Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to Amanpour and Company. Here’s what’s coming up.

At 83, legendary biographer, Robert Caro, has written a new book and it’s not his long-awaited final volume on Lyndon Johnson. I’ll ask him why this

book now.

And another writer who probes the consequences of power on the psyche. I speak with the Israeli author and psychologist, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen.

Then, America’s forgotten poor rise up in the public. A new movie by actor, director, and writer, Emilio Estevez.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York.

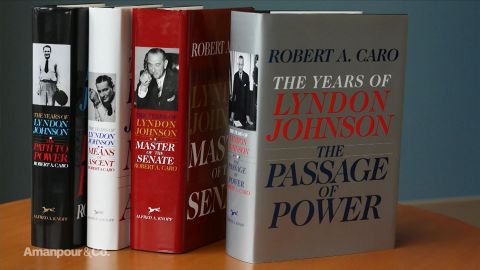

Robert Caro is perhaps America’s greatest living biographer. His iconic books on the life of President Lyndon Baines Johnson and Robert Moses, the

man who built New York in the last century, have won every major award while setting a new standard for insightful, dynamic nonfiction writing.

Now, at 83, Caro gives us a glimpse inside his own prodigious writing process. In his new book, “Working,” he shares his enormous drive to turn

every page, talk to every witness, uncover every fact in pursuit of historical truth.

But while “Working” is a valuable look back at Caro’s life work, it is frankly not the book his fans were hoping for. And that, would be the

long-awaited fifth and final volume of his series, “The Years of Lyndon Johnson.”

Back in 2012, Caro’s last book left us dangling off a cliff just as Johnson become stuck in the quagmire of the Vietnam war. But Bob Caro has never

rushed to finish a book and he’s certainly not about to start now. I’ve been talking to him here in New York, trying to discover his quite unique

working life.

Robert Caro, welcome back to the program.

ROBERT CARO, AUTHOR, “WORKING: RESEARCHING, INTERVIEWING, WRITING”: Pleasure to be here.

AMANPOUR: It is always good to check in with you. I want to talk, though, about your life’s work, your mission, and not necessarily just your

incredibly eminent subjects.

You have quite a slow writing pace, right? I mean, let’s say, if you calculated about a book every decade.

CARO: The writing is fast. The research takes the time.

AMANPOUR: Is that what it is?

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: So, once you’ve done all the research, you’ve pretty much are like an engine?

CARO: Well, I write my first drafts in longhand because that’s really the slowest way of committing your thoughts to paper. And then I go — let’s

say, I do a lot of drafts.

AMANPOUR: But what is it about the research? I mean, clearly, as you said, you spend a huge — the big proportion of your time on a book on the

research.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Give me an idea of why it takes, I don’t know, eight, 10 years just to do the research.

CARO: Well, one thing is that there’s such a mass of papers in the Johnson library. You know, when you go in there, you’re faced with four floors of

boxes. They have 40,000 boxes of papers. They don’t — they’ve never counted the pages but it’s about 45 million pages.

AMANPOUR: Can I stop you right there?

CARO: Sure.

AMANPOUR: Because you are telling me an anecdote which seamlessly leads me into an element of something you did for C-SPAN many years ago, talking

about this part of your research. Let’s just take a listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CARO: You’re looking at four floors. I don’t know how many feet these boxes go back, but it’s a lot. Each of those boxes can hold, and a lot of

them, unfortunately do, 800 pages. So, the Johnson library today says they have 44 million documents, which would be 44 million pieces of paper. What

we’re reliving here, thanks to you, is the first moment I saw these and my heart really sunk at what was ahead of me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Your heart sunk at what was ahead of you.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: We’re going to talk about Johnson, the man, in a moment. But again, on the process of your work, you’re faced with all of that.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And you seem to act on a piece of advice that an editor gave you a long time ago, turn every page.

CARO: Every page. That was my first piece of advice. I had never done an investigative work before. And by accident, I was thrown into something

and faced with a whole room full of files from the Federal Aviation Agency, and I fell in love that night. I really loved doing the files. I wrote

this memo, I left it for the real reporters. And then next Monday, the managing editor, who’s a tough old guy out of the ’20s, called his — his

secretary called and said, “Alan wanted to see you right away,” I said to Ina, “Thank god we didn’t move. I’m going to be fired.

AMANPOUR: Ina, your wife?

CARO: Ina my wife.

AMANPOUR: Yes. Who was also your collaborator?

CARO: My — the sole — she’s the whole team. She’s the only person besides myself that I’ve ever trusted to do research.

AMANPOUR: So, you both do research together?

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Which is pretty amazing. But again, turn every page. I mean, that’s a huge — literally when I watched that clip, and I’m a pretty

thorough journalist.

CARO: Right.

AMANPOUR: I haven’t written books but I’m a pretty through journalist. The idea of going through that amount of information is truly daunting.

CARO: But you find — you know, if you turn — if you follow his advice and you try to turn every page, not in all those boxes but in the subject

that you’re talking about, you can find stuff like the secret of how Lyndon Johnson — he comes to Washington when he’s 29, and he has — he’s a junior

Congressman, he has no power. All of a sudden, something changes. You see this as you’re going through the letters.

In the beginning of the first three years, he’s writing to committee chairman, “Please give me five minutes of your time.” After October 1940,

they’re writing him, “Please.” So, I said to Tommy Corcoran, who is this old Washington fixer, I said, “What happened in October 1940?” He said,

“Money, kid. Money.” But he said, “You’re never going to be able to write about that, kid.” I said, “Why not?” He said, “Because Lyndon Johnson

never put anything in writing.”

