Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Tonight, the House select committee investigating the January 6 insurrection is holding the first of a series of televised hearings. Nicole Hemmer is an author and historian specializing in the history of conservative media in the United States. And she joins Hari Sreenivasan to discuss the significance of this moment and what it means for U.S. democracy.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN, CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Nicole Hemmer, thanks so much for joining us. So what is at stake at these hearings?

NICOLE HEMMER, AUTHOR, “MESSENGERS OF THE RIGHT”: I think the most important thing that has to happen is that the members of Congress have to connect the mob violence on January 6 to these broader attacks on the democratic process, both the conversations that were had happening before the election that were spreading lies and conspiracies about what had happened in the 2020 presidential election, but also the efforts that have been happening since at statehouses, with secretary of state’s offices, in order to make it possible to overturn future elections. So they really need to make that connection between the scary scenes from January 6 and the ongoing threats to elections.

SREENIVASAN: As a historian, why is it important to set the record straight, to get the public the information about January 6? And do you think the committee is going to be able to accomplish this?

HEMMER: So it is absolutely key that we have a clear historical record of what happened that day that isn’t just the scenes that we saw on media, that isn’t just political spin that happened after, but that we understand who were the people who were responsible, what kind of planning went into this, how much of it was spontaneous, how much of a connection was there between the White House members of Congress and people who were involved in the insurrection? Even if that doesn’t change politics in the next year or the next five years, it’s important for us to know what happened, so that there is a time when we can begin to set the record straight. We have had periods in the past in the United States, whole decades, where, say, the Civil War was seen as not about slavery, or that the South was ill-treated by the Reconstruction period that happened after, and that it was actually terrible that black people had the right to vote and the right to serve in government. That was a shared belief among many, many Americans because a false narrative was put forward about what the war was about and what Reconstruction was like. Historians can now go back and tell that fuller story. They can explain and explore what happened in those years and offer Americans today a fuller understanding of their past. And I realized that’s a very long-view answer. But Reconstruction happened 150 years ago. Hopefully, we won’t have to wait that long for there to be a more robust and a shared understanding of what happened during the insurrection and why it mattered, why it was so important. But we have to have that record preserved, so that we can tell that story and so that we can make sense of what the long-term attacks on democracy, of which January 6 was only a part, how that unfolded, what it looked like, and how Americans responded.

SREENIVASAN: Perhaps since Watergate, we have all become almost used to or expect some sort of a bombshell when it comes to political scandals and congressional hearings. And if we don’t have that, what should people still take away?

HEMMER: That’s right. And we should talk about that smoking gun idea. I mean, people’s understanding of political scandal and political wrongdoing were very much set by the Watergate hearings, and they had those secret recordings and that smoking gun tape, and that really has, for the past half-a-century, set people’s expectations for what these kinds of hearings can do. And so the folks on the committee are going to have to be a little savvy in how they present this information, both weaving in all that we already know, all that we already saw on January 6 with text messages that were happening behind the scenes and secret conversations between the president and, say, the secretary of state in Georgia, and have those, if not bombshell moments, than moments that say, hey, we’re pulling the curtain back, and we’re going to show you what was happening behind the scenes. And they need to do that not because it’s the most important evidence, but because it’s the most impactful evidence, because that’s what folks are attuned to when they’re watching.

SREENIVASAN: When they’re watching leads me to this notion of the existing divided country and who has an interest in watching something like this. And, right now, FOX News, which serves an enormous audience, has chosen not to air these hearings, and to continue on with their prime-time programming. There seems to be a large population of Republicans who just want to move on, and that this is not going to be any new information to them.

HEMMER: That’s right. And that’s a political argument. I mean, it’s not just about wanting to move on. It’s about the politics of January 6 and a real effort that’s been taking place, not just around the January 6 hearings, but over the past year-and-a-half, to say what happened on January 6 was just not that big a deal. We shouldn’t be returning to it again and again. It’s not important. It’s not what Americans are focused on. And that argument is a political argument. It’s about distancing the party from those events, precisely because you had a Republican president who was at the forefront of the fight to overturn the election. You have Republican lawmakers who are voting to overturn the election and you had Donald Trump supporters who were responsible for breaching and attacking the capitol. And so, it was this partisan event. So, understandably, there are partisan politics in the kinds of narratives that people are telling in the aftermath.

