Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR (voice over): A violent election campaign as Federal forces are deployed against protesters and coronavirus runs rampant.

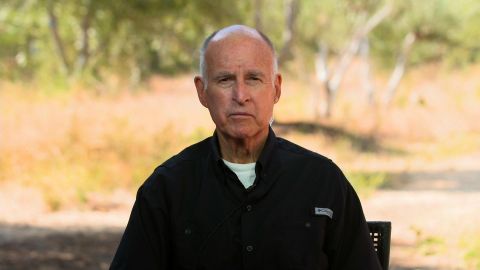

The former California Governor Jerry Brown joins us.

Then, can Germany’s post war example contain lessons for U.S. police reform? Frank conversation with a Professor at their police university and

a former American cop and sociologist.

Plus —

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: We’re really seeing an incredible shrinkage and decimation of the local news. You know, the whole local news system.

AMANPOUR (voice over): A crisis in local news opens the door to hyper partisan political sites. “The Washington Post’s” Margaret Sullivan tells

Michelle Martin about the threat this poses to democracy.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

It is just 99 days before America votes, and this is the context. Federal officers continue a violent faceoff with protesters in Portland, which is

triggering protests in other cities across the United States.

These are sites that take on an extra poignancy today, as one of the last of America’s great Civil Rights leaders, Congressman John Lewis lies in

state at the Capitol rotunda.

The first black congressman to be honored like this and in an extraordinary extra measure, Lewis’s coffin is also moving outside to the steps of the

Capitol today and Tuesday so that Americans can come and pay their respects while also social distancing.

Coronavirus in the U.S. is now claiming more than a thousand deaths per day and infections have passed the four million mark.

After a strong start tackling the pandemic, California now rates as the worst hit in the country. Joining me for more on all of this is the former

California Governor Jerry Brown.

Governor Brown welcome to the program. Let me first start with Congressman Lewis. It just is the most extraordinary sight as today, his cortege has

passed over the painted Black Lives Matter on the road in Washington.

He’ll be lying in state for the next couple of days and there are Federal or official outriders escorting him, and you remember all those years ago,

obviously, he was brutalized by law enforcement when he tried to cross the Selma Bridge, just what does all this mean to you today?

JERRY BROWN, FORMER CALIFORNIA GOVERNOR: Well, this is a memory, an icon of one of the great moments in American history, when after years of Jim

Crow and discrimination in the South, the Freedom Riders, the protesters who really turned the country around won the congressional enactment of the

Voting Rights Act and the Public Accommodations Act.

John Lewis, he was there. He lived it and he lived right up into just a few days ago, fighting the good cause, but symbolizing that better spirit of

America that can change when we need to change and do the right thing.

So he was a great person himself, but he also stood for something profoundly important to the American nation.

AMANPOUR: So given that all of this is happening now, it is an incredible confluence of events, the brutal murder of George Floyd, the death of John

Lewis, the protests all over the country for racial justice, and on top of that, add, Federal forces being unleashed on these protesters in various

cities.

Talk to me about what’s going on. The President has also named Oakland as one city, obviously in California, you once were Mayor there, where he may

send Federal forces. What is your reaction to that?

BROWN: Well, Trump is so bizarre and so deviant in so many ways. This is just another very alarming chapter in his very checkered career.

Look, sending armed officials of the Federal government to cities in America to do what is essentially local police work is ominous. It’s

unprecedented and certainly not needed.

Look, Oakland, I was there. They’ve got several hundred anarchists that love to break windows, light fires and protest, but local people can handle

it.

BROWN: When the Federal government uses the Army or uses some other militia equivalent, it really does kind of conjure up some kind of East

European dictatorship from another era.

Trump has pushed the boundaries in so many ways. This one is particularly ominous.

AMANPOUR: Do you think that it is an election ploy as some have suggested? Or do you think in some of these places like for instance, Portland has

declared a state of riot now, do you think some of these places want these Federal forces or do you think it is just an election ploy on behalf of the

President?

BROWN: No, look, I’ve been in politics 50 years. I think I understand the political mind. This is pure politics. It’s a move, probably reminiscent of

Richard Nixon in ’68 when we had all the protests and riots and all these civil disturbances. Nixon was very aware of that. He played it like a

violin, and he won in 1968.

So Trump is aware of that history and he is trying to do the same thing. Look, California’s had riots. Before we had the Watts riots. We had

protests and riots in 1992. Even the National Guard of California has called that, by the Governor, by the President.

A fundamental principle of America is federalism, and the most quintessentially local responsibility is public order and safety. The

people of California, the people of Portland, Oakland, they can handle this. This is pure politics, but it’s dangerous assertion of Federal

authority in a way that is very contrary to our historic framework and what is divided responsibility between state, Federal, and local.

AMANPOUR: Governor, you said that Richard Nixon played the law enforcement card and he won. Do you think President Trump will be it will win?

