Read Transcript EXPAND

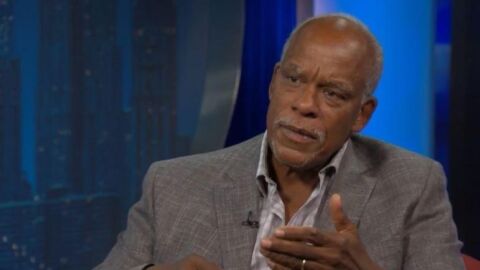

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: We turn now to our next guest, the Emmy award-winning documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson, who’s widely considered the foremost chronicler of the African-American experience. His latest work “Boss: The Black Experience in Business”, looks at the challenges faced by African-American business owners from the Civil War to the present day. And he sat down with our Walter Isaacson to discuss what drives his work, his production company, Firelight Media, and his upcoming film on jazz musician Miles Davis, which is set to release this summer.

WALTER ISAACSON: Stanley Nelson, thank you for joining us.

STANLEY NELSON, DOCUMENTARY FILMMAKER: Thank you for having me.

ISAACSON: I was blown away by watching “Boss.” And we’ve all known the problem that African-Americans have had since the Civil War in doing wealth creation. But what you show is how systematically the problem of wealth creation was even starting right after the war with the 40 acres and the mule not being a fulfilled promise. Tell me why you got onto that and what you were trying to show.

NELSON: Well I mean, I think the story of African-American businesses is just such a poignant one and that it’s a story that we don’t know, and — and the resiliency of African-Americans in, you know, fighting through that and — and starting banks and hair care companies and insurance companies and in the tech industry now. And I thought it was — I mean, I thought if I didn’t make the film, who’s going to make it? You know what I mean? And that it’s not something that people are like, oh, yes, that’s a great idea for a film, but that it could be made as a film, and that’s what we tried to do.

ISAACSON: And it seems to break a lot of stereotypes but also disrupt sort of this theme of America that we all have equal opportunity.

NELSON: Yes, I mean, I think it’s very clear that so many times — and there are so many different stories in the film where African-Americans start businesses or towns, even, and they — they’re destroyed, like, systematically. But I think that that’s — you know, just to be clear, that’s not the focus of the film. The focus really is on the starting of the business and the making of the business succeed.

ISAACSON: You talk about towns being destroyed because freed slaves and African-Americans went out west to places like Oklahoma and started their own self-contained enclave. We have a clip here, it’s a part of Tulsa called Greenwood and it’s one of my favorite parts of the movie. Let’s show it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

NARRATOR: On may 30th, 1921, the mob came to Greenwood.

MEHRSA BARADARAN, AUTHOR AND PROFESSOR: This white woman is in an elevator and this black teenager allegedly whistles at her, talks to her. She is taken to jail. A mob gathers of whites and blacks, and blacks in Tulsa are armed. They take their second amendment right seriously and they come with guns. And this is a threat. Someone fires into the crowd and the riot is born. This was not about the whistling boy in the elevator, this was about blacks becoming too economically powerful and showing that wealth in a way anyone would by creating buildings and constructing churches and having property.

SCOTT ELLSWORTH, HISTORIAN: There was a whistle that blew. And then the mass invasion and the destruction of Greenwood began.

NARRATOR: When the smoke cleared in the early morning of June 1st, 1921, Black Wall Street lay in ruins.

ELLSWORTH: This is by far the largest single incident of racial violence in all of American history.

(END VIDEOCLIP)

NELSON: Yes. I mean, I think one of the most amazing things about that clip is the footage, you know, is that we are able to tell this story because of this newly discovered footage of Greenwood, and you actually see the people in their homes. And right before what we saw is you see them kind of building the town, you know, you see them planting their gardens, you see black people on horseback herding cattle because they’re in Oklahoma and all of those things, and then you see the destruction of that, and it’s just – it’s very moving to me partially because you can really see it and you can visualize what the town was.

ISAACSON: One of the things I learned was that the first real businesses were sort of services whether it be barber shops or beauty and other things. How did that help pave the way for building of wealth?

NELSON: Well, one of the things that happened in the South was, you know, after the time of enslavement as African American became free, many times black people took up the jobs that they kind of already were doing. So you know, if I was a barber, or that was one of my duties, then I had my own barber shop. If I worked in the field, then I became a farmer. So a lot of those things led to the first businesses that African Americans had and led to a certain amount of economic freedom.

ISAACSON: What were the obstacles, though, to real wealth accumulation?

NELSON: Well, I mean, I think there were so many. I mean, at first and for a long time as we show in the film, African Americans really only sold to African Americans. You know, you could have a store that sold to black folks, but what people really don’t sometimes understand is that in most of the this country if you are even a black grocer, it was very hard to have a black grocery store that whites would frequent.

So basically for a lot of the history of the United States after the Civil War, black people were having businesses that sold to black people. And so, you know, that in some ways was limiting. You can’t borrow capital. You could not go to a bank and borrow money. That was somehow in some ways alleviated when black people started having their own banks, but in so many places in this country you couldn’t even walk into a bank, but if you could, you couldn’t get a loan.