So, I’m remembering this advice I got and I said, “Well, in those boxes that cover this period, I’m going to turn every page.” There’s one

innocuous letter, you know, you sit there and you say, “I’m just wasting another three weeks of my life.” And then all of a sudden, he did put

something in writing.

AMANPOUR: It’s really interesting because just the way you recount this and the forensic way you get to that, by going through these enormous boxes

just to find this one thing, I mean, that’s a lot of dedication. I mean, obviously, that’s what separates you from the boys and what’s made you the

go-to biographer, certainly on your two major, major subjects.

I guess, for you, there was no other way to do it because you said that you don’t believe in truth necessarily, exists but what do you believe?

CARO: Well, I believe there are a lot of facts and the more facts you get, the closer you come to whatever truth there is.

AMANPOUR: And that’s the only way to do it?

CARO: Well, for whatever reason, that’s the way I — something in me, that’s the only way I can do it. When I was a reporter, I couldn’t stand

to write a story when I still had a question to ask.

AMANPOUR: And I read, in terms of questions, your — sort of your questioning, you’ve taken a few tricks from literary sort of heroes and

characters, right?

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: From George Smiley —

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — and John Le Carre.

CARO: Exactly.

AMANPOUR: From Siminon’s Magret (ph).

CARO: Marget (ph). Yes.

AMANPOUR: What is it that you took from those literary figures?

CARO: Well, I took from them that when they want somebody to talk, they shut up. So, if you looked at my notebooks, you’d see a lot of — I write,

S.U., that means, shut up. That means if you don’t say anything, maybe this guy you’re interviewing will feel the need to fill the silence and

tell you something he didn’t really want to tell you.

AMANPOUR: So, you were telling S.U. to yourself? That was your memo to self all the time.

CARO: Yes. Yes.

AMANPOUR: See, that’s pretty extraordinary because I’m sure I’m guilty and many, many certainly TV interviewers are guilty of talking too much.

CARO: Well, not you.

AMANPOUR: He says.

CARO: Others.

AMANPOUR: But is it difficult to S.U.? I mean, did you have to control yourself?

CARO: Oh, yes. That’s why I write it down. Because I have the urge to talk. You ask a question, maybe it’s a tough question, the guy’s not —

doesn’t want to answer it. There’s a silence. You want to break it because you’re human. I write, instead of breaking it, I write S.U., that

reminds me to shut up. And you’d be amazed — I mean, you’re a great interviewer. You’d be amazed at how many times, after a while, he tells

you what you want to know.

AMANPOUR: You took on Robert Moses. He was your first big character.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And he, of course, is the master builder of New York, he created New York as we know it —

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — starting in the middle of the 20th century. What was it about him and about delving into him? I mean, it’s kind of a dry topic.

CARO: Here was a guy who was — we live in a democracy. So, supposedly, power comes from the ballot box, from the votes we cast. Here is a guy who

was never elected to anything in his life. He had more power than any mayor, more power than any governor, more power than any mayor and governor

combined, and he held this power for 44 years. Half a century.

You know, if you drive on a highway in and around New York, they’re all built by the same man. And it suddenly occurred to me, “I don’t understand

where he got this power [13:10:00] and neither does anybody else.” And that’s why I set out to write a book. I didn’t set out to write just a

biography of Robert Moses, I wanted to know what was the form of power that he created.

AMANPOUR: But how did he do it? I mean, there were, obviously, like in my development, that we see even today, you know, there’s some neighborhoods

that have to be razed to the ground, some, you know, real people’s everyday lives are disrupted in the name of progress, in the name of development.

CARO: He built 627 miles of road. I decided to take one mile that he ran through a neighborhood in the Bronx called East Tremont and see what the

human cost of that was. It was so sad because it was — to me, because it was a neighborhood, people had — they were not well off. They were mostly

Jewish with some Irish and some German. As long as they had their community, they had a nice life.

I would go to interview them where he had thrown them out to, 15,000 people, co-op city, little apartments, living with their kids.

AMANPOUR: You’re talking about areas of the city here in New York?

CARO: Area — I’m sorry. Areas —

AMANPOUR: Yes. No, no. It’s okay.

CARO: — of the city. And you know, in my notebooks, the word that’s written because they said it to me, I heard it over and over, is lonely.

You know? And I feel no one ever lies about that word. If you say lonely, you’re lonely.

AMANPOUR: Well, I tell you, and it’s a very, very big issue today and some of these developments are not helping in the loneliness epidemic because

community, now we know, is vital, and to break up communities is very, very difficult.

I wonder, did you find personal financial pressure in taking this long to write a book? I mean, how much did an advance cover?

CARO: I had — I used to kid around that Ina and I, I had the smallest — the world’s smallest advance, it was $5,000, of which they gave me $2,500.

After about four — we were — you know — so, I got a grant. That got us through one year. Then we had no money. So, we sold our house on Long

Island. That was before the real estate boom. So, we cleared $25,000. That got us through a second year. And then there were just several years

of we remember as just being broke.

And after about five years, I asked my editor, you know, I had given him half the manuscript, half a million words, I said, “Can I have the other

$2,500?” He said, “Oh, no, Bob, I never forget these words. I guess you can’t understand me, we all like the book, we want you to keep going, but

nobody’s going to read a book on Robert Moses. So, you’ll have to be prepared for a very small printing.” That was the worst night for us.