BROWN: No one knows. I think it’s an election that cannot be predicted today. But I do think Trump by his behavior toward women, toward his

office, towards the truth with his thousands of lies, I don’t see where the boundaries are in this man’s character.

So I think he’s going to try to exploit it. But I think America, Joe Biden, the decency of the people will see through what is really not just shoddy

tactics, but very dangerous and un-American maneuvers.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you, you know, Californians voted in the primaries certainly in the California primary, overwhelmingly for Bernie Sanders.

And, you know, Joe Biden made it through to being the presumptive nominee, and now Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden are working together.

I’ve had Bernie Sanders, the senator on the program, and he’s all in for Joe, as he calls him, and they’ve come together with this taskforce. How

important is that? Or how different is that? Do you feel that that will bring all the different elements of the Democratic you know, spectrum to

the polls on Election Day?

BROWN: I think so. Look, the basis they call it, the activist Democrats, the more liberal progressive, tending to the left that Bernie represented

so well, they’re not going to see another four years of Trump, and they can help — they’re going to vote.

The key voter bloc that Joe Biden has to worry about are those working class voters who have really been harmed by the neoliberalism, global

export of jobs, the hollowing out of the manufacturing base in Pennsylvania and Ohio and Wisconsin and Michigan.

That is where the battleground is. I think, the more loyal Democrats, those on the left, they are there. What is needed are the people who are

independent, who are worried, whose lives have been completely disrupted and disoriented by this global economy that has been powerful, but

powerfully disrupting to millions of ordinary Americans.

AMANPOUR: What would you say — how would you describe Vice President Biden? Some say that he has got qualities or both of you share fairly

similar qualities in the regard that you both do pragmatic bipartisan deal making. You’re both pretty personally frugal. You don’t take big limousines

and, you know, take whole entourages on private planes.

You’re quite you know, prudent fiscally in your in your own states. What strengths do you recognize in him, if any, that are required for this

moment, should he win?

BROWN: What I see in Joe Biden, I see a lot of similarities. We both came from Irish Catholic families. He started in politics very young in life,

about the same time I did.

BROWN: Look this a decent guy who embodies traditional America, the pillars of our culture, our history, our society. He’s a down to earth kind

of guy. He’s not an ideologue.

He’s not some strange being off on one of the fringes left or right. He’s right where America is, and I think his decency, his commonsense, I think

that’s what the world needs.

The presidency usually swings from one type to the other, and all the Trump exoticism now should be replaced by the down to earth-ism of Joe Biden.

AMANPOUR: You know, the Federal government has — well, Congress has been passing on bills, stimulus and sort of relief bills to try to help people

who are undergoing the terrible economic results of the coronavirus pandemic.

But this sort of unemployment benefit, so to speak, is due to expire this coming Friday, and there still isn’t a meeting of the minds between

Democrats and Republicans on how to extend those or what to do next.

What do you fear might happen to ordinary people, if they can’t get to a deal? What kind of a deal should they try to strike?

BROWN: Look, the Federal government is dedicated by the Constitution to promoting the general welfare and the general welfare is being devastated.

Tens of millions of people, the poorest people who are doing the work, the hard work, working in the nursing homes, taking care of old people, the

back of restaurants, doing the stuff the essential work, they’re the ones disproportionally that are getting the pandemic.

And where does this all lead back to? The President. The most fundamental responsibility is the safety of the American people. Trump failed, and he

failed in not just in providing income maintenance, but he didn’t do the testing.

He should have done like Roosevelt. In one day, we went from private cars to tanks and planes and liberty ships. We could have had the tens of

millions of tests every day if Trump had mobilized the manufacturing capacity. He didn’t do that.

And so because we missed that, COVID has gotten out of hand. We must test, we must quarantine, and we must take care of those whose families are

devastated by the lack of income.

Only the President and the Congress working together can do that. That’s what I want to see, not fighting Republicans and Democrats. This is a time

of national emergency, and we need the President to mobilize manufacturing capacity to do the testing.

If you can’t identify who has the virus, then you have to lock everybody down. That’s a depression. You’ve got to find the people carrying the

virus, quarantine them for two weeks and be on with the business of America. It can be done, but it takes a real change on the part of the

White House.

AMANPOUR: So can I ask you about your own state because everybody saw your successor, Governor Newsom, you know, knocking down early, doing all the

measures that should have been done and getting the virus under control in your state.

And then it started to come all the way back and now as I said, you know, California has the highest rate right now. What went wrong? It started

under, you know, lifting lockdown and the whole thing has just sort of got terrible. There are massive new lockdowns across your state now.

BROWN: Look, it’s real simple. You have to identify who has got the virus. That was never done completely, and it wasn’t done because the President

didn’t mobilize the capacity of America to make the tens of millions of test kits that we need every day.

