Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Freezing and trapped, a humanitarian catastrophe grips Syria as the regime’s Russian-back defensive in Idlib takes an even deadlier turn. I

speak to the head of the International Rescue Committee racing to keep civilians alive.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

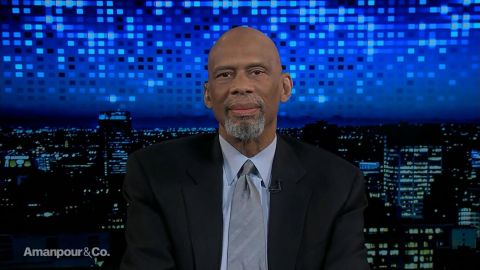

KAREEM ABDUL-JABBAR, BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMER: The American Revolution was fought by many people from many backgrounds.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Black patriots, NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s film on the forgotten black heroes of America’s war of independence.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN, BROADCAST JOURNALIST, CNN: Do I own my face anymore?

HOAN TON-THAT, FOUNDER AND CEO, CLEARVIEW AI: It’s your face, of course you do.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The facial recognition company that could end privacy as we know it.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Hundreds of thousands of Syrians are fleeing for their lives right now as the United Nations warns the biggest humanitarian catastrophe of the nine-

year war is under way. Syria’s Assad regime backed by Russia is accelerating its deadly offensive against Idlib, the last opposition

stronghold where also there are millions of civilians.

The U.N.’s human rights commissioner calls it cruelty beyond belief as children freeze to death in subzero temperatures and families walk for days

on clogged roads with no transport out. Correspondent Arwa Damon has been reporting on this unfolding disaster and of course, some of the images in

this report are upsetting to watch.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ARWA DAMON, CNN SENIOR INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): There is barely enough light to see as we head toward Samia’s (ph) tent in one of

Idlib’s sprawling camps. A couple of nights ago, temperatures dropped well below zero and the family didn’t have enough to burn.

I fed my baby and he went to sleep, Samia (ph) tells us, still in shock. At 6:30, 7:00, the children woke me up screaming. I touched him and he was

icy. The doctors told them he froze to death. Her husband walks out before he breaks down. She doesn’t have a photograph of Abtal Wahab (ph) alive.

Just this image as they say their final good-byes. She can’t forgive herself. She can’t understand how life can be so cruel. Few people here

can.

We have made multiple trips into Idlib Province, none like this. Roads throughout the province are clogged with the traffic of those on the run.

Unending waves. Many have been displaced multiple times before. But this time, it’s different. They feel like no matter what they do, they won’t be

able to outrun the war. These children walked for seven hours in the middle of the night to get away from the bombing near their village, but it’s not

far enough.

They want to leave from here, but they need to try to figure out transport or something, because if they try to walk, it would just be impossible.

Down the road, the (INAUDIBLE) clutch their stuffed animals for the last time. For theirs is a world where toys are not considered essential,

survival is. They don’t cry or complain as they are loaded into the truck.

There is a sense of finality, claustrophobia, compounded by the collective misery of those trapped here, with the regime rapidly closing in and

emptying out entire areas.

Obeya’s (ph) tent is perched on a hilltop, away from the countless other makeshift camps. Our conversation is broken up by warnings from an app he

has on his phone about where the planes are flying and bombing. His elderly mother lies in the corner. She’s been that way ever since they found out

that his brother died in a regime prison. And the regime is getting closer.

This is his brother who was detained in 2012 when he was part of the protests. And then in 2015, they got notification that he was dead. This is

the photograph they got of him dead. Imprisoned.

All I have is this photo, just this memory, he says, haunted by his pain. Even if the regime tried to reconcile, it’s impossible, he swears. You

can’t trust them.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: It is such powerful testimony and things will likely get worse in Idlib as President Assad and his Russian backers have made it clear that

their only goal is total victory. Listen to him on national television.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BASHAR AL-ASSAD, SYRIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): We are fully aware that this liberation does not mean the end of war, nor the collapse of

schemes, nor the demise of terrorism. Nor does it mean that the enemies have surrendered, but it certainly means rubbing their noses in the dirt as

a prelude for complete defeat sooner or later.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Rubbing their noses in the dirt. Well, David Miliband, is head of the International Rescue Committee. It is one of several aid

organizations on the ground desperately trying to save Syrian lives and he’s joining me now from New York.

David Miliband, welcome back to the program.

DAVID MILIBAND, PRESIDENT AND CEO, INTERNATIONAL RESCUE COMMITTEE: Thanks, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: You know, we’ve had you on many times. And each time, you give a very eloquent disposition about what’s happening to the people on the

ground. And even as we speak, there’s a U.N. meeting going on. And where does it bring us? If the world doesn’t act now, this terrible catastrophe

is going to get worse.

MILIBAND: You’re right. What we are seeing from some of the extraordinary journalism by people like Arwa Damon is a political emergency as well as a

humanitarian emergency. The pictures and the stories are absolutely telling of a de-humanization that really shames everyone. But the political

gridlock is also very, very striking. Not just the competence and the inhumanity with which hospitals and people fleeing are being bombed and

shelled, but also the politicians and governments who are turning away to focus on other matters.

I think this really is now a question of fundamental importance for the meaning and purpose of the United Nations. And I would like to see either

secretary general of the U.N. get on a plane and go to Idlib, talk to the people that you have been talking to, that your correspondent has been

talking to, go to Moscow, talk to the Russian backers of the Syrian government, of course, talk to the Turks and then come back to New York and

urge and drive and shame the nations of the United Nations to live up to the most founding elements of the U.N. Charter of 75 years ago.