AMANPOUR: And then it was beyond your wildest dreams, the printing, right?

CARO: Well, it’s — it’s — well, it wasn’t an immediate bestseller but it’s now, I think, they just told me in its 55th printing, yes.

AMANPOUR: Well, look, your best, best, bestsellers have been your volumes on Lyndon Johnson.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Those have been — you know, that is the gold standard on Lyndon Johnson. So, as you can imagine, your legions of fans had hoped that your

next book, that we would be sitting here talking about volume five, your final volume on Lyndon Johnson and the Vietnam war. But it isn’t.

CARO: No.

AMANPOUR: You didn’t do that. And there are a lot of upset people. Why not? They want that book.

CARO: Well, I didn’t take all that long look because this is — what happened was I’m writing — you know, I’m saying I get asked, you know,

about when am I going to — but I also get asked, if you followed me around a lot of times, I get asked, “What’s it like to do research? What’s it

like to interview? What can you find out from interviews? What do you — what’s it like to do — go through all these papers?” I said, “Well, you

know, I’m going to — just in case, I’m going to put some thoughts about that down.” That’s why I did this book.

AMANPOUR: So, this is a stopgap measure?

CARO: Well, it’s — in its own way, it’s about me. You know, it’s not about him, it’s about me, but it’s not a stopgap. I think if people want

to get a glimpse into how I work, what I tried to do was give them enough of a glimpse so they can tell that.

AMANPOUR: How old are you now?

CARO: 83.

AMANPOUR: And you’re still going strong. You’re still pounding out the words, you’ve done this one. Are you going to get to finish the fifth

volume?

CARO: Well, let me say I don’t focus on not being able to finish but I’m working on it. It’s well under way. And let’s say, we’re going to finish.

AMANPOUR: So, to that end, you, at one point, moved the family to Texas. Is that right?

CARO: Yes. Ina and I moved to Texas. Yes. Our son, Chase, was away at college by that time [13:15:00].

AMANPOUR: And you moved your wife and yourself to Texas just to write about Lyndon Johnson?

CARO: Well, we — I was starting to — I thought that I knew about Johnson’s youth because at the time I started these books, there were

already seven biographies of Johnson. But when I started to interview these people in the hill country, it’s so lonely and isolated. I mean, you

might get their direction to interview somebody, they’d say, “Well, you go 47 miles west of Austin, look for the cattle guard, turn left and then you

go like 30 miles, say, under unpaved road.” And you suddenly realize, “I haven’t passed a house in 30 miles.”

These people were so lonely. They were so unused to talking to strangers. And also, I wasn’t understanding them. And I said to Ina, you know, “We’re

going have to move here for — until I learn this area, move to the hill country.” Ina said, because she writes books on France because we love

Paris, she said, “Why can’t you write a biography of Napoleon?”

AMANPOUR: I love that.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: She has a good sense of humor.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: She knows you well. What did you learn from them, the people who you hadn’t understood, the people who were vital to interview to know

about your subject, Lyndon Johnson?

CARO: Well, you learn two things, really. You learn, on the one hand, how ruthless he was, even as a young man in college, blackmailing a young woman

who was running for the student council to get her out of the race because of some indiscreet remark that she made, you know.

On the other hand, you learn about his incredible capacity. You know, a lot of people talk about compassion. Lyndon Johnson had true compassion,

but he had something that’s even rarer. He had the ability to turn compassion into governmental laws that help people. So, this was an area

without electricity when I — we were still talking to the women who had to live their lives without electricity.

He gets — he runs for Congress, he — the women were all bent and stooped. You know what his line was when he ran for Congress? He said, “If you vote

for me, you won’t look like your mother looks.” And it worked. And he brought them electricity. And you really said, if you’re — you know, he

said, “This is impossible.” You know, there’s not a dam built to bring electricity, he’s got to get the dam built, he’s got to get the rural

electrification administration to lay thousands and thousands of lines to these lonely folks, and he did it. Amazing thing.

AMANPOUR: Have you ever seen the likes of that kind of governmental genius since?

CARO: Since? No.

AMANPOUR: I mean, I know you don’t like to talk about politics, but I wonder if you have one sentence about why the system seems to be broken

today. We always hear various presidents want to talk about infrastructure, want to do the right thing and yes, it’s — yet, it’s very

difficult if not impossible to do.

CARO: Well, when you look at — it is, you know, the Senate is whole — I’d wrote a whole book on how the Senate works because it’s a whole

different world. And Lyndon Johnson found ways — you know, the leader before Johnson, the Senate hadn’t worked. Since the days of Webster, Clay

and Calhoun, that’s the 1850s, the Senate hadn’t worked, same dysfunctional mess it is today until he becomes majority leader in 1955.

Immediately, he becomes a majority leader the Senate becomes the center of governmental creativity and ingenuity and energy. It’s not Eisenhower’s

civil rights bill, it’s Lyndon Johnson’s civil rights bill. He leaves to become vice president after six years. For six years, the Senate worked.

Immediately, the Senate is the same dysfunctional mess as it is today, and it stayed that way.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you about interviewing his brother and getting to the heart of the family story through Sam Houston Johnson, I believe.

CARO: Johnson. Yes. Yes.