SREENIVASAN: In the moments, the day of, the day after, we saw very different announcements and pronouncements from the actual capital on what was tolerable, what was not going to stand, and then, we saw a party get back in line with the president.

HEMMER: We did, and it is telling about how dramatic and how frightening January 6th actually was, and what a big deal it was, that in the midst of the attack on the capitol, there were people, regardless of what their political affiliations were, whatever their allegiances to President Donald Trump at the time were — they were terrified. They were scared for their lives, and they understood that something historic and historically awful what’s happening. And that gets overwritten by a set of political concerns. It gets overwritten, not only in defense of President Trump, but an understanding that there was a significant portion of the Republican base, of the Trump base, that supported what happened on January 6th and did not want it to be treated as the political crime that it was and the political violence it was. And you see that as soon as that evening, when you still have 147 Republican legislators voting to overturn the election. So, that immediate fear, that immediate sense of threat gets overwritten by politics pretty quickly.

SREENIVASAN: You know, what was disturbing most recently was the Department of Homeland Security issued another warning, and I want to quote a little bit from it, “In the coming months, we expect the threat environment to become more dynamic as several high-profile events could be exploited to justify acts of violence against a range of possible targets. These targets could include public gatherings, faith-based institutions, schools, racial and religious minorities, government facilities and personnel, U.S. critical infrastructure, the media, and perceived ideological opponents.” I mean, you know, unfortunately, the country has become used to mass shootings and violence, and in this climate, while we have these hearings going on, we also have a person who turned himself in outside of Justice Kavanaugh’s house, who said that he wanted to kill him, and that he was armed to do so. The ripple effects of January 6th, I think, it seems that they play into a larger direction towards violence that the country is heading in.

HEMMER: That’s absolutely right. That these spectacles of mass violence, which didn’t begin on January 6th. The January 6th was, in some ways, as much inspired by what happened in Charlottesville in 2017. That we have had these spectacles of mass violence at the core of U.S. politics, particularly in the last 40 years since the Oklahoma City bombing, but these spectacles of mass violence we get other acts of mass violence. And they — we get them especially when they are greeted with some level of political indifference. If there aren’t any consequences for this kind of violence, if there’s a political embrace of acts of mass violence, then, it’s going to happen more frequently. Of course, it is also abetted by weapons of war that saturate U.S. society. So, there are a lot of reasons why we’re seeing more and more of this, but it’s not just that, right? Because January 6th was not people carrying AR-15s. There are other ways to carry out these kinds of violent spectacles. And again, we saw that, too, in Charlottesville, right? It didn’t take long guns, although there were lots of those there. There are other ways to commit these acts of violence. But when a society is saturated in them, it generates more of it because people see it, and they emulate it.

SREENIVASAN: You know, when you mentioned the Oklahoma City bombing, the response in the country to not just the perpetrators, but the leaders that were there at the time, who might have shared some of these beliefs, and really, the lack of accountability, I mean, they were not all voted out. I mean, did that set a pattern for how the Republican Party might have changed over time?

HEMMER: I believe so. I mean, there were people in Congress at the time who had very close ties to militias and to white power groups. And during the Oklahoma City bombing, they, of course, said, you know, we denounced the bombing. It was a horrific act. At the same time, these militias have real grievances and the U.S. government has a real culpability here. And those members of Congress didn’t pay a price. They were re-elected to office. They won their primaries. They were appointed to high-profile committees, and of course, there were hearings on militias that happened immediately after the Oklahoma City bombing, many of which kind of soft peddled the violent rhetoric and ideology behind this militias. And so, because there was no political price, because there was an attempt to paper over the violent ideologies at the heart of some these movements, people learned that you don’t pay a price for extremism. In fact, it can give you a bigger platform.

SREENIVASAN: One of the things that you study at length is the role of conservative media. And I wonder how — I mean, in the last six to 10 years, at the very least, it seems like it is a part of not just how people get information, but an active part of the campaign of conservatives or Republicans in America.