AMANPOUR: Well, that’s pretty strong coming from you, directly to the secretary general. Why do you think he doesn’t do that? That is within his

remit. It is within his power. Even if he can’t turn on and off a switch, he can bring the moral case to the world and the world’s case to the

backers.

MILIBAND: Well, rail politic is what’s led us to this impasse. It’s important to underline what your correspondent said, which is that, this is

the largest displacement of people since the war began, and that’s nine years of war, 6 million refugees, 8 million internally displaced. Over just

this weekend, 130,000 people driven from their homes with nothing to hold, not even the children’s teddy bears that you referred to in the film.

And the fundamental aspect of the post-war order is that civilians in war should be protected. And I call this an age of impunity because there is no

accountability for those who are literally committing war crimes as we speak.

AMANPOUR: David Miliband, let’s just talk about what’s happening on the ground. So, you’ve mentioned the 100,000 this weekend alone. Since

December, some 900,000. That’s nearly 1 million people trying to get out. We’ve seen these pictures of what we call clogged roads. There are loads of

trucks, but many, many more can’t get on any transport and can’t get out.

What is the actual physical actual reality beyond what we just reported that these men, women and children, and mostly women and children, are

facing now as they flee?

MILIBAND: Well, the physical reality has two differences to what you just said. First of all, they’re not trying to get out. They can’t get out. What

they’re doing is moving west and they’re moving north into a tighter and tighter, more densely populated enclave, pressed up against the Turkish

border. Turkey already has 3.5, 3.7 million refugees from Syria, and it’s saying it will take no more.

The second aspect that’s different but was evident from the film you showed, is how freezing cold it is. People don’t associate the Middle East

with minus 11 degrees centigrade, but that’s the kind of weather conditions that have led to the seven deaths reported of children freezing to death

that have been reported by the United Nations.

So, the clogged roads, yes, but also people fleeing from abandoned houses that are being shelled, fleeing through fields and finding their way to the

“finality,” I think that was your word, of being huddled up against trees, 50,000 people under trees, others in tents with no heating.

Aid trucks are going through the border crossing to Turkey at the rate of about 1,000 a day. But at the U.N. meeting you’ve just referred to, the

coordinator of the U.N. humanitarian effort referred to a $500 million deficit and a need to widen the number of trucks that are getting through

to immediate humanitarian need.

AMANPOUR: Whoa.

MILIBAND: So, the agenda for the secretary general is absolutely clear, it’s a cease fire, which is complicated but necessary and absolutely

justified. Secondly, it’s accountability for the crimes. Thirdly, it’s proper humanitarian help on a scale that is needed given the physical

conditions. And then fourthly, and critically, remember the whole argument over the Syrian government is that they’re rounding up terrorists. But

they’re not. Amidst the 3.5 million people in Idlib Province, there may well be 20,000 to 30,000 people in various terrorist factions, but they are

not the victims of this at the moment, they are actually profiting from it.

AMANPOUR: Let’s take the humanitarian urgency. You mentioned, you know, they need food, they need a huge amount. Well, the head of the World Food

Programme, David Beasley, has been talking to the Europeans about this. This is what he said is urgently needed.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DAVID BEASLEY, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME: For us to feed a Syrian, to support a Syrian in Syria is about 50 cents per day. And that’s

almost double the normal cost because it’s a war zone, logistics cost more in war zones. That same Syrian that may have lived in Damascus, if we’re in

Brussels or Berlin, the humanitarian package is 50 to 100 euros per day.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, he’s, you know, obviously making the case that it’s better and cheaper to be able to immediately send them sustenance. But let me also

ask you, because the second part of what you said is to get a cease fire and hopefully somewhere down the line, some kind of accountability. But a

cease fire, you heard what we ran from Bashar Assad, the president, who believes he’s winning. He said, rub their noses in the dirt. What does that

look like?

MILIBAND: Well, that looks like children freezing, it looks like 250 civilians being killed over the last three months. It means innocent people

losing lives and livelihoods in the most unspeakable way. And so, the human toll is not just some sort of collateral that can be added onto a balance

sheet at the end of this war, it defies the very purpose that is alleged to be behind the battering ram that is being applied to the people of Idlib.

And it’s important for your viewers to remember, many of the people now crowded into Idlib Province have moved from other parts of Syria. That’s

why David Beasley of the World Food Programme referred to someone who was previously in Damascus, in Eastern Ghouta or previously in Daraa, 1.5

million people have been shepherded into Idlib as a result of previous settlements in other parts of the country. And this is all about leverage,

it’s all about pressure.

At the moment, Turkey is facing the conflicting need on the one hand to defend its soldiers, six Turkish soldiers were killed earlier this month,

13 Syrians were then killed in a reprisal. But on the other hand, it’s trying to figure out how to deal with the pressure of more refugees

arriving. And that’s why this is not just a Syrian issue, it’s a Middle Eastern issue, but frankly, it’s also a European issue because Europe has

struggled to deal with the refugee flow in 2015 and 2016, we discussed it at the time, and it’s going to struggle again if it can’t find a way to a

ceasefire that holds the line on the civilian slaughter that’s happening at the moment.

AMANPOUR: And do you expect it to — I mean, the terrible specter that’s just been raised by the president of Turkey is that Turkey could intervene

militarily and, I don’t know, take on the Russians. What is that going to look like? I mean, Turks and Russians fighting there?