So if you don’t know who has the virus, you’ve got to lock everybody in. When you do that, you create absolute havoc and economic devastation. So

you back off.

When you back off of you’re staying at home, sitting and sheltering in place, then the virus goes wild. And then you back off again. There’s no

way to get out of this, lock them up, let them out, lock them up again.

We must be able to find those who carry the virus, quarantine them for a few weeks, take care of those who can’t afford the financial stress by

helping their families. It’s real simple, and then everyone wear a mask, as a matter of mandatory practice.

If you do that, we will get it done. But I’ll tell you, we’re still missing some elements and those elements have to be done nationally, not just

locally.

AMANPOUR: So Governor, you know, you left office with huge cute kudos and high praise for how you dealt with California in all areas. But I want to

ask you because it’s really important.

AMANPOUR: Your predecessor, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger had, in fact, given millions and millions and millions to stockpiling things like the N-

95 masks, portable ventilators, thousands of sets for mobile beds, hospital beds, in the case of a pandemic or fires that California has or

earthquakes.

And then you, you know, defunded all of that when the recession hit after the financial crisis. Talk to me about that. Talk to me about why it’s

impossible to be able to do what’s necessary, given, well, I mean, it just seems like, it was all there and then you sort of defunded it.

BROWN: That’s a fairy tale. It wasn’t all there. We did make a lot of —

AMANPOUR: But that’s what the “Los Angeles Times” says.

BROWN: Well, I don’t care what the “Los Angeles Times” and everybody else says, I know the facts. I was Governor. I was Attorney General before that.

Yes, we cut back.

But remember, that was 10 years ago. We’ve had a lot of time to recover and what’s missing is not a small number of masks that California had in the

early part of this century. We need billions of test kits and masks, and they need to be manufactured now. And that can only be done with a national

push, starting with the President and the Congress.

So that is a bit of a diversionary factoid, that doesn’t really go to the dilemma where we are and that is a raging virus without the ability to

identify who is spreading it, and without that ability, then you are forced to want to put everyone in quarantine.

But you can’t do that economically without an absolute disaster. And we’re caught in the middle of an absolutely unmanageable problem that I believe

the governor is struggling with, but only if the President and the Congress come to the rescue can we really get out of this mess.

AMANPOUR: So let me ask you about the impact of coronavirus on the election. You know, there’s all sorts of concerns among certainly,

Democrats about what may or may not happen around the election because of coronavirus, whether they’ll be sort of, you know, the President just

talked about not particularly liking the mail ballot system.

He said that he — well, he refused to say to Chris Wallace of Fox News, whether he’d leave the White House if in fact, he lost, and I’ve been

talking to actually former Republican governors and others who are concerned about the current state of play in the U.S. Just going back to

these Federal forces camouflaged, you know, pretty much unknown who they are in various cities. This is what former Senator William Cohen said to

me.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WILLIAM COHEN, FORMER U.S. SENATOR: I think President Trump is taking us down the road to tyranny, to one man rule, to try and replicate what he

sees as a positive in Moscow with President Putin, or in Turkey with President Erdogan or over in China or North Korea.

I think he wants to add one man rule is not the law, the rule of law, but just the opposite. It’s the law of rule where he only can make decisions.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Governor, you know, he’s talking about all sorts of foreign dictators and authoritarian leaders and what’s happening in the U.S. is

being watched here overseas very carefully with a degree of shock.

Do you share his concern that it’s really serious and that this idea of authoritarianism or chipping away at the fundamentals of democracy is

possible in a country like the United States?

BROWN: I certainly think it’s possible. I think Senator Cohen gave the most ominous interpretation. But it’s not completely farfetched.

We’ve seen Poland, Hungary going the authoritarian route. So it’s not just the former, you know, just Russia and Turkey. Look, we’re in a very

disruptive period. People are desperate. You see it in the reaction on the streets. You see it in voting behavior. You see it in just this pandemic.

It’s very unpredictable.

So I think the remedy is for people to come out in massive numbers, and repudiate the man who is number one, responsible. He is blaming China,

which concealed this virus for five weeks. Well, he’s dissembled for five months, and he’s the only one that can invoke the war production law so

that we can make the manufacturers produce the billions of masks and test kits that American now needs.

So I think, yes, we may not see actual ballot the way we want, we might not see people voting as often. I mean as freely as we want, but I think if

enough people look at what Trump is doing and what’s going on, and they come out in the numbers, there’ll be so overwhelming that the outcome will

have no doubts. But is there a risk? You bet there is a risk.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you very quick answer from you. Obviously, climate is your life’s work. And Joe Biden has put a huge, huge, you know, $2

trillion, you know, plan to try to deal with all of this and it’s got a lot of kudos.

Are you confident that this administration, which has rolled it back if it’s replaced by Biden, climate will be central to the building back better

post pandemic?

