Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

What happens when political appointees take over for the experts? From Ukraine to the Veterans Administration, I speak with President Trump’s

former VA Secretary, David Shulkin.

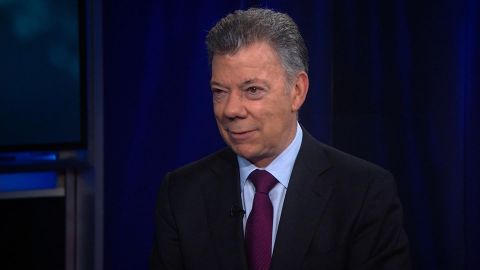

Then, from the Far East and the Middle East, to Latin America, citizens take to the streets to voice discontent. Former Columbian President,

Santos, joins us with solutions.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOHN LITHGOW, ACTOR: Trumpty Dumpty wanted a wall just to rob a rabid political (INAUDIBLE).

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Actor, John Lithgow, goes unapologetically and poetically political. He speaks with our Hari Sreenivasan about his book “Dumpty: The

Age of Trump in Verse.”

Welcome to the program, everyone. I am Christiane Amanpour in London.

What it’s like for a policy expert to serve in the current U.S. administration? That question is front and center today as the National

Security Council’s top Ukraine expert, Army Lieutenant Colonel, Alexander Vindman, testifies behind closed doors to House investigators.

Vindman personally listened in on President Trump’s July phone call with Ukraine’s leader and told him investigators that he was immediately

concerned, “I did not think it was proper to demand that a foreign government investigate a U.S. citizen. Following the call, I again

reported my concerns to NSC’s lead counsel.”

David Shulkin is intimately familiar with happens when policy places second fiddle to politics. The former secretary of Veterans Affairs is the first

former Trump cabinet member to speak completely openly about his experience. His new book is called “It Shouldn’t Be This Hard to Serve

Your Country: Our Broken Government and the Plight of Veterans.” And he is joining me now from Boston.

Secretary Shulkin, welcome to the program.

DAVID SHULKIN, FORMER U.S. SECRETARY OF VETERANS AFFAIRS: It is a pleasure to be here.

AMANPOUR: Let me just first start by asking you the connection, your connection of what we are seeing on Capitol Hill today, and that is yet

another expert who was on the NSC talking about what happens when political appointees and others take over from expertise. When you see what Bindman,

according to his statement anyway he’s saying, how does that resonate with you today?

SHULKIN: Well, the story that I share in my book about what happened to me is extremely similar to what I am saying happened again. It is a repeat

pattern of behavior where dedicated career employees, people really trying to serve their government as public servants are being interfered with and

seeing things that, frankly, should not happen. And I am so glad that there are so many people willing to speak up and talk about what’s right.

AMANPOUR: Well, why do you think that’s happening now? I mean, you’ve obviously had good deal of time to reflect, to write and now, you are

speaking about it. Just before we get into the nitty-gritty of what happened to you, why do you think more and more people are coming out now,

whose jobs are on the line and at stake by coming out, they are currently serving?

SHULKIN: I think people are seeing a real risk to our democracy and seeing their trusts be eroded within government and feeling a real duty. People

who served in government often have other choices. I came from the private sector myself. But our belief is, is that citizens need to do the right

thing to make this government work. And speaking out when they see something wrong, it’s an American value.

AMANPOUR: So, Secretary Shulkin, let me ask you about what happened to you. In your book and in op-eds and the like, you have written about a

toxic and chaotic and subversive situation when it comes to outside appointees or inside appointees doing end runs around policy appointees

such as yourself.

What happened to you who, after all, you were specifically chosen by President Trump even though you started under the VA secretary or in the VA

under President Obama?

SHULKIN: Yes. I was one of the very few, the only one in the cabinet who had worked for President Obama and I was confirmed a hundred to zero. And

I had hoped that we would continue to keep veterans’ issues and doing better for our country’s veterans apolitical and outside of all the games

and then ship it I was watching happening in Washington.

But unfortunately, that just wasn’t the case.

And a few political appointees in the organization, in the Department of Veterans Affairs thought that the Department of Veterans Affairs should be

moving in a different direction, towards privatization and I just wasn’t willing to go along with that. I didn’t think that was the right thing for

veterans or what veterans wanted.

And so, we had a clash. And ultimately, President Trump ended up changing his mind and said he wanted to go with a different direction for a

different secretary.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s just go a little bit from the beginning. We’re going to show now a little bit of tape of President Trump essentially talking

about you. This was back in June 2017 when things were going well.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: I also want to express our appreciation for Secretary Shulkin who is implementing the dramatic reform

throughout the VA. It’s got to be implemented. If it’s not properly implemented, it will never mean the same thing. But I have no doubt that

it will be properly implemented. Right, David? It better be, David. We’ll never have to use those words. We’ll never have to use those words

on our, David.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, I mean, it really could not be more of a hearty endorsement from the president to you. You did have — just describe your

working relationship? I mean, you did go to the White House, you had meetings. You had a pretty good working relationship.

SHULKIN: Well, I — we were getting a lot done. And frankly, we were fixing a lot of the things in the VA that had been broken for decades. And

so, that very first year when I was secretary, we got 11 bills through Congress and in a bipartisan way and the president signed them.

