Read Transcript EXPAND

AMANPOUR: Now, a story of achieving greatness in the face of adversity. Hakeem Oluseyi grew up in some of the roughest American neighborhoods. His father

was a drug dealer and his mother dropped out of high school at 16 after she became pregnant. His life seemed destined to follow in their footsteps, but

he’s now a world-renowned astrophysicist. His new memoir is called “A Quantum Life: My Unlikely Journey from the Street to the Stars.” And tells

Hari Sreenivasan how he beat the odds.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

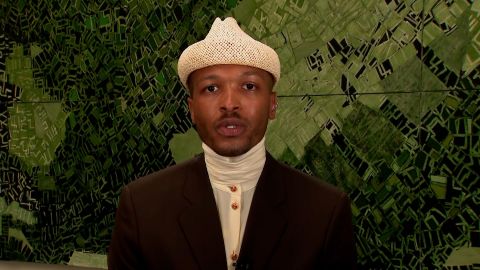

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, Thanks. Hakeem Oluseyi, thanks for joining us.

First, the name of the book, “A Quantum Life.” Now, I’m not a scientist but when I hear the world quantum, what I do know is that things can exist in

multiple states at the same time. What are the different states that your life exists in or existed in?

HAKEEM OLUSEYI, AUTHOR, “A QUANTUM LIFE”: Well first thank you so much for having me. You know, I call it basically the gangster side and the nerd

side. And so, I was schooled by my family in crime. And then I was a full participant. And at the same time, I was really interested in the natural

world and I wanted to be a scientist. And so, those two things were in conflict with each other.

SREENIVASAN: You talk about moving around a lot as a child in your early life. So, as you are moving around between Louisiana and Mississippi and

Los Angeles there were people, members of your family that were part of gangs in L.A. What did you see? What did you learn from that?

OLUSEYI: You know, it is more than just a gang. I got it from every part of the — you know, I got it from my family, I got it from my community, I

got it from the gangs. And my cousins, you know, they basically schooled, you know, me on how to survive. We’re about to go out. Here is how you need

to behave in these circumstances. If you hear this, do this. Right? They trained me.

But, you know, one thing I learned is how to ignore my pain, whether it was the pain of hunger or the pain of, you know, fighting. And so, when I

became an adult, you know, and after that, I went into the country where the, you know, work ethic is really hard core. By the time I’m an adult,

you know, I felt like, yes, maybe I am undereducated in comparison to my peers but I can outwork anybody. And so, that’s what I set about doing. And

a part of working hard is ignoring the pain. So, when others would stop, I’m going press on. I’m going to keep going.

So, this book is basically showing what I went through. Showing you what the communities are like. Showing you what people go through that are

different from the lives of most people. And even the way I got into being an astrophysicist, it was not, what do I want to be when I grow up, and

approach it. It was every day, how I do live indoors today, how do I eat today? That was my struggle. I did not get to a state of not just surviving

until I was deep into graduate school.

SREENIVASAN: I also want to ask a little about what you got from your dad, because he was for a large part of your life absent and in many ways, he

taught you a life that would have led you down a much worse path if you did nothing but follow it? But at the same time, throughout this arc of the

book, you are coming to terms with a son and a father.

OLUSEYI: Yes. Yes. Yes. That is the reality of it. My father was a complex human being. And, you know, so much of our actions are determined by

survival. My father was born in 1933 in rural Mississippi. He dropped out of school when he was nine years old. He left home at 13, went to the city,

New Orleans. And according to him he got a job parking cars for 25 cents a day. And then when he turned 18, he went away, the joined the army, went

away to the Korean War.

Now, our family, my father’s family, Mississippi always been entrepreneurial and, you know, he had to be self-sufficient because there

weren’t jobs to be had. So, they were bootleggers. And my dad took it to the next level. He started a growing operation in Mississippi and an import

operation in New Orleans and he was a wholesaler.

SREENIVASAN: Of marijuana?

OLUSEYI: Exactly. Marijuana. And I started with my dad’s business at the age of nine — excuse me, eight years old, when I was reunited with my

father, after being gone four years.

SREENIVASAN: What were you doing in your dad’s drug business as an eight- year-old?

OLUSEYI: Well, so you — first of all, when the product comes in, it has to be cleaned and packaged. The second thing is, when we were in

Mississippi, sometimes everyone would leave the house and I’d be left alone at the house and I’d be the person who conducted the sales.

SREENIVASAN: You wrote that early on you had an I.Q. test when you were a young boy and it was off the charts. It was 160, 162.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: There’s an aha moment that you describe when you are sitting in a stairwell reading basically an encyclopedic description of Einstein.

Tell me a little bit about that.

OLUSEYI: Yes. So, the year before at age nine, I read my first novel. It was the book “Roots” by Alex Haley. And I was amazed. I had already fallen

in love with reading, but I would read kids’ stuff, comics, books with pictures, things with humor in it. But now, I just read a book that was

serious. And what I found was that it was like a movie was playing in my mind. So, I’m like, I want to read as many adult books as possible.