MILIBAND: Well, Turkey has intervened. Turkey has already intervened though. Turkey has 13 oversight points in Idlib Province. They are armed

with, I guess, 80 to 100 soldiers, and it’s made very clear both through actions and words that it will fire not on Russians but it will fire on

Syrian troops. Eight to 13 Syrian troops, as I said, were killed.

So, the diplomatic action here is Syria, Russia. Also, vital to see Turkey as part of the equation and Iran. Those four countries have taken

occupation, if you like, of the diplomatic effort. The U.N. mediator, the U.N. special envoy has been pushed to one side. The U.N. has been pushed to

one side and that’s a further reason for the secretary general to reassert the role of the United Nations as the preeminent peace-making body.

Because as long as the Syrian conflict is a matter for Russia, for Syria, for Turkey and for Iran but not for anyone else, you’re not going to get

the kind of settlement that can bring any kind of sustained peace to the country. It’s important to also remind you two aid workers were killed in

the south of Syria earlier today. That shows you that there isn’t a sustainable peace even in areas where the Assad regime has now established

control.

AMANPOUR: You mentioned Russia, you mentioned the U.N. the British ambassador, Karen Pierce, to the U.N. took on the Russians and, you know,

we’ve heard, whether it was Susan Rice or Samantha Power as U.N. ambassadors under Obama, whoever it might be, they’re always trying to

shame the Russians who have the ultimate power there over Assad into doing something. And this is now what Karen Pierce has said in public at the

Security Council. Just take a listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

KAREN PIERCE, U.K. AMBASSADOR TO THE U.N.: The reconstruction of Syria (ph) will be made infinitely harder by the destruction, the wanton

destruction that the Syrian and Russian governments are carrying out now. So, it will be for Russian taxpayers, Mr. President, possibly assisted by

Chinese taxpayers, but it will be for Russian taxpayers to put Syria back together again.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, David Miliband, the humanitarian appeal to Russia didn’t work for the last nine years. Is this going to work?

MILIBAND: Well, obviously the reconstruction of Syria is not the issue at the moment. The issue is to stop the fighting. Obviously, the Europeans

have made absolutely clear they’re not paying a penny until there is an inclusive political settlement.

I also want to remind you that there is a second area of Syria that is not yet under the Assad government’s control and that’s northeast of the

country. There’s 1,000 American troops there and that has been a more stable part of the country. So, it’s obviously the Kurdish part of the

country around Deir ez-Zor, around Hasakah Province as well. And so, you have these two parts of Syria that remain with the control of the

government, that remain a saw (ph) that has to be addressed in a political way, not in a military way.

I want to tell you that there are still at least 300,000 people in Idlib City. We’ve been talking about Idlib as a province. It’s also a city. It’s

a built-up city. No one has a military plan to go street by street through Idlib. And so, I think that the pressure now has to be for a halt to this

senseless bombardment that both sets back any hope of reconstructing Syria, never mind compromises the safety and security of civilians who have

already been twice, three times or four times displaced.

AMANPOUR: You mentioned that other space there, which is kind of significant space occupied by the Syrian Kurds and there are American

troops in the area. You’ve said what you think the U.N. secretary general should do. What should the United States do? What have the president of the

United States do or say to try this affect this?

And remember, you know, very prominently, Syrian exiles went to the president more than a year ago and warned them about Idlib being in the

crosshairs of Assad and this would happen and he promised them to take — you know, to take it seriously and to look into it. What should America be

doing?

MILIBAND: Well, you’re making a really important point, Christiane. This is about geopolitics as well as humanitarian aid. The American troops —

obviously, I lead a humanitarian organization. So, I’m not making military recommendations, but I can report to you that American troops have been

part of a fragile equilibrium in the northeast of Syria that have made it the more stable part of the country over the last nine years.

My plea to the president would be twofold. First of all, to make sure that humanitarian concerns are fully integrated into every military decision

that he takes about the deployment of the 1,000 American troops, 800 to 1,000 troops, who are in the northeast of the country. And secondly, that

he throws diplomatic priority and diplomatic weight behind the resolution of the situation west of the country.

Because without leverage, without priority, without consistent pressure, without linkage between the Syria issue and other concerns that Russia and

America have together, without that kind of leverage, there will be no respite for the people in the northwest of Syria, nor will there be any

kind of sustained stability in the Middle East.

AMANPOUR: David Miliband, thank you so much for yet again bringing —

MILIBAND: Thank you very much.

AMANPOUR: — this forward (ph) at this terrible time. And it is a terrible forgotten war.

And we’re going to turn now to a new documentary that’s shining a light on the forgotten heroes of the American Revolution. “Black Patriots” is NBA

Legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s latest project. The documentary tells the stories of the black revolutionaries who helped establish America but are

often left out of the history books. And Kareem Abdul-Jabbar joins me now from Irvine, California.

Welcome to the program.

KAREEM ABDUL-JABBAR, BASKETBALL HALL OF FAMER: Thank you very much. Nice to be here.

AMANPOUR: You know, I know that you’re a history buff but I’m not sure how many people knew that. I know you’ve written books about this subject to

keep the black participation in the United States front and center as much as you can. What made you do this particular project? It’s really, really

fascinating.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I thought that most people don’t understand why America became what it has become. And there are many reasons for that. And

part of the American Revolution was in the hands of black Americans who made it possible for the American Revolution to succeed. And I think that

we should all understand that, especially black Americans, because they have to understand their stake in our country. This is their country.