And frankly, I think the president enjoyed seeing all the progress that was happening. But as you are seeing, even as today, there are so many people

now bringing their opinions and their political ideologies into policymaking that, frankly, it gets derailed. And it’s really important

that the work government stay focused on what’s right for the people serving and not get into these political derailments.

AMANPOUR: So, describe for us then what was the political drama that surrounded you? I mean, there were political appointees, there were also

friends of the president, people who were your subordinates inside the VA who, as I said, were doing end runs around. How did that happen? What

started to make your tenure there go off the rails?

SHULKIN: Well, I think that, you know, I was not some of the initial political appointees, original choice for secretary. I think their choice

by the president of selecting me was somewhat of a surprise. And so, I wasn’t easily controlled. I was following a bipartisan path.

I was following what I thought was right for the veterans, and that frustrated them to the point that they ended up doing essentially internal

sabotage, leaking false information to takeaway for my ability to lead the organization, creating enough political turmoil that ultimately did end up

derailing my tenure of secretary. And frankly, stopping some of the progress we were making.

And the real issue that was — the central issue was this issue of do we continue to support a strong VA or do we move much more rapidly towards

privatizing a system that, frankly, I think is part of our commitment that we’ve made when our men and women go off to defend us that we’re going to

be there before them when they come back home.

AMANPOUR: Well, here is the thing. I mean, you have that view and you took that view to the president at a particular time and he tended to side

with you. You know, you were speaking about the importance of what you’ve just told me that it can’t all suddenly be privatized, that, as you say,

veterans deserve a huge amount and it can’t all happen overnight.

And while you were having a meeting with the president, he called a friend and an advisor who happen to be a “Fox News” contributor, he’s name is

Peter Hegseth, supporter of privatization, asked him to weigh in. And incredibly, Hegseth apparently said, is according to what you say, I have

the secretary here with me, he says, we can’t do this all now because it would cost us over $50 billion. So, Pete, we have to take our time.

So, the president basically kind of pushing away those who might be on the privatization now bandwagon. I mean, that was a victory for you. How,

again, did that start getting whittled away? What happened after that?

SHULKIN: Yes. When I had a chance to directly talk with the president and present my views and give him a full picture of why I was making the

decisions that I made, I generally found his support.

What was very hard to control was where he got his other information from.

And I think we see this that the president and many presidents will do this, reach out to people that they know, their advisors and get

information. The information that the president get — was getting from outside people, and the example you just used of the “Fox News” reporter is

an example of that, was often very different than the information that I was giving him as secretary.

And ultimately, the president needs to decide which information he’s going to rely upon and make his decision based upon. And, you know, I think that

I had no control over where he was getting all of this different information and the sources that he would choose to get it from.

AMANPOUR: It should be said that before being secretary of the VA, you were in private practice, right? I mean, you were a physician, you are.

You had turned around many — or several significant failing hospital institutions. And so, you came to this with a huge amount of expertise.

And then, we’ve just described the support you had from the president and how it was being whittled away. Let’s just show just how you learned you

were being cut out of the loop. This is another meeting in the White House about an upcoming meeting.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TRUMP: We are having a meeting tonight at what we call (INAUDIBLE) the Southern White House. It seems to be the most convenient location.

Everybody else wants to go to the Southern White House. So, are you going to be in that meeting? You heard about it, right? It’s going to be great.

All about the VA.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Yowzer. What was going in your head there? I mean, you said — you shook your head no and then you nodded your head yes. What were you —

what was happening as he said that to you?

SHULKIN: Well, I was confused as probably everybody. That happened to be a nationally televised meeting where that happened. How could you have a

meeting about veterans’ policy and the futures of veterans’ care in this country and not have the secretary of VA there? That began to allow me to

see some insights into how the decisions making was going on.

And it was always somewhat of a surprise when you work in the administration not knowing exactly where the president was getting his

information from. And, you know, it was a certainly a source of concern for me because I wanted the president to have the right information and the

information that was coming from the secretary who was Senate-confirmed appointee in the cabinet to make sure that the president was getting the

right information.

AMANPOUR: Secretary Shulkin, I just want to refer back. The president has basically poured cold water over Colonel Vindman who is testifying today,

saying, he wasn’t on the call, I don’t even know who he is.

And as you know, your critics will be coming at you because of the ethic lapse you were, you know, confronted with. And we have basically “The

Washington Post” headline, “VA chief took Wimbledon, river cruise on the European work trip; wife’s expenses covered by taxpayers.”

Now, there was an investigation. You say a lot of this was distorted or false, but the internal report said that you did mislead agency ethics

officials. Tell us about that and how you think that is going to be, you know, used to damage your credibility now on this issue.

SHULKIN: Well, first of all, you know, I wrote the book to give the details of that. So, I am going to let the readers make up their mind. I

was completely transparent into everything that happened and I maintained that absolutely everything was done the way that it should be done. But,

you know, that’s something about two years ago.

I think what we are really seeing is that there is an effort underway to discredit people who speak out and are doing it as a sense of duty. And I

knew when I wrote this book and I knew when I would speak out that there will be people coming after me attacking my integrity and my ethics.

