Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Four CEO’s of tech giants worth $5 trillion face a reckoning via Zoom in Washington today. I ask critics inside and outside the industry, should

Congress rein in their massive power?

Then, as the world reckons with the murder of George Floyd, Netflix comedy star, Fary, confronts a self-proclaimed color-blind culture in France.

And later —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CARL ZIMMER, SCIENCE WRITER, NEW YORK TIMES: It’s conceivable, and I say conceivable, that AstraZeneca might be making emergency authorized supplies

of the vaccine in October.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Vaccine tracker, Carl Zimmer, updates us on the state of play in the unprecedented global race for a coronavirus cure.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

The explosive growth of the tech industry is a great American success story. Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google create hundreds of thousands of

jobs and rake in trillions of dollars around the world. But today, for the first time, tech titans are zooming together with Congress, which is asking

is big tech just too big? David Cicilline, chair of the House Antitrust Subcommittee, laid out his concerns about their overwhelming power.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

REP. DAVID CICILLINE (D-RI): Their ability to dictate terms, call the shots, upend entire sectors and inspire fear represent the powers of a

private government. Our founders would not bow before a king, nor should we bow before the emperors of online economy.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And are these so-called emperors stifling competition, exploiting workers and abusing our most personal data in their pursuit of global

dominance? For their part, the four CEOs, Sundar Pichai of Google, Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Tim Cook of Apple and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, argue

their platforms enhanced competition, driving innovation while also helping small businesses grow.

Still, there hasn’t been an industry reckoning like this since big tobacco bosses were hold on the carpet back in 1994. And today’s blockbuster

hearing could mark the end of unregulated growth for the tech sector.

Shoshana Zuboff, one of the first tenured women professors at Harvard Business School is the author and scholar who predicted decades ago the

enormous impact that computers would have on all of our lives.

Her latest book is “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.” And Tim Bray is a leading software developer who recently resigned a senior post at Amazon

over what he calls a vein of toxicity running through that company culture.

Welcome both of you to the program.

So, Tim, since you, you know, have just resigned from Amazon, let me ask you first — but I want both of you to reflect on what you’ve heard so far

during the hearings and whether this is the reckoning that is intended. Tim, first to you.

TIM BRAY, FORMER AMAZON VICE PRESIDENT: Well, I have to say, I’m glad they’re happening and the opening statements by the ranking — the Congress

people on the committee were mature, grown-up, serious, I thought, and very pleasing. It seems like they’re taking an adult and considerate approach to

this.

A couple things stand out. One is that Microsoft isn’t there. That seems weird to me. The second is, one thing that just stuck out to me is that

Representative Sensenbrenner spoke of America’s consumers and conservatives are consumers too.

And that attitude troubles me a bit. Would I hope that Americans are more than just consumers, they are citizens, is they are creators, they are more

interesting than that. Having said that, I have some optimism the committee hearings will move the needle in a positive direction.

AMANPOUR: So, Shoshana, you’ve been writing about this for a long time and studying it for decades, as we said. Do you share the optimism that it

could move the needle? And I guess, do you share the idea, the question, the fundamental question, that this tech sector is just too big?

SHOSHANA ZUBOFF, AUTHOR, “THE AGE OF SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM”: Well, I’m glad you started off with that introduction from Congressman Cicilline.

When I heard it, I was scribbling down those same words, emperors of the online economy.

So, here’s the good news and the bad news, are they emperors? Yes. They are the emperors of surveillance empires that exercise total control over the

world’s information. Unfortunately, none of that is an overstatement. Where Congressman Cicilline understates is that this is no longer constrained to

the online economy. That might have been a true statement 10 years ago.

Right now, the surveillance economics that has made these once-fledgling start-ups into huge surveillance empires in just 20 years, they are — they

have this surveillance economic logic has gone way beyond the online world, way beyond the tech sector and essentially now is dominating every domain

of the conventional economy to such an extent that these empires have indeed become audacious.

And their long game, as I really believe it to be from all of these years of study, is that they see themselves going head to head with democracy,

undermining and trampling individual rights and creating a society based on such an extreme concentration of knowledge and the unaccountable power that

goes with that knowledge, that it is simply no longer consistent with the aims of a democratic society. That — undertaking that challenge, can we

create a digital future that is safe for democracy? That’s the work that begins today, but it will not end today.

AMANPOUR: So, that is a very dramatic and clearly framed argument against the size and the power of these tech — the big tech four. Tim Bray, you

recently, as I said, resigned, you’ve written an op-ed about it, you’ve been interviewed about it. You called it a toxic culture running through

Amazon.

What is the fundamental fear that you have? I mean, colliding with democracy, undermining, you know, the system. Do you think — do you agree

that it’s that toxic, and do you think there’s a hope in heck that this antitrust issue can be brought? In other words, can they be broken up?