ISAACSON: One of the obstacles seems to be the big corporations. You have a wonderful sequence of Ursula Burns who moves from being the executive’s assistant to the CEO of Xerox – to being the CEO herself, but she’s a very unusual case. Why is it that it’s hard for African Americans to become the boss?

NELSON: Well, I think, you know, there’s this ceiling above you and it’s not a glass ceiling. It’s a real ceiling. One of the things that Ursula says in the section we have on Ursula is she says it was hard for me because what this – what businesses looks at as excellence are white men. You know, that’s what they – as she says, that’s what it looks like, that’s what it sounds like, you know, that’s the model. And it’s very hard for a black person, and especially for a black woman, to, you know, fit into that model. How do you fit in it? If that’s your standard of excellence, how do you break in? People do it, but you have to be extraordinary.

ISAACSON: One of the entrepreneurs you’ve done a documentary on before and then as part of this one is Madam C.J. Walker. Tell me about who she was and how she created a business.

NELSON: Yes, so Madam C.J. Walker was a woman who, you know, pretty much started out with nothing. In the south, she started working for a woman named Annie Malone who had a company called Poro Products, a black beauty company in Chicago – out of Chicago, and Madam Walker said to herself, you know, I could do this and I could do it better. And so, Madam C.J. Walker, you know, moved to Indianapolis, started her own company, and just raised it from nothing until she had a whole series. I think it was 19 or 20 different products that she had and, again, is kind of in the Guinness Book of Records as the first woman to start with nothing and earn a million dollars.

ISAACSON: All of your documentaries on the deal with race from different angles, how does the arch of your career, how do you put those together to say, “here’s the story I’m trying to tell”?

NELSON: I feel that people should tell their own stories, that stories are richer and deeper and more meaningful and more heartfelt if they’re told by the people who live them. So I try to tell stories that I live, that I think are important. But I also think in very general terms I’m really interested in institutions and movements and things that are bigger than just, you know, the great man or woman of history.

ISAACSON: Now, the film that’s coming out soon, which I just loved what I got to see on it, is on Miles Davis.

NELSON: Right.

ISAACSON: And that seems a bit of a departure. I mean you’re doing somebody who is an artist and just wakes up every morning with his music. In fact, let’s do a clip about the importance of music to him.

NELSON: Sure.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MILES DAVIS, AMERICAN JAZZ TRUMPETER: Music has always been like a curse with me. I’ve always felt driven to play it. It’s the first thing in my life. Go to bed thinking about it and wake up thinking about it. It’s always there. It comes before everything.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

NELSON: Yes, I mean that’s just a beautiful clip. I think for me, you know, I’m a real music lover. I listen to music from the time I go to bed — the time I wake up to the time I go to bed. It’s just something that — and I’ve always wanted to do, like, a pure music film. And you know, who’s better than Miles, you know? Because one, Miles’ music is so great and so important, and I believe will last forever, but two, Miles was a really complicated individual. You know, he was really complicated, and it makes – it makes for a much richer film.

ISAACSON: He was complicated, too, in his feelings about race, right? Because he gets beaten up once by a white deputy here in New York City, and it sort of scars him for the rest of his life. There’s an anger there that’s in his music sometimes.

NELSON: Yes, I mean I think that, again, you know, Miles, there’s so many facets to Miles to understand and try to unpack. And I always say that I think before you try to unpack anybody or anything, you have to first say that, you know, different people react to different stimuli in different ways. So you might have lived, or I might’ve lived, the same thing and reacted differently. But Miles grew up – his father was dentist, and Miles grew up in East St. Louis, and they were – for the standard – for African-Americans at the time, they were rich, OK. They had a farm outside the city. Miles had a horse, you know, that he would ride. I mean, you know, Miles grew up rich, but he also grew up black in segregated America, you know, in East St. Louis. So he had all that to pack on top of it. Also, Miles was very, very dark skinned, and Miles was beautiful. So he had that going on.

ISAACSON: Let us show something about the blackness, because that blackness is an amazing part of the movie.

NELSON: Yes.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TAMMY L. KERNODLE, MUSICOLOGIST: I think the darkness of Miles Davis’ skin, instead of seeing that as a liability, he saw that as an asset. It was very different from anything that was projected on television or in movies at that time. Miles turned that into something cool, something desirable.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ISAACSON: Cool. And that’s what – it’s like the birth of cool, is what you’d call this, like, because that’s what he does with his music, is a birth of cool.

NELSON: Yes, Miles look – Miles was – we’re making the film. We’re like, “OK, so Miles is just the coolest guy that ever lived.” I mean he just is. You know, I mean, you know, with – as somebody says in the film, you know, Miles had the cars, the fast cars, the snappy clothes, you know. Miles had his clothes tailored. He had beautiful women. One of the musicians says, you know, “We not only wanted to play with Miles. We wanted to be Miles. That’s what we wanted to be.” So Miles is this – you know, has all these things going for him, but he also has this chip on his shoulder, you know. And, you know, that part of that was his reaction to the racism that he was exposed to – he was born in 1926 – racism that he was exposed to in that America. And, you know, he is that person.