But I feel that it’s my duty as an American citizen having had the chance to have had this view from the seat that I had to speak out, because I

believe public service is in real danger if we don’t support the people that are trying to do the right thing. And that we need to reset in

Washington to create an environment where we can all perform better and make this government work better for its citizens.

AMANPOUR: Secretary Shulkin, you — can you talk about, you know, sabotage? And it’s almost like Keystone Cops. I mean, it’s almost like

comedic if it wasn’t so utterly serious. There’s this famous copy machine incident where you actually found out that you were being actively

sabotaged, undermined, plotted against by these, appointees, political appointees who, again, were your subordinates. You — they were working

for you, not vice versa.

SHULKIN: Right. You know, I am a physician. I’m trained in science. And so, while many people in my agency were telling me, watch your back.

There are people in your agency working against you, I, frankly, didn’t spend much time paying attention that. I had too many important things

working on behalf of veterans to worry about what I thought were games.

Until one day, they happen to leave a memo detailing their exact plan to have me removed. They left it on my copy machine and a staff member

brought to my deputy secretary who brought it to me, were clearly outlined in writing, these political appointees were planning to have me removed, my

deputy secretary removed, my chief of staff, my acting under secretary removed and replace them with people that they thought were more

ideologically aligned with their views of where the VA should go.

And so, at the point then, I just couldn’t ignore it. And it was really that type of hard evidence.

AMANPOUR: And then, you learned that you actually fired by tweet and that has happened quite a few times.

Secretary David Shulkin, thank you very much indeed for joining us. As you say, it shouldn’t be this hard to serve your country. Thank you indeed.

Now, a discontent isn’t just for government insiders, it is rising from the street all around the world. Political protests in Hong Kong, pocketbook

demonstrations from Lebanon to Chile, citizens in rich and poor nations are voicing their dissatisfaction.

And in Beirut this afternoon, Prime Minister Saad Hariri has become the first to fall on his sword, announcing his resignation after nearly two

weeks of grassroots anger.

The protests were treated by a proposed tax WhatsApp calls. Today, there were some violent confrontations with Lebanese security forces such as the

one you’re seeing here. An incredible 37 percent of Lebanese under the age of 35 are unemployed. And the U.N. says, the poverty rate has risen by

two-thirds since 2011.

Now, Mona Fawaz is a professor at the American University of Beirut, and she’s been heavily involved in organizing the protest and working on a set

of goals. She joins me from Beirut where demonstrations are still going on, and it’s pretty loud there at this hour.

Mona Fawaz, thank you very much for being with us.

MONA FAWAZ, PROFESSOR, AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you from the beginning. We’ve seen prime minister listen to what the street had said and he has offered his

resignation. But what does it mean? What happens next? There will be a caretaker government. The president is still in place. What happens next?

FAWAZ: Well, I think, in order to understand the significance of today’s resignation, and as you noticed, I’m having a hard time hearing you, you

have to hear the celebrations that are happening on the street and to really locate them in their context.

What people are celebrating today is not necessarily the resignation as much such as this the opportunity that the country has to set itself on a

new course. Of course, that’s different from the financial crisis, from the poverty, the environmental deterioration and the cost that we have been

living in the last 30 years.

So, there was a moment in which the protest that started, that were sparked really by an unjust attack turned into a massive protest that went beyond

the usual size but also, way beyond the usual locations in which the protests were happening.

And by (INAUDIBLE) account, there were some 2 million people who were on the streets across all the nation and they were first really demanding more

justice and the life and dignity. But then when they saw themselves altogether, they’ve — and conversations began to happen and people noticed

that what was keeping them so divided was this kind of government through which they were, with sectarianism, with mode of government that has been

in place since the 1990s. They began to demand something more.

They demanded resignations. But they essentially demanded to certain place a different of government, a different mode of governance, a way in which

we can really begin to build true form of citizenship that can take the country, drive the country out of the financial crisis, the poverty and

give us an opportunity to live with dignity. This is really what it is about.

AMANPOUR: So, Mona Fawaz, dignity is very important, fairness is very important, the desire for a non-corrupt state is very important. But one

of the standout issues for your country is the sectarianism, and that has been the sort of de facto reality in post-civil world. How does the future

look if these very key offices have to be shared out amongst, you know, different fates, the Sunni Muslims, the Shia Muslims, the Druze?

FAWAZ: Look, I mean, if you hear the songs down there, what they are actually saying is that finally we are liberated from these divisions.

I am not being delusional and imagining that sectarianism will disappear overnight. But what I’m noticing is that over the last few years, we’re

seeing one movement after the other, people increasingly taking stands against sectarianism, people increasingly feeling that the way in which

they’re categorized into sects and religious groups is basically undermining the possibility of building a nation.

And this is what we’ve been hearing in the streets for the last three — two weeks, excuse me. So, I mean, and if you look at the teachings that

we’ve been organizing, if you look at the debates that are happening on the streets, you hear a lot of people from all works of life coming and then

converging on this idea that yes, we’ve been engrained in so much corruption and this corruption is really protected by a sectarian regime

and we want to imagine a different possibility.