BROWN: I hope so. Given the inertia all over the world in dealing forthrightly with reducing carbon emissions, you don’t want to be too glib

in saying, oh, Joe will take care of it.

The Democrats and Joe Biden are committed. But we need the Congress. We need business. We need the American people. We need this transition. We

only have 20 to 30 years before we have to be at net zero carbon emissions. That’s just a stupendous transformation of the world not just America.

We’ve got to work with China, and India, and Europe and all of these other countries. So it’s huge, but Biden is committed. He understands the

problem, and he’s the best chance we got.

AMANPOUR: Governor Jerry Brown, thank you for joining us from California.

Now, the brutal police killings, the uprising for racial justice, and now the authoritarian leading deployment of camouflaged Federal forces to crush

the protests have all shaken the world, but perhaps none more than Germany, which has spent seven decades trying to eradicate and doing so it’s Nazi

past.

The major news weekly “Der Spiegel” devoted a recent cover to this image calling the U.S. President a quote “fire devil.”

After World War II, Germany completely demilitarized and depoliticized its law enforcement. That had not only policed the horrors of the Holocaust,

but helped develop them, too.

As the United States seeks to reform its police force, what can it learn from this experience?

Joining me now from Berlin is Joachim Kersten, Chair of Police Science at the German Police University. And from the State of Maine on the East

Coast, Neil Gross, a former police officer and Professor of Sociology. Welcome. Welcome to you both. Could I first ask you Mr. Kersten? Well, how

did it start?

When you look at what’s happening in the United States right now, what goes through your mind? I mean, do you think, well, yes, the U.S. has to have a

big, you know, reform. We in Germany did it under different circumstances. What goes through your mind about what might be some lessons learned?

JOACHIM KERSTEN, CHAIR OF POLICE SCIENCE, GERMAN POLICE UNIVERSITY: Well, for one thing, Christiane, my generation was very much looking to the U.S.

as a frame of reference in terms of culture and everything, and now what’s happening now is just the opposite. It seems to be going down the gurgler

in terms of politics, and other things, which has to do with the government of the United States right now.

And what we did in Germany, what we had to do, we didn’t want to do this, we were ordered to do by the allies, fortunately, what we did was a very

slow process.

1945 was not a blank slate. It was an authoritarian disorganized society, and in the society, authoritarian forces were very strong, and

unfortunately also beginning in the 50s, the rehiring of ex-Nazi police led to a deeply authoritarian structure in the police. And that went on into

70s when we had the student protests and everything.

And then young officers, young police started to reform from the inside. And that has also taken a while, but now I think we have a more democratic

and citizen oriented police than we ever had before with all the difficulties that we have right now.

AMANPOUR: Let me just ask you also about some of the actual, I guess, measures that were taken to sensitize new recruits to the police. I hear

that you know, some of them, maybe all of them have to go to a former concentration camp and just look and see and know what was done then.

I hear that some of the police unions organize trips to the Holocaust Memorial in Israel at Yad Vashem. Can you explain some of those sensitivity

and necessary, you know, introductions to history that your police recruits have to go through?

KERSTEN: See the the police education in Germany is very different from that of the United States in that it is very much longer and it’s very much

more sort of school or academic oriented and part of the curricula for the — at least for the silver ranks and of course, for the gold ranks in

policing is the education about the German past and the burden that Germany I think still carries, like the U.S. still carries the burden of slavery

and the Civil War.

KERSTEN: So they have classes, but then, they are young people, you know, and to sort of see what happened — what has happened under the Nazi rule

in a concentration camp is certainly helpful. But what is equally essential is that they have classes where they actually train interactive

communication with people who look different and who are different because they come from other countries and other cultures.

And that is, I think, equally important to the history lessons is to have interactive teaching when it comes to dealing with people of color, with

people who are disoriented in our in our country and there are quite a lot of them.

AMANPOUR: Let me turn to you, Neil Gross. You’ve been listening to this. You have got so much experience on the U.S. side. You’re a former police

officer yourself. You’re a Sociology Professor.

Now, some historians even in Germany say you cannot compare what happened during the Nazis and the Holocaust to what’s happening in the United

States. I wonder whether you agree with that and whether you think that America which has never institutionally confronted its slavery past should

do things among others, like what police recruits have to go through — education sensitivity — you know, there are plenty of memorials and

history that police and other law enforcement could actually learn about. Would that work in the U.S.?

NEIL GROSS, SOCIOLOGY PROFESSOR, COLBY COLLEGE: Well, I think it’s a tough question. I think that there are small scale efforts underway in a number

of departments now to expose officers to both the history of racism vis-a- vis the police, and also to its present forms.

You see programs popping up in, you know, in cities, large and small where officers are taught about the history of policing in their communities,

which they’re exposed to people who have been mistreated by the police in recent years. But these are really just drops in the bucket.