BRAY: Well, I would certainly hope so. The classic pattern in antitrust is that some companies stumbles into a source of extreme profit. For example,

in Google’s case it’s web search advertising, which is insanely profitable, and then uses that fountain of cash to invade multiple other sectors and

impose unfair competition on anybody else trying to be in that sector.

Another consequence of this is such companies grow very, very large, and as they grow large, their voice grows louder and the amount of power they

exercise in the hallways of Washington, where we’re watching that hearing, becomes unreasonable. And I think — you know, my particular issue is with

Amazon but I think the notion that there is a completely unreasonable imbalance of wealth and power, not just in the big tech sector but across

the economy, is approaching emergency status.

People feel like, you know, they don’t count because people like — the people who are on display in the committee hearing today are occupying more

and more and more of the atmosphere. Big — too big is just a problem at one point, and when you have concentrated ownership of highly profitable

businesses, free markets can’t possibly work properly.

So, yes, something has to be done and I think it’s perfectly possible to take a reasonably simple legislative approach to stamp out some of the

problems that exist today.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you specifically about your issue, you resigned over the way some workers were treated and fired because of complaining about

certain conditions. And, again, we see even as these hearings are under way, Amazon is in talks with supermarkets or trying to sort of, you know,

get into the supermarket business here in the U.K. by offering free grocery deliveries and things like that. It’s still competing in — as it’s

undergoing these hearings. Just quickly about what is the specific issue that you have with Amazon and why you resigned.

BRAY: Well, the specific issue I had was that there was a debate going on as to whether Amazon was taking adequately good care of the warehouse

workers during the time of COVID, and a reasonable debate to have, and there were a certain number of activists inside the company who were

arguing that, no, Amazon wasn’t. And Amazon responded to that by firing them, which struck me as unethical and unacceptable and also not very

smart. And for that reason, I left.

AMANPOUR: Shoshana, let me just turn to you and just summarize some of the main bullet points of the sort of accusations or the problems that Congress

says it has with these companies.

So, Facebook and Google, or Alphabet, the parent company, accusations that they have grown into dominant monopolies, Facebook on social media, Google

online search, as you mentioned, by squeezing out or buying up their rivals. Apple and Amazon, as we briefly touched on, Jeff Bezos and Tim

Cook, will face a similar line of questioning, whether they’re abusing the enormous power they have as gatekeepers of their marketplaces.

So, they’re distinct cases, four distinct companies. Are there remedies or what are the remedies that you see, Shoshana, that can apply to each one of

them?

ZUBOFF: Well, Christiane, let me just squinch in a little message to Tim. Go, Tim. I’m really proud of Tim and the integrity of his decision, and I

suspect there are going to be many more people like Tim who find the moral gap between how these operations work and what democracy requires. That gap

is just going to become intolerable.

As far as how do antitrust, the tools that antitrust lawyers and lawmakers have to address the harms in these companies, that to me is a matter of

some concern. Right in the opening statements, we heard Congressman Cicilline go after the fact that the companies are surveying, they’re

taking our data.

In fact, these companies have become trillion-dollar empires because they steal our private experience. They turn it into data. They analyze it. They

produce it. They sell it. That is what accounts for the lion’s share of their massive market capitalization. This is a fundamental, illegitimacy at

the bedrock of the business model of these companies.

And if we break them up, let’s say we are able to, you know, pull back out Instagram and WhatsApp from Facebook, let’s say we’re able to shave off

some of those subsidiaries of Alphabet, let’s say we’re able to break up AWS, Amazon’s cloud business and its retail business, the fact of the

matter is, Christiane, that simply breaking them up is not going to address the toxic surveillance, pervasive surveillance that is produced by these

companies and the way in which it undermines democracies, nor is it going to address the really dangerous and unjust employment practices that Tim is

responding to. Not only in the warehouses of Amazon but really across these companies.

We’ve seen Google employees be fired for their protests. We’ve seen Facebook employees be separated for their dissent and their protests. And

so, these are the deeper issues. Simple way to think about it, when you think about antitrust, you think about the size of a company breaking it

up, monopoly.

That’s the container, that’s the box, the size. Most of the things we’re talking about and many of the things that the congressmen spoke to their

introduction are not about the container, they’re about the contents of the container, the methods, the mechanisms, the policies, the actual way these

companies make money.

And unless we go in there and break up their ability to corner data flows of human-generated information, their ability to corner, to own the

infrastructures, the machines, all of the data centers, the servers, the undersea cables, they own all of this.

And thirdly, they essentially have a law on the vast majority of professionals who exist on planet earth right now who are specialists in

data science and behavioral research, who make the A.I. go. They know how to turn all of those data flows into something meaningful and monetizable.

These four companies have a lock on all of this infrastructure and personnel and data flows. Breaking them up is not going to disturb that.

