Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello everyone and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SEN. MITCH MCCONNELL (R-KY): The eyes are on the Senate. The country is watching to see if we can rise to the occasion.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR (voice over): Opening arguments begin in the Senate and the world watches a chamber deeply divided. I ask former Chiefs of Staff from both

sides of the aisle what’s ahead.

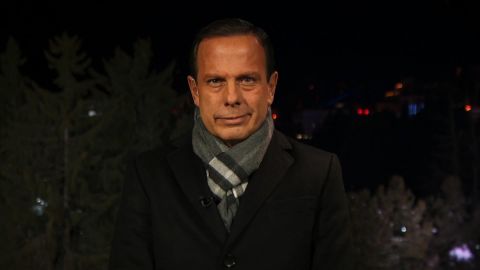

Then, climate change takes center stage at Davos. While many world leaders still refuse to act, the Governor of San Paulo talks to me about the fate

of the Amazon rainforest.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS, AUTHOR: I decided to be a writer because I was incarcerated.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR (voice over): From prison to poetry, how acclaimed writer Reginald Dwayne Betts used words to turn his life around.

AMANPOUR (on camera): Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York.

Democrats and Republicans are laying out their opening arguments for and against the impeachment of President Trump in a process that will last

several days in the Senate.

It comes after a marathon debate on the rules of the trial, which so far has resulted in Republicans blocking every attempt by Democrats to subpoena

new witnesses and evidence.

Indeed, President Trump doubled down from Davos.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

DONALD TRUMP, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES: We’re doing very well. I got to watch enough. I thought our team did a very good job, but honestly, we

have all the material, they don’t have the material.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, in response to that, the Democratic Managers of the Senate trial said the President Trump shouldn’t really be bragging about that.

Now, the very partisan nature of this battle is on display from the very start, as a Supreme Court Justice berated the senators on both sides

scolding them for their lack of decorum on the Senate floor.

Now, two Chiefs of Staff to House Speakers from both sides of the aisle join me now to delve deeper.

Danny Weiss, who worked for the current House Speaker, the Democrat Nancy Pelosi and Jonathan Burks who worked for the former Speaker, Republican

Paul Ryan.

Gentlemen, welcome to the program, and as this process unfolds, I just want to ask you first and foremost, first to you, Jonathan Burks, without, was

that wise of President Trump right in the middle of a contentious battle over evidence and witnesses and all the rest of it to say we’ve got it all

and they don’t have any of it?

JONATHAN BURKS, FORMER CHIEF OF STAFF TO HOUSE SPEAKER PAUL RYAN: Well, you know, I think it really speaks to a moment we’re in where there’s such

intense hyper partisanship that each side is we lost the ability to communicate with each other.

And so you know, the President and the President’s team are communicating to the President’s base, just as the Democrats and the House Managers are

communicating almost entirely to the Democratic base.

And so it’s just one of those things where we don’t have a very good dialogue across that’s to convince anybody who isn’t already in one’s camp.

AMANPOUR: Right. That may be, but I mean, given that this is a trial, I mean, it’s not a trial-trial is we would know it in a court, et cetera. But

it is a trial. I mean, that could be used against, right?

I mean, one of the Articles of Impeachment is about obstructing Congress.

BURKS: Well, what I took him to the mean by that he has it all is that they have all the best arguments. I didn’t take his comment to mean that

they had, you know, some materials they’re withholding from Congress.

But you know, the President says a lot of things that — he is a relatively undisciplined speaker and so that’s just one of the realities of politics

in D.C. today.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me then turn to you, Mr. Weiss, an undisciplined speaker. Do you think it was wise and can the Democrats make hay out of

what the President said regarding the evidence?

DANNY WEISS, FORMER CHIEF OF STAFF TO HOUSE SPEAKER NANCY PELOSI: I would not. If I would have been as Attorney, I certainly would not have

recommended that he say that, no.

My interpretation of what he said is that, in fact, he knows exactly what occurred. He and his team at the White House have all the evidence, and

they have kept it from the Congress, and therefore you have the charges of obstruction of Congress.

So I think he was referring very specifically to the information and materials that he is preventing the Congress from having and that’s what

the, you know, the second Article of Impeachment is about.

The president is an undisciplined speaker, but it’s interesting. Sometimes, he is brutally honest. Like when he said to the Russians, if you have

Hillary Clinton’s e-mails, you know, turn them over. And when he asked China to investigate Biden and when he asked Ukraine to investigate Biden,

so sometimes he can be brutally honest even though, he’s been found to be President who’s lied, probably more than any other President in our

history.

AMANPOUR: So how will this bout of honesty about having all the material do you think — how will that play out? As you can see, I mean, you know,

Jonathan has said everybody can see that is a very partisan battle. Each side playing, as he says to their base, but in this quasi-legal format, can

that be used, do you think?

WEISS: We’ll see. Over the next several days, the House Managers are going to continue to do what they did very smartly last night.

Last night, they essentially prosecuted President Trump on the two Articles of Impeachment for abusing his power and obstructing Congress, and at the

same time, they made it clear that there’s a raft of evidence and documents and witnesses that need to be heard to make this case even more clear.

They certainly never indicated that the case is not clear with the evidence that exists. They can add the President’s comments to their remarks over

the next three days, and I would not be surprised if they do.

One of the House Managers, Val Demings has already done that. So I would expect to see that, but they very smartly last night prosecuted Donald

Trump for these egregious actions.

And at the same time made it clear there’s more to learn.

