the people who are have this underlying health conditions for serious disease are also the very same people that don’t respond well to the vaccine, meaning they don’t make the same robust immune response that we’ve seen with otherwise healthy individuals. So until we have the data out of this trial to better assess this, I think we have to be a little cautious about what the overall impact of that vaccine will be. But I have no doubt that it can be of some benefit, if not a lot of benefit. And what we’ll be learning, as the FDA reviews these data is that then how can we deploy this? Where should we deploy it first? Should it go to healthcare workers, should go to people with high risk conditions? As I just said, if the high risk conditions individuals don’t respond well, then we might want to rethink where we’re going to look at deploying that vaccine. So, I think we have a lot of information yet to glean before we really have a straight and clear path forward.

ISAACSON: We’re going to see three or four types of vaccines coming online, perhaps in the next few months. They’re like the Pfizer and Moderna, RNA vaccines, which are great because they can be easily made. But they’re bad, because you have to distribute them in extremely cold temperatures. There’s also the Oxford one that AstraZeneca is doing, which is much more easy to distribute and doesn’t need a booster shot. And finally, there’s a deactivated vaccines that they’re already using in China. What type of mix do you think we should end up having?

OSTERHOLM: You know, that’s a pretty straightforward, simple answer, which ones work best? And what I mean by best is, how do they compare in terms of protection, for example, in these risk groups that I just talked about, will one vaccine appear to do better among high risk individuals for severe disease? And so, I think at this point, it’s really all of them are in the running. And they may all perform in a very similar way. In that case, then, you know, it’ll become a matter of ease of administration. How simple is it to get the vaccine into the community. And of course, if you have one dose requirements versus two dose requirements, that becomes a real advantage also. So I think it’s going to be a combination of all these factors coming together to determine, in fact, which vaccines will be prioritized. In the short term, I can say that every vaccine will be used if it’s effective, whether it’s a complicated delivery system, because it requires minus 94 degree refrigeration, whether it’s a two dose vaccine, we’re going to be so short of vaccine in these first months that I have no doubt that all the vaccines will be used. But ultimately, we may one day decide that there is a preferred vaccine for a variety of different protection reasons, ease of use, and potentially even long term immunity.

ISAACSON: You say we’ll be short of this, these vaccines, the government has tried to guarantee pre purchases even get manufacturing going before they’re approved. What else has somebody on the Biden taskforce do you think over the next six months we could be doing to make sure the supply is good?

OSTERHOLM: Well, at this point, I can’t comment at all, obviously on the Biden Task Force since it’s just begun to meet. And clearly those are the kinds of answers that you’ll get out of the task force leadership. But I can say that as a member, one of the things that I surely want to look at very carefully, is each and every step in the process. Number one, in the manufacturing, are there any ways to enhance that that we can make more vaccine in a shorter time period? Number two, how do we move it into the community? And at this point, Operation Warp Speed has a component that is all about moving into the community. And I must say unlike the part of Operation Warp Speed, which has been all about the research, development and manufacturing, which has been remarkable, I can tell you among my public health colleagues, there’s real concerns about the top down approach that’s being taken right now by the government, not recognizing the long standing systems we have in place already for delivering vaccines at the state and local level. I think there’s actually been some challenges trying to facilitate the federal imposed system on what reality. So, that we have to look at carefully and understand how can we best deliver these vaccines. I think the other issue is at this point, and it’s a huge one, you know, a vaccine is just a vaccine, it doesn’t become significant tell us a vaccination, tell us in somebody’s arm. And right now we’re seeing, unfortunately, a lot of resistance to be considering vaccine for COVID-19. And particularly in some communities, such as black, indigenous and community color populations that are just trusting of the federal government of the vaccine. And we got our work cut out for us to get people to actually take the vaccine.

ISAACSON: As a great epidemiologist, what would you do to make sure that people are more trusting of a vaccine?