We’ve got to get inside the box and understand these are unique 21st century challenges that will not be fixed by 20th century law.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s take this big example of Facebook. Let me ask you, Tim, Shoshana says it won’t be fixed by the 21st century laws. So, how will it

be fixed? But let me just put you this, obviously Facebook, some 3 billion people use Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, which are all owned by Facebook,

or Messenger, at least once a month.

That’s obviously bigger than any religion. It’s the principal source for so many people and, you know, bigger than the combined population of the U.S.

and China. It’s huge, huge, huge, the power.

And, you know, Mark Zuckerberg, Zuckerberg has been sort of the boogie boy of a lot of criticism over Facebook, what many people, including Congress

and all sorts of other investigations, says something of a maligned influence in many, many, many domains. He obviously pushes back.

You know, do you — what is your — what would be your solution to rein in not just the surveillance capital of a Facebook but the complete and total

dominance?

BRAY: Well, let’s ask ourselves why they’re engaging in surveillance capitalism and applying an all technologies and so on to using it,

artificial intelligence technologies? And the answer sadly is to be more effective at selling ads. And One of the monopolies that most strongly

concerns me is the joint duopoly that Google and Facebook have over the advertising technology and advertising marketplace.

This is immediately, directly and seriously damaging our intellectual landscape because of the many ad-supported publications that are going out

of business because Google and Facebook have figured out how to be so effective at accumulating data and using it to sell ads, that, you know, if

you have a really interesting site directed at some particular interest, you’re probably not going to be able to pay the rent by selling ads. This

is terribly damaging and it needs to be fixed.

And on this particular case, I agree with Shoshana, you know, breaking them up isn’t enough. We need some radical reforms of advertising technology. I

don’t want to get all geeky here, but there are things called cookies and third-parties and so on, and they are being egregiously horribly abused at

the moment in a way that’s very destructive to our society.

And yes, once — I still think we should break the companies up. But once we’ve done that, we need to get in there and, in particular, do radical

reforms of the advertising marketplace.

AMANPOUR: So, just to drill down a little bit more, obviously Facebook is, you know, very concerning because of its power and what other

investigations have said, you know, the power to disrupt elections inspires sort of, you know, sometimes deadly hate campaigns and places, whether

it’s, I don’t know, Myanmar, India and the like.

And by the way, as you know better than I do, Facebook and Google are pouring billions right now today into India, where they think they’ll have

another, you know, several hundred million consumers. But here’s what was written about, you know, how it distorts issues like Black Lives Matter

here in “The New York Times,” social media once functioned as a tool for the oppressed, in Tahrir Square, in Cairo, Ferguson, Missouri, Baltimore,

activists used Twitter and Facebook to organize demonstrations and get their messages out. In recent years a right-wing reactionary movement

that’s turned the tie.

Now, some of the loudest and most established voices on these platforms belong to conservative commentators and paid provocateurs whose aim is

mocking and subverting social justice movements. The result is a distorted view of the world that is at odds with actual public sentiment. And, you

know, the majority of — for instance, the majority of Americans say they support the Black Lives Matter Movement.

So, Shoshana, you know, like you have already seen some and you mentioned it, one of the representatives on this panel is already complaining that,

you know, it’s actually — you know, they’re making it political, like their side or the conservative side is being unfairly targeted. How do you

even get to, you know, a real-world regulation of this if it’s all mixed up in political sort of victimhood?

ZUBOFF: Well, these are political questions, there’s no doubt about that. But the — there’s so much confusion, Christiane, about what is cause and

what is effect. And so, this is something Tim was starting to get at.

When we talk about disinformation or we talk about, you know, the amplification of hate and incendiary messaging, this is an effect, this is

not a cause. It’s not a thing in itself. What is it an effect of? It’s an effect of an economic logic that wants to maximize data flows through the

supply chains of these empires.

So, every single interface that you have with the internet, whether it’s your smartphone or you pass a sensor when you walk through the park or the

camera that’s in the cafe where you’re having a cappuccino or the stuff that you’ve bought because you didn’t really know what it was up to that

you put all over your house, all of these things now are interfaces for the supply chains that take from your experience, turn it into data, and drive

it into the A.I.s of these companies.

So, what they absolutely have to do is they have to maximize those flows. A.I. needs a lot of data. And so, every algorithm that works inside of

these operations is there to maximize what they euphemistically call engagement to make it sticky so that you go back and you do more and you

spend more time and you press more keys, or you use it to go to other sites or you use it even to change what you do in your offline behavior to join a

group, to go to a meeting.

Now, all of that is — every single thing that you do in relation to these interfaces is driving data, and what happens is that if you run into

something that’s really, you know, provocative, it’s like you’re driving down the highway, you pass a beautiful elm tree, you keep driving, you keep

driving down the highway and you pass a car wreck, you slow down and the whole field slows down. That’s what disinformation is. That’s what hate

speech is. People slow down. They engage more. They are drawn to it. That’s the way it works.

