Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And we leave, though, these politics for a moment to delve into the politics of feminism with Director Greta Gerwig. In 2018, she became the fifth woman ever to be short-listed in the best director category at the Academy Awards in its 90 years for her movie “Ladybird,” an ode to mother-daughter relationships. And she continues her exploration of strong female characters with an adaptation of the Louisa May Alcott classic, “Little Women.” The inspiring story of four sisters as they come of age in the aftermath of America’s civil war. It’s a film Greta Gerwig fought to write and direct. And our Michel Martin sat down with her to find out why.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: What is it about your films that make grown women cry?

GRETA GERWIG, WRITER, DIRECTOR AND ACTOR: Oh, my goodness. I did not think that was going to be the first question. I — well, I don’t know exactly. I mean, I do know that when I’m writing and when I’m directing, I keep thinking about, what am I passionate about, passionate about what moves me, what do I want to see and I keep trying to be honest with myself about what is it that excites me. And I always know that I’m on the right track when I have this feeling of, I can’t believe no one’s made this movie. Like, there’s sort of this feeling of, has this not been done? Because I don’t know why it hasn’t been. I think it should be. And I think that there’s something of that. But I also — I don’t know. I’m a really emotional person. So, I think I have — that’s one of my —

MARTIN: Do you agree with me, though? Because when I ask my friends about —

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: — the friends, the women that I work with —

GERWIG: Yes, yes, yes.

MARTIN: — like the question is not, you know, did you cry? The question is when? Did you cry when, or did that make you cry when — you know, we’re comparing notes. And I’m thinking, wow, we are women who cover wars and we are women who cover impeachment, and we’re talking about when this movie made us cry, and I just —

GERWIG: Oh, my God.

MARTIN: Yes.

GERWIG: You know, I wish I had a better analysis of why. I don’t know. I’m glad it does. I’m glad it moves people. It moves me. So, I think you’re always trying to transmit that to the audience. I mean, I always say movies are empathy machines.

MARTIN: Why did you start making films to begin with?

GERWIG: First of all, I just wanted to be part of it, because I loved films, I loved cinema, and I just wanted to be part of it any way I could. So, I started really doing everything. I was writing, I was co-directing, I was holding the boom, I was editing, I was — because I was working on such low-budget films that everyone had to do everything all the time anyway. And then I moved into knowing that I wanted to direct later because I loved it so much, there was a feeling of wanting to be qualified and wanting to know enough that I felt that I could responsibly take charge of the set and also, responsibly get all of these people to donate their time and talents or use their time and talents, rather, for the movie, because I think I just didn’t want to go off half-baked. I wanted to really know that I was ready. So, I spent about 10 years working in movies before I directed. And it was after I had finished my script of “Ladybird” that I thought, I think this is the one, and I think, at this point, I’ve gotten all the experience I’m going to be able to get without actually doing it.

MARTIN: I was going to ask about that, because you know, like a lot of people who cover politics, you know, I’m really interested in this question of when women run and —

GERWIG: Yes, yes.

MARTIN: — when this give themselves permission to run, and there’s some research that shows that, you know, women need to be asked three times before they will commit to running.

GERWIG: Wow.

MARTIN: Whereas men, it’s once or maybe not even ever.

GERWIG: No one even — no one asked them.

MARTIN: Right, nobody even asked them. And I was just wondering for you, like when did you give yourself permission to say, I am going to be in

charge, I am going to tell the stories that I want to tell in this way? Do you remember when that clicked in for you that you had that —

GERWIG: Right.

MARTIN: — right to do that?

GERWIG: Well, it wasn’t one light bulb moment. It was an accumulation of moments. I would say it was around 30, around 30, 31, that it felt that it was time. And it was mostly because I had a script that I felt very passionately about and that I felt that I knew how to make.

MARTIN: And that was “Ladybird”?

