Read Transcript EXPAND

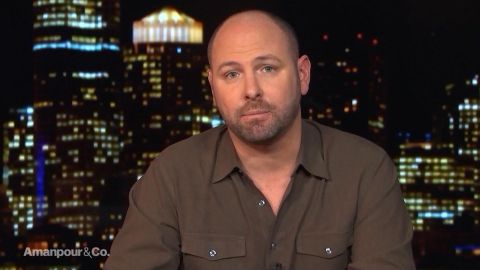

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon, owner of “The Washington Post” and richest man on the planet, is now the subject of a documentary. The documentary filmmaker James Jacoby has done “Amazon Empire: The Rise and Reign of Jeff Bezos.” It looks at one of the most influential economic and cultural forces in the world.And Jacoby sat down to talk down with our Hari Sreenivasan to talk whether and how the Bezos machine should be reined in.

HARI SREENIVASAN: You go into the archives, so to speak, at how Amazon was founded. And, there, what’s interesting is, even when they were just an online bookseller, you point out that they recognized the value of data.

JAMES JACOBY, DIRECTOR, “AMAZON EMPIRE: THE RISE AND REIGN OF JEFF BEZOS”: Absolutely. So, Jeff Bezos came out of a background in computer science and in engineering. He had worked on Wall Street before founding Amazon at a — what’s called a quantitative hedge fund, basically using data to make trading decisions and figure out trading opportunities, and so really saw the value of data and approaches things like a quant, like a real data- minded person. And he brought that mentality to Amazon and has — really, that kind of imbues the company’s ethos. It’s all about the data. It’s all about understanding consumer behavior online. It’s all about the idea that, in the 21st century economy, the company with the most data that crunches that data is ultimately going to win.

SREENIVASAN: We think a lot about Facebook when we see the word data: Oh, they know my likes and my dislikes. What kind of information does Amazon have about its customers?

JACOBY: Well, it runs the gamut. For instance, I mean, they essentially track what you do on the Amazon site. So, that’s not just what you buy. It’s what you looked at and didn’t buy, which is extremely valuable data, because they know what you’re interested in, even though you didn’t pull the trigger on something. They can see what you stopped at on the site. They have had that capacity for a very long time. They do it, they say, in the name of giving you more of what you want. It’s different than Facebook, which is trying to sell targeted advertisements to you or political messaging. But, when it comes to Amazon, they’re getting into the targeted advertising business. They also have Alexa, devices, these Echo devices, where they’re gathering data on what you ask your Alexa, what your habits are, what time of day you do certain things or don’t do certain things, and starting to get into the realm of detecting things about voice and what — how your voice sounds. So, they have many different means of gathering data on us. It’s not entirely clear yet as to how they’re going to use all that data, but, certainly, the incentive is to use it in ways that make them more money.

SREENIVASAN: You had a chance to sit down with some of the employees there. There’s almost 800,000 people that work for Amazon now. Most of them are employed in what they call the fulfillment centers, what we would look at as the warehouse where all these things are stocked. What is the core grievance that the employees that you spoke with had?

JACOBY: The core grievance is generally about the rate of work. These are really grueling jobs. And it’s something — we spoke to dozens of workers, current and former, around the country. And they all talk about the grueling pace of work. It’s essentially keeping up with the machine. I mean, for Prime subscribers, there are 150 million of them out there who are looking to get their packages delivered in one day or two days. There’s a whole system that’s partially automated, but a lot of human beings that are picking and packing those items that are getting to your doorstep. And the people that are doing that work, it’s a sort of relentless pace of work. On the other hand, these jobs pay better than a lot of other equivalent jobs. They’re $15-an-hour jobs, which is, as Amazon would point out, double the national minimum wage, and they offer benefits. So, there — it’s kind of a mixed bag. I mean, the main grievance is not necessarily about wages or benefits. It’s much more about the fact that you can’t really stay in these jobs very long. You will kind of burn out quickly, and there isn’t necessarily an opportunity at Amazon to move up.

SREENIVASAN: You pointed this out to the company. You said, hey, there’s people there that feel like they’re being treated like robots. What was the company’s response?

JACOBY: The company’s response was, well, there’s a lot of people that show up for work every day at Amazon and — to work in these fulfillment centers, and that that must indicate something, that these workers are — are relatively happy. And they also point out that the benefits are — are good and that the pay is better than the national minimum wage averages, and that they’re reinvesting in their work force, to the tune of nearly a billion dollars, to try to upskill these workers. So I think that they — they kind of answered the questions about workers feeling like robots by saying, well, there are some perks of the job as well.

SREENIVASAN: Now, Jeff Bezos did not sit down for this film, but you did have access to several different high-level executives in the company. What are your overall thoughts after speaking to them?

JACOBY: They granted us extraordinary access to a number of members of the so-called S-team. That’s sort of Jeff Bezos’ inner circle of people that have been at the company for a long time and are really running the core aspects of his businesses. And they’re — they’re extraordinarily competent. They have — this company is — deserves a tremendous amount of respect for what it’s able to deliver. And a lot of us do, even unknowingly, rely on it in certain ways. PBS, its digital infrastructure is on Amazon Web Services, for instance. And that’s — that’s rather fascinating. And I found them to be open to the scrutiny that we came with of asking challenging questions. And I think we give them the time and the fairness to answer all those questions in full.