AMANPOUR: Well, he also — President Trump responded to a journalist question about whether all of this is an impeachable offense. They asked

him about, you know, what might — what precedents it might set for the future? Let me just play this little snippet of what he said about the

process in general.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

QUESTION: Is abuse of power an impeachable offense?

TRUMP: Well, you have to talk to the lawyers about it. But I will tell you, there is nothing here. The best lawyers in the world have looked at

it, the Department of Justice has looked at it, given it a sign off. There was nothing wrong.

QUESTION: So for future President, is abuse of power an impeachable offense?

TRUMP: Well, it depends. But if you take a look at this, and from what everybody tells me, all I do is — I’m honest. I make great deals.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: All right, Jonathan Burks, interpret that for us, please.

BURKS: Well, you know, I think he’s made a correct point that whether abuse of power is impeachable is really a decision that’s dependent on what

435 people in the House determine. And then whether it’s removable is dependent on 100 people in the Senate determine.

Ultimately, these are political decisions that are made by politicians in the moment. And so, you know, it’s not a sort of legal standard that’s held

up and immutable overtime, it really is a political standard that is applied, and one can disagree with how it is being applied today or how it

was applied in the Clinton case or how it was implied in the Johnson impeachment.

But the reality is that, it’s always been a political decision, it’s always going to be a political decision.

AMANPOUR: Danny Weiss, the President seem to be again, you know, in a burst of honesty, and sort of recognizing his strengths, I make great

deals, he says, and that’s been his selling point as a real estate developer up until now.

But he is basically — is he also saying that, from our point of view, I might have done what I did, but it’s not a crime.

WEISS: Well, The President has admitted, he has confessed to what he did. He tried to shake down the Ukrainian President to help him win the 2020

election by starting an investigation against Joe Biden, his opponent, so he has confessed already.

There are no constitutional scholars who believe that an actual crime — a crime that would be tried in a court had to be committed in order to be

impeached. Even Jonathan Turley, the attorney that the Republicans used in the Judiciary Committee hearings stated in “The Washington Post” last night

and this morning, that it does not have to be a crime to be an impeachable offense.

So that’s just a ridiculous argument. It is interesting, you know, one of the thing — Trump does a number of things that, you know, we’re all

becoming all too familiar with. One is sometimes as I said, be brutally honest. The other is to say exactly what’s opposite of the truth.

So this morning when he said, I tell the truth, I make great deals. I mean, people have counted more lies from this President, as I said, than anyone

else. So it is interesting to hear him sort of acknowledge that he is a liar by saying that he tells the truth.

AMANPOUR: Well, it’s that kind of — it’s that kind of era that we live in. I know, it’s a little bit sort of difficult to get your mind around it.

But I just want to ask the two of you, because you both, as I said, were Chiefs of Staff to different House Speakers, different sides of the aisle –

– Nancy Pelosi and Paul Ryan.

I just want to play something that’s, you know, happened at the very outset of this, but nonetheless, struck a lot of Americans and people around the

world about the partisan nature of this and about what the Senate has descended into in terms of a deliberative body. This is what the Chief

Justice said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOHN ROBERTS, CHIEF JUSTICE, U.S. SUPREME COURT: I think it is appropriate at this point for me to admonish both the House Managers and the

President’s counsel in equal terms, to remember that they are addressing the world’s greatest deliberative body.

ROBERTS: One reason it has earned that title is because its members avoid speaking in a manner and using language that is not conducive to civil

discourse.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, that was a telling off, and I guess I want to ask you, from your perspective, during your time as Chief of Staff to the two

Speakers, was it different? Was it better? Is it getting exponentially worse? About debates, even when you have big disagreements?

BURKS: Well, you know, I think the challenge has always been that talking across the aisle is a skill that is atrophying for so many members. The

reality is we don’t know how to make convincing arguments to each other.

You know, if I were a Republican listening to the arguments that the House Managers made yesterday, I would find none of it persuasive, and I’m sure

the same is true of the arguments that the President’s counsels were making, in terms of a Democratic audience.

And so the challenge that we all have, if we want Washington to work is to figure out a way to actually get communicate in a way that we’re actually

heard by those who don’t already agree with us.

And so what you’re seeing in terms of stability, what you’re seeing in terms of decorum is just an artifact of a larger and longer term problem

that we’ve had in terms of members not knowing how to really engage each other.

WEISS: I would mostly agree with what Jonathan said and definitely, debate in Washington has atrophied. You know, I think the rise of social media and

certain politics that began in my opinion, when Speaker Gingrich was in charge, things have really atrophied over the years and some members don’t

want to be here anymore because of that.

When Jonathan, I both served together in Congress, we managed to make time to talk with each other on a regular basis privately, and just to keep open

lines of communication. It’s very difficult to do that publicly, and that really is a shame.

You know, now the public is in a difficult place. They’re going to have to try to pay attention, try to avoid the fake news. Pay attention to the real

news, decide which is which, and that’s becoming increasingly blurred. Unfortunately, I think President Trump is adding to that in a very

significant way.

AMANPOUR: So can I just ask you then, I was going to point out to our viewers that, you know, you both are incredibly, you know, showing great

sort of moderation and decorum and talking, like you just described you used to do and it’s not so much possible anymore.

We don’t see it on the cable networks, either today, even outside of you know, of Congress. But I want to ask you, from the Democratic point of

view, this business of people’s attention, you can see that the polls have barely moved since the whole impeachment thing began. There was a big spike

at the beginning, and it sort of stayed pretty much unchanged, despite all the evidence, all the testimony all the weeks and months of public

hearings.