HEMMER: That’s right. And that’s been the case for a very long time, that conservative media has increasingly become part of the communications arm of the Republican Party. Not just communicating what party elites wants you to know, but serving as a mediator between the party’s base and politician and officeholders. And it has grown ever more powerful in the past 10 to 15 years, not only in shaping conservative ideas and shaping conservative politics, but helping to launder mainstream, the extremism, that comes from the further fringes of the party, to make something like replacement theory just part of Republican ideology, or to take something like the events on January 6th and say, look, not only was this not a terrible attack on the country by Trump supporters, but the people who were arrested for the events of January 6th are political prisoners. And this was, in fact, carried out by agent’s provocateur in the deep state, like those conspiracies become mainstreamed and legitimize when they appear on something like Fox News or in sort of the more mainstream and elite parts of conservative media.

SREENIVASAN: Explain how that kind of laundering happens. I mean how does something get from a small corner of the internet and a conspiracy theory out to millions of people on primetime television?

HEMMER: So, it happens in different ways. So, sometimes, you’ll have a conspiracy theory that catches on on social media, something like Facebook or Twitter. And of course, you have people who are creating these shows like “Tucker Carlsen Show,” who are paying attention to what’s trending on social media. And so, it can kind of get in that way. But also, we have a very more — a much more direct version of that with “The Tucker Carlson’s Show,” because he had a writer like Neff who spent a lot of time on far- right sites, posting antisemitic and white nationalist content and bragging about getting that content on air. So, he was the head writer for “The Tucker Carlson Show” and was able to get those ideas in more coded and mainstreamed ways on to Carlson’s show. So, that was another way that it filters in. You have true believers in these fringe ideas who are helping to create this media content, then you get this cleaned up version of it on primetime television.

SREENIVASAN: You know, it’s used to be that we had media played a crucial role in helping us see maybe a shared reality, that people were old enough to watch the moon landing, it was a universal moment we could all agree was a fact. And, of course, you look at YouTube now, there are conspiracies that say the moon landing didn’t happen. But at the time that we had a trust and a faith in the institution that they were bringing us reality at the same time as the same place. And now, what you’re describing is a way for parallel realities to coexist.

HEMMER: That’s right. And that’s kind of where we are. And the January 6th hearing are an excellent example of what that information gap or that reality gap looks like, where two people are talking about the same events, and they have no shared understanding of those events Now, you know, you talk about something like the moon landing and that shared media culture, that is certainly the case. Not everyone was able to participate in that shared culture, not everyone was represented in it, but also, you know, it is that same media, those same television networks that were telling people that the Vietnam War was going great. And there is a reason people lost faith in institutions, and it wasn’t just there was an outside attack on those institutions. Those institutions lost credibility because they weren’t being credible. And so, there is a responsibility across the culture, from journalists, from politicians, from ordinary people to rebuild those institutions and rebuilt trust and faith in those institutions. Right now, there are a lot of political reasons why that’s not happening. And until those political incentives change, we are going to continue to have this fractured and bifurcated culture.

SREENIVASAN: So, how do we prevent another January 6th from happening if we can’t agree on what’s happened on January 6th, and why it happened?

HEMMER: I don’t think that you can. I mean, I don’t want to be a pessimist on this, but even something as straightforward as security protocols at the capitol are something that we weren’t able to agree on almost immediately after January 6th happened. There were protest over metal detectors on the floor of Congress. There were debates and fights over funding capital police, or bringing more capital police to the capital to defend it. And so, if you can’t even agree on those security concerns, I think it is very difficult to create a robust set of rules or shared ideas or any sort of policy mechanism that would prevent another January 6th from happening. It just — it doesn’t seem to me that we are less likely to have another January 6th a year and a half out from it based on everything that’s happed in politics since.

SREENIVASAN: Nicole Hemmer, thanks so much for joining us.

HEMMER: Thanks so much for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

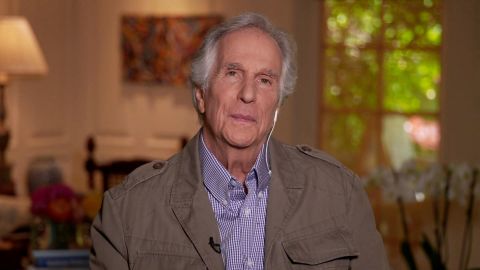

The Russia-Ukraine War puts pressure on some of the newer democratic countries in the region — notably Montenegro. A first-hand look at Rwanda’s preparations for the Ukrainian refugees’ arrival. “Happy Days” star Henry Winkler is still winning awards for his inimitable work — most recently in the pitch-dark HBO comedy “Barry.” Nicole Hemmer discusses the significance of the Jan. 6 hearings.

LEARN MORE