And when we say about Facebook or Google or any of these companies, it’s just business, it’s just a business decision, it’s true, it is a business

decision. In the case of Facebook, choosing not to regulate political ads when they’re full of blatant lies, blatant mistruths, that’s a business

decision that also conveniently dovetails with a political decision. Because they’re trying — they have been trying for these last years to be

friends with the Trump administration for one simple reason, the only way that these little companies turned into empires in a brief 20 years, two

decades, is that there has been no body of law to impede them.

Partially, because lawmakers didn’t understand what really goes on inside these companies, but also because lawmakers, starting with 9/11, had a

vested interest in having access to the data that these companies were producing. We have lasted for 20 years kind of democracy being asleep at

the switch, watching these companies become hugely dangerous, threatening empires as Congressman Cicilline implies.

And what’s great about today, whatever this committee accomplishes, what’s great about today is that this is the beginning, not the end, of what

promises to be a long and bitter decade-long struggle over whether or not democracy can reassert control over the digital future. That’s where we are

right now.

AMANPOUR: Shoshana Zuboff, Tim Bray, thank you very, very much indeed and we will keep monitoring this needle and the direction it’s moving in.

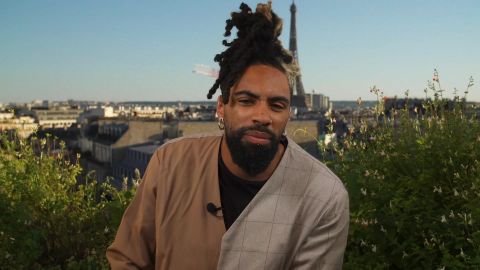

Now, the murder of George Floyd sparked a wave of demonstrations and reflection on race across the whole world, including in France where

protests challenged the culture’s idea of itself as color-blind, where everyone is French and no one is black, brown, Asian or white. Which is

where the comedian, Fary, comes in. He’s become a global phenomenon, star of Netflix’s first French comedy special. He sparked a standup renaissance

at home in Paris. Take a look at this clip from his latest Netflix special “Hexagone.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

FARY, FRENCH COMEDIAN (through translator): I think that I really become French last summer in New York. Because — can I finish? OK. I don’t know

if you’ve been to New York, but when I was over there, it really brought out the Frenchman in me, especially my Parisian side.

It was weird being over there as a French guy, because people you don’t know in the street, like talk to you. For no reason. I’m sorry, but we, the

French, especially us Parisians, admittedly, we need a real reason to talk to someone we don’t know.

Really. To us, it’s very simple, you don’t know me? Don’t talk to me. Don’t. Sometimes, even if you do know me. Sometimes, you’re with a friend

in the street, like, I work with that guys. Look down so he won’t see me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

Fary, welcome to the program now from Paris.

So, before we get into —

FARY, FRENCH COMEDIAN: Hello.

AMANPOUR: — your shows and talk more about them, I just want to ask you what you are — how you are understanding in participating perhaps in some

of the demonstrations, some of the protests and whether do you see any kind of link between racism in the U.S. and in France?

FARY: I think — first of all, I think racism is racism all over the world. That’s the thing about not countries but about white privilege. So, we’re

basically the same. And we did protest here because we also have violence, police violence against racial people.

And so, they often said here in television that U.S. and French it’s very different but it’s the same thing, because, you know, there’s also some

violence by police officers because you’re black. And we had Adama Traore who died exactly the same way George Floyd died, but it was like four years

ago and nobody goes to jail until today. So, I think that’s a global issue and it’s about rethink the way we are, about the way we look.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you because you’ve got a lot of these specials which are creating hits and causing — you know, really popular around the

world. In “Fary Is the New Black,” as one of them is called, you say there are words that French people are scared of. You give an example of white

people being scared to say the word noir, which is black in French, obviously. They say black in English instead.

FARY: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: And as we know, in 2018, your national assembly removed the word race from the first article of its constitution. Can you explain to an

audience why the system is so wary, so reluctant to talk about black, brown, white, you know, Asian? Everybody’s meant to be just French in

France.

FARY: That’s a French culture. It’s (INAUDIBLE) because they think we should act and be the same way, and also, I think they’re afraid about

saying those words because behind those words, there’s issues and subjects about it. If we say black like the French word, that’s a big word to them

because it was, back then, an insult. When you say someone is black, it was something insulting.

And so, they have to rethink and — they have to tell the story again because we — the story they told us, that’s not the story we should listen

to when we are a child. And I think that’s a big issue for them. Because black, it’s — when they say they exist, they’re a community, that’s a

threat for us, for everyone in France because we want to see French as just one people.

And there’s two ways of thinking, that they think it’s opposite, but it’s not. We can have community and we can have people who act like just one

people. So, they think if we have a community, it’s something dangerous, which I think it’s wrong.