That must play against the Democrats, Danny Weiss, no? I mean, surely they want to make their case to the American people who are not particularly

paying attention.

WEISS: Well, yes, it is a — it’s difficult to communicate with the vast majority of Americans. People are busy working, you know, doing their daily

lives. People find different ways to pay attention. They either do it through social media, they get their news through Facebook and Twitter, or

they may actually watch the local evening news.

So you’re trying to use all the spaces that you can to communicate. Hopefully a number of people who are running for office are going to make

convincing arguments. You know, I think what the Democrats are going to want to do between now and November, is talk about three or four things.

They’re going to talk about the cost of healthcare, again, as they did in 2018. They’re going to talk about the importance of raising people’s wages,

and they’re going to talk about a few new issues that they didn’t really talk about in 2018, such as gun violence and climate.

The last thing they’re going to talk about, again, is corruption. That was a very powerful message in 2018. It really resonated with people. Democrats

took back the majority in the House partly as a result of that message and this impeachment activity fits into the corruption message.

AMANPOUR: And just to follow on, I want to turn to Jonathan for the moment. You know, obviously the Democrats are hoping that a number, they need four

Republicans might in some form or fashion along some of these issues, switch and vote with them. Do you think that that’s likely? And have you by

any chance been speaking to Paul Ryan, the Speaker who you were Chief of Staff for, regarding this trial? What’s his view?

BURKS: Yes, I haven’t talked to Paul about the trial, particularly and even if I had, you know, the relationship we have requires that I keep our

conversations private.

But, you know, I think there’s a very, very real chance that some members decide that they do want to hear testimony or that they do want to see

documents.

I think the best chance of that happening is that the House Managers make a persuasive argument over the next three days about the value that would be

added.

But you know, it’s one of those things where I think there’s a hundred members of the Senate who took a solemn oath to take this exercise very

seriously and I think they’re going to do so.

You know, it’s a very torturous exercise in terms of having to sit there silently for hours and hours of presentations, and so I think it’d be wise

for both sides not to use the full 24 hours.

But, you know, I think there is certainly a possibility that following the presentations that there is a decision bad more evidence should be heard.

WEISS: If I could just add one comment to, Christiane, I’m sorry, is that I believe that the senators will do their best. But if they in fact, acquit

President Trump, without agreeing to hear this damning new evidence that has come to light, I think it will be perceived as a whitewash by a lot of

Americans.

AMANPOUR: And what do you make? What should the American people make of a very prominent Republican senator, very closely allied with the

President, Lindsey Graham, who says, you know, I’m not even going to pretend, you know, to be a fair juror.

We want — we know what’s up and we think that you know, you’re just trying to get rid of the duly-elected President, and I’m not even going to pretend

to be a fair juror.

WEISS: That’s a scandal.

AMANPOUR: I am sort of paraphrasing.

BURKS: Well, I think it really does speak to their poisoned waters in which this process began. I mean, the reality is that on Inauguration Day

in 2017, there were Democratic members of Congress calling for the President’s impeachment.

And so, you know, it’s just a historical reality that it has been a Democratic Party goal for years now to remove the President, then you have

an incredibly rushed and truncated investigation and impeachment process in the House where they didn’t even try to produce much of the evidence that

they spent the last 24 hours trying to get the Senate to insist on producing.

And so you know, it’s one of those things that if you are a member of the Senate on the Republican side, you look at this and you have to wonder how

genuine and how sort of honest the approach of House Democrats is as opposed to simply being a continuation of a multi-year effort to remove the

President that’s politically motivated.

AMANPOUR: I would like to play as we turn another little corner here, a little mashup of some of what the witnesses who came to the House hearings

on this beforehand, whether it was President Trump’s handpicked Ambassador Sondland, or the career civil servants, the career Foreign Service officers

who spoke about what was going on, in this particular case in Ukraine. Let’s just take a listen just to recap.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

GORDON SONDLAND, U.S. AMBASSADOR TO THE E.U.: Was there a quid pro quo? As I testified previously, with regard to the requested White House call and

the White House meeting? The answer is yes.

DR. FIONA HILL, FORMER NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ADVISER: If the President or anyone else impedes or subverts the national security of the United

States in order to further domestic, political or personal interests that’s more than worthy of your attention.

MARIE YOVANOVITCH, FORMER U.S. AMBASSADOR TO UKRAINE: I still find it difficult to comprehend that foreign and private interests were able to

undermine U.S. interests.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Okay, so they’re very clearly talking and concentrating on the foreign interest undermining U.S. interest, and since I know that both you

gentlemen have foreign policy experience and credentials, I want to ask you about that. And going back to the Clinton impeachment in the face of this

one.

So Clinton, we know that his poll ratings were very high throughout the process, and by and large, people basically thought if he was lying, it was

about a personal, you know, moral failing.

It seems according to the polls that people believe what President Trump is accused of doing is much, much graver and hence, his polls are not as high

and people have come out about what they think this is all about.

So I guess from that strict national security perspective, would you agree, Danny Weiss, that there is a real sort of difference in what the

impeachable crimes have been with the allegations here.

WEISS: Oh, absolutely. One of the main arguments that Democrats have been making is that the President’s actions directly affect America’s national

security.

An ally of the United States at war with Russia, over its own, over Ukrainian territory was directly affected by the President’s action for a

personal political activity. That’s very serious.