AMANPOUR: And at one point, you take him to, I think, the family house and —

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — you sit him around the family table —

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — in his childhood position by his own —

CARO: Right.

AMANPOUR: — next to his own father.

CARO: Yes. Because by that time, I knew that whatever made Lyndon Johnson this incredible human being, a lot of it had to do with his relationship

with his father who was a very respected legislator and then failed and they lost the Johnson ranch and Johnson grew up the rest of his boyhood in

real poverty, where they were worried every month that the bank was going to take their house away.

So, Sam Houston was hard to get to talk. So, I persuaded the National Park Service to let us go into the Johnson family boyhood home which was

recreated just as it was when they were kids, after the tourists were gone. And I took him in around dinnertime, because I knew it was at dinnertime

that the father [13:20:00] and Lyndon would have these horrible arguments.

And I sat behind him because I didn’t want him to see — I wanted him to feel like he was a kid again. And then I asked him, “Tell me what it was

like at dinner,” and the things that poured — and then at the end of my — and at the end of this, I said to him, “Now — ” because he had recreated

an argument between his father and Lyndon, and at the end of it, I said, “Now, Sam Houston, tell me all those wonderful stories that you told me and

all his friends told me, just give me a few more details.” There’s this long silence, and then Sam Houston says, “I can’t.” And I said, “Why not?”

And he said, “Because they never happened.”

AMANPOUR: That’s amazing. That is an amazing story. So, we’ve talked a lot about Lyndon Johnson’s successes. I guess the big failure was Vietnam.

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And this is the book that you are yet to complete?

CARO: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What are we going to learn about that, that we don’t know?

CARO: You ask great questions. What I hope people will learn, what I’m trying to show is how does a great nation get into a mess like this. You

say, he sent almost 600,000 — think of this, 600,000 men to fight in a jungle war in Asia, half the world away. It goes on for years. He dropped

more bombs on Vietnam than we dropped on Germany. I mean, this is a, you know, a rural country.

I hope — I’m trying. I don’t say I’m going to succeed. I’m trying to show how we went down this terrible path.

AMANPOUR: What would you say, remembering the cub reporter, Robert Caro, that you were in the ’50s, what would you tell that person and any of us

about what you have learned about power, political power and how it’s wielded and the people who wield it?

CARO: Well, I don’t know — I tell you something. I’d rather approach this saying what have I learned about writing about power. I learned if

there’s not enough to write about the powerful men who wield it, you have to write also about the powerless. What’s the effect on the people without

power who are affected by government, either their lives are changed for the better or for the worse, either Robert Moses or Lyndon Johnson brought

them something or if they stood in their way, ruined them. And I feel that you have to show, as I said, not just the powerful but the powerless,

otherwise books about power are somewhat incomplete.

AMANPOUR: That’s marvelous. That’s a really, really, really important lesson. Robert Caro, thank you very much indeed.

CARO: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: It’s always a pleasure.

CARO: Very nice. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Thank you very much.

CARO: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Now, on any list of masterful political power players, Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu ranks right up there near the top. And

now, as the clock ticks closer to the Israeli election, the betting is that Israelis will reelect Netanyahu for a fourth consecutive term. That’s

despite him facing indictment for multiple counts of bribery and fraud.

The polls show a tight race. So, let’s dive into the psyche of the Israeli people right now with my next guest, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, is a prominent

Israeli author and psychologist whose work explores the many currents and fault lines in Israeli society.

From Tel Aviv, she tells me why she thinks Netanyahu has integrated his own political narrative into Israel’s story so successfully.

Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, welcome to the program.

AYELET GUNDAR-GOSHEN, CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGIST: Hello, good to be here.

AMANPOUR: I’m really fascinated by your specific take on your own society, because you’re an author and a psychologist and you write very deeply about

the society you live in without being overly political. I just want to start by putting your country, Israel, in the psychologist’s chair, it’s

the patient. What is your professional diagnosis?

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Well, I think if I had to see Israel as a patient, then I would say this patient suffers from severe post-traumatic stress disorder.

I mean, you have a nation that suffered a severe trauma, not just talking about the trauma of the holocaust, I’m talking about the complex trauma of

2,000 years of exile. And then, even though the situation changed and the trauma is no longer present at the moment, we still feel that the trauma is

here right now.

So, it is if the past is occurring again and again, even though the real situation is very much different than what it used to be. We’re no longer

in existential threat as we were in Second World War but we still [13:25:00] feel that we suffer from this threat. And this shapes the whole

way we act.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s ask you to tell us why this is the case, if we are no longer, as you say, in that particular kind of existential threat, then why

do Israelis fear so much and why do they believe that they’re under existential threat?

So, you have said, and it’s true, Israel has one of the greatest stories ever told, from Exodus to today, and you’ve told, “HARDtalk,” for instance,

other interviewers, “An objective fact can be turned into a myth and then later into a story, not told by professional storytellers but by

politicians in order to keep reality as it is right now.” Explain what you are trying to say.

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Well, I think if you today’s greatest Israel’s greatest storyteller, it wouldn’t be authors like Amos Oz or David Grossman, it

would be our prime minister, it would be Benjamin Netanyahu. He’s the best storyteller of our time. And he’s telling the Israeli public this very

compelling narrative. And I think it’s compelling because it’s a very simple narrative, you know, it’s like the kids’ stories that I read to my

little kids.