AMANPOUR: Yes. At what point did you realize? I mean, what was the thing that triggered you? When did you realize that their historic role was

written out of the books, so to speak?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, just when I thought back to the history books that I had to deal with when I was in grade school and high school, they never

ever dealt with this subject. And all American kids learn about the establishment of our country. It’s part of our civic education. And black

people are — were never included in that recitation of history, and we have to change that.

AMANPOUR: So, we have a few images of some of the black people, as you mentioned, who are profiled in the film. One of them — the first one we

have is Crispus Attucks. Now, he was the man who was thought to have a black father, native American mother, he escaped slavery and was working

around Boston Harbor and he’s widely regarded as the first person killed in the Boston Massacre, which essentially triggered the American Revolution.

Here’s a little clip and then I want to talk about his life and his contribution.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: A group of these black and white dock workers who come together and try to form a public procession to declare their outrage.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: At that point, because he was a run away, the prudent thing for Attucks to do would be to quietly back away and kind of get out

of this fight. But that was not his, I think, character or personality.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Attucks is described as being at the front of this crowd, big guy, and he’s carrying a big club, and some of the British

records would say that he’s brandishing the club, that he’s menacing the British soldiers.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: We know that the British soldiers were harassing them back. And so, it was a back and forth. The British had guns and the British

used them.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, that’s some of the historians who are telling us and showing us some — you know, some of the imagery that has been discovered. But give

us — you know, tell us about the importance of what he did, the significance Attucks.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I think the significance from a historical perspective has to do with the fact that from the very beginning, black Americans had a

stake in what was happening during the revolution because they saw that if the colonies were going to be free, maybe they could be free.

A number of black people in this — in our country were free and posed a direct contradiction to the slaves and other people of color who had to

accept second-class citizenship. So, all of these questions were in the air and were going to be resolved by the end of the revolution.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, you mentioned some were free, but others, for instance, another one who you profile, Peter Salem, he was born into slavery, but he

was freed by his owner, by his master, to serve. And it’s believed that Peter Salem shot a Major Pitcairn who was an officer in the British army at

Bunker Hill. And we have this image up now, this amazing painting, which is at the fighting at Bunker Hill and you believe that Peter Salem is hidden

in the corner there.

What does it tell you, just the fact that you can barely see him? By the way, you have to really squint. What does it tell you about even how these

brave black patriots are even remembered in culture, in art, not to mention history books?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I think that painting points to the marginalization of blacks and other people of color when history is written and retold. That’s

been the problem. The people who write the history seem to want to marginalize or eliminate certain segments of society out of their

contributions. I could name many more contributions that have gone unnoticed or marginalized because of this phenomenon, the people who write

the history books have some crazy ideas.

In Texas, at one point, they tried to refer to slaves as workers, you know, people who came here to work. This is not true. These were enslaved people

who had no choice in this matter. You know, to spin that is put on historical events by school districts and people who write history books is

very important when you talk about the effect that these books have on students.

AMANPOUR: And you say some crazy ideas. Well, you report in the documentary that even at the time there were crazy ideas, or maybe even in

retrospect, you know, there were aspersions casts against blacks for their ability, could they actually fight, were they smart enough to figure out

what to do. I mean, these are quite shocking, these stories that are told in this — you know, in this documentary.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, of course. You know, at some point, people who owned slaves have to justify the fact that they are enslaving people. And at some

point, they say it’s good for them, it teaches them discipline or any other reasons. But usually its financial, slavery enabled certain people to get

rich and have privileges. So, you know, we have to understand what the facts are and then — and point them out and, you know, let the chips fall

where they have to.

AMANPOUR: You know, another one of the people who you profile in this film is a woman called Phillis Wheatley. Now, she was born in West Africa. She

was then sold into slavery at around eight years old and then transported to America. Where she was taught by her slave owners to read, she began to

write poems and at 20, she’s the first African-American, first enslaved person and only third woman to publish a book of poems. But significantly,

she writes a letter to George Washington. Tell me about that and why that is important.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I think Phillis’s letter to George Washington really showed George Washington that people that he looked down upon as being

second-class citizens and not as human as he was really were human and they had human feelings equal to and every bit as valuable as the feelings of

Europeans. So, you know, that was something that must have gotten through to George Washington, you know, and had him understand that he did have a

quandary.

The whole idea of getting black slaves to join the army was really embraced by both the revolutionary side and the British side because, if that

happened, their armies would have been able to deal with the manpower shortages that were chronic on both sides. So, you know, there’s a method

to a lot of the madness that we see going on during this time.

AMANPOUR: Well, this is really important, because many of the black fighters, and there’s one by the name of James Armistead Lafayette, many

who played a very significant role at the end, you know, basically forced the British surrender, but many of them believed that they would be freed,

many of them thought that if they fought, they would win their freedom. And it didn’t come to pass.

And yet, the British did promise them freedom and you report that four times as many North American enslaved black people fought for the British

than for the colonies.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Yes, that’s true. And when the hostilities were over, many blacks left the colonies and were able to enjoy freedom outside of the

colonies. Whereas the ones that took the offer from the United States side found that the promises were not going to be kept and they had to be

returned to slavery.

The person that you mentioned, James Armistead, he had been a spy and could not gain his freedom because he did not fight. But De Camp de Lafayette

petitioned the Virginia legislature to free James Armistead. And they did.

And James Armistead adapted Lafayette’s last name, in appreciation of the effort that he made to gain his freedom.

AMANPOUR: It’s really an extraordinary thing. And it’s a great reminder to all of us.

And I want to ask you now about the current war. Let’s talk about the current political electoral war that’s going on in the United States.