GERWIG: And that was “Ladybird.” But — and then after that, I actually, interestingly in the chronology of my story, I had the script for “Ladybird.” I knew I wanted to make it, but it takes time to make movies. It just — getting financing, getting actors together, figuring it out. So, in the interim, I had heard that they were interested — that Sony was interested in making “Little Women,” and I told my agent he had to get me in the room because I actually had already had an idea for what I wanted to do with “Little Women.” So, before I had even directed “Ladybird,” I went in to talk to the folks at Sony, and I said, I have to write this movie and I have to direct it. And they — and I hadn’t directed anything at that point. And I think it was actually those two things, that “Little Women” and “Ladybird” for me came together at the same time, and I was — and I started to be more certain of it. I think when I told them I was going to direct “Little Women” before I directed anything, in a way, I was imagining a more brave person than I am and pretending to be them for the amount of time that I was talking to them, and then I left the room and thought, do I really have that in me? I’m not sure. But I — to your point of being asked three times, I had been — there had been a number of things. I had had three different female directors say something to me. I had Miranda July, Rebecca Miller and Sally Potter had all said something to me about directing, and —

MARTIN: What did they say?

GERWIG: Well, Sally Potter, I was asking her. She’s a great British director. And she — writer-director. And I was asking her about writing because I had been writing films. And she stopped me and said, why don’t you ask me what you really want to ask me? And I said, what do I really want to ask you? And she said, you really want to ask me about directing. I was like, how do you know? She said, you’re a terrible liar. I mean, she was basically like, it’s written all over you. You want to direct. This is why you’re asking. And the other two was more symbolic. We had talked about directing and they both — this is sort of mystical, but why not, I’m allowed to be mystical. They both gave me pairs of shoes that had — that didn’t fit them that they thought would fit me.

MARTIN: Wow.

GERWIG: And I thought, if I was writing this in a script, that’s way too obvious of a metaphor. That would be like, cut that, it’s too much. But when — by the time Miranda gave me a pair of shoes first and then Rebecca gave me a pair of shoes, and I was like, this is incredible. So, I felt like —

MARTIN: Go fill these shoes.

GERWIG: Go fill these shoes.

MARTIN: Go fill these shoes.

GERWIG: So, I felt that I had gotten signs. Then I had written this script and then the synchronicity of them being interested in “Little Women.” And so, by the time I was directing “Ladybird,” I really feel like it was an accumulation of years of building up to that point, but you know, I can’t speak to — I’ve only ever lived as a woman, I don’t know, but I felt the pressure of wanting to make sure I had groundwork for doing this art form that I love and trying to do it as best as I could.

MARTIN: Central to the book then and central to your film now is the question of what are women allowed to do?

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: What are women and girls allowed to do? What are they allowed to dream? This is a clip where Soairse Ronan as Jo is talking to her Aunt March, played by the formidable Meryl Streep, and Meryl Streep is basically schooling her as she thinks she should. And here it is. Let’s watch.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MERYL STREEP, ACTOR, “LITTLE WOMEN”: Josephine?

SOAIRSE RONAN, ACTOR, “LITTLE WOMEN”: Yes, dear.

STREEP: Is there a reason you stopped reading Belsam (ph)?

RONAN: I’m sorry. I’ll continue.

STREEP: You mind yourself, dearie. Someday you’ll need me and you’ll wish you had behaved better.

RONAN: Thank you, Aunt March, for your employment and your many kindnesses, but I intend to make my own way in the world.

STREEP: No, no one makes their own way, not really. Least of all a woman. You’ll need to marry well.

RONAN: But you are not married, Aunt March.

STREEP: Well, that’s because I’m rich.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MARTIN: Wow. Yes. Tell me about that.

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean, it feels very fresh and real, where women are basically — you know, how often is it that, you know, women are telling other women what they are allowed to be and do? I mean —

GERWIG: Right.

MARTIN: — that still happens, doesn’t it?

GERWIG: Yes, yes.

MARTIN: You know, sort of mind yourself, you know. But the whole question of what women and their — what’s the word I’m looking for, constraints —

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: — is very much a part of this.

GERWIG: It’s very much a part of this. And, you know, the character of Aunt March, which Meryl Streep did tell me she was going to be in this movie and she told me she’s going to play Aunt March, which was one of the best things anybody’s ever told me.

MARTIN: Is that — that’s how way it works?

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: I didn’t know.

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: OK.

