Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, our next guest went from jail teenager to award-winning poet. Reginald Dwayne Betts committed a carjacking in Virginia at the age of 16, and he ended up spending over eight years in adult prison. Since his release, he’s turned his life around. He’s earned a degree from the Yale Law School and he’s authored several critically acclaimed books. His book “Felon” tells the story of the effects of incarceration on identity. And he told our Michel Martin, about the power of the written word and the importance of forgiveness.

MICHEL MARTIN, AMERICAN JOURNALIST: There’s so much literature around prison life and what leads to prison. But so much of it is either people who were falsely accused, or people who never had a chance. And the reality of it is, in your case, you’re neither, I mean, you were an honor student, and you decided to carjack somebody along with a group of friends. Can you tell us why?

BETTS: That’s the million dollar question. And I wish I had an answer. I think one of the things that I said early on, actually, when I got locked up, I remember having to call my mom and tell her and that was the first time that it struck me that I had no reason to be where I was. The person I robbed, I might have gotten $10.00, but I wasn’t even thinking about money. We weren’t rich, but I didn’t need money. I wasn’t really into joyriding, I had never really done it before. I might have driven a call once before that night, and I only held a gun one time, and that was that time right there. So there was no rational reason for me to do it. And I spent, you know, really the next 23 years up until this moment, trying to find a better answer for me doing it than what I fell upon, which is simply, it was just in the realm of possibility. And there was so many reasons for it to be in the realm of possibility, whether it was just a community that I lived in, whether it was just the friends that I chose, whether it was just our willingness to not believe that our life was worth more and spending a huge chunk of it in prison. But in that moment, I just — I just didn’t believe that my life was more valuable than the risk that I knew that I was taking.

MARTIN: The anniversary of the incident is right around now. Do you think about it?

BETTS: I think about it way too much. Because, you know, we all say we have moments that profoundly change our life. And we all, I think, accumulate those moments, but that’s the saddest day that changed everything. I’m a writer, I decided to be a writer because I was incarcerated. I write about being incarcerated. I think about who I am as a father, who I am as a parent, who I am as a member in a community and all of that reflects on these experience that I’ve had. I’m a lawyer, and my first introduction to the law was reading the Bill of Rights and my right to a jury of my peers as a 16-year-old and contemplating the fact that going to prison at 16 meant that there’s no way I would ever have a jury of my peers. And so, you know, so much of my life is sort of just invested in that moment that I’m constantly thinking about it. And you know, December 7th, December 8th comes back around, and it makes me pause, you know, and both reflect on how I can appreciate my successes, but how it’s hard to reconcile it. You know, when you have so many greatest successes borne of your biggest failure, it is hard to reconcile the two sides.

MARTIN: Do you remember when you got up that morning? Like what was on your mind? Were you bored?

BETTS: No, I was with friends and I was with people I didn’t even know. I mean, that’s the thing. You know, you told a story, I was with one person that I knew well, and three people that I didn’t know well at all. And literally, you know, it sounds like a lie. What do you mean, you were with three people that you didn’t know and one person that you did know, and then within a span of 45 minutes, you all went from laughing and joking and smoking a blunt to contemplating and then carrying out a carjacking? Like that seems like a lie. But that’s the reality. And that’s why there is no real explanation for it, and that I’m just sort of, you know, I’m just fortunate that nobody was physically harmed and that I was able to get a chance to, you know, come home from prison, and build a life and sort of build a legacy that, I hope, is more meaningful than a crime that I committed.

MARTIN: Are you ashamed?

BETTS: I’m ashamed. Yes, I’m ashamed. I mean, I think if you’ve robbed somebody, you should be ashamed. And I think —

MARTIN: What should happen and what is, is sometimes not the case, and we could have a very long conversation about that. But I mean —

BETTS: You know, I think I carry around a deep sense of shame and I think I probably didn’t recognize my own shame until my oldest son was five.