Obviously, all the candidates are trying to court the African-American vote. We’re talking about the Democrats now, and, of course, President

Trump.

You have said that the Democrats should adopt sports tactics in order to fight this fight well. What do you mean exactly? What do you see going on

in this race?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, that the whole idea is about teamwork.

We have to work together to achieve the goals. And we have to have clearly defined goals. So, any team that comes together to achieve something has to

really have a good plan that everybody agrees on and is willing to work hard to implement. So, I hope that’s what happens for our side.

AMANPOUR: And what do you think about the chances of a Joe Biden, who is relying on the African-American turnout in the next primary, probably in

the caucus, too, Bloomberg, who is also surging in the polls? Do you have any particular thing to say about either of them?

ABDUL-JABBAR: No, I think we have to find out exactly what their positions are. And that isn’t really clear yet. We really haven’t narrowed the

choices down enough to where we have a clear and — a clearly discernible choice to make between clear positions on whatever side you’re trying to

support.

So we will get to that point, just because the process demands that. And I think that’s the good part about our electoral process. People have to go

out and state what their positions are and see how much support that they actually are going to get.

AMANPOUR: So you really are in a wait-and-see mode.

Just very, very briefly, Bloomberg has apologized for stop and frisk, but it seems to keep haunting him and following him. Do you see that as a black

— I was going to say a black mark, but you know what I mean — as counting against him?

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I think that the people who suffered through that, the people of color in New York who were harassed by the police, I think we

have got to hear from them and see what that’s all about.

Their experiences really define Mr. Bloomberg’s presidency as far as that issue is concerned. So we will find out and get down to the facts. We have

to find out what the facts are. And that takes discussion.

So I’m eager to hear what everybody has to say on that, Mr. Bloomberg, the other sides, and then we will make our choices.

AMANPOUR: Well, we will hear first in the Wednesday night debate.

But let me just finish by asking you, you lost, the world lost a great, great teammate, Kobe Bryant, of the Lakers last month. It shocked so many

people.

Just your thoughts now, a month or so later, on the void he leaves and the legacy, I suppose.

ABDUL-JABBAR: Well, I don’t think that we have really gotten to the point where we understand what that legacy is going to be, because we’re still

getting over what happened and still don’t really understand it all, such a senseless loss of life.

And that’s really what we’re left with, a big hole in a lot of people’s lives. It’s so unfortunate. But there we go.

And I just send my condolences to Kobe’s family and friends. And, along with all of the other people that helped him and supported him, I’m shocked

and saddened by it.

AMANPOUR: Well, what — again, you’re both Lakers. What was your — and do you have a standout memory? You knew him very well. I mean, just some

personal recollection that is special?

ABDUL-JABBAR: I remember Kobe’s daughters really well. I got to know them away from the game and everything just as a parent and grandparent.

I think that that’s really what the real tragic aspect of the loss has to do, you know, a young life just gone, along with eight other lives, no

reason for it.

AMANPOUR: Exactly. Well, everybody is still grieving.

We thank you very much, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, for those thoughts and for the documentary.

“Black Patriots: Heroes of the Revolution,” premieres tonight on The History Channel.

And now we turn to a controversial new app threatening to weaponize profiling like we have never seen before.

Clearview AI is a ground-breaking facial recognition technology that scrapes billions of images from social media and all across the Internet.

It is currently used by the FBI and hundreds of law enforcement agencies in the United States and Canada to identify suspects.

Hoan Ton-That is the founder and CEO of Clearview.

And our Hari Sreenivasan asked him what the company can do to keep law enforcement and other users from abusing this powerful new tool.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN, CNN INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: So, let’s start with the basics. How does automated facial recognition work?

HOAN TON-THAT, FOUNDER AND CEO, CLEARVIEW AI: This is — what we do at Clearview is actually not automated facial recognition.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: We’re an investigative tool for after-the-fact investigations.

So, after someone has committed a crime, there’s probable cause, for example, a bank robbery, then a detective can use our tool, take a photo of

that face, and then perhaps have a lead into who that person is, and as a beginning of an investigation, not the end.

SREENIVASAN: So let’s say you get a picture of a bank robber. How is the software working? How does it find that face in a sea of faces?

TON-THAT: What happens is, the investigator will find a right screencap of the right frame, and then run the app, take a photo, and it searches only

publicly available information on the Internet, and then provides links.

So, it just looks like and feels like Google, but you put in faces, instead of words.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

So how does it know my face is different than yours, when we actually — in sort of computer-speak, what is it looking for? What are the similarities,

what are the differences that make our faces distinct?

TON-THAT: Yes.

So, the older facial recognition systems, because facial rec has been around for 20 years…

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TON-THAT: … were a lot more hard-coded. They would try and measure the distance between the eyes or eyes or nose.

And what the next generation of artificial intelligence has allowed is a thing called neural networks, where you get 1,000 faces of the same person,

different angles, or with a beard, without a beard, with glasses, without glasses.

And the algorithm will learn what features stay the same and what features are different.

So, with a lot of training data, you can get accuracy that’s better than the human eye.

SREENIVASAN: So, training data means what, more samples?

TON-THAT: Yes, more samples.

SREENIVASAN: So, the larger the sample set, the better the software gets?

TON-THAT: Exactly.

SREENIVASAN: And how big is a sample set that you’re working with now?

TON-THAT: So, we have a database now of over three billion photos.

SREENIVASAN: Three billion photos?

TON-THAT: Yes, correct.

SREENIVASAN: Where did you get three billion photos from?

