Read Transcript EXPAND

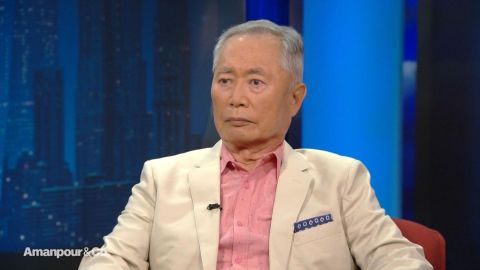

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: You may know him best as Sulu from “Star Trek” but actor and activist George Takei also has a darker story to tell. During the second World War, thousands of Americans of Japanese descent were forced from their homes and sent to internment camps. George Takei was among them and he just sat down with our Hari Sreenivasan to talk about his new memoir where he revisits this dark period in American history.

HARI SREENIVASAN: So most people remember you as Sulu from “Star Trek” but well before that, as a child, you lived through three American internment camps. What do you remember about that first day when the soldiers came knocking?

GEORGE TAKEI, AUTHOR, THEY CALLED US ENEMY: The soldiers came, pounded on our front door with their fists, a sound that I still remember. I mean I think — I thought the whole house trembled when they were pounding on the door. At gun point we were ordered out of our home, a two-bedroom home with a front yard and a back yard on Garnet Street in Los Angeles and taken to a nearby race track, Santa Anita Race Track and we were assigned a smelly horse stall to sleep in, all five of us. Three children, I was the oldest at 5-years-old, and my parents. For them, it was a degrading, humiliating, painful thing to take their three children to sleep in this narrow, smelly, I mean still had the pungent stink of horse —

SREENIVASAN: Coming from your home.

TAKEI: From our home.

SREENIVASAN: And so Santa Anita is kind of your first stop.

TAKEI: And we were there because the camps were being built during that time. We were there for about four months. And when the construction was finished, we were put on trains with armed guards, armed soldiers, at both ends of each car, and transported two-thirds of the way across the country to the swamps of Arkansas.

SREENIVASAN: How are your parents dealing with this?

TAKEI: People were despondent, depressed, angry, or fearful. And my — we were in a cleared swamp and when it rained it turned right back into a swamp. People had to make that trek to the mess hall three times a day. And for the older people, their feet would sink into the muck and they didn’t have the strength to pull their feet out. So young men had to carry them on their backs, which meant the young men’s feet sank even deeper. And so an idea came up to build a boardwalk connecting each of the barracks. And they asked my father to be the block manager and so he organized that. So my father became something of the leader of the camp. And for me, as a kid, my daddy was a block manager. He had power. He was making speeches at the end of each meal. So for me, it was an exciting — I mean as a 5-year-old child with a daddy who’s the head of the whole operation.

SREENIVASAN: There is a survey that you mentioned in the book that everybody had to take. And it’s, question number 27 and 28 are pretty interesting. Number 27 says, are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered? And then number 28 says, will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces and foreswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor to any foreign power or organization? So what were the answers to those two questions? What were the consequences?

TAKEI: Let me take you back a little further to give you the background for that.

SREENIVASAN: Yes.

TAKEI: Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, young Japanese- Americans, like all young Americans, rushed to the recruitment centers to volunteer to serve in the U.S. military. This act of patriotism, and that’s what it was, was answered with a slap on the face. They were denied military service and categorized as enemy alien. Made absolutely no sense. But it was a time of hysteria and fear and panic on the part of the United States. And they took everything from us — our bank accounts, our businesses, our homes, impoverished us, and then put us behind barbed wire fence with machine guns pointed at us. At night when we made the night runs to the latrine, search lights followed us, with no choices.

SREENIVASAN: You had not committed a crime, right?

TAKEI: No crime. In fact, they couldn’t even charge us with any crime. So there were no charges and therefore no trial. Due process, the central pillar of our justice system, simply disappeared. And a year of imprisonment under these circumstances, then they realized there’s a war time man power shortage. And here are all these young people that they could have had but accused of being enemy aliens. We were neither. How to justify drafting people out of a barbed wire prison camp? Their solution was this so-called loyalty questionnaire, which everyone over the age of 17, man or woman, 17 or 87, had to respond to. Now, can you imagine my mother? I was a kid. My brother was younger. My baby sister was now a toddler. She was being asked to bear arms to defend the United States of America.

SREENIVASAN: The country that —

TAKEI: The country that’s incarcerated us. And she is supposed to bear arms to defend that country. That was preposterous. I mean, abandon her children. Question 28. We’re American citizens. We never even thought of a loyalty to the emperor. We’re Americans. They assumed that we had a pre-existing —

SREENIVASAN: Allegiance?

TAKEI: — racial loyal —

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TAKEI: Loyalty, allegiance to the emperor.

SREENIVASAN: Right.

TAKEI: So if you answered, no, meaning I don’t have a loyalty to the emperor to foreswear that no applied to the first part of the very same sentence.

SREENIVASAN: That’s right.

TAKEI: Will you swear your loyalty to the United States? If you answered yes, meaning I do swear my loyalty to the the United States, then you were confessing that you had been loyal to the emperor and now were prepared to foreswear that and re-pledge your loyalty to the United States. It was a no win question. Yes, you lost and no, you lost.

SREENIVASAN: Your parents said no to both.

TAKEI: My parents said absolutely not. We have principles. We have intelligence. The people that are putting this together are reckless, ignorant people.

SREENIVASAN: So what happens then?

TAKEI: They were categorized as disloyal. And we had to be transferred from the Arkansas camp to another camp in Northern California right by the Oregon border called the Segregation Camp for Disloyals. This segregation camp was the classic epitome of overreaction. It had not only one barbed wire fence but two more. Three layers of barbed wire fences and a half a dozen tanks patrolling the perimeter. Tanks, they belong on a battle field. Not intimidating citizens that were goaded into outrage and put into this even more outrageous and idiotic, crushing evil circumstance.