BETTS: And a classmate told him that I went to prison and say, you know, yes, your dad went to jail for stealing a car. And he didn’t know, and then I had to talk to him about it. And that was the first time that you know, I mean, children have a cleaner, more pure sense of morals than adults, and they don’t make excuses for bad behavior of others in the same way. He just had a hard time dealing with it.

MARTIN: I guess I want to go back to being a 16-year-old sentenced to nine years in adult prison. There was the option of sending you to juvenile facility, but that did not occur. Do you remember when you realized that you’d be going to an adult prison for a decade almost as long as you’ve been alive at that point, right?

BETTS: Yes, and I remember it was May 16th when I got sentenced. May 16, 1997. And the judge said, I am under no belief that sending you to prison will help. But he sent me to prison anyway. And I was 5’5″, 125 pounds, and I had the stories in my head, you know. I had the story of “It Makes Me Want To Holler.” I had “Man child in the Promised Land” I had “Malcolm X.” I have read just all kinds of books about incarceration before this happened to me. When I first got to the jail, I read the first book I read cover to cover was Ernest Gaines, may he rest in peace. I read “A Lesson before Dying” cover to cover, so I sort of understood like what incarceration was, but finding out that I will be gone for nearly a decade. I don’t know, you just walk back to yourself, and you feel drained. And you feel like you need to find a way to deal with it. At least me, I felt like I had to find a way to deal with it, and so my way of dealing with it, I just decided I would be a writer.

MARTIN: One of the things you write a lot about in your work, in your essays, as well as in your poems is how being incarcerated follows you even after you’ve allegedly paid your debt. Why is that?

BETTS: Well, it’s that thing? I mean, I think if you asked me earlier did I feel ashamed, and I think the decision is if we allow people to admit that they feel ashamed, will we allow ourselves to forgive them for the things that they’ve done? I think the tension is between how I’m willing to allow myself to feel about the crime I committed. When I hold that mistake and that error and that failure, and I juxtapose it with all of the harms that the system has done, I juxtapose it with the fact that I was sent in prison with men and I was 16 years old, and there was never any kind of training, or like, how do you learn how to hold your tongue and be humble? And not be loud? And not be boisterous? And how do you go learn how to be respectful in an environment where people get hurt, right? Nobody had that conversation with me. And so part of me resents that and it is me figuring out how to deal with my own resentment on the latter part, also being able to hold to the fact that, like, I’ve robbed somebody, and that’s a problem. And then you take those two pieces, and you say, how can I prefer a world that really doesn’t want to say, yes, Dwayne, you robbed somebody, and we’re willing to let you go forward from here. I mean, even at every step of the way, what I want to do tomorrow is going to be something in my way, saying, well, I’m not sure if we should let you do this, because you carjacked somebody at 16, and then if they do, let me they’ll say, Dwayne, you’re an exception because you have a degree from Yale Law School. But the truth is, I could try to get a job right now at a local McDonalds, and if I admit that I have a criminal conviction, I’m less likely to get that job than I am to get a job as a professor at a local university. So it’s just this real tension between when we allow people to be truly forgiving and forgiving based on the fact that we allow them full access to society, and when we just need them to perform their guilt constantly. And then on the other hand, it’s like, when would I allow myself to be forgiven? You know, when will I not constantly feel the need to perform my guilt publicly? And I don’t have to answer actually to either one of those.

MARTIN: I was going to ask you to read an essay on reentry. How does that sound?

BETTS: Perfect. Essay on reentry. Telling a story about innocence won’t conjure acquittal and after interrogation, and handcuffs and the promises of cops blessed with an arrest before the first church service ended, I had become a felon.

BETTS: The tape recorder sparrow my song back to me, but guilt lacks and melody. Listen, who hasn’t waited for something to happen? I know folks died waiting. I know hurt is a wandering song. I was lost in my fear. Strange how violence does that makes the gun vulnerable. I couldn’t not wait. I had no idea what I was becoming. Later, in a letter, my victim tells me I was robbed there. The food was great and drinks delicious, but I was robbed there. I will consider going back. He said it as if I didn’t know why would he return to a memory like that? As if there is a kind of bliss that runs and rides shotgun with the awfulness of a pistol in a dark night. There is a Tupac song that begins with a life sentence. Imagine, I scribbled my name on a confession as if autograph in a book. Tell your mother that. Say the gun was a kiss against the sleeping man’s forehead. Say that you might have been his lover and that on a different night, he might have moaned.