So you have the overall abuse of power, and then what it was about directly does affect the national security.

You know, the President’s polling numbers are really — they’re flat. They’ve never grown. He’s got his solid base. And he is going to probably

go into the reelection period, under 50 percent in terms of favorability, and that’s a very dangerous place for a President to be. We’ll see where it

ends up.

But he’s not growing his support, and he is maintaining his solid base with all of the antics that he does, but this is a national security issue, and

the abuse of power is really serious, and I agree with the way you characterize the Clinton trial that people looked at it, they didn’t like

it. It was unseemly.

You know, it’s really regrettable that that’s how he carried himself in office. But they did believe it was more of a personal matter.

AMANPOUR: And last word to you, Jonathan Burks. I mean, from your perspective, this is a weightier matter, wouldn’t you say? And then people

are reflecting that in the polls?

BURKS: Well, I think certainly there is, in both cases, serious allegations that are being made. In the Clinton impeachment, it was a

question of whether or not the President committed a felony by obstructing justice. So I think that’s a very serious weighty matter.

Here, you know, the allegation of abuse of power. I think that’s also a serious and weighty matter. Ultimately, though, in terms of U.S. policy

towards Ukraine, I think the facts speak for themselves in terms of the Obama administration didn’t provide legal assistance to the Ukrainian

government in their fight with Russia. The Trump administration has.

And so I think there’s been a consistent congressional policy on this that actually is carried through both administrations. And, you know, I think

there was certainly over the summer, a hiccup, in Ukraine policy in the administration, but it’s back on track and the end results have been, you

know, much sort of stronger on Ukraine policy then, frankly, they were during the Obama administration.

AMANPOUR: We’re going to have to leave it there for now. Jonathan Burks, Danny Weiss, thank you very much indeed.

WEISS: Thank you.

BURKS: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Now, while senators debate impeachment, President Trump returns from the World Economic Forum in Davos. This year, the focus there has been

climate change.

But from the White House to Australia to Brazil, leaders still are not taking the issue seriously enough, even as their countries face

catastrophic weather events.

In 2019, the number of fires in the Amazon rainforest grew by 30 percent. That’s according to data from Brazil’s National Institute for Space

Research. President Bolsonaro faced fierce worldwide criticism for is in initial response to the blazes. Now, he says he’ll create the “Amazon

Council” to protect the rain forest.

Now, Joao Doria is the governor of Sao Paulo. He opposes his president’s rollback of environmental policies. And he is joining me now from Davos.

Governor Doria, welcome to the program.

JOAO DORIA, GOVERNOR OF SAO PAULO: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So have I summed it up pretty well? What are you hearing there in Davos? And just tell me how you’re dealing with all the attention and

demand from activists, from world leaders, from the U.N., from all the NGOs to really get serious as a nation and as a world on the issue of climate

change.

DORIA: Well, I’m responsible for the government of Sao Paulo state, we respect the environment, and we have a very good relationship with the NGOs

and process to protect the environment in Sao Paulo and also, we follow the Paris Agreement in Sao Paulo.

We have no deforestation in the Atlantic Forest in Sao Paulo, and we keep our idea to protect the environment and to go our way in Sao Paulo state.

AMANPOUR: Do you find that you’re in collision course with your President who we know what he said about the environment? And also he’s

called Greta Thunberg, the activist, you know, a brat. Do you divorce yourself from that part of the President’s agenda?

DORIA: Well, I prefer to not comment about that. We are in different ways, but understand, sometimes, the position of President Bolsonaro, but we have

others and we keep ours.

AMANPOUR: All right. Well, how do you — I want to play actually something your own Economy Minister has said about the reason for a lot of

environmental degradation in the Amazon rainforest. Let’s just say a little bit about what he said there at Davos.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PAULO GUEDES, BRAZILIAN ECONOMY MINISTER: The worst enemy of the environment is poverty. People destroy environment because they need to

eat. They have other concerns, which are not the concerns of the people who already destroyed their forests. They already fought their ethnic

minorities and all these things. So it’s a very complex problem. It has no simple solution.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So Governor Doria, you know, do you agree with that? And to an extent a lot of world leaders say, listen, wait until we get to X, Y, or

Zed level of development and then we’ll deal with our environment.

Do you agree that it’s poverty that leads to the, you know, abuses in the Amazon forest, and what can be done to change that?

DORIA: Well, first to have respect over the forest, to have respect of the environment and we have respect over the public opinion in Brazil and

outside Brazil.

DORIA: Sometimes, we have no — we don’t go on the same way in this subject in Brazil. But in my position as Governor of Sao Paulo, I have to

keep my mind strictly in Sao Paulo State.

Sao Paulo State, as you know, is the largest economy in Brazil. We are responsible for 33, almost 34 percent of the Brazilian economy. We grew 2.6

percent last year, Brazil one percent.

So our government is focused on our mission in Sao Paulo, including the protection over the forest, over the Atlantic Forest and the principles and

the agreements that we follow as Paris Agreement.

AMANPOUR: So you do follow it, and you’ve said that in your state, you do follow it. But you know, the last big climate conference, which took

place in Madrid was very notable for a handful of countries or a lot of countries who actually tried to block any progress.

Let me just read — your country is one of them, so is the United States as well as Australia and Saudi Arabia, to block movement on the global carbon

market. As Governor of your state, you say you follow the Paris Accords? You know, A, do you agree with that? And B, how do you counter that? What

do you do to actually follow the Paris Accords?