TON-THAT: They’re actually all over the Internet. So you have news sites, you have mug shot sites, you have social media sites. You have all kinds of

information that’s publicly available on the Internet.

And we’re able to index it and search it and use it for — to help law enforcement solve crimes.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

So let’s see a demo of how this works. I’m going to try to show you some photos. And these are photos that we have permission from a couple of the

people. We’re probably going to shield their faces.

Now let’s try a blurry picture.

TON-THAT: OK.

SREENIVASAN: I don’t know if this will work or not.

But, a lot of times, a police officer is not going to work with a beautiful, perfectly in-focus shot, right?

TON-THAT: True.

And one thing to keep in mind, the way the software is used and the protocols that law enforcement is only — you can only run a search if a

crime has happened.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: And, two, this is not sole-source evidence. You have to back it up with other things. So it’s a beginning of an investigation.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: So, I have never tried this before. And it’s a little blurry, but taking a photo of a photo.

SREENIVASAN: And now it’s searching all three billion photos at the same time?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, it might actually, because it’s blurry, find other blurry photos.

But it looks like we do have one match there on Instagram. You can click on it, and you can see…

SREENIVASAN: If that’s the same person or not?

TON-THAT: Yes. So, it looks like that’s the actual same photo that we found.

SREENIVASAN: And, in fact, that is the same photo that we found.

TON-THAT: Exactly. So that’s how…

SREENIVASAN: So that was posted on Instagram. And your software had that photo in its corpus of three billion photos?

TON-THAT: Correct.

SREENIVASAN: And is that because that that account was public?

TON-THAT: Yes.

So, it’s a — it was a public account, and that photo was posted publicly.

SREENIVASAN: OK.

TON-THAT: So, if the — if law enforcement is investigating an actual crime — now, it’s not a crime to be at a protest, of course.

SREENIVASAN: That’s right.

TON-THAT: And there are concerns about how the technology is used. And that’s why we have controls in place, and that’s why we want to be

responsible facial recognition. This is just an example.

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

And let’s try somebody who says that she keeps herself pretty limited to social media. Let’s try that face.

TON-THAT: So, again, a photo of a photo, just for demonstration purposes.

SREENIVASAN: And that is the same woman.

So, this — these three billion images that you have got in the system here, pretty much every major tech platform has told you to cease and

desist, stop scouring our pages.

TON-THAT: Mm-hmm.

SREENIVASAN: What does that mean to the three billion image set?

TON-THAT: So, first of all, these tech companies are only a small portion of the millions and millions of Web sites available on the Internet.

So we have received cease-and-desists from some of the tech companies, and our lawyers are handling it appropriately. But one thing to note is, all

the information we are getting is publicly available.

It’s in the public domain. So we’re a search engine, just like Google. We’re only looking at publicly available pages, and then indexing them into

our database.

SREENIVASAN: So, how many police departments are using this now?

TON-THAT: We have over 600 police departments in the U.S. and Canada using Clearview.

SREENIVASAN: And when you say using, that means that they are running this, they — their officers have them in hand? How does it work?

TON-THAT: So, typically, it goes to the investigators doing crimes. And they might have a different number of people using it to solve cases.

SREENIVASAN: Do you have the equivalent of like a God View that can see what every department and every investigator is searching for?

TON-THAT: So, what we have done is, we have an audit trail from each department.

So, say you’re the sergeant or you’re the supervisor in charge. You can see the search history of people in your department to make sure they’re using

it for the proper cases, so they’re not using it to look people up at a protest.

You need to check that they have a case number for every search that they have done and things like that, yes.

SREENIVASAN: So, who is policing the police?

TON-THAT: So, they have procedures in place about how you’re meant to use facial recognition.

So, some of these departments have had it for over 10 years, procedures in place on how to properly do a search and all the guidelines and they — and

so on.

So they, I feel, have pretty good procedures in place. And police are some of the most monitored people in all of society. So, you know, they don’t

want to make a mistake, and we don’t want them to have any abuse.

So, we’re building tools for the police department, and we’re adding more things to make it secure for them.

SREENIVASAN: How do I know how many bad guys the cops have gotten using this vs., for example, the number of good people that it might have wrongly

identified?

TON-THAT: Yes, that’s great.

So, I think the history of our tool, we haven’t had anyone wrongfully arrested or wrongfully detained with facial recognition at all. On the flip

side, all the cases that are being solved — we get e-mails daily. I got one two days ago that said that these — highway patrol could run a photo

of someone they couldn’t identify, that he was picking up three kilos of fentanyl.

So, we get e-mails like that every single day from law enforcement. So we really think that the upside is completely outweighing the downside. I

understand that there are a lot of concerns about misuse and all that stuff.

But, so far, they have all been hypothetical and misidentification. So our software is so accurate now, as you can see in the demo — and we made sure

it works on all different races and all different genders — and it’s also not used as evidence in court.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that you said interested me. How do you make sure that the software is able to find distinctions in people of color

or by gender?

TON-THAT: Mm-hmm.

So, one thing our software does is, it does not measure race and it does not measure gender. All it measures is the uniqueness of your face. And

when you have all this training data that we have used to build the algorithm, we made sure that we had enough of each demographic in there.

So, other algorithms might be biased in terms of not having the minorities, enough training data in the database for them. So, that’s something we made

very sure of.

And we have done independent testing to verify that we are not biased and have no false positives across all races.

SREENIVASAN: You’re Vietnamese-Australian, right? But you have been in the United States for a few years.

