Read Transcript EXPAND

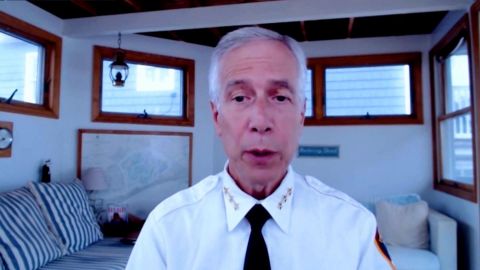

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And our next guest has an extraordinary personal story. The FDNY chief, Joseph Pfeifer, on the morning of 9/11 led his firefighters to investigate the smell of gas in Downtown Manhattan having no idea what would come next. Joe documented his account as the first fire chief at Ground Zero. And his memoir, “Ordinary Heroes.” And spoke to Hari Sreenivasan about the day everything changed.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Thanks, Christiane. Chief Joe Preifer, thank you so much for joining us. You know, it was by coincidence that there was a pair of brother filmmakers who were following you along on this day. And you were out for what seemed like a routine gas leak inspection out on the streets when this happened. Take us back to that moment when you heard the first plane.

JOSEPH PFEIFER, ASSISTANT NEW YORK FIRE CHIEF (RET.), AUTHOR, “ORDINARY HEROES”: We were at an ordinary emergency in the street, an odor of gas, which turned out to be nothing. And then, at 8:46, we heard this loud noise of a plane coming overhead, which you never hear in Manhattan because of the tall buildings. And then I see this plane racing south along the Hudson River so low that I could read on the fuselage of the plane the word American. It disappeared behind some of the taller buildings. And then, when it reappeared, I saw the plane aim and crash into the World Trade Center.

SREENIVASAN: You get in there and, as we see in the film and as you describe in the book, it is a surreal landscape because there is already broken glass everywhere on the ground. There are teams of firefighters coming in. They are kind of waiting for orders because the elevators don’t work. There are full of jet fuel and you already have burned people in the lobby. And you are giving orders to these young men to, what, start climbing the stairs, 70 flights to start rescuing people.

PFEIFER: My orders, as they came up to me, were two things. To go up and by climbing the narrow stairs, as you mention, because the elevators were not working in the North Tower. And as they were climbing up, I asked them to evacuate the building. Go up to the upper floors. We will regroup and then we’ll push up further to reduce those that were trapped by fire and by smoke.

SREENIVASAN: One of these people that you gave that order to is your little brother, Kevin.

PFEIFER: My younger brother came in a little bit before 9:00. And he came up to me without saying a word. We looked at each other wondering if each of us was going to be OK. And then, like I did for the other fire officers, I ordered him up to evacuate and rescue. He slowly turned around and took his engine company, Engine 33. And when he left the lobby, that was the last time I saw my brother, Kevin.

SREENIVASAN: There are moments in — if people haven’t seen the film or read your book, there are moments that are really difficult for people to imagine. And one of them is and one of them is the sound outside that sounds like a ton of bricks or a car has just fallen from the sky. What were those sounds?

PFEIFER: Those sounds of a wild thud and it was crashing on top of a plexiglass canopy that was at the entrance of the — to the lobby of the North Tower, and it very, very loud and it kept happened. Those sounds was the sound of people jumping. And each thud meant another life being extinguished. And I was so frustrated at one point, I ran over to the P.A. and I grabbed the mic and I asked people, I said, if you can hold on. Just hold on a little longer because we’re coming for you. We’re coming to get you. But I only could imagine what that must have been like.

SREENIVASAN: There are moments where — when the tower that you were not in collapsed. The debris comes in to where you are. You are all running. And it makes it absolutely pitch black. And by coincidence, there is a camera around. You just hear muffled voices. What were you thinking at that time?

PFEIFER: At 9:59, we heard this rumbling sound. And if you are watching on TV, you knew that was the South Tower collapsing. I had no idea what that sound was. It sounded like I was standing underneath a train trestle where a train is coming overhead and gets louder and louder and dissipates. But I thought something was crashing into the lobby, maybe down the elevator shaft or to the windows from above. Really, I thought we were the only ones in trouble. And then, the lobby goes completely black where we couldn’t see anything. And the chiefs I was with are saying, we got to get out of here. Which is a good decision. We can’t command where we couldn’t see each other. But I knew how to get out of here. I’ve been in this building hundreds of times. So, that, again, gave me a moment to deliberately think, if we have to get out of here, what do I have to do right this moment? And I got on the radio and I said, command to all units in tower one, evacuate the building.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PFEIFER: Command post from tower one to all unit, evacuate the building. Command post to all units —

(END VIDEO CLIP)

PFEIFER: So, I was pulling my firefighters out. Perhaps the first time in history, which so many people still in the building.

SREENIVASAN: You write that in the book. I mean, never in the history of the FDNY had chiefs made the decision to abandon a burning building with over a thousand people in it. And this is just minutes after. Your own — through your own frustration, you got on the public announcement system and said, we are coming. What is that moment like knowing that you are the person that gave these people hope and at the same time to help save your own firefighters and anybody else possible, you are telling them to stop doing that job and leave the building?