DORIA: Well, we do the right things, follow the Accord and keep our political decision to protect the rainforest in Sao Paulo and to follow the

Paris Agreement.

AMANPOUR: So I’m really interested and I think a lot of people are interested because, you know, a lot of people around the world and in your

own country have their eyes on you. Because, you know, perhaps you might one day run for President. I don’t know whether you have that in mind.

But interestingly, you speak now as if on major issues, you separate from the President, whereas much earlier, you were much more in his camp.

But there are issues. I think that caused a bit of political separation. After he mocked the head of the Brazilian Bar Association, it was all about

the disappearance during the military regime. Bolsonaro has never hidden in his admiration for the regime’s record. What ultimately made you turn

against him to an extent on those issues?

DORIA: Well, once again, our position is different and we follow another position, we respect democracy. We respect the environment. We respect the

culture. We respect the dialogue, and we respect the press.

But I’m not in a good position as a Governor, to go against President Bolsonaro. And about campaign — presidential campaign, I have to tell you

that we have three years ahead. We must be focused on administration of the Sao Paulo State and I think also Mr. Bolsonaro, President of Brazil, also

to keep eyes and the full attention on administration, not on campaign. It is not time to deal and to talk about campaign — presidential campaign in

Brazil.

AMANPOUR: Okay, so let me just focus on one of the things you said, you know, we follow you know, our agenda and you mentioned freedom of the

press, as well as many other things. I know you’re the Governor. I know you’re not, you know, the President or the prosecutor or the Attorney

General, but I wonder if you can comment on basically what’s happened to Glenn Greenwald, who is as you know, a journalist.

He has the, “The Intercept,” and he has been charged with cybercrimes. There’s been an outcry of support for him here in the United States.

I guess I want to know whether there is increasingly a climate, of suppression of freedom of information in the country — freedom of the

press.

DORIA: Well, I’m happy because you give me — you’re asking me just very comfortable questions. But I have to tell you, we respect the press in Sao

Paulo. We have a good relationship with the press, and we defend the free press in Sao Paulo and in Brazil.

It’s impossible to have democracy, liberty, without press, without the rights of the press to say, to write or to produce covers about politics or

other matters. So, we respect in our state the position of the press, even if the press is against us or criticize some of our positions, it’s part of

the democracy.

AMANPOUR: In terms of the economy, I mean, one of the issues has been the economy, obviously, and it looks like your president’s poll ratings

have risen now because the economy is improving, because of the President’s agenda in trying to fight corruption and crime.

But I wonder if you can address the issues which may not be specific to your state, but it matters to the people of Brazil, and that is you know,

economic issues like automobile plants, like you know, Ford has recently closed its factory in your state. GM could do the same.

Foreign investment in Brazil has been kind of questionable and declining. Can you address those very real issues for your people in your state?

DORIA: We are. We are improving and improving fast and growing. This first year as the governor of Sao Paulo, we improved the economy. We invite

foreign investors. We opened an office in Shanghai, China. We’ve opened a new office in Dubai, Middle East, two weeks heads.

We invited the former Brazilian Finance Minister Enrique Mirelis (ph) to be our Finance Secretary. We grew 2.6 percent last year, GDP and Brazil grew

one point. We generated 300,041 new jobs in Sao Paulo state.

So we keep on this way, working hard and incentive for investments in Sao Paulo State in different areas, that’s the main reason that I am here in

Davos at this moment.

AMANPOUR: Are you concerned? I mean, might GM — are you working with GM to make sure they don’t close their plant in your state?

DORIA: Well, we work with GM and we decided together to improve employment and to keep GM in San Paulo, Brazil. And GM announced months ago, one

billion here, it’s almost $250 million in new investments in Sao Paulo, and 1,200 new employments in his factory near to Sao Paulo City.

So we keep supporting General Motors and other companies, foreign companies to keep working and working well, and growing in Sao Paulo state.

AMANPOUR: Let me just turn to President Trump because he’s been there too in Davos. Two things I want to ask, you know, some people in the past

have sort of compared you a little bit to him. You know, you’re a multimillionaire, you had your own apprentice situation going on in Sao

Paulo, and I am not sure that you like those comparisons, but how does it make you feel?

DORIA: I have no feeling about that. I do what I have to do, and I have my life. I spent 45 years in the private sector, working hard and I became a

rich person. That’s true. And now, I work for free. I have no salary as a Governor of Sao Paulo. I donate our salaries, and I love what I am doing,

protecting and helping the Brazilians in Sao Paulo, and I keep going on this way.

AMANPOUR: So let me ask you finally, on the economy, not just of your nation, but of all the world. So President Trump was there talking about

the America First agenda. And as you know, and you’ve seen, the way he operates, he often uses the threat of sanctions tariffs, you know, foreign

policy at the sort of end of the economic spear, so to speak.

How should foreign leaders deal with President Trump, when he basically says, if I don’t like what you do, or if I need you to do what I want you

to do, I will just threaten those blunt tools of sanctions and tariffs, et cetera.

DORIA: Well, I defend dialogue. Without dialogue, we have no democracy. We have no opportunities. We need dialogue between our countries. That’s not

ideological talking, it is thinking about the poverty, thinking and working to who needs government working well. So dialogue, dialogue and dialogue.

That’s the way that I defend and that’s the way that I got in Sao Paulo.

AMANPOUR: Governor Doria, thank you so much for joining us.