I mean, I think that for this to be a kind of meaningful change, I think we would have to move towards something more like this system of police

training that you get in Germany. I mean, here, police training, it varies from department to department, from state to state, but on average here,

officers receive about 20 weeks of training in a police academy, followed by perhaps three to 12 months of field training.

Many departments do not require officers to have Bachelor’s degrees. So it’s a very different kind of process, and I think moving toward something

like what we have in Germany, could well be a productive direction for the U.S. to go.

AMANPOUR: Could I just say, given the fact that in Germany as Joaquim just enumerated that it’s a multiyear, highly intense training, and you’ve just

said it’s, you know, potentially a year and a few weeks in the United States. That’s a pretty shocking fact there.

But also, Neil Gross, American policing has its roots, certainly, in the south, in the slavery era, in the white vigilantes that were slave patrols.

I mean, it really does matter, doesn’t it? I mean, this stuff has to be, you know, in Germany, they call it de-Nazification. There’s probably

another word that you can use in the United States.

Surely, it has to happen now, especially with all this conversation about needing massive reform.

GROSS: Oh, I think there’s no question. I think that’s right. And, you know, I think beneath the various calls you hear for police reform, for

police defunding, from some for police abolition, I think there’s a desire, you know, not just for a small shift, but a really different kind of

peaceful, you know, one that will be as concerned with the preservation of rights and with the welfare of the community as with protecting people from

crime and solving crimes.

So, I think — I think much needs to be done. And I think there are short- term steps that could be taken, as well as long-term ones.

I mean, in the short term, leaving aside the question of the broader issue of kind of racial reconciliation, I think it’s clear that we need more

restrictive use of force policies. Those are kind of obvious, but surprisingly effective, governing when police can and can’t use force.

I think we need better screening for who can become a police officer to make sure that officers with troubled pasts don’t enter the force. I think

we need routine monitoring of police interactions with citizens.

There’s surprisingly little of that in American policing today, but with body cam technology, we have the ability to figure out exactly who’s being

stopped, who’s being pulled over, how people are being treated. And that information needs to factor into personnel evaluations and performance

evaluations.

And then, I think, to come around to your question, we need many more of the trust-building workshops and community dialogue sessions that police

departments are rolling out in small pockets around the country, where people are taught about — officers are taught about things that have gone

wrong in the history of policing, including exactly the history you just described, the entanglements between law enforcement and slavery and more

recent ways in which law enforcement has essentially been wrapped up with reproducing racial inequality.

That needs to be more central to officers. So, those are things that can be done in the short term. And I think, the long-term, you’re absolutely

right. I think we need to move toward a different sort of system of police education.

I would personally favor moving police training out of specialized police academies and into four-year public universities, where, again, a system

along the lines of what has been described in Germany could very much be part of the conversation, much more academic and practical exposure to what

policing is and the heavy responsibilities that fall on officers to preserve rights.

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you both, because fast-forward to right now.

And you can see, in Germany, I understand, the emphasis a lot on de- escalating confrontations between police and whoever they’re after. In the United States, we have seen, with all the body cams and all the situations,

escalating happens very, very fast, to often tragic consequences.

Let me ask you, Professor Kersten.

I have read that German police barely draw their guns. And when they do, according to sociologists and those who treat them, they have some trauma,

they have some PTSD, they need some therapy or whatever, counseling.

Describe to me the relationship between guns and the police in Germany.

JOACHIM KERSTEN, GERMAN POLICE UNIVERSITY: Well, of course, they are armed. They have guns.

But I don’t think that the gun is anymore sort of a central symbol of police power or makes up the police identity. Many of my students — and I

have really thousands over the years, over the decades — who are very uncomfortable with their guns.

And, of course, they use them very rarely. If they use them, the police departments have to account for every bullet that has been used. There has

to have a report.

Now, if they use guns, they have to use guns, it’s a major thing. They have to report. It’s investigated and so on.

So, the whole gun thing is nothing that sort of makes up the sexy image of the masculine crime fighter. It’s quite the opposite. And, therefore, I

think that it’s really difficult to compare the cultures, because guns are a central part of American masculinist identification.

And that’s not the same, at least in mainstream society, in Germany.

Let me say one thing, Christiane, if I may. The return of history in sending militia-like forces to hunt down people of color is a very

unfortunate symbol of not coming to grips with the past of slavery and racial discrimination.

So, that is — really disturbs us when we see these images in Chicago and Portland of a paramilitary force that deals with protesting people.

And I can only agree to what the previous speaker said, that the cities like Chicago and Portland and elsewhere can deal with it. They don’t need

these aliens to come in and use force.

AMANPOUR: Yes, that was Governor Brown who said that.

KERSTEN: Yes, of course.

AMANPOUR: But let me ask you, then, because, actually, there seems to be a problem rising within some of even the elite forces in your country, where,

you know, there have been cases of far right extremists in the military and the police.