SREENIVASAN: One of the most interesting exchanges for me was one that you had with Andy Jassy. And you were asking him about a facial recognition technology that’s being used by police departments. First of all, most people don’t even understand or realize that, A, the technology exists, B, that Amazon is behind it, and, C, that they’re actually selling it to police departments.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JACOBY: There’s been all sorts of problems with policing in this country. Why allow police departments to experiment?

ANDY JASSY, CEO, AMAZON WEB SERVICES: We believe that governments and the organizations that are charged with keeping our communities safe have to have access to the most sophisticated modern technology that exists. We don’t have a large number of police departments that are using our facial Rekognition technology. And, as I said, we have never received any complaints of misuse. Let’s see if somehow they abuse the technology. They haven’t done that. And to assume that they’re going to do it, and, therefore, you shouldn’t allow them to have access to the most sophisticated technology out there, doesn’t feel like the right balance to make.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Explain what Rekognition is.

JACOBY: So, Rekognition — with a K — Rekognition is the Amazon facial recognition tool. And, essentially, what it is, is that you can upload a bunch of photographs to Amazon and — as a kind of data set. And police departments, for instance, use it with mug shots. And then they try to match suspects in order to — against that database. And Amazon’s service, its tool, helps them do that and bring the services in order to bring the time down for detectives or police officers to try to identify a suspect quickly.

SREENIVASAN: So, it’s a virtual book of mug shots that have thousands and thousands of photos.

JACOBY: That’s correct. And so a number of police departments are using it in that way. And, essentially, the service is Amazon’s. And it’s rather inexpensive for a police department to do this. And the cops we spoke to actually really love this service. There are a lot of civil libertarians that don’t love the service and, surprisingly, a number of computer scientists that we spoke, including the former head of artificial intelligence at Amazon Web Services, who basically comes out to say that she doesn’t believe that this technology is accurate enough to be put into the hands of law enforcement. And that’s something that we do challenge Andy Jassy about.

SREENIVASAN: Because researchers have figured out that the software is not so accurate when it comes to faces of people of color.

JACOBY: That’s correct. So, MIT did a study called the Gender Shades study. Some — some scientists there came up with findings. They tested Amazon’s facial recognition software. They also tested other facial recognition software that’s on the market. And they did find that, when it comes to darker skin faces, and especially women, the software was inaccurate and prone to mistakes. And this is why people like Anima Anandkumar, former chief scientist of A.I. at AWS, have come out and said that Bezos and Amazon should stop giving this tool to law enforcement until there can be public oversight or there can be further study of its accuracy.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

JACOBY: But the company continues to do so.

SREENIVASAN: There’s another product that’s become quite successful for Amazon. It’s these doorbells that people have where you just — when you press the doorbell automatically, there’s a camera that’s looking at you. And if you’re at home, you can — you can know who’s outside, right? Now, there’s a connection between these doorbells and police departments. Explain.

JACOBY: Sure. So, Amazon purchased a company called Ring, which makes these doorbell cameras that — essentially, it’s a camera on your doorstep. It also faces out toward the street, public areas, which is problematic for some. And they set up an app, essentially, called the Neighbors or the Neighborhood app, where there’s — your footage can be accessed by your community. It’s sort of the new neighborhood watch, where people can watch what’s going on. And, essentially, in order to market Ring, Amazon entered into these partnerships with police departments, where some police departments would even hand out free doorbells. Sometimes, they’d adhere to a script that Amazon and Ring gave out, basically talking points about why this is a good thing for neighborhood safety, convincing citizens to put these doorbell cameras on their doorposts, because — but this was unbeknownst to the citizens that these cops were essentially salespeople in this instance for Amazon and Ring.

SREENIVASAN: So, the incentive for the police departments is that they have access to the footage when they would like it. Let’s say, if a criminal was running past the street, they’re going to, what, ask you and say, hey, can we take a look at your footage?

JACOBY: That’s right. And they — so, essentially, what it — what the app does is, it makes it really easy for the police to access this portal that Amazon Ring set up. And, essentially, they can go, and they can easily ask someone on that portal, hey, can I get your footage from the other night? There was a report of a crime in your neighbor’s house or in your neighborhood. We’d love to see what you — what your doorbell camera caught that night. And they don’t necessarily need — they don’t need a warrant to ask for that. But it raises a number of questions about making it easy for police departments to do that. Essentially, they can just kind of click a button, and the e-mail goes out to whoever’s camera it is. And, certainly, the ACLU and other civil liberties groups are very worried about this, because, essentially, we’re not seeing — the public doesn’t have access to how those interactions are taking place. So, there are a number of people that are rather concerned about that very tight relationship between law enforcement and this kind of new unregulated surveillance network.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: We have had an incredible year. The team has invented a lot on behalf of customers. And I cannot wait to show you what we have so far

NARRATOR: So far, Limp his team has made Alexa compatible with more than 100,000 products.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: The most successful gadget that Amazon’s been selling — and it’s been a big, successful stocking stuffer for years now — is the Amazon Echo and the Echo devices. When — these are devices that are in people’s homes, what are the privacy concerns that are surrounding it? What are the problems that have happened? And the people that you have talked to who — what are their reactions? How do they live their own lives with these devices in their house?