PFEIFER: At that moment, I still had no idea that a skyscraper just collapsed. What I was trying to do is that something really went wrong, I don’t know what it is. Let’s pull our firefighters out, regroup and then go back in. Little did I know that we only had 29 minutes between the two collapses. I want to ask a little bit about just sort of the aftermath of all this. I mean, first of all, tell us what Kevin was like. Kevin was more fun than me. He loved the sense of adventure. He had his — he shared a private plane, where he flew. A little Cessna. One propeller. And I didn’t go on the plane with him. I was one of the more cautious. But he also had an 18-foot Hobie cat. And we went sailing in the ocean and the bay around New York City. And there is a place called Avalanche, which is just at the tip of the Rockaways where out in the ocean it is like a sand bar and then there is breakers. And with the Hobie cat and with the two pontoons and the huge sail, we were surfing waves with a sailboat in the ocean screaming at the top of our lungs, go faster, go faster. So, he was definitely more into adventure. But I would join him every now and then, at least in the sailing.

SREENIVASAN: He was one of so many of the firefighters that you knew that you lost. You were only one of four surviving battalion chiefs. I mean, this practically wiped out some of the senior leadership in the FDNY in just one event.

PFEIFER: We lost 19 battalion chiefs that day. We lost our chief of department. A number of assistant chiefs. We lost the top of the department. And not only did we have to rebuild the department, but in the moment, we had to build a command structure from nothing because our top leaders were all killed. And what I saw was our deputy chiefs taking command just by the virtue of who they are. And the site was divided into four quadrants. And I can remember people hearing their voices from different quadrants and people trusting them. So, command was established are from the bottom up, not from the top down, because they were all dead.

SREENIVASAN: What is hard to imagine is the layers of trauma that the firefighters and the first responders were dealing with. Because it wasn’t just the singular event on that specific day. For weeks and weeks and months there were firefighters, including yourself, spending at times 18 hours a day looking for their loved ones. You looking for your brother and finding all kinds of things that I don’t think most of us even want in our memories.

PFEIFER: Certainly, the months after, and we spent nine months at the site, it wasn’t closed until May 30, 2002 when we were down literally at the bottom of the pile. But I think we go through a process of resilience. And not just the first responders and the firefighters, but everybody. And the first thing is coming together. For us, it was the fire house. It felt comfortable being with fellow firefighters. But we also saw in the street people coming together and making a makeshift memorial of candles and flowers, and pictures of lost loved ones because we didn’t want to go through this trauma alone. And then, what we do is like we’re doing today. We tell stories. And for me it was reflecting on the past. But we can’t stay there. We have to envision a new future, to turn those traumatic memories into hope. And for me, that was working in the fire department with a new purpose, to be their chief of counterterrorism and emergency preparedness. A title which I literally made up. It didn’t exist before. So, that we can work with multiple agencies. So, I think those things is what we went through after 9/11 and so many of our firefighters went through that process, as well as the people throughout the country.

SREENIVASAN: If you don’t mind, can you tell me what is the process like when they’ve found your brother? What went through you, what happened on the site?

PFEIFER: It’s a very personal story. On Super Bowl Sunday 2002, I was called to the site. I happened to be working that day, by chance. And they wouldn’t tell me where I was going. Which is kind of strange. Or what I was going to do, rather. But I knew, since they didn’t tell me, that they found my brother. And I came to the site. And they had him in a Stokes stretcher. And they knew it was Kevin because on the back of his turnout coat it said Pfeifer. And there was an American flag covering it. And myself and members pulled from Engine 33, we carried him out of the pit of Ground Zero into a waiting balance. And I could remember being in that ambulance and it was the saddest day of my life sitting next to him in the — on the squad bench while he was on the stretcher. And I remember tears running down my face and seeing the engine with flashing lights behind the ambulance in the spot my brother used to sit. But then, all of a sudden, I felt this sense of warmth, almost like a warm breeze. And I started to remember the times we sailed together. And I went from this intense sadness to memories of joy. And that is how I remember my brother. And I’m very fortunate that I had that opportunity to have that long ambulance ride from Ground Zero to the morgue at Bellevue Hospital.

SREENIVASAN: It seems for a lot of people that that was the last time that Americans set aside politics genuinely and came together for something. And we’ve had multiple presidents and we’ve had this war that’s gone on for so long. And we’ve just had a lot of people tearing each other down. What can you say from your life experience about how you have survived this, how you have stayed optimistic through this that we can learn from, this resilience that you have? How do we get some of that?

PFEIFER: I think we get it by trying to connect back to that spirit we felt 20 years ago. All of us felt this sense of unity, of nationalism, of actually being part of a global community. And it wasn’t just a thought in our minds, we felt it in our hearts. And I think this 20th anniversary, more than any other anniversary, I get the sense, since we’re so fragmented now, that we want to come back to that spirit that we can do this together. I mean, we’re going to face other terrorist events, climate change events, the pandemic we’re in. And I think the anniversary is a moment for us to feel that sense of unity and take it from 20 years ago and to apply it today and the to make a difference in each other’s lives.

SREENIVASAN: Chief Joe Pfeifer, thanks so much for sharing your story. And our condolences to your family.

PFEIFER: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

Fmr. Afghan Ambassador to the United States Roya Rahmani, foreign policy expert Lawrence Wilkerson, and retired FDNY Assistant Chief Joe Pfeifer each reflect on the 20th anniversary of 9/11.

LEARN MORE