Some have hoarded weapons. Some have got explosives aligned with a political far-right movement, which has been given a lot of a lot of leeway

now with the rise of the AfD and since the 2015 migrant situation, where about a million came into the West.

How serious is the infiltration of your forces by these extremists right now, Professor Kersten?

KERSTEN: I think that that is a matter of investigation right now.

And what — to go back to the past and the past ’45 situation, police were always looking to left-wing people, to Social Democrats and trade union and

so on. They were pretty blind on the right eye for right-wing extremism.

And there have been right-wing extremists in the police organizations in the ’60s and ’70s. What is happening right now is sort of a return to the

past, and it is a reference to the past between ’33 and ’45.

So, what we can learn is, Barbara Fields, eminent historical scholar, has said that the Civil War is over in the United States. It has been won, but

with white supremacy, it has not really been over. And it pops up again. The issues pop up again.

And that is the same, in a way, in Germany, that right-wing positions and attitudes are taken into the police organization, and particularly into the

elite forces of the military, and that is a very dangerous development.

It’s good that it comes to light now and that investigations are carried out. I feel not very comfortable with these issues. And I’m really ashamed

of it, to tell you the truth, that people, police officers use Nazi symbols in whatever — social media communication and elsewhere.

AMANPOUR: Thank you both so much.

Joachim Kersten and Neil Gross, thank you both for joining us on this really important matter.

And, now, this global pandemic has hit nearly every industry, including local journalism, which was on shaky ground before coronavirus.

It’s something our next guest is deeply concerned about. Margaret Sullivan is a media columnist for “The Washington Post.”

And her new book, “Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy,” sounds the alarm on the disappearance of local media

outlets.

And, here, she’s speaking to Michel Martin about how this endangers society and what needs to happen now, before it’s too late.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Thanks, Christiane.

Margaret Sullivan, thank you so much for joining us.

MARGARET SULLIVAN, “THE WASHINGTON POST”: Thank you very much for having me.

MARTIN: You started your career at “The Buffalo News,” starting as an intern, rose to executive editor. Then you became a public editor for “The

New York Times.” Now you’re a media columnist for “The Washington Post.” So, you clearly have kind of the full sweep of the thing.

Why do you like covering the news, to the point that you have spent so many years, really your entire adult life, doing it?

SULLIVAN: Exactly.

Even before my adult life, I was actually the editor in chief of my high school paper. I mean, it just really suits me. I think it’s — it has a —

journalism and newspaper journalism, but not just newspaper journalism, has the ability to have you doing something that’s really worthwhile and even

maybe a little noble, working at one of the underpinnings of our democracy, but also in a thing that’s always interesting, where you’re always

learning.

No two days are alike. And I just — I mean, I can’t imagine doing anything else. And I can say that, while I have had a lot of tough days in

journalism, I have never had a boring day.

MARTIN: You’re talking about a lot of people’s tough days in journalism.

Your book “Ghosting the News: Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy” paints a very disturbing picture of — how bad is it?

SULLIVAN: Well, it’s worth kind of reviewing just a couple of the top-line numbers here, one of which is that, since 2004, more than 2,000 American

newspaper haves closed their doors and stopped the presses and gone out of business.

A lot of those are weeklies, but some of them are dailies, and that American newsrooms are down by about and maybe now more than half their

employment from that time, 2004. So we’re really — and this is not just about newspapers. This is newsrooms.

We’re really seeing an incredible shrinkage and decimation of the local news — you know, the whole local news system that has helped people feel

connected to their communities, like they know what’s going on, keeping track of their public officials.

All those things that we really need to be good citizens are going away. And the reason for that is that the business model, in my cases, has really

just disintegrated.

MARTIN: And what is that. What is that business model that’s disintegrated?

SULLIVAN: So, for a long time, the business model, which was highly successful, was print advertising, the car dealers, the supermarkets, the

travel agencies, on and on, and classified advertising.

If you wanted to sell something, you came to the local newspaper. That was about three-quarters of the revenue of these newspapers. And then the other

piece of it, maybe as much as a third, would come from subscriptions.

So, then, the Internet come along. People’s habits change. There are more direct and targeted ways of getting to your — for advertisers to get to

their audiences. And the whole thing started changing in the early 2000s.

Then 2008 comes along, the recession, and that really knocked newspapers for a loop. And we thought things were pretty bad, and they were, and then

much more recently, with the coronavirus pandemic, another layer of — sort of another acceleration of the pace has happened.

And Axios is reporting that 11,000 newsroom employees have lost their — or I guess news organization employees have lost their jobs since the

beginning of the pandemic. So, this is really a crisis.

And it’s also weird because people — regular people, laypeople, non- journalists, don’t really understand that it’s happening. A Pew study not too long ago said that something like 70 percent of their respondents said

they thought that local news organizations were doing fine financially.