And I looked around our home, I was left alone a lot, and there was sitting the set of encyclopedias. So, I thought, well, I’ll just read those A to Z.

And I got as far as letter E and that’s when encountered Albert Einstein and relativity. So, I’d always been attracted to the natural world, right?

First, it was Jacques Cousteau. So, when I was like five, six, if you asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I’d say an oceanographer, right? It

was also, Wild America.

But when I encountered Einstein, relativity had that weirdness that I love. I loved things that were really weird. And so, when you combine my love of

nature with love of the weird, you land right square in physics.

SREENIVASAN: Statistically speaking, you should not be having this conversation with me today. Given how deep you went into sort of the

criminal life and what the odds were of all of the things lining up for good and for bad to get you where you are.

OLUSEYI: Yes. Yes. That’s absolutely true. And I am very lucky in this sense that I got a lot of help. That was timely. There’s professors from a

nearby university who are like, oh, you guys should participate in science fairs. At our school, we had never heard of science fairs. And because I

had been studying relativity and recently thought myself the program in the program language basic, I thought, oh, I’ll program all the effects of

special relativity, and ended up winning first place in the state’s science fair.

Then my navy recruiter shows up. And he was like, yow, man, I’m going to find a way to get you into college. And he gets me into this program in the

navy where they take people from Rural America and inner cities and they give you a year of hardcore academic training and send you to college to

become an officer. And it was there that my mathematics was shored up. So, that when I got to college I could actually pass.

I didn’t think of going to college. When I got out in the navy, my friends were like, dude, what are you doing? Come to college. And I went. And when

I got to college, I had no idea what to do because, you know, there was no one in my family who had even graduated high school. So, you know, lot of

people helped me out along my path to the point where it almost seems like it was destiny. But I had to fight and work super hard every step of the

way.

SREENIVASAN: And you end up going to a historically black college.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: A small one that probably nobody at your graduate program had ever heard of.

OLUSEYI: When I got out of the navy, I was aimless. It was 1986 and I was looking for a job. And some of my friends told me, man, you need to come to

college. And I was like, I don’t know. And they were like, come up Tougaloo where we are. You will love it. I showed up at campus without even

applying. So, I didn’t know how the process worked. But they knew how to deal with students like me and they got me enrolled.

And so, you know, I was kind of aimless when I first started. Things went downhill for me very quickly. And I dropped out. And I got this job as a

janitor. And the reason why I did that is simply because I wanted to live. As we say in Mississippi, I found myself looking down the stupid end of too

many gun barrels.

And so, I got this job as a janitor. And I thought that, you know, I could work my way up in the hotel, someday be a hotel manager. And what happened

is, when the bellhop got fired, I thought this was my big break because, you know, as a bellhop, I could maybe get a hundred dollars in a day,

right? Man, I was not bellhop material. I wasn’t front door material. And I thought to myself, I can’t go from janitor to bellhop? I’m going back to

college.

SREENIVASAN: So, you get through your undergraduate work, and then you qualify to be among the elite in the country as a grad student at Stanford.

What happens there?

OLUSEYI: When I get to Stanford, it is completely new environment. I’m introduced to classism for the first time. You know, I grew up in the deep

south and the issue was always racism. And I remember chatting with my mother on the phone and she made some mention of race. And I said to her,

mom, being white ain’t even good enough here, because, you know, it was really about class. You know, I didn’t see anybody around me with a deep

southern accent, for example, like I had back home.

And when — you know, I — when we got there, us physics students were given a list of everyone else who was a first-year physics graduate

student. And it read like a list of the top universities in the world. All the top U.S. universities in. And then Tougaloo College. And so, the

students, at first, they were like, oh, this guy must be a genius. But, you know, I was still vastly undereducated in comparison to my peers.

So, there is a mixture. There’s people — most people are just concerned with themselves and then you meet some people that are really good people

and you meet some people that are hostile to you. And that’s what I happened to meet. And the hostile people happened to be in the physics

department. And some of them were my professors.

The beginning of my first four years, starting my second year, third year, fourth year, it was like a ritual that they would attempt to undermine my

progress. The next year, they suggested to me that I should leave the program. And you know — explicitly. And I don’t and go on to have a very

successful research career.

SREENIVASAN: You were at Stanford, in grad school, literally doing rocket science. And by night, at one point, you are out trying to score crack.

OLUSEYI: Yes. You know, I never — once I came into this world and I left my past behind me, I never mentioned it again. And so, this is the first

time in this book that I’m revealing this to the world. I hate hearing that word associated with me, but, you know, it’s the reality. I had three bouts

with that in 1988, 1990 and 1992.

In 1992, I was 25 years old. And that is exactly what happened. I got to Stanford University, and I didn’t realize how much I was in trouble with

addiction. If you haven’t been through it, it is hard to imagine. It is so insidious. It’s such — you know, people say it calls to you and it comes

to you in your dreams. It is all true. It really is. And so, I found myself in trouble. And I found myself in East Palo Alto. And the funny thing is,

if you have ever seen the movie, “Dangerous Minds,” I was actually tutoring mathematics at that school at the time.