And it is becoming more and more the song of the streets. So, really, the hope is to see the response coming from the current leadership in the

appointment of an independent government that’s far from the secretariat divides and then can truly drive the country through the moment of

financial crisis that we are living.

AMANPOUR: Mona, as you know, the group Hezbollah, which the whole world knows about because of its reactions with Israel because of what it’s been

doing on behalf of Iran and Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad in Syria. Hezbollah has been also talking about this.

And actually, the leader, Hassan Nasrallah, has made some, you know, fairly unsubtle threats. Can we just play what he said recently about these

demonstrations and then I will ask you about it?

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HASSAN NASRALLAH, SECRETAR-GENERAL OF HEZBOLLAH (through translator): In view of the difficult monetary, economic and the living situation, in view

of the political tensions locally and in the region, in shadow of what could be a target internationally an regionally, vacuum will lead to chaos,

vacuum will lead to collapse.

I am scared for the country. We are scared for the country. We are scared that there may be someone who wants the take Lebanon and create social,

security and political tensions that would lead to civil war.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Mona, he is raising the possibility of civil war again and lamenting a vacuum. What do you say to that?

FAWAZ: Look, I mean, I think that what we heard from the speeches of everyone who has some kind of leadership in the last week has been one of

threatening with vacuum. But out constitutional mechanisms actually protect us from vacuum. They are the caretaker government.

And if there is a true political will to set in place an independent government, the constitution completely allows for it. So, there is no

need for a vacuum.

I really want to go back and focus on how organic, decentralize, real the movement has been. It has been in all cities, it’s been in every little

town, spontaneous debate sessions coming up in public spaces, people rediscovering the possibility of collectives. And I think this is what

scares actually everyone who has built its leadership over the country, over the idea that we’re divided groups.

I think it is a unique moment in our nation’s history. And I really hope – – I mean, it’s not going to happen tomorrow but I really hope that this opportunity to set the country on the right place can happen and there is

the possibility to actually capitalize on it right now.

AMANPOUR: OK. Mona Fawaz, thank you so much for joining us today.

And, Lebanon isn’t not the only country where protests will change the face of government. In Hong Kong today, the (INAUDIBLE) chief executive, Carrie

Lam, was forced to deny media reports that Beijing is preparing to replace her after five months of protest.

And in Chile, President Sebastian Pinera replaced his cabinet on Monday after days of violent protests and misguided military crackdown, where at

least 20 people have been killed.

It is as if much of Latin America is on the march. Peru, Bolivia, Argentina and Columbia have also seen huge crowds on the streets.

Juan Manuel Santos is the former president of a Columbia and Nobel Peace laureate. I ask him whether democracy is failing when it comes to the

fairness that people are demanding.

President Santos, welcome to the program.

JUAN MANUEL SANTOS, FORMER COLOMBIAN PRESIDENT: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So, you see what’s happening in Lebanon and what’s happening around the world. But what’s happening on your continent? Latin America

seems to be, you know, erupting in protests all over. The most severe are in Chile. There are even some in Columbia. But in Chile, we’ve seen quite

violent ones with up to 20 people who have been killed.

First and foremost, what do you make of this? Why on your continent is this happening now?

SANTOS: And Ecuador and Haiti and other else.

AMANPOUR: Bolivia. And look, we’ve got a map which shows all of these various different locations.

SANTOS: I think this is a combination of different factors.

First of all, democracy, freedom is one factor, you know. People feel more empowered to protest. Second, inequality. That is — that America is the

most unequal of all continents and people are really feeling that. Third factor is progress. For example, in Chile, this is not a protest of the

lower classes, it’s the middle class that is going out.

And what is happening all around Latin American is that we have been very successful in bringing a lot of people out of poverty, out of the — where

the economy is called the poverty trap. When you get somebody out of the poverty trap, they — their expectations increase geometrically.

AMANPOUR: But let’s just dig down into that because —

SANTOS: But there’s two other factors, inequality and corruption.

AMANPOUR: OK.

SANTOS: Corruption is one of those worst today that everybody is mad about and people are also protesting it.

AMANPOUR: So, would you say that’s the heart of it? Because analysts are trying to figure out whether there is a common thread to all of these

people power movements or people protest movements in the streets, from Latin America all the way to Hong Kong, in Asia, obviously.

Do you think corruption is it?

SANTOS: I would say in certain areas, yes. But there is something that the economy has called the demonstration effect. When people see that in

Hong Kong, people can go out the streets and be even violent, and a regime that is quite drastic like the Chinese allows that, then people feel, if

you can do it in Hong Kong, we can do it here. So, there is a combination of different factors.

AMANPOUR: So, how do you feel then when it wasn’t the Chinese tanks who came into Hong Kong but it was President Pinera’s tanks in Chile that came

into Chile and there are at least a couple of dozen people dead? Is that an overreaction?

SANTOS: I think there were some overreaction. Chile needs and many Latin American countries needs a more ample dialogue. People feel that they are

not participating in the wealth that had been created and not participating in the basic and fundamental decisions. And we need to open up our

democracies and — because elections are sufficient anymore. You need to make people feel that they are empowered in other as aspects.

AMANPOUR: Chile, it’s been out of military dictatorship for three decades. It is one of the richest countries in Latin America. Although, as you say,

it has also the biggest inequality division there. And this was a hike which amounted to 30 pesos of a subway fair ticket. And the government

quickly stepped back and rescinded that but they’re still on the streets.