JACOBY: The Echo devices have been extraordinarily successful for Amazon. And they have sold maybe 100 million of these devices around the world. And people speak to Alexa, this artificial intelligence, through these devices. The privacy concern really comes with the fact that it hadn’t been clearly disclosed to consumers that, when Alexa is awake, when the device is awake and listening to you, and there’s a blue light that shows you that, and you have said, Alexa, hey, asked her a question or something, once she’s awake, she’s recording. And, in some cases, those recordings are then listened to by teams of thousands of people around the world who are trying to train Alexa, the artificial intelligence, to get better at responding to commands or responding to questions. But it wasn’t clear to consumers that there would be the even the potential of a human being listening to those recordings. And it wasn’t necessarily clearly disclosed to consumers that there was a — there was — there was a recording made. So, that — even a top executive who’s head of devices admitted that, if he could go back in time and disclose that to consumers, he would do so. But he said that he thought, even if he had, it wouldn’t have affected how popular Alexa and these devices are.

SREENIVASAN: Considering how big Amazon is getting, especially in providing services to the U.S. government, is the government capable of regulating Amazon?

JACOBY: Yes, I mean, certainly. I think that there — there are concerns about Amazon’s increasing presence in Washington, D.C. They’re going to have a second headquarters there. Jeff Bezos owns “The Washington Post.” He’s got a very large presence Now in Washington, has a big mansion there, I think the largest private residence. And people are worried about the influence this kind of economic, as well as now political, influence in D.C., and whether that is a move to try to figure out ways to either get regulators on their side or any enforcers on their side. But I think there’s quite a bit of momentum in Congress to figure out a way to regulate, not just Amazon, but all the big tech companies, and figure out, one, how existing law is applicable to them and can be enforced more stringently, and, two, whether new laws should be written about data collection or what — for instance, what lines of business a company like Amazon can engage in.

SREENIVASAN: You also point out in the film that there’s been a shift philosophically with how we think about antitrust, that it used to be that we would talk about making sure that there was an even competitive landscape for companies to be able to compete, and that we would break up companies in the past that we thought were getting close to monopoly status. But, in the last 30 years, that’s changed, and we now seem to value lower prices.

JACOBY: Yes. I mean, for the past 30 years, there’s been something called the consumer welfare standard. And our enforcers, which is really the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, who are meant to patrol the economy for people that are abusing market dominance in ways that not just hurt consumers, but also may hurt competitors or small businesses that rely on their — these large dominant players. For the past 30 years, the enforcers have really looked at it in a very narrow lens of, if you’re not — if you’re using your market dominance to hurt consumers by raising prices, that’s no go, that’s no good, but if you’re using that power to kind of hurt other businesses, with the added benefit of it being low prices for consumers, then that kind of got a pass for the — for — over the years. And the FTC right now is engaged in a meaningful reexamination of its stance that it’s taken for the past few decades. And it should be interesting to see what they do.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that’s intriguing is that, while companies — technology companies like Facebook and Google have been scrutinized and have perhaps lost some trust from their consumers, the level of trust that people have in Amazon is still pretty high, and it’s bipartisan. Why is that?

JACOBY: It’s actually not just pretty high. It’s really high. I mean, Georgetown University did a study, and basically found that Amazon is the most trusted institution in America after the U.S. military. And I think a lot of the trust that they have engendered over the years is because they’re just incredibly competent at what they do, and they deliver on their promises. They literally deliver on them. And that’s how they have engendered this trust. And I think, going forward, as the — as the company ventures into things like facial recognition software, and these really high-tech things, and cloud services for the military, and these Ring cameras, and they’re kind of going full sci-fi on us, in a way that we may or may not be able to opt out of, I think that they’re testing that trust to some degree. And I think it’s going to be an important question that they will have to answer for going forward as to how good they are at safeguarding all of the data that they have got access to, and that they’re not using it to exploit their consumers, but, rather, as they claim, help them.

SREENIVASAN: James Jacoby, thanks so much for joining us.

JACOBY: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

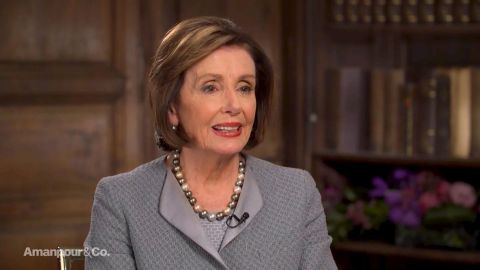

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi joins Christiane for an exclusive interview on President Trump, the impeachment trial, the 2020 election and more. In another exclusive interview, President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine discusses the infamous phone call that led to President Trump’s impeachment. Plus, filmmaker James Jacoby tells Hari about a new documentary about Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.

LEARN MORE