SREENIVASAN: It’s hard for us to imagine an entire government immediately doing this to an entire population of American citizens that lived among them, right? But you talk about it in the book, the attorney general at the time, who goes on to become governor of California and a Supreme Court justice, the views he was holding, other senators were holding at the time, and what was openly said is something we would consider racist today.

TAKEI: Racist and vicious vilification. The attorney general in California at that time was a distinguished man but he was also ambitious. He had his eyes on the governor’s seat. And he saw that the single most popular issue in California at that time was the lock up the Japs issue. Lock up the japs. There’s that rhythm that we still hear today. And this attorney general, this ambitious man, saw that in order to be elected governor, he needs to be in front of that issue. And he made an amazing statement as the attorney general of the state of California. He said, we have no reports of sabotage or spying or fifth column activities by Japanese-Americans and that is ominous because the Japanese are inscrutable. You can’t tell what they’re thinking behind that placid face. So it would be prudent to lock them up before they do anything. So for this attorney, the absence of evidence was the evidence. And he became very popular, got elected governor of California, re-elected twice, served three terms, and then appointed to be the chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. His name went down in history as the liberal Supreme Court Chief Justice, Earl Warren. And he never owned up to it while he was alive. This is what we had to put up with.

SREENIVASAN: When you see the images now on T.V. of what’s happening on the southern border, what goes through your head?

TAKEI: Horror, terror, disgust, and it galvanizes me. We’ve got to put a stop to it. We are Americans. This act is not American. We know what American values are, our ideals are. We will oppose them tooth and nail and show that the United States is a humanitarian country. And we will offer our hand in aid to people that are suffering. We are Americans.

SREENIVASAN: Look, I could see a supporter of the president sitting here right now saying hey, listen. I will agree that what happened to you as an American citizen is a tragedy and a travesty but that happened to American citizens. These are not American citizens that are on our border wall. These are people who are trying to come into this country, right? I mean there are lots of people who justify what is happening right now and say that it’s different from what you went through.

TAKEI: At the core, it’s the same mentality, mindset, this sweeping characterization of people who look different. If you really understand those people that are coming here, they’re coming from places like Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador where it is sheer chaos, violence, and poverty. Some of the people — some women have seen their husbands shot right in front of their eyes and they are literally fleeing for their lives. Asylum is legal and we need to respond as human beings. Yes, they are not citizens. But we share in common with them our humanity and we have, as Americans, who feel for other people, and we have a history of doing that. The Marshall plan after the second World War, devastated Europe, in Ruins and Hungary. We gave them aid and brought their economy up. And so that contributed to a better global economy. And we have to think like that. We live in a global economy, global politics, global culture. And we need to connect to each other as human beings.

SREENIVASAN: Why do you think that this period in history, the internment, that there is a gap in understanding between generations? Why did elder Japanese people not speak about this in their families?

TAKEI: What they experienced was profoundly wounding. It was enraging. It was painful. It was anguishing. And they wanted their children to build their lives in this country without being exposed to the same thing that they did. And so they didn’t talk about it. That’s not too different from veterans of the war who didn’t want to talk about their battlefield experience with their children.

SREENIVASAN: The graph acknowledges the latest attempt you’ve made here to try to keep getting this story out, you also had a show on Broadway a few years ago and there’s also —

TAKEI: Allegiance,

SREENIVASAN: Allegiance. And there is now a program on AMC. I want to show a trailer of that real quick.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Suzuki, coming with us.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Came all the way over the ocean, we are not safe.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Fill it out. Turn it in. You just have to prove you’re a loyal American.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You ever get the feeling you’re being watched?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: There is something evil. I can feel it.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You believe in (inaudible)?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Shape shifting spirits.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Drop the weapon.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I never used to believe in the old country stuff.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Anywhere you go, it will follow you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: I think some of the directors and producers, they have had their grandparents live through this or unfortunately die in Hiroshima or other places.

TAKEI: Right.

SREENIVASAN: I mean the idea of Asian representation on T.V. is still somewhat an anomaly. I eman it is only the rare show that gets a full cast of people of color, right? And they are usually, sometimes marginalized into smaller networks or the exception not the rule on the network lineup. And here you are having been the lone Asian character really representative of the entire Asian world on “Star Trek” and here, you are just playing a part in this very rich cast.

TAKEI: And it’s starting to happen with greater frequency. This isn’t the only production. And it’s rooted in the reality of Japanese-American history here. We’ve come long ways from when I started my career back in the 1950s when the roles were all a silent servant or the comic buffoon or the evil villain. Now we’re having substantial stories like the “Terror Infamy” with its deep roots in American history. This is important because it’s an American story. I consider it my responsibility to tell this story in an effort to make the future of America a better one than the ones we’ve lived through.

SREENIVASAN: You’ve grown up and lived through eras where it would have been illegal for you to marry a white woman, much less a man.

TAKEI: My aunt was in love, this is shortly after the war ended, with a white man. It was illegal in California. We had an anti- miscegenation law but for 11 years now I’ve been married to a white dude. So, you know, we are making progress.

SREENIVASAN: George Takei, thanks so much.

AMANPOUR: Such an important conversation. Thank you for watching and goodbye from New York.

END

About This Episode EXPAND

Beto O’Rourke joins Christiane Amanpour to explain how he would combat the crisis, as well as his stance on gun control and his standing in the race for the presidential nomination. Ernesto Araújo, Brazil’s Foreign Minister, discusses the Amazon rainforest fires. George Takei sits down with Hari Sreenivasan to discuss his new memoir, “They Called Us Enemy.”

LEARN MORE