It is report that the president himself who’s been in office for many years is a billionaire. I don’t know whether it is true but that’s what — is

that true?

SANTOS: It is. That is true.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

SANTOS: He is one of the richest persons in Chile.

AMANPOUR: So, is that appropriate?

SANTOS: Well —

AMANPOUR: I mean, doesn’t that actually from the very top spell the problem or is that just inevitable, that anybody can run and if it is the

richest man in Chile, well, why not?

SANTOS: Well, I think that if he’s very rich, why not? And if he’s willing to make a service to his country, why not? But of course, this

also, in a way, adds to the frustration and the anger of the people.

AMANPOUR: Are you a very rich man? Were you very rich when you were president?

SANTOS: No. But I was rich. I am part of the upper 2 or 3 percent of the population with no doubt whatsoever.

AMANPOUR: Do you think President Pinera should resign? He’s already reshuffled his cabinet. As I’ve said, he stepped back from the subway fare

hike and yet, the protests are still going on.

SANTOS: No, I don’t —

AMANPOUR: We’ve seen what just happened in Lebanon —

SANTOS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — the prime minister resigned.

SANTOS: But I don’t think he should resign.

AMANPOUR: Why?

SANTOS: I think he should hear that — what people are saying and he should sort of make a more profound change, the — what he has done so far

is not enough. I think people are saying, we need more. President Lagos was talking about a constitutional assembly to change the constitution.

There is a frustration in Chile since the transition to democracy because it was controlled by Pinochet. And so —

AMANPOUR: That’s the military dictator.

SANTOS: The military dictator that Chile had for so long.

AMANPOUR: Decades, yes.

Let me just read you a few stats. As I said and as you said, massive inequality. Despite it reduced the number of people living in poverty, you

know, it dropped to 6.4 percent in 2017 from 30 percent in 2000, according to the World Bank.

But half of Chilean workers earned $550 a month or less. It is one of the most unequal of the world’s richest nations, according to the OECD. And

this is one of the protesters have said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: This is the discontent of the people in reality. They are years of oppression, they are years of living in misery. They are

years of government imposed measures at the expense of the people.

And when one goes out to the streets to demand their rights, to demand dignified life, they put us in repressive forces.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SANTOS: She is reflecting this frustration, this inequality that she sees in her country and we see in all of Latin America. But she is neglecting

the fact that millions of people have gone out of public which is normal in the political life. You don’t see the history, you see the future.

AMANPOUR: So what happens when people start to feel that democracy, and in this case, absolute free market. I mean, Chile is one of the most devoted

countries in Latin America to the free market and that’s what made people very upset as well. That, you know, their education and their health and

all of that is very, very expensive for a lot of people who are used to it being much more accessible.

You’ve seen what’s happened just recently in Argentina, the elections brought back the populist, the Pyrenees. You’ve seen, as you mentioned in

Ecuador, and Bolivia, and Venezuela, different, but also in Brazil where populists are coming to power.

What does that say about democracy in your continent, especially which was so heavy in the military junta and the military dictatorships?

SANTOS: Well, it’s happened all around the world. The combination of democracy and a very unjust capitalism. People are seeing that the market

is not functioning for them.

And so what we also need to rethink is our economic model. How can we make our democracy and our economic development more inclusive? And people feel

they are part of the progress. What is happening to the middleclass are not feeling that they are being benefited by the promise of the country.

And also something that has, in a way, exacerbated the frustration, is that the economy, the cycle of the economy has gone down in Chile and every

country in Latin America.

Colombia today is a country that is — a country grows highest this year and we’re not going to grow more than three percent. So there is also an

economic effect on what is happening.

AMANPOUR: Do you think you got the economic effect right when you were president?

SANTOS: I think I did. The figures are there. We were one of the country’s that grew the most. But we grew —

AMANPOUR: But was it just — was it just capitalism?

SANTOS: — by bringing in the people from power into the middleclass and by reducing inequality. We were the country that reduced inequality more

in the last eight years than any other country in Latin America. And that is very, very unfortunate.

AMANPOUR: Now, one of the issues that you had to deal with and you dealt with it for many years was a very long and detailed process of trying to

end the continent’s longest war, which was between your government and FARC, the Marxist rebels.

It’s sort of — I don’t know. Is it hanging in the balance, the peace process right now? The elections this weekend for local government, the

first since the peace deal, how do you assess what happened?

SANTOS: What I think the results of the elections last Sunday are a very clear signal that the country wants the peace deal to continue, wants the

government to be more aggressive in implementing what would have been agreed. And the peace process is going in the correct way even though it

has problems like any peace process. Making peace is much more difficult than making war.

And the peace process, after 50 years of war, was a very difficult peace process. And we’re in that phase of reconciliation of constructing the

peace. And you don’t construct peace after 50 years of war from one day to another. You have to do it in long-term and perseverance.

AMANPOUR: So if you had a prescription for the president of Chile or of the other countries that we’ve spoken about, the ones where protests are

happening. How would you advise them to do what you did which was reduced inequality in Colombia?