And there’s good reason for people to think that, because they were so successful for such a long time. I think that people’s views haven’t caught

up with the reality. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to write this book, to sort of sound the alarm before it really is too late.

MARTIN: And why does this matter? I mean, really this is the crux of thing.

SULLIVAN: Yes.

MARTIN: Why does this matter? Because I think people will turn on their televisions or fire up their computers, there will be some news on it.

SULLIVAN: Absolutely.

MARTIN: There’s going to be something on it, right?

SULLIVAN: Right.

I mean, there’s a ton of national news. There’s so much national news, especially political news, coming at us at all times, that we feel daunted

by it. And I have heard, and I’m sure you have to, heard people say, I’m done with all this news. I’m turning it off and am putting myself on a news

diet.

And that is true. There is a ton of national political news and other news. But what there is less and less of all the time is that regional news,

particularly the watchdog coverage of our local public officials that keeps them honest, that tells us where our tax dollars are going, how our kids

are going to be treated in school and, more recently, the coverage of the pandemic on a local level, how — we saw “The Miami Herald” did a really

good piece the other day — and this is great local journalism — where they took the poorest zip code in the Miami metro area and drilled down

into how COVID was affecting people there.

Now, that’s not anything you’re going get from this fire hose of national information. And it’s the kind of that I think that local journalists can

do.

And, similarly, again, another great “Miami Herald” piece of reporting, the reporting about Jeffrey Epstein, the sex trafficker. Julie Brown is really

the one who took that story out of — off its deathbed and revivified it and caused a lot of justice to occur.

If we don’t have those local news outlets and those skilled reporters, we’re not going to have those stories.

MARTIN: Are we talking about local newspapers or are we talking about local journalism? Are they one and the same?

SULLIVAN: Great question. And I always try to make this distinction.

We are talking about local newspapers, but we’re also talking about — I mean, we need to be talking about all local journalists, public radio, TV

stations, newspapers, digital startups. These are all a part of the local sort of news ecosystem.

Newspapers are suffering the worst, but some of the others are really hurting too, not so much TV. TV has some other forms of revenue, which tend

to shore it up a little bit better.

But all the others, I would say, are having a really tough time right now. And local TV can do some important work, no question, but it doesn’t really

do the same kind of granular, cover the city council, develop your sources, necessarily, that newspapers are kind of built to do.

MARTIN: People are used to see their local TV folks showing up at the big stories.

They do show up at the county council meeting and so forth. What’s so terrible?

SULLIVAN: Well, it’s not that they don’t show up. And I — this is in no way putting TV reporters down, because I think they have done some really

good work, and more and more, they’re doing enterprise and investigative work.

But in general and over time, they haven’t done the same kind of daily digging, source development. They haven’t — they tend to show up places,

get the footage, maybe dig in a little bit, whereas you might — at a regional newspaper, you probably had someone who was devoted to covering

just city hall, and they had an office at city hall, and that’s what they did. It was much more likely that they were going to turn up the dirt and

get the tips because they were there all the time.

MARTIN: Can you give an example, even perhaps in your own career, of why having robust local journalists who master their beats, get to know the

story really matters, and what is lost when that is lost?

SULLIVAN: Yes.

So, just as a sort of dramatic example just sort of the numbers, if you look at Denver, Colorado, so, for many years Denver’s local news ecosystem

was dominated by two newspapers, “The Rocky Mountain News” and “The Denver Post.”

And they each had 300 people. And they were — so, 600 people in these newsrooms who were able to really spread out across the state and do really

good coverage.

Then when “The Rocky Mountain News” went out of business about 10 or 12 years ago. And now The Denver Post is owned by a hedge fund, which is a

trend that’s happened, and it’s been a really awful trend. And they’re down to well under 100. I think they may be down to under 50 in their newsroom.

So, let’s say they have 60. You’re down from 600 to 60. That is literally decimation. They’re down to a 10th.

And so can they cover things the way they used to? No, they really constant. I think one of the things that makes this hard to talk about is

that we don’t know what we don’t know.

You don’t know the stories you’re missing. But one thing that’s happened in East Lansing, Michigan, is this woman Alice Dreger decided that there

wasn’t any local coverage there, or very little. Lansing was getting covered, but not East Lansing.

So she started up this kind of amateur brigade of people, retirees and moms who worked at home and dads who worked at home, and she trained them do

solid reporting. And they have turned up a lot of news there.

And she said, you might think nothing’s happening, but when you start to dig for it, there’s actually a lot, and a lot of bad behavior on the part

of public officials.

So, when you have the people to do the work, they turn up some amazing stuff.

MARTIN: One of the points you make in your piece is that it really does — a lack of local coverage really affects people’s sense of self as citizens.

It really affects their civic engagement. It even affects their kind of willingness to participate. Why is that?

SULLIVAN: Well, I think that we need to have in communities and regions kind of a basis of facts that we all function from.

