Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, an online playbook seems to be emerging around some of the important, but difficult political conversations these days. Someone says something deemed offensive or troubling to someone else, and social media goes into a frenzy and that person is effectively canceled. Well, an open letter recently published in “Harper’s” magazine claims that this poses a threat to free speech. It was signed by 153 prominent writers, academics and artists, including the likes of Gloria Steinem and Salman Rushdie. It’s become quite controversial. Here is our Walter Isaacson speaking with the co-author of that letter, Thomas Chatterton Williams, who’s a contributing writer for “The New York Times” magazine and a columnist at “Harper’s.” And they discuss our current age of moral reckoning.

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And welcome to the show, Thomas Chatterton Williams.

THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS, COLUMNIST: Thanks for having me.

ISAACSON: Explain to me this incredibly famous now letter. What was the point of it? What caused you to write it?

WILLIAMS: The letter comes out of a conversation that I have been having with four of the other writers who drafted the original text with me about a kind of atmosphere of censoriousness and impermissiveness that has been affecting all of our culture and media institutions for some time now. It doesn’t come out of one event in particular, but a kind of mood has set in, a mood that feels as though we are less and less free to speak in ways that deviate from increasingly rigid orthodoxies. We are less and less free to experiment and perhaps even sometimes make a mistake in a landscape rapidly evolving norms.

ISAACSON: Can you summarize for us exactly what the thesis was and what arguments you were making?

WILLIAMS: Yes. Well, we were saying that you cannot have a just environment without that environment being free. So freedom and justice are inextricably linked. We stand with the protests against police brutality, and we stand with the larger movement that has been starting a conversation about making our workplaces more inclusive. We’re for maximum inclusiveness and tolerance and the freedom for people to have diverging views on good faith. We see — we uphold those values as fundamentally liberal values. And we see a creeping extremism on the left and the right that makes the kind of atmospheric censoriousness, and that is in opposition to these liberal values.

ISAACSON: What has surprised you about the amazing reaction to that letter?

WILLIAMS: I mean, I have been surprised by the sustained interest in this topic, and I have been heartened by it. We’re approaching two weeks of constant conversation. Yesterday, 100 Spanish-speaking intellectuals, including the Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa, signed their own open letter in support of our manifesto and saying that this was an issue that transcended national boundaries. I think we really hit on something that resonates with people that is not made up or just the kind of fear elite losing some positions at “The New York Times.” I think we really hit on something that is real.

ISAACSON: Sometimes, it seems to me that these discussions are true, and the points you make are true, but that they can be overblown a bit. We see a few really bad examples of censorious culture. But then we see recycled the same handful of incidents. How bad do you really think this problem is?

WILLIAMS: Well, here’s the thing. You have a few incidents that people tend to talk about over and over again. And then you have some cases that never make it into the public consciousness. But it just takes a few cases, actually, to have an enormous effect. So, the way that — the kind of perniciousness of cancel culture is that it thrives on public humiliation and shaming. And so all you have to do is take somebody and make a significant enough example out of them, that you have an enormous effect on all of the onlookers. And so that’s what we’re really talking about. We’re not just talking about high-profile cases. And we’re not just saying that the people signing this letter, many of whom are very successful — and, frankly, that success can’t be taken away from them at this point. But they’re saying that this larger culture matters because of all the people you don’t care about who then like make themselves smaller in order to not be publicly humiliated. And there are some cases that I can talk about that are pretty chilling, in and of themselves, regardless of the onlooker effect.

ISAACSON: Well, give us some of those cases.

WILLIAMS: Absolutely. Just recently, Gary Garrels, a curator at a museum in San Francisco, was forced to resign for saying simply that he would continue, even — in his efforts to diversify the museum’s art collection, he would continue to also buy white artists. This sparked a revolt and he was forced to resign and was deemed a white supremacist. You have the case of David Shor, which now has become quite well known, the young data analyst at Civis Analytics, who somebody retweeted research by Omar Wasow, a black academic at Princeton University. And I hate to even put his credentials in racial terms, but you kind of have to point out that he’s a black academic. And David Shor retweeted research of his showing that, in election years, when there’s nonviolent and violent protests, the violent protests can have an adverse effect on democratic politics — on the election of Democratic candidates. And he used Richard Nixon as a case study. David Shor retweeted this research without adding commentary and was quickly kicked out of a listserv, a progressive listserv (INAUDIBLE) and then fired.

ISAACSON: Well, I’m old enough to remember the late ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s, when — people talking about political correctness, and then writing about the thought police. And every decade, we have some pushback on this. Has it actually really gotten any worse?