AMANPOUR: You know, that’s really interesting actually because everybody wants to claim identity. And, you know, some people say that if you just

talk about being color-blind, you don’t value and you don’t see different identities. And I think that’s what you’re saying right now about your own

communities.

Last year, you caused quite a stir when you greeted the audience at the Moliere theater awards, which is like the Tonys in America.

You said: “Hello, white people.”

And on national radio, you have said France is not anti-racist. You said, you know, “Tell the truth, I was born here,” but you’re still terrified.

And you have gone viral with those clips online.

What is your particular experience? What is the effect — despite the universalism that France adheres to, what is the effect on your real life

and your colleagues and friends’ real life?

FARY: I think, here in France, I’m still a young comedian, and I think that’s also because of my skin color.

And I think that’s what I was saying at the Moliere. I think white people is also a community. And they don’t talk about it. It’s like there is the

normal way and there’s the others. And that’s what I wanted to say when I came and said, “Hello, white people.”

It’s like, we see you doing your stuff just between you. So I think if — that’s something I don’t say often, but I still think, if I wasn’t black, I

would be treated in another way.

That’s — we were talking about this. When you asked for an interview, you said, you wanted to talk about the amazing career. That’s the words we

read, the amazing career I had. And I was very surprised, because that’s someone from another country who is just seeing that I have a career.

And here in France, I’m still seen like a young comedian. And I did a lot of things. So, that’s my way of experimenting. But I think people in their

lives, in real lives, I think I have not a real life, because I’m an artist, but, yes, they have struggled to just go forward in their lives,

because they are seeing, like, just a black one, before being a people.

So, whenever you want a flag, whenever you want a job, it’s way harder than everyone else. And that’s the true thing. And people don’t want to see

that. People don’t want to see that we need people that looks like us, so we can see and say and think that we can do other things than rappers or

soccer players or selling drugs.

That’s something we need. And I don’t see young black people who want to be lawyer or doctors. And that’s a shame.

AMANPOUR: You know, it’s really poignant, what you said there. We should be looked at as people who are not just X, Y or Z.

But you know that, obviously, in 2005, there were riots after two young boys were killed when they ran away from police and they were executed. And

then a few years later, and, twice, we have had, you know, majority black, your national football team winning in ’98, and I guess whenever it was,

2018 or whatever.

FARY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And Zidane, who was so famous, and then Kylian Mbappe in the latest World Cup.

FARY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And the whole world comes together to celebrate that.

Is there a — do you feel there’s sort of a — I don’t know. Is it real? Is it slightly hypocritical? How do you feel about that?

FARY: No, because soccer is like — it’s the same thing than rap. It’s — we can do that. That’s not a problem for them. That’s not a danger.

So, they can accept the national team is — there is black people in it, because we win. So, obviously, that’s something acceptable. But it’s like I

just said. Yes, people, they don’t want to see us — we don’t see us as something — I’m not saying soccer player is not a good thing, but

something higher than that.

And that’s — when we go and protest about police officer, the president said that there’s no discussion, because they use the word (SPEAKING

FRENCH). That’s like we’re a kind of power, like a secret power.

And that’s not even a discussion with the police officers, because they — after the protesting, they started to protest, the police officers, like if

they were the victim. And people are the victim all day long.

Yes.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

FARY: They can protest for something. That is true that everybody sees.

And that’s a way of thinking in police here in France, because they see black people and Arab people like a threat.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

FARY: And that’s the way they talk. There’s not — when we win the world championship, that’s just an event. That’s just a party.

There’s just like the new eve. OK, that’s not real life. That’s like a movie.

AMANPOUR: New Year’s Eve, yes.

FARY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I hear you.

Let me play another one of your clips from your — from the program in June. It’s about called “Facies.” And it’s about names and faces.

I just want to — and it’s sort of about what you’re talking about now.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

FARY (through translator): So, let’s say I’m changing my first name. Would it make you look past the fact that I’m not as fair-skinned as other names

Like, if I get a whiter French name, what’s the idea? That I’ll whiten over time? Oh, sure, you don’t even see color. You have a friend of a friend who

is even blacker than an Arab. Sorry.

If I was Asian and I changed my name, would that be easier for you to pronounce than rice paddy? What if I move somewhere else? Do I have to

change again? Is there like a clever bland name that can bypass your anger?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Fary, you said rice paddy. It refers to a French politician who calls his aide rice paddy.

I want you to know. Your comedy is very sharp. It’s very pointed. Do you have hope that this moment might change certain things, even in

universalist France?

FARY: I don’t think I will see it. I think maybe our child’s child, maybe they will see it.

But I don’t have good hope about it, because people don’t even — the president — don’t even see it as a subject, not a topic for them, because

it’s like we always are playing as victim. We are not. And we are victims.