SANTOS: Well, what we did was very sort of focused in policies to the people we wanted to help. I even imported a formula from a professor in

Oxford, Professor Amartya Sen.

AMANPOUR: Oh, yes, Nobel Prize winner.

SANTOS: Some that call that multidimensional index to fight poverty and to have a more just economic model, and it worked. It worked very well. You

can do it.

AMANPOUR: Is it still being implemented in Columbia.

SANTOS: It’s been — still being implemented, and with good success.

AMANPOUR: And you said you can do it. So why aren’t the others doing it?

SANTOS: Well, sometimes they don’t have the backing from the Congress, they cannot approve the laws in Congress, for example, Pinera has a problem

with his Congress —

AMANPOUR: In Chile.

SANTOS: — and overall majority. Many countries have that type of problems. I didn’t have it because I’ve created a coalition which allowed

me to implement very drastic and audition reform.

AMANPOUR: So can I ask you? Because this is also a feature of what’s happening, it’s very polarized society, it’s very sectarian societies. Are

you kind of saying that in order to create an economy or a just capitalism, you actually can’t do it just from one end of the spectrum? You actually

need to have coalitions and the whole group on board?

SANTOS: Yes. Polarization is the worst enemy of the government, because what it does is it sort of — it stops a government from being audacious

and taking even unpopular decisions. I had to deal with very unpopular decisions that are unpopular in the short run but necessary in the long

run. If you don’t have a big majority, you cannot do that.

AMANPOUR: So the only way to do it is to get everybody else on board.

SANTOS: Well, or a big majority, yes, and create a consensus that everybody, in a way, feels that they’re part of the deal.

AMANPOUR: Fascinating.

President Santos, thank you very much for being here.

SANTOS: Thank you, Christiane.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Remember that word, consensus?

Now, from a Nobel winner to an Emmy winner, the actor John Lithgow has racked up all kinds of awards, Emmy’s, Tony’s, you may know him from 3rd

Rock from the Sun or Dexter. And soon, you’ll see him portraying the man who reshaped American media and politics before his long history of alleged

sexual harassment caught up with him, Fox News chairman, Roger Ailes.

Lithgow plays him in the new film “Bombshell” which has raised some early Oscar buzz. He’s also turned his talents to writing and he’s out with a

satirical poetry collection, “Dumpty: The Age of Trump in Verse,” which chronicles the last few ruckus years in American politics.

Why this departure? He tells our Hari Sreenivasan.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN, AMERICAN BROADCAST JOURNALIST: Let’s start with the book, it’s called “Dumpty.” Why write it?

JOHN LITHGOW, AMERICAN ACTOR: Well, it was quite a surprise to me. It was a bright idea that it actually grew out of a performance I gave at a New

York public theater gala in Central Park a few years ago. They asked me to sing the major general song from Pirates of Penzance as an entertainment,

and I said, sure, but I’ll perform it in the character of Michael T. Flynn. And I’ll rewrite the final verse.

I’ve dressed up, make-up and hair and wig of Michael T. Flynn and launched into the third verse, took the audience completely by surprised.

When President Obama made me head of all things clandestine, he realized he’d brought to life a governmental Frankenstein, etc. And it killed —

the audience was so surprised and they found it so hilarious and I shared that with my literary agent, not with a view to a book idea. He is the one

who said, there’s your book. And he said, I could sell this tomorrow. So I said — he said —

SREENIVASAN: To half the country. What about the other half?

LITHGOW: Well, good lord, that’s a lot more than what — that’s a bigger percentage than most books of any kind.

SREENIVASAN: Let me start by having you read just the first one that kind of sets the tone for the whole book.

LITHGOW: All right. This sort of explains the title as if it needed explaining. It’s called “Trumpy Dumty.”

Trumpty Dumpty wanted a wall just a rabid political brawl, his Republican rivals both feckless and stodgy succumb in the end to his rank demagogy.

Dumpty’s wall made no earthly sense a boondoggle built an enormous expense, but he promised in speeches despotic and shrill, he’d make certain that

Mexico foot at the bill. Trumpty Dumpty kept insisting more and more citizens started resisting. Sadly, there won’t be an end to this tale, at

least until reasonable people prevail.

That’s a poem that, more or less, declares my bias. I’ve seen it as an introductory.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. How did you — how did you write these? Because some of these — or actually most of these are responding to events as really

they unfold.

Lithgow: Yes. Well, that’s kind of — it’s roughly chronological between June of 2018 and April 1st, 2019 when my deadline hit. And I had to have

all of them completed. That means that an awful a lot has happened since then. Things move so quickly in this day and age. It feels like a century

ago.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LITHGOW: It immediately turned it into a piece of history and piece of political contemporary political commentary.

SREENIVASAN: You know, people are going to watch this and say, oh, Hollywood liberals. What can you expect? Of course, this is what the guy

from Footloose has turned.

LITHGOW: Well, I’ve never — I haven’t turned. I’m an old — my parents were old FDR lefties and I grew up, as many of us, most of us do with my

politics as a kind of birthright, but I just kept them to myself. I don’t think I’m surprising that many people. They probably know I’m a liberal.

SREENIVASAN: You can understand or can you understand how the president has appealed to half the country.