Now, our next guest went from jail teenager to award-winning poet. Reginald Dwayne Betts committed a carjacking in Virginia at the age of 16, and he

ended up spending over eight years in adult prison.

Since his release, he’s turned his life around. He’s earned a degree from the Yale Law School and he’s authored several critically acclaimed books.

His book “Felon” tells the story of the effects of incarceration on identity. And he told our Michel Martin, about the power of the written

word and the importance of forgiveness.

MICHEL MARTIN, AMERICAN JOURNALIST: There’s so much literature around prison life and what leads to prison. But so much of it is either people

who were falsely accused, or people who never had a chance. And the reality of it is, in your case, you’re neither, I mean, you were an honor student,

and you decided to carjack somebody along with a group of friends. Can you tell us why?

BETTS: That’s the million dollar question. And I wish I had an answer. I think one of the things that I said early on, actually, when I got locked

up, I remember having to call my mom and tell her and that was the first time that it struck me that I had no reason to be where I was.

The person I robbed, I might have gotten $10.00, but I wasn’t even thinking about money. We weren’t rich, but I didn’t need money. I wasn’t really into

joyriding, I had never really done it before.

I might have driven a call once before that night, and I only held a gun one time, and that was that time right there. So there was no rational

reason for me to do it. And I spent, you know, really the next 23 years up until this moment, trying to find a better answer for me doing it than what

I fell upon, which is simply, it was just in the realm of possibility.

And there was so many reasons for it to be in the realm of possibility, whether it was just a community that I lived in, whether it was just the

friends that I chose, whether it was just our willingness to not believe that our life was worth more and spending a huge chunk of it in prison.

But in that moment, I just — I just didn’t believe that my life was more valuable than the risk that I knew that I was taking.

MARTIN: The anniversary of the incident is right around now. Do you think about it?

BETTS: I think about it way too much. Because, you know, we all say we have moments that profoundly change our life. And we all, I think,

accumulate those moments, but that’s the saddest day that changed everything.

I’m a writer, I decided to be a writer because I was incarcerated. I write about being incarcerated. I think about who I am as a father, who I am as a

parent, who I am as a member in a community and all of that reflects on these experience that I’ve had.

I’m a lawyer, and my first introduction to the law was reading the Bill of Rights and my right to a jury of my peers as a 16-year-old and

contemplating the fact that going to prison at 16 meant that there’s no way I would ever have a jury of my peers.

And so, you know, so much of my life is sort of just invested in that moment that I’m constantly thinking about it. And you know, December 7th,

December 8th comes back around, and it makes me pause, you know, and both reflect on how I can appreciate my successes, but how it’s hard to

reconcile it.

You know, when you have so many greatest successes borne of your biggest failure, it is hard to reconcile the two sides.

MARTIN: Do you remember when you got up that morning? Like what was on your mind? Were you bored?

BETTS: No, I was with friends and I was with people I didn’t even know. I mean, that’s the thing. You know, you told a story, I was with one person

that I knew well, and three people that I didn’t know well at all.

And literally, you know, it sounds like a lie. What do you mean, you were with three people that you didn’t know and one person that you did know,

and then within a span of 45 minutes, you all went from laughing and joking and smoking a blunt to contemplating and then carrying out a carjacking?

Like that seems like a lie. But that’s the reality. And that’s why there is no real explanation for it, and that I’m just sort of, you know, I’m just

fortunate that nobody was physically harmed and that I was able to get a chance to, you know, come home from prison, and build a life and sort of

build a legacy that, I hope, is more meaningful than a crime that I committed.

MARTIN: Are you ashamed?

BETTS: I’m ashamed. Yes, I’m ashamed. I mean, I think if you’ve robbed somebody, you should be ashamed. And I think —

MARTIN: What should happen and what is, is sometimes not the case, and we could have a very long conversation about that. But I mean —

BETTS: You know, I think I carry around a deep sense of shame and I think I probably didn’t recognize my own shame until my oldest son was five.

BETTS: And a classmate told him that I went to prison and say, you know, yes, your dad went to jail for stealing a car. And he didn’t know, and then

I had to talk to him about it. And that was the first time that you know, I mean, children have a cleaner, more pure sense of morals than adults, and

they don’t make excuses for bad behavior of others in the same way. He just had a hard time dealing with it.

MARTIN: I guess I want to go back to being a 16-year-old sentenced to nine years in adult prison. There was the option of sending you to juvenile

facility, but that did not occur. Do you remember when you realized that you’d be going to an adult prison for a decade almost as long as you’ve

been alive at that point, right?

BETTS: Yes, and I remember it was May 16th when I got sentenced. May 16, 1997. And the judge said, I am under no belief that sending you to prison

will help. But he sent me to prison anyway. And I was 5’5″, 125 pounds, and I had the stories in my head, you know.

I had the story of “It Makes Me Want To Holler.” I had “Man child in the Promised Land” I had “Malcolm X.” I have read just all kinds of books about

incarceration before this happened to me.

When I first got to the jail, I read the first book I read cover to cover was Ernest Gaines, may he rest in peace. I read “A Lesson before Dying”

cover to cover, so I sort of understood like what incarceration was, but finding out that I will be gone for nearly a decade. I don’t know, you just

walk back to yourself, and you feel drained. And you feel like you need to find a way to deal with it. At least me, I felt like I had to find a way to

deal with it, and so my way of dealing with it, I just decided I would be a writer.