GERWIG: We went out to lunch and she said that book meant a lot to me, I would like to play the battle axe, please write me some good lines. And I — but she had so many incredibly smart things to say. She’s not only a brilliant actress who’s — I mean, one of the best actresses who’s ever lived, she’s also wildly intelligent and really understands what the heart of something — what the heart of a story is. And we had incredibly productive conversations about this book and what it means. And I think, you know, it’s obviously funny when Aunt March says, well, I didn’t have to get married because I’m rich, but I also think Aunt March — Aunt March isn’t wrong about the world. And I think one of the lines that always moves me is she says, nobody makes their own way, not really. And I think that there is, you know, particularly this illusion of everyone’s able to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps, and that’s just not true. And it isn’t — and it — particularly for the 19th century, it wasn’t true of a woman. And I think that her constant pointing out the reality versus the idealism of Jo, I don’t think either one of them is wrong. And I think that that’s what is so fascinating to me. I think — I can’t remember which writer said this, but it’s true — a conversation between a person where one of them is definitely right and one and one of them is definitely wrong isn’t that interest. A conversation between two people who have a point is interesting because then there’s something to talk about. If there’s a rightness and a wrongness, then it’s just over.

MARTIN: Why did you want to make “Little Women” as a film so badly? Why was it so important to you?

GERWIG: Well, there were a few reasons. When I reread the book — and I had read it so much when I was young, but I probably hadn’t read it since I was 15. And then I read it again at 30, so twice as much time had passed; 15 years had passed. And when I read it at around 30, I was completely shocked by how modern it was and how many of the lines I hadn’t remembered, and how much of the story I had sort of completely sort of blocked out in my recollection of what the story was. And I felt that my memory of it, as a lot of people’s memory of it, which is the girlhood section, it’s when they’re all together and they’re young. And, actually, the book keeps going, and it’s really interesting and fascinating. And then it’s about, what do you do with all that ambition of your girlhood? What do you do with, when you were young, you could be brave and unafraid, because you’re in this house that allows you to be that way, and when you move out into the world, the world’s got no place for an ambitious woman? And Amy has a line, “The world is hard on ambitious girls.” I thought, this is — I — has anyone read this?

(LAUGHTER)

GERWIG: And I feel that often with certain books that get the sheen of a classic. You sometimes don’t investigate them again, because you think you know what it is. And when you do, you can’t believe how strange and wonderful it is. So, I was reading, and I was — and I kept underlining and I kept seeing things as being quite cinematic. And then I started researching Louisa May Alcott, who I had never really cared about as a girl, because, again, I lived just through the heroines of the book. I didn’t — I knew there was an author, but I didn’t actually think, I wonder who that woman was. I just accepted the book as it was.

MARTIN: And when you read that, you were, like, amazed. Like, what? This woman did what, when?

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: In the 19th century? Excuse me?

(CROSSTALK)

GERWIG: In the 19th century, some of the things she did, from — you know, she had her heroine — even though she didn’t — she never wanted Jo to get married and have children. She wanted Jo to be a spinster, but she was convinced by her publisher that that would not sell. So she had her get married and have children, but she, herself, she never got married. She never had children. She kept writing, and she kept her copyright of her book, which, in the 19th century, I — that’s insane. People hardly know to keep their copyright now. And she knew to keep her copyright, and that was the thing that economically saved her family. It enabled her to create a cottage industry of books, which she became fabulously wealthy off of. She sent her sister to Europe to study painting. She took care of her sister’s kids. I mean, she was this wonderful author woman and businesswoman.

MARTIN: And bad-ass.

(LAUGHTER)

GERWIG: She was a bad-ass. She was — she was bad-ass, and she was funny and she was mean, and all of her letters were — I mean, mean in the best way. But she had great one-liners. And I gave a lot of those one-liners and a lot of those moments to my character of Jo, because I felt like I wanted to collapse the space between Jo March and Louisa May Alcott.

MARTIN: There’s another clip I wanted to show. It’s where Jo is talking to Marmee, played by Laura Dern.

GERWIG: Yes.

MARTIN: And they’re talking about — I don’t know. What’s the right way to describe it? What it means to be a woman, how to figure out how to, what, fit into the world, once you realize that that’s what’s expected of you?