LITHGOW: Yes, it’s true. I mean — there is just different kinds of entertainment. I mean, I’ve been in a lot of things when I was on 3rd Rock

from the Sun, it was certainly at that moment I’ve been doing sitcom on NBC, along came “Survivor.” The beginning of reality T.V. era.

In no time, at all, more people were watching reality television and scripted television. And to me, it was like people were watching lousy

television instead of expert television. The expert entertainers are losing their audience to just the chaos of reality T.V.

It’s just a reality you live with as an entertainer. I just have my standards and my taste are completely different from the standards and

tastes of a lot of people. And that goes for politics, too, obviously.

SREENIVASAN: There’s a reason stage performance where you got to read the words of President Trump in the Mueller report.

LITHGOW: I greatly appreciate you informing me that I am not under investigation —

It was a bridge. It was beautifully edited into an hour 10 minutes piece of theater, really by every at Pulitzer and Tony playwright.

It was simply run it through once and then performed it live streaming online about 15 actors, really good actors whoever was available here in

New York. So there was Kevin Kline, and Annette Bening, Michael Shannon, and Jason Alexander.

It was astonishing how much of the report was written in dialogue. So we were actually speaking the words of these people.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LITHGOW: And there was no tweaking reality. We were simply performing it.

SREENIVASAN: As you were performing, you just recently did Mayor Giuliani.

LITHGOW: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: So you’ve spoken the words of the president and also parodied —

LITHGOW: Yes. Spoken the words of fantastic comedy writers on the staff of the late show.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Mr. Mayor. Mr. Mayor, thank you for joining us.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Beat it.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I haven’t asked you anything yet.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I know, and your facts are all wrong, so.

LITHGOW: And it was — it was hilarious. We rehearsed for all of three minutes and just let it rip.

SREENIVASAN: What would ruddy say right now in this interview? How do you change your face or change your mannerisms or your voice? How do you do

that?

LITHGOW: Well, as always, you have wonderful coconspirators. Your confederates. They did a great half hour of makeup. I brought my own

teeth. They were actually my own teeth from Buckaroo Banzai from 38 years ago.

SREENIVASAN: Still fit.

LITHGOW: I looked everywhere for them and I found them, they still fit and they just simply painted them bright white with water based, some kind of

water based shellac then wash right off.

SREENIVASAN: So once you get into costume, do you feel like you are whatever character?

LITHGOW: Yes. I was more like him than ever. And I was able to look right into the camera, because that’s where the teleprompter was. SO it

looked like I was concentrating deeply. I was only reading the words that roll by. Steven was over here asking me questions. And I just let it

ripped, just this mad parody of him.

You’ve got a movie coming out where you’re playing Roger Ailes. First, let’s take a look at the clip from that movie, a little part of the

trailer.

LITHGOW: Mm-hmm.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: I want to convince you that I belong on air, Mr. Ailes. I think I’d be freaking phenomenal on your network.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I could pluck you out and move you to the front of the line, but I need to know that you are loyal. I need you to find a way to

prove it.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Do you know just got that door blocking his office.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Someone has to speak up, someone has to get mad.

SREENIVASAN: All fantastic actors, Charlize Theron, Nicole Kidman, Margot Robbie.

What’s the key there? I mean, you’re under obviously makeup and so forth? But what’s the key to mimicking someone? How do you get their mannerisms?

How do you study for it?

LITHGOW: Well, I found all that I could video of Roger which was not easy to see himself and might be seen that much. He liked his people to be

seen. I was enormously helped by just all the physical things, the fat suit and the makeup. And this marvelous script by Charles Randolph.

But you just — it’s an imagines of leap, just use my body and my voice. It’s all I have to work for with and just did my best to inhabit this man

and make people briefly forget about what he was really like and just accept my version of it. If there is a trick, that’s as closest as I can

come to describing him.

SREENIVASAN: You know, you’ve had this ability to hit people in different generations. There’s going to be a group of people who listen to this or

watch this, and say, is that the guy whose voice is in “Shrek.”

There is going to be people who grew up watching “3rd Rock from the Sun” and then there’s going to be someone that has sort of “Footloose” reference

or the “Twilight Zone” movie. And these are all different — and then, of course, there’s people who might remember you from the stage in Broadway

when you were coming up.

It’s kind of rare to find people actually able to stay relevant in these different forms for a good chunk of their career. I mean, it is a hard

business to stay on top of.

LITHGOW: It is. I mean, it’s the source of a lot of pride, the fact that I’m still around and still viable, more hirable than ever, turns out I have

— I’ve finally grown into my role of that old man.

SREENIVASAN: So you’ve been training your whole life for this really.

LITHGOW: You know, I grew up in a theater family, and a unique theater family. My father created and produced Shakespeare festivals in the

Midwest.

I mean, talk about appealing to different camps through entertainment. We lived in about eight different places, we traveled around like gypsy wagon.

I worked for my dad. I acted in 20 Shakespeare plays by the time I was 20 years old, mostly in small roles.

SREENIVASAN: Did you want to do that?