MARTIN: One of the things you write a lot about in your work, in your essays, as well as in your poems is how being incarcerated follows you even

after you’ve allegedly paid your debt. Why is that?

BETTS: Well, it’s that thing? I mean, I think if you asked me earlier did I feel ashamed, and I think the decision is if we allow people to admit

that they feel ashamed, will we allow ourselves to forgive them for the things that they’ve done?

I think the tension is between how I’m willing to allow myself to feel about the crime I committed. When I hold that mistake and that error and

that failure, and I juxtapose it with all of the harms that the system has done, I juxtapose it with the fact that I was sent in prison with men and I

was 16 years old, and there was never any kind of training, or like, how do you learn how to hold your tongue and be humble? And not be loud? And not

be boisterous?

And how do you go learn how to be respectful in an environment where people get hurt, right? Nobody had that conversation with me. And so part of me

resents that and it is me figuring out how to deal with my own resentment on the latter part, also being able to hold to the fact that, like, I’ve

robbed somebody, and that’s a problem.

And then you take those two pieces, and you say, how can I prefer a world that really doesn’t want to say, yes, Dwayne, you robbed somebody, and

we’re willing to let you go forward from here.

I mean, even at every step of the way, what I want to do tomorrow is going to be something in my way, saying, well, I’m not sure if we should let you

do this, because you carjacked somebody at 16, and then if they do, let me they’ll say, Dwayne, you’re an exception because you have a degree from

Yale Law School.

But the truth is, I could try to get a job right now at a local McDonalds, and if I admit that I have a criminal conviction, I’m less likely to get

that job than I am to get a job as a professor at a local university.

So it’s just this real tension between when we allow people to be truly forgiving and forgiving based on the fact that we allow them full access to

society, and when we just need them to perform their guilt constantly. And then on the other hand, it’s like, when would I allow myself to be

forgiven?

You know, when will I not constantly feel the need to perform my guilt publicly? And I don’t have to answer actually to either one of those.

MARTIN: I was going to ask you to read an essay on reentry. How does that sound?

BETTS: Perfect. Essay on reentry. Telling a story about innocence won’t conjure acquittal and after interrogation, and handcuffs and the promises

of cops blessed with an arrest before the first church service ended, I had become a felon.

BETTS: The tape recorder sparrow my song back to me, but guilt lacks and melody. Listen, who hasn’t waited for something to happen? I know folks

died waiting. I know hurt is a wandering song. I was lost in my fear.

Strange how violence does that makes the gun vulnerable. I couldn’t not wait. I had no idea what I was becoming. Later, in a letter, my victim

tells me I was robbed there. The food was great and drinks delicious, but I was robbed there. I will consider going back.

He said it as if I didn’t know why would he return to a memory like that? As if there is a kind of bliss that runs and rides shotgun with the

awfulness of a pistol in a dark night.

There is a Tupac song that begins with a life sentence. Imagine, I scribbled my name on a confession as if autograph in a book. Tell your

mother that. Say the gun was a kiss against the sleeping man’s forehead. Say that you might have been his lover and that on a different night, he

might have moaned.

MARTIN: How do you think you came to your style?

BETTS: The story and I like telling a story because this is about the power of books and the influence of books in my life as I was in solitary

confinement, and you could just ask people for books, other prisoners who went in the hole, but they didn’t have a library that came to us.

And men would just slide books to you and they wouldn’t know who you were, and your duty was just to give it to somebody else when you finished. And

so somebody slipped me the “Black Poets” by Dudley Randall, and it just changed everything about what I thought about writing. I’ve read to poetry

of Etheridge Knight and Etheridge Knight was a poet who has served time in prison. He was just fantastic, you know, and he had these poems about

prison.

And actually the one that hit me, you know, the first poem I read was this poem called “For Freckle Faced Gerald” and it was about a black kid named

Gerald who got raped in prison. And it was a brutal and violent poem. But there was also more than that, though.

It was written in the 60s, and Gerald got locked up at the juvenile and one of the lines was 16 years, he hadn’t even done a good job on his voice, and

I had gotten locked up when I was 16, and so reading the poem, like allowed me to situate myself in a national historical narrative about incarceration

in America. And I was able to be a bit less like self-centered, because I thought that me and my friends that we were this sort of cadre of young

people who were banded.

And then I started to think, this is a historical problem, and for a writer to make me think differently about how I saw myself in the world. I just

thought this is what I want to be. And when I decided, I said I’m a poet, and from that point forward, I wrote poetry and wrote it and not imagining

writing a book, not imagining being on PBS, not imagining meeting you, like we knew who you were, we were listening to NPR, listening to the radio.

You know, we had a sense of what the world was like. But I never imagined that that would be a world that I was a part of. I just thought, man, I

could figure some of this stuff out on a paper and read it on a yacht.

MARTIN: I just want to show this, is that you got these poems that are redacted from —

BETTS: A legal document.

MARTIN: Legal documents. These are actual legal documents, and you created a poem out of it. I’m just going to ask you just to read these just maybe

just read these two pages. Do you want to do that?

BETTS: Yes. So these are about money bill, basically, and this is the Houston case, and it was — these cases were done by the Civil Rights

Corps, a nonprofit, a fight against mass incarceration, and one of the ways they’ve done it is to sort of challenge the criminal bail system in the

United States by suing different cities and localities for their bail practices.

And so how do I turn this really powerful legal document into something that actually speaks to people? I thought I’m going to take all the words

that’s already there. I won’t change any words, but I’ll redact it and I’ll redact the things that was superfluous so that the only thing that remains

this kind of poetry that tells the tale, as I read.