I am not, but I’m representing victims. And they don’t think that’s a real subject, because they don’t talk about, let’s remove the bad police

officer, let’s change the way police see Arab and black people. Let’s change the way they communicate with people.

They should change all the things. And they’re afraid of it because it’s political. That’s just politics, because they don’t have…

AMANPOUR: Right.

FARY: They — that’s not good for them to change everything because of votes. That’s always the same thing.

AMANPOUR: Well, Fary, thank you so much for bringing your comedy and for your pointed communication, particularly at this time.

FARY: Thank you. That was not that funny, but…

AMANPOUR: And everybody can see your specials on Netflix.

FARY: Thank you so much.

AMANPOUR: Well, it will be, if people get to see the whole — all of them on Netflix and in real life. Thank you.

Now, with coronavirus spiking around the world amid easing lockdowns, all the more need for that coronavirus vaccine. In the global scientific rush,

Russia is the latest, saying its vaccine will soon be approved, although no testing data has been released amid concerns about cutting corners.

Right now, there are more than 165 vaccines in development, and 27 are in human trials.

Carl Zimmer is an award-winning science writer with a weekly column in “The New York Times.”

Here he is breaking down the biology with our Walter Isaacson.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thanks, Christiane.

And, Carl Zimmer, welcome to the show.

CARL ZIMMER, COLUMNIST, “THE NEW YORK TIMES”: Thanks for having me.

ISAACSON: It’s been an amazing past seven days or so for vaccine, which is what we hope will all save us soon.

And with your vaccine tracker in “The New York Times,” you have done a wonderful job tracking them. Why don’t we start with the one that I think

may be furthest along, which is the Oxford vaccine?

Explain to us where that is in phase three trials, and how that actually works. It’s a traditional vaccine.

ZIMMER: So, Oxford University has a vaccine which they are testing out with AstraZeneca, the drugmaker.

And, basically, what it is, is, it’s a virus that delivers a gene into your cells. So, this particular kind of virus only affects chimpanzees. And so

the thinking is that people have not been exposed to this before, so it will be effective for getting into cells.

It can’t replicate, though. These kinds of viral vectors are actually engineered so all they do is just deliver a gene into your cells.

ISAACSON: So, when it delivers a gene into the cell, what does the gene do?

ZIMMER: Well, your cell looks at that gene like any other gene and makes a protein. And this protein happens to be one of the proteins made by the

coronavirus.

And so when your immune system sees it, the hope is it makes lots of antibodies that can then go after the real coronavirus, if you should get

sick.

ISAACSON: Most of the proteins being made by any of these vaccines try to mimic the spike protein, right, on the surface of the coronavirus. Why is

that?

ZIMMER: So, the coronavirus has this sort of halo of proteins, and these are called spike, as you say.

And they use this protein to latch on to cells that in our nose or airway and then invade the cell. So, this seems to be the best target for our

immune system.

So, people who get sick with the coronavirus and then get better, the reason for that is their immune system figures out basically how to go

after that spike protein, so the virus just can’t get into cells in the first place.

ISAACSON: So this Oxford vaccine is in phase three trials. Tell me where it stands, and when we might get results.

ZIMMER: So, this has been going in phase three trials for a couple weeks now, a few weeks now, in several countries such as Brazil.

And it — we will have to wait and see. In a couple of months maybe, we might start hearing about results. It really depends on how many people are

being exposed to the virus in these different countries. They really don’t have that much control over how long it takes before they start to see good

results.

ISAACSON: So, maybe September, maybe October, we will start getting the first set of results?

ZIMMER: It’s conceivable, and I say conceivable, that AstraZeneca might be making emergency authorized supplies of the vaccine in October. That’s

conceivable.

ISAACSON: Wow.

ZIMMER: Could be longer.

ISAACSON: Now, the other two vaccines that in the past week went into phase three trials are one by Moderna, and the other, I think Pfizer is taking

the lead on it, maybe with BioNTech.

And they do something different. They take a piece of messenger RNA and inject it into your cells. Explain to me why that’s different and why it

might be better.

ZIMMER: So, the idea there is that — just to remind everybody of their high school biology, in order to turn a gene into a protein, first, you —

your cell copies your gene into a piece of what’s called messenger RNA.

And that then is used by your cells to make protein. So these researchers at Moderna, at Pfizer have been trying out just making a piece of messenger

RNA, and then getting that into your cells, and then your cells just, boom, make protein out of it.

And so there could be potentially some advantages. For one thing, it’s a lot easier to make a piece of messenger RNA or also a piece of DNA than it

is to take some chimpanzee virus or some other more traditional kind of vaccine, because you’re just like dealing with a code.

As soon as the genome of the coronavirus was put online, you could just say like, OK, there’s the gene for the spike protein, let’s just copy out the

gene or messenger RNA version of it, and let’s get to work.

So, that’s why Moderna was the first vaccine to go to human testing. It’s fast.