You have the ultimate good being the Israelis, you have the ultimate bad being the Palestinians, this story views the Palestinians as a sort of

reincarnation of previous trauma, so that we had king pharaoh and then we had Hitler and now, we have them. And it’s a very compelling story but

this is not — this is not reality. Reality is much more complex than that.

And in reality, the Israeli people, I mean, we’re still a victim right now but we are victims of our own anxieties and of our own fear. I think we

are now the victims of the fact that we don’t try to initiate a peace process that even the word peace is, today, considered as a naive word. We

don’t even say the word, peace, anymore. We say an agreement.

So, I think Netanyahu did a very good job in delegitimizing the Israeli left and the idea that you could actually try to negotiate and to solve

this conflict rather than to relive it again and again and again.

AMANPOUR: You have also said, and you liken your writing, “Almost to telling a friend that they have food stuck in their teeth,” in other words

that you’re trying to tell a story not to attack your nation and your state, but actually to be a good friend. And yet, you are called a traitor

by those who don’t believe what you’re pointing out is reasonable, that what you’re doing is simply attacking the State of Israel.

What is the — you’ve said Israel is in a state of severe PTSD, but do you feel you are writing a narrative that does not comport to the way the

majority of Israelis feel and believe today?

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: I think we’re trying to tell a story which is far more complicated than the one of Netanyahu, but also than the one portrayed by

BDS. We usually — people go for stories which are really like the Disney film villains, you know. You have the ultimate good and the ultimate evil.

And Netanyahu would say that the good is us and the evil is them. And then some parts of the BDS who that talk about, you know, determination of the

entire Israeli State say the whole Israeli State, not just the occupation, is the ultimate colonizing evil.

And I’m sorry. I know it goes very well in cinema but I think real life is more complicated than that, and we’re trying to suggest a much more

complicated narrative. But right now, we’re failing to make people take this leap of faith and come back into negotiating.

And I think perhaps one of the reasons is that people in the left are viewed today by many other people in the Israeli society because of

Netanyahu, we are viewed as traitors, as self-hating Jews, and I don’t think of myself as a traitor. On the contrary, I think that we are the

biggest patriots of this country. I think you really need to love someone in order to come and tell him that he has food stuck in his teeth or — I

always think that I can go and tell my mother that I think she did something wrong because she’s my mother and I love her. You wouldn’t try

to argue or fight with someone that you don’t deeply care about.

In a way, I feel it’s like if your friend was driving a car while he’s drunk, then you would do whatever you can to make him stop driving the car

over a cliff. And right now, the entire state is being driven over to a cliff by people who drank too much of propaganda, you know, fanatic

propaganda.

[13:30:00}

AMANPOUR: You know, I just want to bring up this quote, Amos Oz said, “The core of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a clash between right and

right. And often, it’s a clash between wrong and wrong.” And you have explained, you know, in your own metaphorical way what that means.

But it’s so interesting what you say because it leads to the topic, for instance, of your latest book, “The Liar,” in which you talk about a rape

and you — that is the central part of the beginning of your book and it’s a false accusation.

Tell me why you wrote that, why that was the nugget of your book, particularly in this era.

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Well, Liar is based on a real story that I heard of an Eritrean migrant who was accused by an Israeli girl of sexually assaulting

her. And first, she was hugged by everyone because she was considered, you know, this hero and then when she eventually confessed that this didn’t

really happen, she was denounced by everyone who first hugged her.

And when I heard this story, I thought, this is too easy, you know, to give the collective hug to the victor and then to call this lady a monster a

moment after we learn the truth because maybe she’s not a monster, maybe she’s just a person who got confused. I mean, maybe people lie not

necessarily because they’re bad but because they can’t handle the truth.

And being an author, you know, I always try not to judge my characters, but you really try to understand them. So when I wrote “Liar,” I asked myself

why is it that people make up such lies, not just this real case of the girl who made up this story about a sexual assault.

But also, I mean, all people lie. Lying is such a terrible social crime if you call somebody a liar, it’s a huge insult. But then again, we all lie

on a daily basis.

And I’m very interested in this ambiguity. How can something be so bad but at the same time be so present in our everyday lives?

AMANPOUR: Well, it is extraordinary because you did ask a lot of people if they remembered their first lies. And do you remember yours? What was your

first lie?

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Wow, my first one. I’m not sure I remember my first one. I think there were so many after that and I forgot my first one.

But one of the biggest lies, I think, I told as a child was I grew up in a neighborhood in Tel Aviv where you had a whole lot of Holocaust survivors

and most of the kids had a grandparent or a grandmother who was a Holocaust survivor and they came to the school and they told us the stories of how

they survived the camps.

And you know, being a very young child and not really understanding what it was that I heard, I actually remember myself feeling jealous, had a best

friend who had her grandmother surviving Auschwitz and my grandparents didn’t.

I mean we had family members in the Holocaust but nobody from the first circle and I ended up blurting out that I do have a grandmother who fought

the Nazis and I took it a little bit too far. She didn’t just escape Auschwitz in my story, she also killed a few German soldiers. I think it

was one of the biggest lies I ever told as a child.

AMANPOUR: It’s really revealing. But what happened? What did your grandmother say? I mean you must have been found out.

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Yes, I was. I was caught very briefly afterwards because the story was so good that they asked me to bring her to class to share the

story, to give a testimony in front of everyone, to tell them this.

So I had to tell her what happened and she was obviously furious because she knew this was not just stories. This was the real life and experience

of so many people and I used it as a story.