And I have just got to ask, have you ever been stopped and frisked?

TON-THAT: No, not yet.

SREENIVASAN: Right?

I mean, do you know what that is — why that’s so important in the United States, why people have this feeling that, even if there are 99.9 percent

the police are out to protect us, they’re doing a great job, there have been so many encounters with police, for — certainly for people of color,

where they feel like, I don’t need one more tool where it will be used against me on the streets of New York or some other city, right?

TON-THAT: Absolutely.

So, we’re — again, we’re not real-time surveillance. We’re an investigative tool after the fact. And, yes, stop and frisk was definitely

too aggressive for what the benefits were for — it was for.

And I think, with our kind of tool, we would be able to even decrease that kind of behavior amongst the police.

If you’re just profiling people based on the color of their skin, you know, that’s not a fair thing. And I think that’s why there was such a backlash

against stop and frisk, because people of color were just totally innocent, getting stopped and frisked all the time.

Now, maybe in a different world, with — you could be a lot better with accurate facial recognition.

SREENIVASAN: But here’s the thing.

At this point, I’m a 14-year-old boy of color walking down the street. A police officer now has your app, also puts my face into the system. Over

time, the next time I have a photo of me taken for any reason, now here’s a track record of one more photo that’s been taken by a police officer.

Is there something suspect of this child, right? I mean, that’s one of the ways that people fear that these technologies will be used against us.

TON-THAT: Yes.

So, right now, just to be clear, this is used as an investigative tool. So, people aren’t out there just taking photos in the wild.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: Some crime has happened, there’s probable cause, et cetera. And…

SREENIVASAN: That’s your intent.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: That’s the intent of your company today, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: But the technology is what the technology is.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: If someone else had access to this tool, couldn’t it be used in a different way?

TON-THAT: Yes, that’s why we have a lot of policies in place.

But, also, technology is not done for its own sake. It’s always run by people, right? We have a company. We have very strong beliefs in how it

should be used, and so does society. And we don’t want to have anything that’s too conflicting, or we don’t want to create a world we don’t want to

live in personally.

So, yes, maybe someone else could build something similar and use it — misuse it for other things, but that’s not what we’re going to do.

SREENIVASAN: So how do I have that assurance?

Look, you’re a smart guy. There’s lots of tools that have existed on the planet, like, you could say cars or guns, right? They’re — it depends on

who is driving them and how they’re used. And we have tons of regulations and laws and safety measures in place.

And even with that, we have thousands of people that die in car accidents, and then we have mass shootings. On the — the edge cases are very, very

bad, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And that’s with lots of guardrails in place.

In this arena, there’s no legislation.

TON-THAT: Well, listen, we’re actually for regulation in a lot of ways.

We think it is a powerful tool. I think the right — the public has a right to know how it’s being used currently. That’s why we’re here and talking to

everybody.

But I also think that federal guidelines on how it’s being used would be a — probably a very positive thing. It would put the public at ease and it

would — law enforcement would understand, this is how you use it, this is how you don’t use it.

And I think the choice now is not between, like, no facial recognition and facial recognition. It’s between bad facial recognition and responsible

facial recognition. And we want to be in the responsible category.

SREENIVASAN: You’re also trying to take this business global. It’s not just police departments here, but there have been maps in some of your

literature that says that you’re selling it overseas.

Is that true, right?

TON-THAT: So we’re actually focused on the U.S. and Canada. But we have had a ton of interest from all our around the world.

So, what is interesting is, as the world’s more interconnected, a lot of crime is also global. But we’re very much focused on the U.S. and Canada.

And it’s just the interest from around the world is just a sign that it’s such a human need to be safe.

SREENIVASAN: But, inevitably, as you just said, the rationale for having it overseas is that crime knows no borders, right?

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And that you want to help law enforcement authorities all over catch bad guys.

But those other countries might have different value systems.

TON-THAT: Sure.

I — there’s some countries that we would never sell to are very adverse to the U.S.

SREENIVASAN: For example?

TON-THAT: Like China, and Russia, Iran, North Korea.

So, those are the things that are definitely off the table. And…

SREENIVASAN: What about countries that think that being gay should be illegal, it’s a crime?

TON-THAT: So, like I said, we want to make sure that we do everything correctly, mainly focus on the U.S. and Canada.

And the interest has been overwhelming, to be honest…

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: … just so much interest, that we’re taking it one day at a time.

SREENIVASAN: You also said something like you don’t want to design a world that you don’t want to live in.

TON-THAT: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: What does that world look like, just so I know?

TON-THAT: Great.

So, I think that your private data and your private thoughts, your private e-mails, they should stay private, right? I don’t think that it’s — unless

you have very, very rare cases around national security, which is what the FISA courts are for, surveillance into everyone’s private messages — I

don’t think that’s the right thing.

But I do think that it’s fair game to help law enforcement solve crimes from publicly available data.

SREENIVASAN: You know, we have had — post sort of the Edward Snowden revelations, we have plenty of evidence of our own government overstepping

the bounds.

What if your software facilitates a world you didn’t want to live in?

TON-THAT: Well, we’re not going — we make sure that won’t happen.

But, to be clear, like…

SREENIVASAN: Look, do you think Mark Zuckerberg thought that his software would be manipulated in an election? No.

TON-THAT: Of course he didn’t.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: But I think Facebook provides the world a lot of good. It connects a lot of people…

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: … that otherwise wouldn’t have been connected. Tons of people have gotten married through Facebook. And I think the benefit of it

outweighs the downside.

SREENIVASAN: Again, it’s a platform.