MARTIN: How do you think you came to your style?

BETTS: The story and I like telling a story because this is about the power of books and the influence of books in my life as I was in solitary confinement, and you could just ask people for books, other prisoners who went in the hole, but they didn’t have a library that came to us. And men would just slide books to you and they wouldn’t know who you were, and your duty was just to give it to somebody else when you finished. And so somebody slipped me the “Black Poets” by Dudley Randall, and it just changed everything about what I thought about writing. I’ve read to poetry of Etheridge Knight and Etheridge Knight was a poet who has served time in prison. He was just fantastic, you know, and he had these poems about prison. And actually the one that hit me, you know, the first poem I read was this poem called “For Freckle Faced Gerald” and it was about a black kid named Gerald who got raped in prison. And it was a brutal and violent poem. But there was also more than that, though. It was written in the 60s, and Gerald got locked up at the juvenile and one of the lines was 16 years, he hadn’t even done a good job on his voice, and I had gotten locked up when I was 16, and so reading the poem, like allowed me to situate myself in a national historical narrative about incarceration in America. And I was able to be a bit less like self-centered, because I thought that me and my friends that we were this sort of cadre of young people who were banded. And then I started to think, this is a historical problem, and for a writer to make me think differently about how I saw myself in the world. I just thought this is what I want to be. And when I decided, I said I’m a poet, and from that point forward, I wrote poetry and wrote it and not imagining writing a book, not imagining being on PBS, not imagining meeting you, like we knew who you were, we were listening to NPR, listening to the radio. You know, we had a sense of what the world was like. But I never imagined that that would be a world that I was a part of. I just thought, man, I could figure some of this stuff out on a paper and read it on a yacht.

MARTIN: I just want to show this, is that you got these poems that are redacted from —

BETTS: A legal document.

MARTIN: Legal documents. These are actual legal documents, and you created a poem out of it. I’m just going to ask you just to read these just maybe just read these two pages. Do you want to do that?

BETTS: Yes. So these are about money bill, basically, and this is the Houston case, and it was — these cases were done by the Civil Rights Corps, a nonprofit, a fight against mass incarceration, and one of the ways they’ve done it is to sort of challenge the criminal bail system in the United States by suing different cities and localities for their bail practices. And so how do I turn this really powerful legal document into something that actually speaks to people? I thought I’m going to take all the words that’s already there. I won’t change any words, but I’ll redact it and I’ll redact the things that was superfluous so that the only thing that remains this kind of poetry that tells the tale, as I read. The system exists to prejudice. The bail system has proven and extremely effective tool, some criminal defendants remain, despite being able to bail out. The defendants, their contacts chosen not to post bond due to health. Parent wants to stop drug use, or the defendant wishes to remain. The jail provides shelter, multiple meals per day, medical services. Plaintiffs’ claims should be dismissed. Plaintiffs are asking court to intervene. Plaintiffs’ claims should also be dismissed. Judges are not the creators of bail. The judges are immune from damages. And so those two pages are the judges explaining why bail is okay, and I just thought that was just really disturbing for a judge to say, people want healthcare. They want three meals a day, and that’s why bail is legitimate.

BETTS: And that’s just a sort of contrary to any idea that I think we should hold our freedom and due process and innocence until proven guilty.

MARTIN: In one way, we live in a cruel time where there is not a lot of sympathy, particularly at the highest levels for people who are incarcerated. There’s a lot of demeaning language directed at people. On the other hand, though, there’s an awareness of things that people weren’t talking about when you were 16, like the brain development of 16-year-olds. The fact that as you pointed out, 16 year olds can’t serve on jury. So how are they being judged by the jury of their peers? There’s even a movement to allow 16 year olds to vote.