ISAACSON: And when do you think they will be getting results?

ZIMMER: Well, Moderna and Pfizer, as you mentioned, just started their phase three trials. So, that could be maybe a couple of months.

Again, there’s a lot of logistics that go into determining when this happens. You have to get 30,000 or people or so into a trial. They will be

doing these in many states in the United States. They will be doing them in other countries as well.

And you have to wait and see just how intense the pandemic is. If you have got people vaccinated in a place where there isn’t a lot of the virus

circulating, it’s going to take a long time to see if you have got an effect.

So, you actually want to go to the places that are most intense, and there you’re going to see a difference quickly between people who are vaccinated

with the real vaccine and who got the placebo.

ISAACSON: I’m in Louisiana, and we’re pretty intense right now. And I signed up for this trial. Was I foolish to do so?

ZIMMER: Oh, no, no. It’s crucial that lots of people volunteer for these trials. Otherwise, we won’t know what works and we can’t move forward.

So — and we can only predict so far like where the vaccine is going to flare up and where it’s going to cool down. That’s one of the really

amazing things about this pandemic, is, it just — it explodes, it dies out, it explodes again.

So, I’m talking to you from Connecticut. We had a horrific problem here in April and May. Now we’re one of the quietest places in the country, for

now. We will see what happens in the fall.

ISAACSON: So we talked about the viral vector, the more traditional vaccine. Talked about messenger RNA. And you can also do it with DNA. It’s

about the same.

Which of them can be manufactured faster and easier and more cheaply if they come out ahead in this race?

ZIMMER: Well, there’s actually a third group of vaccines that really have the big advantage of just a long track record in terms of experience.

That is vaccines that are made out of either a weakened version of the virus you want to vaccinate against or just a killed one. And, really,

that’s actually…

ISAACSON: Sort of like the old polio Salk and Sabin vaccines?

ZIMMER: Tried and true, yes.

And even today, that’s what most vaccines are. There is no licensed messenger RNA vaccine out there for people, none. These — we mentioned the

adenovirus vaccines, like the one that AstraZeneca and University of Oxford have. That is just starting to get approved.

There was one that was approved for Ebola, for example, just like a couple weeks ago. They have been in research for years and years and years, but

the vaccine world moves slowly.

So, if you want to think about, well, what would be the kind of vaccine that you could just make in huge amounts, well, actually inactivated

vaccines, virus vaccines, or weakened ones, those might be the way to go.

ISAACSON: Now, who’s doing those?

ZIMMER: Well, places like China. So, China actually has two inactivated viruses in phase three trials right now.

And so this is really an international story. This is not just the United States doing all the work for everyone. There’s stuff going on in China.

There’s research going on in Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, just — India.

And a lot are them are looking at these more traditional ones. The downside there is that it takes longer to scale up. You want — it takes longer to

make a big batch of these inactivated virus vaccines, because you have to be very careful about it. You can’t rush through it, because you want to

make sure they’re really inactivated.

ISAACSON: The United States, I keep reading, has thrown a billion dollars here, $1.2 billion there, to help vaccine development, like with Moderna,

or many of the others have gotten federal grants.

What do those federal grants do? Do they get paid back? And does that mean we will get the virus more cheaply?

ZIMMER: So, this has been actually kind of a broad trend recently, because vaccines have suffered a lot from what vaccine makers call the valley of

death.

Some scientists do some work on animals. They see that a vaccine has some promise, and they’re like, OK, now we need some heavy hitters to come in

and help us do the clinical trials and do all of the paperwork for licensing and so on. It’s incredibly expensive, and the manufacturing.

And a lot of pharmaceutical companies look at it and they’re like, well, I don’t know. Do we think it’s going to work? Or are we just going to lose a

billion dollars on this? That slows things down.

And so governments and philanthropic organizations for years now have been saying, we need to find ways to speed up this process, for the good of

everyone.

So one idea is for governments to say in advance, OK, look, we don’t know yet if this vaccine is going to work, but, if it does, we’re going to buy a

bunch of them from you. And we will give you some money so that you’re not taking as big a risk on this, and so you’re not going to get destroyed

trying to make a vaccine that will help us all.

ISAACSON: And if it doesn’t work, do we get money back?

ZIMMER: No.

ISAACSON: OK.

(LAUGHTER)

ISAACSON: Now, tell…

ZIMMER: You know, the whole thing doesn’t work. If they say, OK, like, you’re going to spend all — you’re going to put — invest all this and

take all this risk, and if it doesn’t work out, you give us all of this money back, that’s not going to work for a lot of businesses.

ISAACSON: A lot of the pharmaceutical executives were testifying in front of Congress. Some of them said that they would provide the vaccine at cost.

But others, like Moderna, said, no, we’re not going to provide it at cost. And Moderna in particular has been pretty secretive about its approach and

has gotten some pushback from scientists. Is there anything that worries you in their approach?