The system exists to prejudice. The bail system has proven and extremely effective tool, some criminal defendants remain, despite being able to bail

out. The defendants, their contacts chosen not to post bond due to health. Parent wants to stop drug use, or the defendant wishes to remain. The jail

provides shelter, multiple meals per day, medical services.

Plaintiffs’ claims should be dismissed. Plaintiffs are asking court to intervene. Plaintiffs’ claims should also be dismissed. Judges are not the

creators of bail. The judges are immune from damages.

And so those two pages are the judges explaining why bail is okay, and I just thought that was just really disturbing for a judge to say, people

want healthcare. They want three meals a day, and that’s why bail is legitimate.

BETTS: And that’s just a sort of contrary to any idea that I think we should hold our freedom and due process and innocence until proven guilty.

MARTIN: In one way, we live in a cruel time where there is not a lot of sympathy, particularly at the highest levels for people who are

incarcerated. There’s a lot of demeaning language directed at people.

On the other hand, though, there’s an awareness of things that people weren’t talking about when you were 16, like the brain development of 16-

year-olds.

The fact that as you pointed out, 16 year olds can’t serve on jury. So how are they being judged by the jury of their peers? There’s even a movement

to allow 16 year olds to vote.

BETTS: Right.

MARTIN: As you are aware of so. So when you put it together, are you, you know, how do you see it? Are you encouraged by the present moment? Are you

discouraged by the present moment?

BETTS: I think the present moment is sort of complicated, right? Because in ways you know, first, the rhetoric sometimes doesn’t match the things

that people do in practice. So there’s some really positive things to look for — to look towards.

They’ve been raising the age for incarceration, really like all across the country. Where now most states aren’t really trying cases. Well, they still

have mechanisms to track you as adults, but it’s not that automatic, you’ll be tried as an adult, if you’re 16, like it was in New York for a long

time, like it was in Connecticut for a long time and North Carolina for a long time.

They also have more mechanisms to allow you to — when I got tried as an adult, it was automatic, and there was nothing that my lawyer could say, no

argument that he could present in front of the judge to say that Dwayne shouldn’t be tried as an adult for these reasons. Once the prosecutor made

the decision, there was no looking back.

And so we’ve had some change on those fronts. But I still think that most of the rhetoric has been to raise attention to the issue, but not really to

develop meaningful strategies and laws to change it.

Now, I feel confident, you know, Virginia — I was locked up in Virginia — the entire eight and a half years I spent in Virginia every year, we hoped

that parole will return. Little did we know that for those eight and a half years, there was probably no hope.

But this year, Virginia went blue, and it’s the first time in a generation it has gone blue, and there’s real hope and possibility that they’ll bring

parole back, and so we’re talking about bringing back measures that allow people to say, listen, I made a mistake, but I don’t think that I should

spend the rest of my life in prison.

MARTIN: Before we let you go, what would you say to people who say I just don’t — I don’t care. You know, people did something wrong. They should

just stay there, and they’re not a priority for me, for people who just say, I just — I don’t care. What do you say?

BETTS: I will say that, I’ve been like all across the country. And I’ve done events at universities all across the country and the thing that

always gives me hope is I’ll be in a room filled with white people, wondering why they invited me?

And I’ll just read my poems and answer the questions. And there will always be two or three people that come up to me and say, you know, my dad was

locked up my whole life. Oh, you know, my uncle wasn’t locked up, but he was abusing my aunt, and he was only then locked up about four.

So I think what happens is, I am convinced that I was in North Country, and it was a mass incarceration social justice conference put on by a church

there. Right? And, you know, this is rural white America, and they are putting on a conference to think about issues of mass incarceration,

basically in upstate New York.

And so what I would say to people is that this is not quite as capped a black American problem. This is an American problem. By percentage, we are

overly represented in the criminal justice system, but there’s more white people incarcerated than black people. Right?

And I think that to that person, I will say that once that really, we’re not talking about the other. We’re talking about our cousins, our uncles,

our aunts. We’re talking about the friends of our cousins, our uncles, and our aunts. I mean, this problem has gotten so enormous with more than, like

90 million people with a criminal record, that everybody has no more than three degrees of separation from somebody who has a criminal record.

And if they admit that to themselves, and they read “Felon” or a recent other literature, I think it becomes obvious, and it just doesn’t hurt us.

It makes us better to find ways to treat each other more justly.

MARTIN: Reginald Dwayne Betts. Thank you so much for talking with us.

BETTS: It was a pleasure. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: So poignant. And finally, leaders gathered in Davos have launched the One Trillion Trees Initiative to fight the climate crisis. But

children have a message, “Stop Talking Start Planting.” Plant for the Planet is a global movement where young people from 74 countries are once

again showing the adults how it’s done.

More than 13 billion trees have already been planted, and last year, they pledged to make that one trillion trees. So as we wait for massive carbon

emission cuts, trees are the only real carbon capture machines here on Earth.

AMANPOUR: That’s it for now. But join us tomorrow when we have the Oscar nominated actor David Strathairn on the program ahead of Holocaust Memorial

Day next week.

We’ll be discussing his one man show tracing the life of World War II hero, Jan Karski, the Polish courier who saw the horrors of the Jewish ghettos

firsthand and told the world.

Until then, you can always catch us online on our podcast and across social media. Thank you for watching and goodbye from New York.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END