LITHGOW: Oh, I’ve loved it. I didn’t intend to be an actor. I was much more interested in being an artist, actually. But I went away to college

and fell into the theater gang. And I was a seasoned actor already.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

LITHGOW: And it was when I was destined to do, no matter in spite of myself. But it was Shakespeare. Shakespeare was at the heart of what my

father did. I knew Shakespeare much better than I knew Arthur Miller, or Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams. They were a mystery to me.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LITHGOW: Even naturalistic acting or something. You know, I was used to yelling in the back row. We have an outdoor theater with no amplification.

Shakespeare wrote for all different occasions and for many different audiences. The man who wrote Hamlet wrote Comedy of Errors. The man who

wrote Macbeth wrote the Merry wives of Windsor. And then he mixed history plays with romantic comedies as you like it. That’s how I sort of back

into this curious career, I think, is acting in many different forms.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LITHGOW: And I like making people laugh every bit as much as I make — I like making them cry or scream out in terror.

It’s just — Shakespeare wrote gothic horror too. I did Pet Sematary last year, he wrote Titus Andronicus.

SREENIVASAN: So you’re really drawing back on the stuff that you learned really as a teenager.

LITHGOW: By osmosis. I never gave that much thought.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

LITHGOW: But I played — you know, they were repertory. The plays that played in repertory. Five, six, seven plays in a summer season. So you’re

playing in very different kind of play every night of the week. And in a sense that’s without ever calculating it. That’s what I’ve done, jumping

from movies and T.V. and stage for one thing.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. So which are you doing to feed what? Do you do films between Broadway?

LITHGOW: Well, the top root for me is the theater. And I return to theater fairly regularly and often. There was a 14-year period when I was

in L.A., when I did “3rd Rock from the Sun,” a lot of movie were — when I was not in New York theater at all. But then I came back and did M.

Butterfly which is one of the great stage experience.

SREENIVASAN: BD Wong. Both of you were — had an amazing performances for that.

What’s it like to take on a role like — I mean, Winston Churchill. I mean, you — everybody’s read about him, there’s plenty of people who

played him in the past, and here you are. How do you redefine it? How do you do this justice?

LITHGOW: Yes. Well, you know, it’s a curious thing. It’s a big English production. And there’s one thing that’s very distinctive about the

English theater tradition. No one is selfish about a role.

When I went over to play Malvolio and it was Shakespeare company, there were three other Malvolios going on. Patrick Stewart, Stephen Fry, and

Derek Jacob, it makes four in all in one season.

Now, In America, you would sulk about that. But not in England. They all run to see each other’s performance, to see what they can use in there.

When I did King Lear, there were like four King Lears in town.

And when I did Churchill, there were Brian Cox was playing Churchill. Gary Oldman won the Oscar for Churchill. And there was — the great Michael

Gambon.

You know, you’re just philosophical. And think, well, I hope that mine is different. I had the advantage of being an extraordinary piece of

material.

Peter Morgan’s marvelous writing, acting with Claire Foy and Atkinson, Harriet Walter, and Stephen Dillane. All these great, great actors.

There was also a wonderful point of view to the crown. It was about the crown and mainly it was about the queen. And it was about monarchy and the

whole role of monarchy and government which is a large and unfathomable subject.

Winston Churchill was a supporting player. I think that’s a great advantage particularly when you’re playing a famous person. I think the

other actors sort of who played Churchill, they carried the burden of being the story.

The same with Roger Ailes. Roger Ailes fits in just right into “Bombshell.” That is a movie about the women of Fox. And it’s about not

just the three big stars, but about a dozen women and how all of them reacted and responded differently to a crisis at Fox. And I was the

crisis.

SREENIVASAN: So do you ever get intimidated now? I mean, now that’s you’ve played such a wide range of roles and kinds of medium? I mean, when

you read a script or when you read a project, what is it that you look for? Or what is it that you —

LITHGOW: You look for good writing. So much springs from good writing. And I’ve done some pieces that were just mediocre writing, if not bad. You

do them for other reasons. Because there are people you want to work with or because you’re going to be paid a lot more money or because it’s time to

do a big studio movie.

I’ve always said, the only difficult acting is bad writing. You just somehow make it work for yourself.

SREENIVASAN: What did you call yourself at the end of — as the movie reel of your life kind of flashes before your eyes, what do you — what do you

think? Is it, OK, I’m an artist, I’m an entertainer, I’m a painter, I’m a drawer?

LITHGOW: Well, at all those things, I’m a very good actor.

SREENIVASAN: There’s that.

LITHGOW: Yes. I am a dabbler for sure. I’m a dabbler as a poet. I don’t call myself a poet. I have too much respect for genuine poets who have —

who write with their own blood, you know, who’s —

SREENIVASAN: You’re a rhymer —

LITHGOW: I’m a clown, really. I’m a smartass clown.

SREENIVASAN: John Lithgow, thanks so much.

LITHGOW: Really, such a pleasure, Hari.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: A jack of all theatrical trades then, John Lithgow. And join us tomorrow for my conversation with movie star, Antonio Banderas. I will ask

him about his recent health scare, a heart attack, and how that helped him get in touch with his own vulnerabilities for this latest film, “Pain and

Glory.” Directed by the greats Spanish director, Pedro Almodovar.

Visit pbs.org/amanpour for our daily preview. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” and join us again tomorrow night.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END