ZIMMER: Well, I think, in general, we need to be a lot clearer on how everybody is going to get this vaccine.

If each of us has to pay $100 to get a vaccine, we’re not going to get the kind of coverage that we need. And if Moderna says, no, we’re not going to

do this at cost, and won’t even tell us what they’re going to charge for it, we have a problem. And we do especially have a problem, given that the

United States government has been supporting their work.

ISAACSON: Are you worried that there is no process and plan for distributing them, for pricing it, for deciding who gets it?

ZIMMER: I certainly have talked to a lot of vaccine experts who have been in this business for years who are concerned that we’re not reckoning with

the full scale of this challenge.

I mean, there’s a lot of great, stuff again, I should emphasize, in terms of research. The trials are moving forward without sacrificing safety.

That’s really important. Like, we’re going to know about the safety profiles of these vaccines, and in lots of populations.

But you still have that question of, how are we going to do something we have never done before? And we need a plan now. And, honestly, if you look

at, say, where we are with testing, where we’re running out of pipette tips, the most basic equipment for testing, that should make us all very

concerned about whether we have our act together enough in the United States to do something far more ambitious than widespread testing.

Getting vaccines to people as quickly as possible is going to be a much bigger challenge. If we can’t even get the testing right, which we’re not,

then how are we going to get these vaccines right?

ISAACSON: What happens if some people say, I don’t want the vaccine?

ZIMMER: Well, there’s no plans to make it compulsory.

Some people have been wondering, if companies will say, in order to work here, you have to get vaccinated. But, you know, that is an important

issue, because, in order for vaccines — these vaccines to really be effective on a society-wide scale, we need a lot of people to get them,

because, you know, it’s likely that these vaccines are not going to be 100 percent effective.

So, just because you get the vaccine doesn’t necessarily mean you won’t get sick. But if 80 percent, 90 percent of people get the vaccine, then it’s

going to — the virus itself is just going to become a lot rarer, because it’s going to have a much harder time getting around. And that’s good for

everyone.

ISAACSON: At-home tests are being developed by various places, Mammoth Biosciences, Sherlock Biosciences. They like they would be transformative.

They would bring biology into our kitchens and they would let us know instant write where we are. Where do we stand with that, and when can we

expect at-home tests?

ZIMMER: That’s a great question. I wish it would be, like, today. I wish I can hold an at-home test right here on this camera.

It’s very frustrating that we don’t have things yet, because the tests that we’re relying on now use a technology, PCR, which is a great, reliable,

powerful technology, but it’s old. It’s from the ’80s. And it requires a lot of ingredients and a lot of careful fine-tuning and such, so you — you

can’t easily run a PCR in your house on some little device.

But, as you mentioned, these companies, they’re using these new technologies, which you know very well, with CRISPR, where basically you’re

using special molecular probes that can zero in on viral genes in a — maybe even just in a spit sample.

And the preliminary studies on them are promising. And that sort of thing, a cheap, easy — think of it like a home pregnancy kit, but for COVID. That

would change things so much. You just wake up in the morning, take a test, you’re like, oh, my gosh, I have COVID. I’m not going to work. I’m calling

in. I’m calling my doctor.

We would be so much more on top of this pandemic.

ISAACSON: Tell us where your scenario is for how, over the next year, this movie might end?

ZIMMER: I think now and I think ahead to a year from now. I think that we will have much better treatments for people, so people who do get sick are

going to be less likely to die and less likely to suffer lifelong illness.

People will be beginning to get vaccinated, so that will help to drive down rates. But I think we’re still going to be making dealing with the virus

just a part of our everyday life a year from now.

I won’t be shaking hands. I won’t be hugging strangers. I just — it just is something that we’re going to have to be ready to ride through. My big

hope, my big, big hope is that we take this experience and get ready for the next pandemic now, that, if we’re not looking forward, we’re going to

get caught again.

ISAACSON: Carl Zimmer, thank you so much for joining us. Appreciate it.

ZIMMER: Thank you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And, of course, the world is on tenterhooks about developments there.

And, finally, the memorials to George Floyd continue nine weeks since he was killed by police in Minneapolis. His face is lighting up Confederate

monuments across the United States.

The family’s foundation is teaming up with Change.org to create this 3-D hologram, a stunning juxtaposition of black life over the leading defenders

of slavery. The high-tech memorial was projected on Tuesday night over the statue of the Confederate Army commander Robert E. Lee, still standing in

Richmond, Virginia.

And it will travel to four other stops in North Carolina, Georgia, and other states, following the route of the 1961 Freedom Riders, who rode

buses to challenge and desegregate public transport and even dining.

George Floyd’s brother Rodney hopes the artwork will — quote — “be a symbol for change in places where change is needed most.”

That is it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me and the show on Twitter. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END