TON-THAT: It’s a platform.

(CROSSTALK)

SREENIVASAN: It’s a — right?

But what I’m saying today is, is that are you planning today, are you figuring out, what are the edge cases, and how do I insulate myself against

the worst thing that could happen?

TON-THAT: Exactly.

SREENIVASAN: Because it seems like, if you can design something, there’s someone out there very smart trying to figure out, how can I abuse his

tool?

TON-THAT: Exactly. We always think of the edge cases. That’s where we want to go with everything, when you think about risk mitigation.

So, like you said, cars, very regulated, but you can take a car and drive it into a building. Very rarely happens. Same with guns. There’s more

controls over guns, and school shootings and shootings are very unfortunate to have in this country.

And we have actually helped with some of these active-shooter cases. That’s pretty interesting.

But with this tool, it’s — you know, what’s the worst that can happen with it? It’s — we always think about that and how to mitigate that and make

sure that only the right people are using it, and that the more sunlight you show on the use of the tool, and the more controls for law enforcement

— so maybe someone doing too many searches of the same person or — there are more things we can add to our system.

And that’s why we’re excited to start the debate or, like, learn more from people in government about what is the right thing to do.

SREENIVASAN: There’s a certain level of obscurity, almost, that feels part of being human, that I interact differently with you than I do with my

family, than I do with my colleagues. Right?

So, I guess it’s kind of a philosophical question, but do I own my face anymore?

TON-THAT: It’s your face. Of course you do.

But, like, what you’re talking about is more like social context in who you’re hanging out with, et cetera.

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: So…

SREENIVASAN: I mean, context starts to dissolve if it’s really up to your search. Right?

Your search, if you did my face right now, which you can do, there’s going to be hundreds and thousands of pictures of me probably doing television

shows and whatever. There might be some with my family. There might be some with whatever. It’s all — there’s no context. It’s just all one set of

images.

TON-THAT: Yes, exactly.

And I agree with you. Like, this tool should be used in the right context. And that’s why we found law enforcement was by far the best and highest

purpose in use of facial recognition technology.

Now, on the flip side, like you said, if I had this app and I saw you on the street and I ran your photo…

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TON-THAT: … and I could ask you questions and know a lot about you, I don’t think that’s a world I want to live in either.

SREENIVASAN: How do you ensure that whoever takes over your company when you move on to the next thing lives by these same values?

TON-THAT: So, for us, it’s about the company culture, what we believe in, but, also, the real value and the thing I get excited about every day is

the physic value from all the great case studies we have and all the crimes we help solve.

So, that’s what we’re really in for it. We’re not really in for it for the money. And other people have said, maybe you should do a consumer — it’s a

bigger market. Many venture capitalists have said, law enforcement is a small market. Why don’t you do something else?

But we really believe in the mission, and we believe the value to society is so much higher if we do it in a responsible way.

SREENIVASAN: Do you control the bulk of your company, similar to what lots of tech company heads have done, meaning you have more voting shares, like

the Google guys or Mark Zuckerberg or anything else?

Let’s say at some point your investors outvote you and say, we really should be looking at the bigger picture here, because we can make more

money, we’ve invested this for a return? They’re not in it for the psychic value. They’re in it for the dollars.

TON-THAT: I think investors have both motivations.

You can’t say they’re always in it for the money. And we try and pick investors that are very much aligned with the mission. That’s why the ones

who wanted us to be consumer, we rejected. And the ones who really believe in law enforcement and law and order, we worked with.

And, for now, we do control the vision and the direction of the company. And you got to understand, businesses are here to make money, and that’s a

good thing. But it’s more important to provide value to society. And I think we’re doing that at a really big level.

SREENIVASAN: Who are the big investors, or how many investors do you have, or what part of that information do you share?

TON-THAT: We have — we have done two rounds so far of investment, a seed round and a Series A. And we don’t really talk about our investors.

SREENIVASAN: So here’s the thing.

It’s like, I want to believe the fact that you want to pick investors that are mission-driven, right? But if you don’t know who those are, that

doesn’t look like a lot of transparency either.

TON-THAT: Yes, they just don’t want to be named at this point.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TON-THAT: And we want to protect their privacy. That’s important to us.

SREENIVASAN: That sounds the most ironic, because…

TON-THAT: OK. Sure. I know.

(LAUGHTER)

SREENIVASAN: Right? It’s like I get that you want to protect their privacy, but everybody is looking at this app, saying, well, what about our

privacy? What about the three billion images that exist out there?

TON-THAT: We have Peter Thiel as one of the investors involved, Naval Ravikant.

SREENIVASAN: Sure.

TON-THAT: We have a whole wide range of investors.

And we’re thrilled to work with them. We love their support. They’re all U.S.-based or U.K.-based. And that is important to us to make sure it’s in

the hands of American investors.

SREENIVASAN: Hoan Ton-That, thanks so much for joining us.

TON-THAT: Thank you very much. Appreciate it.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR:Finally, Wednesday night’s democratic presidential debate in Las Vegas will mark the first time that a climate journalist would be a moderator.

She’s a prominent Latino reporter for Telemundo and she’ll be joining us on the show tomorrow.

And also on the program, a journalist whose groundbreaking investigation for the Atlantic reveals how the trump campaign’s strategy could be a game changer in November.

Be sure to tune in for all of that.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Find out what’s coming up on the show by signing up for our daily preview.

Visit pbs.org/amanpour.

Thanks for watching ‘Amanpour and Company’ and join us again tomorrow night.