And while we might have different points of view about what to do about those facts, because we may have different political perspectives, we can

all agree that there’s erosion happening on the shore of Lake Erie, or whatever, the Great Lakes are in trouble because of pollution, whatever

that may be.

But when we’re not getting that information, we sort of retreat into our partisan corners. We become much more tribal. We don’t vote across party

lines anymore.

And, in fact, we vote less and become less politically engaged. There are studies that show this. And, interestingly, too, when local news goes away,

municipal borrowing costs actually go up. Why? Because there’s no watchdog, and there’s an assumption that — and a reasonable assumption, that

government is going to be less efficient and possibly more corrupt.

MARTIN: You write about the story of the election of Congressman Collins as an example of why local news is important. Could you talk a little bit

about that?

SULLIVAN: Sure.

So, Chris Collins, who was a congressman until quite recently in the Buffalo area, although not in Buffalo proper, but in kind of a rural and

really very Republican area that spans a number of counties in Western New York, was indicted on insider training charges.

But he was nevertheless running for reelection. And his Democratic opponent told me that, in places where the news coverage was stronger — and he

describes this as being closer into the city of Buffalo, where newspaper and TV stations and others still exist — that people were more willing to

cross the aisle and vote for a Democrat.

And he said that, as he got out into more rural areas, particularly one that’s described by the University of North Carolina as a news desert, a

place where there isn’t much, if any, local news, he said, there, people didn’t even necessarily know even that their congressman had been indicted.

Now, I have since found out that there’s a small digital in Orleans County called Orleans Hub, and they did a lot of coverage. Was that coverage

getting to the voters? I don’t know.

But there did seem to be at least an anecdotal tie between people being willing to cross the aisle and vote for someone on the other side because

they were very well-informed, vs. being in a place where there’s less local news.

And this guy, Nate McMurray, said he would tell people, you don’t want to vote for someone who’s been indicted on insider trading charges, do you?

And they would say, that’s not — what? I have never heard of that. And, anyway, it’s fake news.

So, after the election took place, and Congressman Collins did win reelection, but by a whisker. He won by one-half of 1 percent, which is far

smaller than he normally would have, because the district is so Republican.

Later, he — the case went to trial. He pleaded to two felonies, and he was sentenced to a jail term.

So, I think the more informed people are — we know this. The more informed people are, the more willing they are to at least consider crossing the

aisle to vote for someone, as opposed to staying in their tribal corners.

MARTIN: Now, I think people have become aware of, you said, hedge funds buying up these newspaper chains and then, what, doing what they do,

stripping them immediately of as much value as possible, laying off people.

But what about kind of the savior model? A number of very big money individuals have swooped in to buy certain news organizations. I think Jeff

Bezos of Amazon may be the example most people know, buying “The Washington Post.” “The Washington Post” seems to be doing well. Is that an option?

SULLIVAN: They’re — I don’t actually believe this, but there aren’t enough of those kinds of billionaires to go around.

I mean, not every place that he has a failing newspaper is going to be able to tap into those kinds of deep pockets. So it just doesn’t scale. It’s

happened in a few communities. “The L.A. Times” is owned by a rich guy right now. So is the Las Vegas newspaper. And there are a couple others.

But when you think that there are thousands of papers that have gone out of business, it’s very, very unlikely that there’s going to be a billionaire

for every one of those, or even a multimillionaire who’s willing to start spending down his money to support a failing news organization.

MARTIN: So, what’s the alternative? What’s the way forward here?

SULLIVAN: Well, the way forward is a combination of things.

It’s supporting these new organizations that are cropping up, Voice of San Diego, MinnPost in Minneapolis, Investigative Post in Buffalo, “The Texas

Tribune,” all these new places that are coming up, and they have a membership model or a philanthropy model, and trying to salvage as much as

possible local newspapers by getting people to support them, to subscribe, and hopefully to be able to help them negotiate a little bit better with

the duopoly of Facebook and Google to get some of those important digital advertising dollars.

So, it has to be a patch work of answers, also supporting public radio, also supporting TV stations, or being interested in them. It’s a lot of

different things. It’s not going to be one answer. And I wish there could be a single great answer, but there just isn’t.

MARTIN: Margaret Sullivan, thank you so much for talking with us.

SULLIVAN: Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate being able to discuss this.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And so important to really, really know about all of this.

Finally, one person’s forgotten laundry is another’s fashion show, or at least it is for this stylish Taiwanese couple.

Mr. Chang, who is 83, and Ms. Hsu, who is 84, have shot to Instagram fame for modeling people’s long-left garments. They run Wansho Laundry in

Central Taiwan, which, like many businesses, has been hit by the coronavirus pandemic. But their grandson came up with this novel way of

attracting new customers, and making us all smile in the process.

That is it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me and the show on Twitter. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END