WILLIAMS: You know what I think is really different, and we’re only starting to understand how important this change has been, is the technological shift that’s happened in the social media era. So I really do believe that enough of a quantitative change becomes a qualitative difference. So people have always been held accountable or fired or even blackballed and ostracized. What is new now is that we have these rapidly shifting norms. Somebody trips over a new norm that isn’t even yet spelled out in stone, that is not part of the employment contract or what have you, is not even necessarily a fully accepted social norm. They’re called out online. And there becomes a mass kind of reaction to this, with many strangers involved and some high-profile voices, and it whips up a fervor that targets not just this person, but this person’s employer. And then that gets into the person’s H.R. department, and very swift kind of reactions are made where the person is canceled, effectively, so that the institution or employer can be done with it. But even worse than that, a kind of stigma attaches to the person that has been targeted, and they become outside of the sphere of employability elsewhere, or they retract their novel, or they resign from a board, and they don’t go on another board. And these might seem like, well, those are nice problems to have. But this trickles down. I have an inbox full of e-mails from young associate professors, editorial assistants, people working in law firms who tell me that they are afraid to say what they actually think. They have never fully said what they think because they’re so afraid of the repercussions that could come their way.

ISAACSON: But aren’t there a lot of types of views and comments that deserve to be stigmatized? Isn’t that how we set the bounds of civil discourse?

WILLIAMS: Absolutely. And I think that when you talk about someone like the lead writer on Tucker Carlson’s widely viewed show on FOX who lost their job recently when it was discovered that they were operating under an alter ego that was saying pretty awful, racist stuff, I’m sure that that violates some aspect of their employment contract. That’s a known line that was crossed. The problem with cancel culture is that you’re often getting caught up in things that haven’t yet been cemented in the public square as black-and-white violations. They’re evolving norms. And part of your punishment is to make the norm stick. And so that’s kind of scary. And you don’t really have a way of defending yourself when you don’t know that you’re even violating something.

ISAACSON: What about J.K. Rowling? She’s a signer of the latter. She has controversial opinions on transgender rights. Did that distract from this?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that if she has views that are controversial and are worthy of being refuted, then the best way to do this is not to say that they’re forbidden and cannot be aired, that they have to be hidden from adults who can be convinced and prevailed — their reason can be prevailed upon. But those arguments should be brought out and should be refuted openly. And I think that she’s — I don’t know her, but I think that she would welcome that kind of debate as well. She’s somebody who has a long track record of standing for liberal values. And so I thought that the strength of the letter was that a wide variety of people can sign it, and that those values will be worthy, independent of the signatories. And I want to say that I come from a kind of viewpoint that Bayard Rustin articulated so well, which was that, if a bigot says the sun is shining, I will still say the sun is shining because my loyalty is to the truth. Now, I’m not saying that anybody on the list was a bigot. We wouldn’t have invited anybody to sign if we believed that they were bigots, but I also want to detach — I want to refute this notion that the truth is dependent upon who is at any given time articulating it.

ISAACSON: You say you wouldn’t allow anybody to sign if they were bigots, and that maybe, when we have platforms, we should draw the line at bigots. How do you draw that line, though?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that, in our employment — in our terms of employment, we have regulations that work for what is bigoted. And there are things that you cannot say and do at work that are very clear, and people get fired. I think a lot of us, we can parse these things, but a lot of us understand what certifiable bigotry is. On the edges, where we’re redefining and perhaps in a way that is very necessary, we’re redefining what exactly we believe and want to believe bigotry is, then I think we have to have — again, we have to have more generosity in allowing people to be convinced and arguments to be made and people to be persuaded before we get to the gotcha phase and the public humiliation and punishment phase.

ISAACSON: We have seen a lot of incidents recently in which there’s both issues of race and then the very censorious or huge Twitter backlash culture. One of them was about the birdwatcher, the African-American men birdwatching in Central Park, and the white woman who then confronted him. And she lost her job. She was attacked. Help unpack that for me. Was that overreaction or was that something that was useful?

WILLIAMS: They even took her dog away from her. I mean, she suffered a complete evisceration of her public persona in the world. And she — this woman, Amy Cooper, obviously behaved in ways that I find reprehensible. But I seem to find myself siding more with Chris Cooper himself, who said that he felt that the reaction was — it was just — it was too much. What happened to her was out of all proportion with what she had actually done. No one was actually physically harmed. But this woman died a public death, metaphorically speaking. She was expelled from the realm of acceptable human beings. And I can’t kind of overstate how terrifying that is and what that does to people and how that constricts the atmosphere of public discourse and the idea that even people can be rehabilitated. I want to be very clear that I don’t agree with the way that she behaved in the park whatsoever. And it does happen to a longer history of people calling police to punish and disciplining, sometimes physically break black people for simply doing things that they don’t want to be done, for simply being in the space with them. So it taps into a pretty ugly history. But I don’t think that we want to live in a world where we all can become Amy Cooper.