BETTS: Right.

MARTIN: As you are aware of so. So when you put it together, are you, you know, how do you see it? Are you encouraged by the present moment? Are you discouraged by the present moment?

BETTS: I think the present moment is sort of complicated, right? Because in ways you know, first, the rhetoric sometimes doesn’t match the things that people do in practice. So there’s some really positive things to look for — to look towards. They’ve been raising the age for incarceration, really like all across the country. Where now most states aren’t really trying cases. Well, they still have mechanisms to track you as adults, but it’s not that automatic, you’ll be tried as an adult, if you’re 16, like it was in New York for a long time, like it was in Connecticut for a long time and North Carolina for a long time. They also have more mechanisms to allow you to — when I got tried as an adult, it was automatic, and there was nothing that my lawyer could say, no argument that he could present in front of the judge to say that Dwayne shouldn’t be tried as an adult for these reasons. Once the prosecutor made the decision, there was no looking back. And so we’ve had some change on those fronts. But I still think that most of the rhetoric has been to raise attention to the issue, but not really to develop meaningful strategies and laws to change it. Now, I feel confident, you know, Virginia — I was locked up in Virginia — the entire eight and a half years I spent in Virginia every year, we hoped that parole will return. Little did we know that for those eight and a half years, there was probably no hope. But this year, Virginia went blue, and it’s the first time in a generation it has gone blue, and there’s real hope and possibility that they’ll bring parole back, and so we’re talking about bringing back measures that allow people to say, listen, I made a mistake, but I don’t think that I should spend the rest of my life in prison.

MARTIN: Before we let you go, what would you say to people who say I just don’t — I don’t care. You know, people did something wrong. They should just stay there, and they’re not a priority for me, for people who just say, I just — I don’t care. What do you say?

BETTS: I will say that, I’ve been like all across the country. And I’ve done events at universities all across the country and the thing that always gives me hope is I’ll be in a room filled with white people, wondering why they invited me? And I’ll just read my poems and answer the questions. And there will always be two or three people that come up to me and say, you know, my dad was locked up my whole life. Oh, you know, my uncle wasn’t locked up, but he was abusing my aunt, and he was only then locked up about four. So I think what happens is, I am convinced that I was in North Country, and it was a mass incarceration social justice conference put on by a church there. Right? And, you know, this is rural white America, and they are putting on a conference to think about issues of mass incarceration, basically in upstate New York. And so what I would say to people is that this is not quite as capped a black American problem. This is an American problem. By percentage, we are overly represented in the criminal justice system, but there’s more white people incarcerated than black people. Right? And I think that to that person, I will say that once that really, we’re not talking about the other. We’re talking about our cousins, our uncles, our aunts. We’re talking about the friends of our cousins, our uncles, and our aunts. I mean, this problem has gotten so enormous with more than, like 90 million people with a criminal record, that everybody has no more than three degrees of separation from somebody who has a criminal record. And if they admit that to themselves, and they read “Felon” or a recent other literature, I think it becomes obvious, and it just doesn’t hurt us. It makes us better to find ways to treat each other more justly.

MARTIN: Reginald Dwayne Betts. Thank you so much for talking with us.

BETTS: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

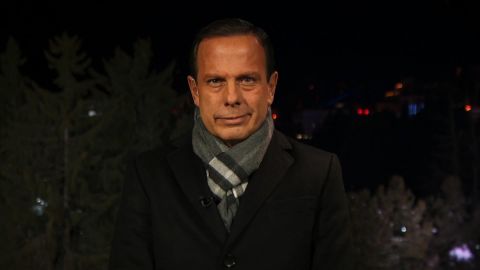

Danny Weiss and Jonathan Burks offer their perspectives on the Senate impeachment trial. João Doria, governor of São Paulo, Brazil, joins the program from the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland to discuss the climate crisis. Poet Reginald Dwayne Betts tells Michel Martin how he discovered the power of words while incarcerated.

LEARN MORE