So, while I was — whereas I’m, you know, trying to uplift people from my background, I’m destroying myself. But, you know, that was a part of my

growth. Because going through what I went through as a youth, I did find — I did feel worthless, you know, and I did feel like I wanted to destroy

myself. But, you know, I use the example of the person who feels like they want to commit suicide and jump off a bridge. But once they get in the

water, they start to swim because they really don’t want to die. And that is where I was.

You know, I was on a self-destructive bent, you know, because of all I — the abuse I had suffered, all I had internalized. But really, I wanted to

live. I didn’t want to die. But, you know, what I had learned was when these tough times hit, you know, maybe it is me. Maybe I need to destroy

myself. And so, I hit rock bottom and I’m like, you know, I have to change this somehow.

SREENIVASAN: You were not only using, but you were also dealing these drugs when you were at Tougaloo.

OLUSEYI: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: And I wonder if this is the first time you’re revealing some of these things in the book what your peers or colleagues or others have

been thinking about.

OLUSEYI: Yes. I wonder what they’re going to think also. But you know what, I realize that it’s not about me at this point. The reason why I

wrote the book, as I — I started going out speaking and inspiring others to careers in STEM when I was still a graduate student. And people get it

when I am the person who is delivering it to them, right? They realize it is cool. They realize they can understand it. They realize they can do it.

And so, people — you know, I’ve created a generation of scholars from different communities. So, I realized that my story has such a power to

uplift people, that, you know, my — I’m more — I’d be ashamed at myself if I didn’t tell it. You know, and that’s the toughest scrutiny I have to

live with, is dealing with what I think of myself, and I see it as responsibility.

SREENIVASAN: You find a mentor here. What did that mean to you? And what did he do for you?

OLUSEYI: Yes. Art Walker was one of the first three African Americans to go into astrophysics in America. He got his PhD in the 1960s. And he was

one of two black faculty in all of the six schools of science and mathematics at Stanford University.

And so, when I got to Stanford, I wasn’t going in there with the mindset, oh, I’m going to go and work with the black professor. I was looking for

experimental astrophysics. And it turned out that the only person that did experimental astrophysics was Art Walker at the school at the time.

And so, in the physics department, there was Phil Schairer (ph) in applied physics. So, I thought that I’d work with Art. And Art taught me not only

how to be a scholar, he taught me how to be a gentleman. He gave me a different example of being and he also a different example how to behave

professionally and how to handle difficulties when they arise in a professional world. And that’s been very important. Because, you know, the

workplace is fraught, and I’ve survived wrongdoing by others because of what Art taught me.

SREENIVASAN: Well, in non-science speak, what did you and Art, what did you study together? What did you discover together?

OLUSEYI: If you look at the structures on the sun, there are these plasma loops, there are these plumes. We were discovering how this atmosphere,

even though the surface of the sun is just under 6,000 degrees kelvin, how does it have this extended atmosphere over million degrees indefinitely,

what we call the solar corona? And if you think about how strong gravity is at the surface of the sun, why is this atmosphere streaming out into space

to form the solar wind? There must be some powerful force here. So, we made advances in understanding how the atmosphere is heated and how the solar

wind is accelerated.

SREENIVASAN: Do you think that Art and yourself were questioned by the scientific and academic community differently because you were black

physicists?

OLUSEYI: Well, it is not something that we have to ponder. Because, you know, people are sometimes very explicit about this. It was — you know, I

heard faculty say, oh, Art Walker, he doesn’t know anything. Which was ridiculous. If you knew Art, Art — like if I ever met a genius, and I’ve

many, but Art was on another level. And he was super square too, right? So, that even makes you more genius.

And so, I thought to myself, if he’s getting it, I don’t stand a chance. I feel like this. You know, you are born into a world. And I have to survive.

And I’m looking to thrive. So, if that’s the conditions that I’m in, that I have to fight and survive and thrive under, then that is the conditions

that I’m in. So, that is exactly what I’m doing. And I’m training others to be successful as well.

SREENIVASAN: So, tell me in kind of basic terms, what are you doing today? What are you studying? What are you exploring?

OLUSEYI: I’ve been doing recently what is known as galactic archaeology, that numbering of the stars, thing allows you to untangle the structures

that made the Milky Way Galaxy. And so, when you understand how galaxies form, you can understand in part how the universe formed.

And the other thing is, when we look at the surface of the sun and how the sun accelerates particles to form the solar wind, one of my graduate

students realized, hey, we can make a machine that does the same thing. And so, we created a new ion propulsion technology. And, of course, at all

times, I’m thinking about very fundamental problems that have to do with the origin and evolution of the universe and the nature of our universe.

SREENIVASAN: Hakeem Oluseyi, thanks so much for joining us.

OLUSEYI: Thank you for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

Iran has elected its most hardline leader since the Islamic revolution 43 years ago.

LEARN MORE