But I think she also really had a lot of compassion. She also understood, you know, how jealous or how lonely a child can get to make up such a lie.

And that was when she gave me my first notebook.

She gave me my notebook and she said, if you want to tell stories, you can write. You can write. You don’t say them to people. You declare them as

stories.

AMANPOUR: It’s so interesting to hear you talk about all of this. I want to bring it full circle now. Again, in terms of the lies, in terms of the

storytelling, you know, you will have an election result in a week’s time.

And I wonder if you can just sort of riff on what Gabriel Garcia Marquez wrote about truth and lies. A lie is more comfortable than doubt, more

useful than love, more lasting than truth. Do you agree and do you see that as a political narrative?

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Yes, I think, [13:35:00] you know, nations are built on stories. Stories are the glue that keeps millions of people together. You

can call these stories narratives or myths. You can call these stories lies.

And you know, sometimes these common stories that we share, they glue us together to wonderful causes, like the miracle of the foundation of Israel.

I do think it’s a miracle.

But then again, sometimes a story can be very, very dangerous. Sometimes the story that glues people together is — can turn you once again to a

victim but now you’re the victim of your own story.

AMANPOUR: Fascinating. It’s been so interesting to talk to you. Ayelet Gundar-Goshen, thank you so much indeed for joining me.

GUNDAR-GOSHEN: Thank you for having me.

AMANPOUR: Her latest book, “The Liar” will be released in the United States this September and it’s already available in the United Kingdom.

And here’s some good news for fans of American pop culture. Emilio Estevez is back in the library. Only this time, the Breakfast Club heartthrob will

not be dancing.

Estevez is the writer, director, and star of a new film called “The Public.” It’s the story of social activism and civil disobedience set in

Cincinnati, Ohio, centering on an uprising that was staged by the city’s homeless inside the public library. And our Alicia Menendez has been

speaking to Emilio Estevez about this.

ALICIA MENENDEZ, CONTRIBUTOR: So I loved this film, “The Public.” And it has a very interesting premise and arctic cold blows into Cincinnati, the

homeless population decides to occupy the public library. And what starts as an act of civil disobedience ends up becoming a very tense standoff with

the police. I imagine this was not an idea that was easy to sell.

EMILIO ESTEVEZ, ACTOR, THE PUBLIC: No, certainly not. This was an idea that actually started 12 years ago this week, as a matter of fact. It was

April 1, 2007, an article appeared in the “Los Angeles Times”. It was written by a retiring Salt Lake City librarian named Chip Ward.

And the essay was about how libraries had become de facto homeless shelters and how librarians are now tasked with being first responders and de facto

social workers. And so, it was — for me, it was an eye-opening piece and I was very moved by it.

And so I began to imagine what it would look like if the patrons decided to stage an old-fashioned ’60s sit-in, how law enforcement would react, how

the media might spin it, and how a local politician in the middle of a campaign cycle could use it for his political gain.

To your point, I would go into offices and I’ll say, don’t you understand, don’t you see, this is exactly what’s happening. And I think people just –

– they didn’t see the humor in it. They didn’t see the humanity in it.

They couldn’t imagine a movie taking place in a library, Breakfast Club being successful. And so for me, it was very frustrating and yet

ultimately, isn’t it really all about timing.

And I think the movie is way more relevant now than it would have been had we made it even five years ago. I mean we just experienced this

extraordinary polar vortex, just descended on the middle of the country, and we were watching people dying in the streets.

MENENDEZ: One of my favorite moments in the film happens pretty early on. It’s a quiet moment but I want to take a look at it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

STUART GOODSON: It’s going to be brutal the next couple of nights for sure.

JACKSON: We could all come stay at your place.

GOODSON: I would if I could.

JACKSON: You could but you won’t. No judgment here, though.

GOODSON: Look, Jackson, use it to get some food, maybe a room.

JACKSON: You’re going to offer me money and then tell me what to do with it?

GOODSON: Well, no. I was just suggesting a few things that I thought you might need. That’s all.

JACKSON: How do you know what I need? I’m messing with you, man.

MICHAEL HALL: He’s just messing with you, man.

JACKSON: With a cause.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: Michael K. Williams, the best of the best in terms of being able to hold a tense moment, pivot from drama to comedy.

ESTEVEZ: He’s so good. He’s so solid in this film. The whole cast is.

MENENDEZ: I mean incredible cast.

ESTEVEZ: He’s electric in this film.

MENENDEZ: But what I love about that exchange is it illustrates what we get wrong about homelessness.

ESTEVEZ: Well, it’s conditional giving we see in that scene, really. We need to, I think, divorce ourselves from that outcome because that’s really

none of our business.

If we’re — if we give, we give freely and we give without condition. [13:40:00] And it’s really none of our business where that individual who’s

asked for that money is going to spend it.

MENENDEZ: When the protagonist of the film is the character you play, Stuart, a white librarian, how do you avoid the trope of the white savior?

ESTEVEZ: Well, that’s a good question. We made sure that I’m surrounded by a very diverse cast. It’s a very inclusive cast. And my character

doesn’t initiate. My character follows.

This is initiated — the lockdown is initiated by Michael K. Williams who in turn doesn’t want to speak to the police. And so he inevitably uses

Stuart as the mouthpiece for the group but Stuart does not want to be in that position.

MENENDEZ: But why choose this as the project to spend 12 years on?