ISAACSON: And he was always innovating, in a way. I mean this creativity is like, don’t stand still. Let me try a whole new form of music.

NELSON: Yes, I mean I think that’s who Miles was, you know, to our great benefit and sometimes to his own detriment, you know. I mean, you know, he breaks up groups just because he wants to do something else, you know. There’s a great scene in the film, where he asks Ron Carter – I mean he has what’s one of the greatest groups ever, and he asks Ron Carter to play electric bass. And Ron says no. Miles is like, “OK, well, then bye,” you know. I mean that’s kind of how it was with Miles, you know. It was – he had this thing where he constantly had to change. He constantly had to create. And you know, I think, again, for us, listening to it, it’s great, because he great music in so many different ways. But for him sometimes, personally it was hard.

ISAACSON: Your next big project, I think, is on the Atlantic slave trade, and you’re going to try to try to treat it as a business.

NELSON: Right. Yes, we’re working on a four-part series for PBS on the Atlantic slave trade. We’re just starting now. And I think that, you know, one of the things we wanted to try to do was say, you know, look, this was the first global business. This was a business that set so many things in motion. You know, shipping, banking, insurance, all of these things came out of the slave trade and — it’s something we never look at. So, this is a four part series on the trade, it’s not on slavery, it’s on the trade, which was a business that was in Europe, Africa, North America, South America, the Caribbean were all involved in the slave trade. So, it’s the first real global business in the world.

ISAACSON: One of the small things that you did that I find very interesting as I looked at it, was a training video you did for the Starbucks Company, of what it’s like to be in public and be black.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Especially being a teen of color, they assume that you’re doing something bad.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I feel like I’m disturbing people by just being there. Like, people feel uncomfortable when I walk in.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ISAACSON: Explain why you did that and what you conveyed there.

NELSON: Yes, well Starbucks came to me after they had the incident where the four — the two guys were arrested in Starbucks in Philly and they decided that they were going to close their stores down and kind of have a training session for the employees and they wanted to do a video. And so, what we came up with was an idea of African-Americans and other just talking to the camera about how we feel in public spaces and that so many times we don’t feel entirely welcomed and that it has it’s roots in the civil rights movement, which part — a large part of civil rights movement was to say, everybody is equal in public spaces, right? So, you could go to a public library, you can go to a park, you can go to a swimming pool, but we still, as African-Americans, don’t feel welcomed so many times when we walk into stores and other places.

ISAACSON: Did you have any reservations about working with Starbucks and to try to help smooth their situation over?

NELSON: I mean, for a second, when they called me, I wanted to meet with them, but then when I met with them I — I mean, they were totally honest about it. I mean, they had — they closed down their stores, they didn’t have to do that. I think Starbucks, in some ways they were really shaken by this and they really wanted to try to make it right. And so, I felt very comfortable in trying to help.

ISAACSON: Did we move on too quickly?

NELSON: Yes, I think so. I think — and there’s a lot more discussion to be had. I think it’s really at — it’s and important, important discussion and I learned so much from doing the film, because I didn’t know that there were things that I didn’t talk about. I didn’t ever think about the fact that I am not comfortable going into a lot of places. Or it’s not even uncomfortable, it’s that just little, you put your hand on the door and you’re like, OK, I don’t know what’s going to happen and what might happen. And I think that’s important to talk about.

ISAACSON: Name of your company is Firelight Media and it’s important for Firelight to be training a next generation, especially of African-Americans who can own the story and tell the story.

NELSON: Yes, well we have a documentary lab where we train filmmakers of color, of all races, so black, Latino, Asian, all races and we have between 10 and 15 filmmakers who are — who we mentor in the lab at the same time. There’ve been, I think, over 80 filmmakers who have graduated the lab, and these are filmmakers who are making full length films, they’ve been on all different networks, we’ve been — had multiple films at Sundance, one of our films just won an award at Sundance this year. Emmys, Peabodys, Duponts, all those things have our films have won.

ISAACSON: And where do you see it going over the next 10, 15 years?

NELSON: Our next step that we’re really pushing to do and raising money to do is to have a move for the filmmakers to make their second film. Because what we’re finding is people who have been through the lab, they win a Dupont or they won a Peabody, they win an Emmy and it’s still hard for them to get their foot in the door for that second film. So, what we want to try to do is be able to give filmmakers seed money, mentorship to get that second film made, because when I made my second film, when I made Two Dollars and a Dream, William Greaves, who was kind of my mentor said to me, well Stanley, you’ve done it twice, they can’t say it’s an accident, you’re on your way.

ISAACSON: Stanley Nelson, thank you so much for being with us.

NELSON: Thank you so much.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Norman Ornstein & Susan Glasser about Attorney General William Barr. She also speaks with Madawi Al-Rasheed about the mass execution of 37 men in Saudi Arabia. Walter Isaacson speaks with filmmaker Stanley Nelson about his latest documentary, “Boss: The Black Experience in Business.”

LEARN MORE