OSTERHOLM: At this point, first of all, the data are critical, we have to show them, every one of them exactly why we came to the conclusions we did about the level of protection. And the level of safety. Number two is we have to tell them the story. You know, don’t lecture, the public. We in academia sometimes get really good at giving lectures. And what we need to do is tell a story, it needs to be a conversation. And we need to understand why there’s this reluctance or hesitancy among many not to get the vaccine. You know, at this point, my will and a big mouth is not going to get that vaccine used, maybe having big years, and then trying to incorporate that back into what we do will be very important. We need key leaders in our communities to support this, regardless of what your race ethnicity is, who are the leaders in your community that you trust? How will you trust them, why? And we have to work on that now. We don’t have time to go out and create trust of leaders, we have to find the ones that are now and enroll them in our efforts to get the population vaccinated. And that’s something also that is still lacking in terms of what would you do. So I think at this point, I wouldn’t reinvent the wheel. But I surely would, you know, enhance it. You know, what kind of celebrities who can really bring in. You know, what kind of people who are highly trusted in our communities can we bring in. You know, I just participated in a program in Maryland recently, where the University of Maryland has this very interesting and frankly, quite remarkable program bringing in black barbers, men who are cutting men’s hair, day in and day out who are often trusted as sources of good information. And the University of Maryland reaches out to these black barbers and provides them with very important information, they listen to them, they understand the situation and it’s a wonderful example of outreach into a community. We need to look at that same kind of thing. How do we reach the populations out there in systems that already exist?

ISAACSON: One of the other layers of defense we’ll have probably in the next three or four months is rapid testing that’s been, you know, machines that can be done, you know, point at your office, at airports, whatever, some of them using CRISPR, and easy to detect RNA detection facilities. Would that be part of a way to help bring this virus down?

OSTERHOLM: Anytime we can bring in accurate and timely testing, it helps, it surely helps. The problem we’ve had is that many of these rapid detection tests are not that accurate. And we’ve had major problems right here in the field, with both false positives and false negatives, meaning that sometimes when people were infected, we said they weren’t. And sometimes when they weren’t, we said they were. And in some cases, that can be a sizable proportion of the people are misclassified. When that happens, first of all, the tests themselves become suspect in the population. If you’re an individual and you’re found to be positive in one of these rapid tests as it is today, you then have to have a backup of PCR test done. In the meantime you’re in quarantine. And in a sense, when you look at that and what’s happening is we get a test back then three days later to say, oh, by the way, nevermind, you were not really positive. And that is starting to create a lot of mistrust and distrust out here in the community in terms of using these tests. You know, if you want to look at testing as a failure using the same approach, look no further than the White House. I mean the White House, I said way back last May, that using these rapid tests to protect the people at the White House just like giving a squirt guns to the Secret Service and expecting to protect the president against an assassin. You know, the challenges is that these have a relatively low sensitivity. So you may see 20 percent, 30 percent and 40 percent of the people who are really positive test negative. So, I think the key challenge here is, yes, we need rapid test, yes, their deployment could be incredibly helpful. But they’ve got to be accurate. And if they’re not, they actually end up holding us back. Because then people get very reluctant or resistant to testing in general.

ISAACSON: You’re up in Minnesota, in Minnesota and the entire Midwest is getting slammed in the past few weeks. Why is that?

OSTERHOLM: Well, you know, I’ve said all along that this virus is actually spreading in our community is much more like a forest fire, is in a large, large, large forest area. This is not waves. This is like a forest fire that’ll keep burning, it’s looking for human wood to burn anywhere. Sometimes it’ll burn around an area that, you know, you just like we’ve seen real forest fires, where why did that patch of, you know, 6000 acres or 600 acres get spared, we don’t know. But guess what, the embers are still there and it comes back and burns up. By Labor Day, we’re down to 32,000 cases. But now, people were be a combination of pandemic, what I call fatigue, pandemic anger, that area of people who don’t believe this is real. All the behaviors basically were challenged. And now look what’s happening. We’re talking about 125,000 cases a day, just literally eight to nine weeks after we were at 32,000 cases a day. That’s because of people’s behavior.

ISAACSON: With the substantial increase in cases have been people who have again started talking about lockdowns. Explain to me the different ways the word lockdown can be used, what it means and which ways might be most effective.