ESTEVEZ: This is one of those projects that it was — it’s been sort of said that, well, this is a labor of love. It was really more a labor of

purpose.

I, you know, was informed by a great deal by my father’s activism. He’s been arrested 68 times, all nonviolent civil disobedience actions for anti-

nuclear movements, for homelessness, mental health issues, and immigration.

And so he’s been out there protesting in the streets. And the movie is, you know, I would say it’s informed by those — every one of those 68

arrests. And what I mean by that is I would watch him get arrested. It was oftentimes on national television.

And my — I would sit and watch him get carted off in handcuffs, reciting the Lord’s Prayer and he looked like a lunatic. And for me, as a young

man, it was — I understood it fundamentally but I didn’t understand it spiritually until I started working on this picture.

MENENDEZ: And this film deals not only with the social activism component of this but also the politics of this issue. Let’s take a look at another

clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BILL RAMSTEAD: Why did you lie to me?

GOODMAN: Librarian’s duty is to protect the privacy of the patrons. Maybe you heard of the Connecticut Four.

RAMSTEAD: Yes, I’ve heard of the Connecticut Four. I read that appellate case when I went back to graduate school 10 years ago.

Goodson, your intellectual vanity is breathtaking. These people that you’re protecting, your patrons, is it worth it? Is it worth throwing your

life away for? Would they do the same for you?

Not on your life, pal. I’ve been working with drunks and addicts and the mentally ill for my entire career, all day, every day, and they’re not your

friends.

They don’t give two [bleep] about you. All they care about is their next hit, their next bottle, their next meal, and they will beg, borrow, and

steal to get that from you. But you already know that, don’t you?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: So good. We have not seen that Alec Baldwin in a while.

ESTEVEZ: No, I’m so proud of his performance in this film. Again, he’s been known in the last, at least, the last 15, 20 years as being a comedic

actor, 30 Rock and the “SNL” sketches that he’s been doing.

And when he said yes to this, I was thrilled because I thought, let’s get – – let’s see Alec again in a very dramatic role. Let’s remind people that

this is how we all grew up watching him. And he just sinks his teeth into this and he does an extraordinary job.

MENENDEZ: The situation ends up being a standoff with the police. What do you want viewers to take away about the relationship between the homeless

population and the police officers that try to keep them safe?

ESTEVEZ: Sure, that, you know, I think we see over and over again the criminalization of the poor and the marginalized and it’s oftentimes at the

hands of law enforcement. I think that my hope the takeaway is that audiences begin to park their bias at the door when they confront or

encounter somebody on the street, an individual experiencing homelessness who may be suffering from mental illness.

We don’t know how that person arrived at this unfortunate place in their life. But oftentimes, we assign a story to how they got there and

oftentimes that story is wrong. I’m sure you’ve had people assign a bias or bring their bias and assign a story about how they think you arrived at

a certain place. That happens to me every day.

And so let’s stop doing that to individuals experiencing homelessness. Let’s stop treating it like a condition because it’s not. It’s not a

condition. It’s a situation. And it’s a situation that we can, I think, assist in getting people out of.

MENENDEZ: It’s not just the relationship between the homeless and the police, though. It’s also the way that we in the media sometimes frame

these issues.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: What did you want the takeaway to be there?

ESTEVEZ: So, [13:45:00] oftentimes, you know, actually on the daily, almost every channel, we see that breaking news, so much so that we’re numb

to it. And I think the media oftentimes goes to, if it bleeds, it leads, and they lean into the negative.

And that’s what happens in the case of this particular reporter, Gabrielle Union. She’s not really interested in the story and if she were to peel

the layers back and to — there’s actually a bigger story there if she were to pay attention to what was really going on inside. And so therein lies

the confusion.

And, of course, in steps the politician who wants to spin it for his own political gain because he’s in the middle of an election cycle. And you

have this unholy marriage between politics and the media, which can never exist in real life, of course, but in this film, there it is. And it

exacerbates the situation.

MENENDEZ: You grew up in one of the most influential families in Hollywood and now you live in Cincinnati, which would be really easy to read as a

rejection of Hollywood and a rejection of the way you were raised.

ESTEVEZ: Sure. Well, my mom was born in Cincinnati, raised across the river in Kentucky. My dad was born in Dayton. So they were born 45

minutes apart.

Essentially, they met here in New York in 1960 and have been together ever since. And what I love about Cincinnati is it reminds me of that New York.

I moved out of New York in 1969 and it was a city that I never wanted to leave. I loved it here. I couldn’t imagine myself living anywhere else.

When I started going back to Cincinnati about 10 years ago, I said, wow, this feels like New York, 1969. It feels affordable, right, for starters.

And it feels — it felt very familiar to me. And it’s — I would say that it’s not necessarily a rejection of Hollywood. I would say it’s just a —

it’s a quality of life issue for me.

MENENDEZ: I also think people are craving stories that don’t happen in L.A. and New York and Chicago.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right. That’s right. You know, and we tend to call them the flyover states. I call them the United States and I drive a lot. I’m

a big driver. I mean —

MENENDEZ: Yes, you drove yourself to one of the film festivals in Canada.

ESTEVEZ: I did. I drove to Toronto. It was only a four-hour trip but I’ve made — I’ve got a 12-year-old car and it has about 280,000 miles on

it. I’ve driven probably close to a million and a half miles in the United States alone.