GERWIG: Right.

MARTIN: Does that sound right?

GERWIG: Right. Yes.

MARTIN: So, let’s play it, and then we can talk a little bit more.

GERWIG: Sure.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP, “LITTLE WOMEN”)

SAOIRSE RONAN, ACTRESS: When I get into passion, I get so savage, I could hurt anyone, and I’d enjoy it.

LAURA DERN, ACTRESS: You remind me of myself.

RONAN: But you’re never angry.

DERN: I’m angry nearly every day of my life.

RONAN: You are?

DERN: I’m not patient by nature. But with nearly 40 years of effort, I’m learning to not let it get the better of me.

RONAN: Well, I will do the same then.

DERN: I hope you will do a great deal better than me. There are some natures too noble to curb and too lofty to bend.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GERWIG: I love that scene. I love the two of them sitting together like that.

MARTIN: It’s just the fact that, you know, it is — there is that moment where, if you’re lucky, you get to know your mother as a person.

GERWIG: I know. And that line, “I’m angry almost every single day of my life,” that’s in the book, which I had never heard before. And I think it’s — so much of this book, to me, was hiding in plain sight. She says it. It’s right there. She’s angry. And I thought, that’s not how we collectively think of Marmee. Marmee’s not angry. You’re like, but what if she is? She’s angry. And then, when we were doing our research, and I involved the actors very deeply in this process, Laura Dern was actually reading all of these letters between Louisa and her mother, Abigail. And one of the things that Abigail wrote to Louisa about her anger, she said, “There are some natures that are too noble to curb and too lofty to bend.” And such is my Lou, who is Louisa. And so we took that and gave it to Marmee, because I felt like it was the real-life counterpart to what the discussion is here.

MARTIN: We are speaking at the beginning of the awards season. You know, you were nominated for an Oscar for “Lady Bird.” You were only the fifth woman to be nominated for an Oscar in the directing category. You weren’t nominated for this, even though the reviews already have been just rapturous. And I just wonder, does any part of it piss you off? Do you feel like you’re still fighting structures?

GERWIG: It’s hard because, in the thick of all this, of course, you — I’m personally disappointed that the movie didn’t receive more nominations. But I also think — I mean, I am thrilled Saoirse got nominated for her great work. I’m thrilled that Alexandre for his score got nominated, and I think that does speak to there’s enough love and appreciation of the film, but I — but I — but…

(CROSSTALK)

MARTIN: It’s not that you, as a woman, weren’t nominated. There was other fine work by women directors this year that was not acknowledged.

GERWIG: Yes. That’s the thing. That’s the thing. There was a tremendous amount of beautiful work. And I say that as a viewer, too, because when I go to the movie theater, which I go all the time, I’m excited by this work, and I know that there is great work. And, of course, I would love to see it acknowledged, but I’m also thrilled that the work exists, and I’m also thrilled that I get to make my next film, and they get to make their next films, and that we just get to keep making films. And in terms of being praised or being awarded, it’s lovely, but, to me, just that chance to keep making and to keep seeing their work, I think everything will catch up, I hope. I hope it will catch up, because it’s extraordinary work.

MARTIN: Greta Gerwig, thank you so much for talking with us.

GERWIG: Thank you. Thank you.

MARTIN: Thank you.

GERWIG: It was so wonderful.

About This Episode EXPAND

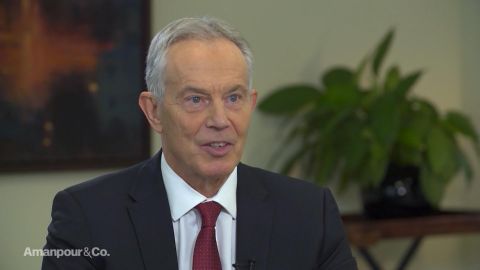

Former Prime Minister Tony Blair joins Christiane Amanpour to examine the deeply partisan politics rocking the U.K., screenwriter and director Greta Gerwig tells Michel Martin about her adaptation of “Little Women” and Michael Crick and Anne Applebaum discuss tensions between the U.K.’s Conservative Party and the British media.

LEARN MORE