OSTERHOLM: Yes. Well, first of all, as I say, often, you know, if you interview 50 people and asked what a lockdown is, you’ll get 75 different definitions. OK? I don’t think anybody really knows what they’re talking about with lockdowns. Really, what we’re trying to do is reduce people’s contact with each other. This virus is primarily spread by swapping air with someone. And that’s the point. And so that when we talk about lockdown, we’re talking about how do you keep people to stay at home? How do you keep social events from happening where large numbers of people get together? Even in families, how do you keep people who are part of the family who don’t live at home, come home, bring the virus with them. And it’s all of those. Right now, if you look at the primary means of transmission in this country, we’re looking at bars and restaurants, churches, gymnasiums, community meetings, all the sporting events. All these things are facilitating transmission right now. So, I would come back to the definition that I use, not just in terms of how you employ this, but what do you do to mitigate the bad part of it? In early August, Neel Kashkari, the president of Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, and I wrote an op-ed piece in The New York Times, and said, you know what people are suffering right now, when these “lockdowns” are flattening the curve events occur not just from the virus, but from really some major economic implications. And as the Federal Reserve Bank has noted, we’ve seen a tremendous increase in savings in this country from people because they don’t have places to spend their money. Savings went from 8 percent in March to over 22 percent by mid-August, I understand is even higher now of all income saved. Well, that’s sitting out there waiting for it to be invested somewhere at historically low interest rates. If our government was to borrow that from ourselves and pay ourselves back, and then hold whole everyone who loses a job, small businesses, city, county and state governments, you know, academia as such, if we basically paid for all of that, the data are clear and compelling that we would actually bring this under control much, much quicker in this country. We can then do what the Asian countries are doing with the area of testing, contact tracing, following up quarantine isolation. And we can get back to a more normalized life and surely in improving economy. Look at the economies of the impacted countries in Asia, that would buy us time to get to a vaccine. You know, we’re not asking people to do this forever. We’re living in a COVID year, it’s not like last year, it won’t be, and hopefully not going to be like next year with a vaccine available. Just buy us time so that people don’t have to develop immunity through getting infected and far too many people dying. That’s my idea of a lockdown. Five, six weeks at most, we could drive this down. We need to provide public health agencies with the resources to make sure they then can do the testing, contact tracing. And if I have to test cases at the level of five to 10,000 a day around the country, that’s a heck of a lot easier than testing and following up 150,000 cases a day. That’s what the countries in Asia taught us can be done.

ISAACSON: I know you can talk about what the Biden taskforce is going to do, because he’s not doing it yet. But as a member of that task force, what will you be your top priority when you meet and you say, here’s what I would want to start focusing on?

OSTERHOLM: I think the most important thing if I had to say right now, we need somebody to tell a story. We need an FDR. We need somebody to help people understand what’s coming. You know, Walter, when you think about the fact where, you know, 130, 135,000 cases right now, and we have many intensive care units in this country that overwhelm, healthcare workers, staffing wise or inadequate provide the care we need. And I’m talking to you about having a number much larger than that over 200,000 cases a day. We’re not going to get through that just on brute strength. We’re going to have to get through it in heart and soul. And that’s where we need right now to have that wise, and thoughtful leader who tells us the truth, you know, no sugarcoating, but also doesn’t spare us anything. Tells us what’s going to happen. That’s the credibility we need. That’s what we need right now. So I hope that that’s leadership, we also see, somebody that brings us together for all the right reasons, and gives us hope about where we’re going. This COVID year is not going to last forever. But we need to do what we can to make sure that when it does happen, it has the least impact as possible. If I could see that coming out of this entire effort right now, that would be to me a huge, huge win for our fight against the virus.

ISAACSON: Dr. Osterholm, thank you so much for joining us.

OSTERHOLM: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

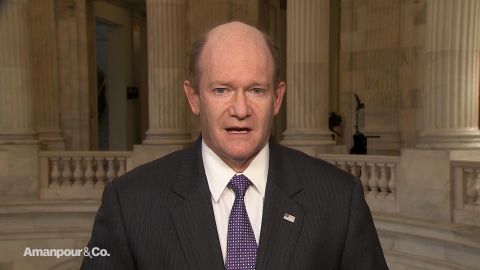

Sen. Chris Coons (D-DE) discusses President Trump’s refusal to concede the election. James Jeffrey discusses the international challenges that lie ahead for President-elect Joe Biden’s administration. Michael Osterholm, a member of Biden’s COVID task force, discusses the leadership the U.S. needs to fight the pandemic. Mary Trump explains how President Trump came to despise the concept of losing.

LEARN MORE