I make these long pilgrimages Across the Midwest and the South and end up in cities that most people have never heard of, towns people have never

heard of, and really dig into those and spend time and get to know the people, get to know — Omaha, Nebraska.

I love Omaha. They have one of the best farmers markets I’ve ever experienced in my life. Lawrence, Kansas, Marfa, Texas, some of these

small towns that just have so much going on and we miss all that, of course, from 30,000 feet.

MENENDEZ: For someone who was not driven by fame, you found a lot of commercial success.

ESTEVEZ: Right.

MENENDEZ: The Breakfast Club, St. Elmo’s Fire, how have all of these experiences led to where you are today?

ESTEVEZ: Everything in your past informs where you ultimately arrive. I did do a lot of very commercial films. Oftentimes, I would do them for the

wrong reasons or I would be talked into doing them.

About 20 years ago, I made a left turn and I decided to make movies for me rather than for the studios. And that comes with a great cost, oftentimes

financial and personal and — but I couldn’t continue seeing a resume that was not reflective of who I am.

MENENDEZ: Let’s talk about the way the film that you worked on with your father, what was that experience like?

ESTEVEZ: Well, any time you get to work with family, it’s really a double- edged sword.

MENENDEZ: I was about to say.

ESTEVEZ: Because you know how to push their buttons because you helped build the machine, right? So to be in Spain where my family came from,

especially my father’s side, from the north of Spain, we are Gallegos, we’re from the area of Galicia, it was a real family affair to make that

film.

But perhaps even as equally important is the fact that the film has inspired tens of thousands of people to get off their couch and go walk 500

miles.

MENENDEZ: Just for someone who hasn’t seen it, just briefly tell me what “The Way” is about.

ESTEVEZ: Sure. “The Way”, it’s about a father who loses his son, who’s been out traveling the world. He left school and decided, [13:50:00] I

need to see the world rather than just simply study about it.

And on the Camino de Santiago, he steps off the path in inclement weather and dies. The news travels back to the United States, my father, who plays

the lead character, gets news of this, goes over to Spain to retrieve the body, to bring it home for — to the United States for burial and instead

is inspired to do the Camino on behalf of his son.

And he goes off with no training, no idea what he’s doing. And along this journey, he meets three other individuals and off to Santiago de Compostela

they go where pilgrims and believers are told that that is where the remains of St. James the Apostle are buried.

So this has been — pilgrims have been making this journey for over a thousand years but no one’s ever really made a movie about it until we went

out, went over there in 2009 and did this.

MENENDEZ: It’s the 30th anniversary of The Breakfast Club. I want to roll a clip I bet you’ve never seen before.

ESTEVEZ: Probably not, no.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREW: I said, leave her alone.

BENDER: You going to make me?

ANDREW: Yeah.

BENDER: You and how many of your friends?

ANDREW: Just me. Just you and me. Two hits. Me hitting you, you hitting the floor. Any time you’re ready, pal.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: Well, you still got the hoodie.

ESTEVEZ: He did hit the floor, didn’t he, right?

MENENDEZ: Did you know when you were making this that it was going to be as iconic as it was?

ESTEVEZ: No idea. No. When you’re a young actor, you’re in a position oftentimes where you’re begging for work. The day that I auditioned for

Breakfast Club, I auditioned for a commercial, a T.V. show, and probably another couple of films. So you just never know what film you’re going to

— that they’re going to say yes to.

When — I met John Hughes the year before that. I auditioned for 16 Candles and I auditioned for Molly Ring Wald’s love interest. And I nailed

it and I was like, yes.

And all of a sudden, I feel a hand on my shoulder and it’s the casting director and he says, “You’re not going to get this.” I said what do you

mean? Everybody was talking about me. What are you talking about? He says, “Yeah, it’s not going to happen.” This doesn’t make any sense.

Oh, you know, what? And I was furious and he says, “Listen, I need you to get in your car, you calm down first. I need you to get in your car and

you’re going to drive over to Venice”, which is the seaside area in California, “and you’re going to audition for a film. ” “It’s an odd

film”, he says, “but that’s the one I think you’re going to get. ” And it was Repo Man.

So I brought all of that anger and all of that frustration into the audition. And I was just like, man. And all I could think about was why

and the director of Repo Man saw what I did in the room and said, I want to tap into that anger.

And so again, you never know. Repo Man is iconic for — in its own way. Breakfast Club certainly keeps on having this extraordinary lifespan.

Young people are discovering it for the first time. It’s very nostalgic for people of my age to watch and remember where they were when they first

saw it.

MENENDEZ: You have been telling stories your entire life. You’re finally at a point where you get to tell the stories that you want to tell.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: The Public is now out in the world.

ESTEVEZ: That’s right.

MENENDEZ: What’s the story you want to tell next?

ESTEVEZ: Well, you know, I’m working on a lot of different things these days. There’s — I’m talking to a company about doing a series based on

The Public because I think, again, there are thousands of stories to be told in — from the perspective of desk reference librarians.

I think that there’s a lot of potential there. And it’s a show that you could move from city to city. So the first season might start in

Cincinnati and then move the second season could be in New York or Seattle or Denver. So it’s got a lot of potential.

So that’s one thing that I’m working on. I’ve been writing a script and working on a story about immigration for about 15 years and, of course,

that’s not topical right now. So that’s something that I may be digging my teeth into as well.

MENENDEZ: Emilio, thank you so much.

ESTEVEZ: Thank you. Thank you. Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: That is it for our program tonight.

Thank you for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END