ISAACSON: Would you say it constricted behavior like that? And you say that thousands of times. I mean, I see it every day, where a white person will use a particular type of power and hurt or humiliate or do something that is basically racist. Don’t we want to restrict that? And isn’t what happened to Amy Cooper just a warning signal to the rest of us to be more careful?

WILLIAMS: It’s certainly a warning signal. I think that she should have — she should be held accountable for that. She should have ramifications for that. Where I do keep struggling to understand our impulses is, why do we always have to take away someone’s livelihood for so many of these transgressions? This was not something that she did at work. This had nothing to do with her performance at work. This is something that she deserved to be called out on, and we need to have the behavior stop. But we seem to always go to the superlative of the disciplinary action, which is that you must not be able to have a livelihood. That’s chilling. So, one of the things I think about a lot in this discussion with cancellation is a lot of the pushback has been, well, black people and marginalized people have always been getting canceled. So all that’s new is that white people are getting canceled, too, now. That may be the case. I certainly am very sensitive to that argument. And I have seen the way that racism has worked throughout my father’s professional life. I’m sensitive to that. But I don’t think that the world that I want to create is one in which we are all rendered as vulnerable as the most vulnerable people used to be. I’d much rather see a world where we can all be made as secure and as able to feel free to have a generous kind of response to our actions as white people have traditionally been able to feel themselves to be.

ISAACSON: So, what should happen to people who truly transgress the bounds of racism, anti-Semitism?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think what has to happen is that we have to have a real understanding of what racism is. These definitions are rapidly shifting now. So, in any moment when things – – when definitions are rapidly shifting, we have to give people a chance to catch up. We have only just gotten into a conversation where people are widely accepting an idea of racism that’s systemic in nature, and not about the hatred that you have in your heart, as George Bush would have said. That’s all to the good. We should have a more expansive understanding of all the ways in which inequality operates. But we also have to give people who have spent 50, 60, 70 years of their time on this Earth thinking about reality in one way a chance to adapt to a new system of reality before we immediately hang them out to dry. So I think we have to understand what racism is. And if we’re going to go to an extreme, like what Ibram X. Kendi or what Robin DiAngelo says it is, I think we have to have a chance for some counterargument. And that’s where I try to push back.

ISAACSON: I’m going to ask a very philosophical question. I know why I’m in favor of free speech, and you probably do know why you’re in favor. But explain to me, why is free speech a good thing?

WILLIAMS: Oh, that is a very philosophical question, because we don’t know what all the right answers are yet. We don’t know what the better tomorrow will be until we try to articulate a vision of what our better tomorrow could be. And that takes hearing from as many perspectives as we can possibly cobble together. And so, the more you limit what can be said before it’s even uttered, the more you limit how many, like, stabs at getting us towards this better tomorrow can be heard and can be tested out and can be aired out and exposed to the kind of debate that lets us know what’s worth keeping and what’s worth rejecting, I think we have to always have a kind of humility and modesty. And that modesty makes us want more speech. I think that marginalized people are most able to flourish in places and societies and spaces where culture is free and experimentation is encouraged. I think that people shrivel up and marginalized people always fare worse in highly restricted spaces. One of the responses I got that meant the most to me was from a man who identified as African-American on Twitter, had a very small account with about 200 followers. And he said, I’m not famous enough that anyone will ever ask me to sign an open letter, but no one’s ever explained to me how, as a black man in America, my life will be made better with less ability to speak freely. No one’s ever explained it to me. So thank you for doing this. And I took that very seriously and to heart.

ISAACSON: Thomas Chatterton Williams, hey, thanks for being with us.

WILLIAMS: Thank you so much for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

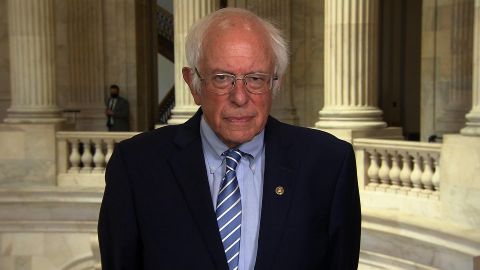

Sen. Bernie Sanders explains why he thinks Joe Biden could be the most progressive president since Franklin D. Roosevelt. Persepolis creator Marjane Satrapi discusses her new film “Radioactive,” based on the life of Nobel Laureate Marie Curie. Author Thomas Chatterton Williams joins Walter Isaacson to discuss “cancel culture” and his book “Self-Portrait in Black and White,”

LEARN MORE