Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, AUTHOR, “ELON MUSK”: And so, I thought, OK, he’s pushing things forward. But I also got to see that that can be kind of dark at

times.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

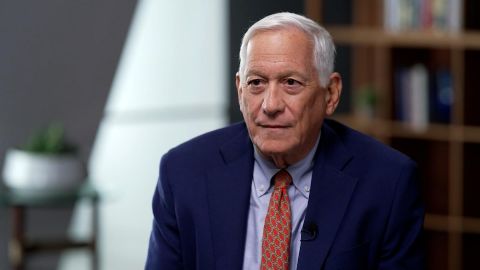

AMANPOUR: Biographer Walter Isaacson on the controversial Elon Musk. Our conversation about his spiraling influence as a billionaire entrepreneur.

Then —

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: One in every three with them around the world experience physical or sexual violence during her lifetime.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: — the never-ending scourge of gender-based violence and ways to tackle it.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SUSAN GLASSER, STAFF WRITER, THE NEW YORKER: The bottom line is, Joe Biden is already the oldest president ever to be an American president. Of

course, second oldest was Donald Trump.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The New Yorker, Susan Glasser on what she calls the dangerous reign of the octogenarians, but does age affect the ability to lead?

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York.

Elon Musk needs no introduction. The world’s richest person, he’s a divisive figure, a villain to some and a genius to others. He’s the

forefront electric car movement, space, travel, social media and now, artificial intelligence. Along with other tech heavyweights, the Tesla boss

joined a meeting with congressional leaders in Washington on Wednesday to discuss the risks and the opportunities of A.I.

Here’s Musk leaving the meeting.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ELON MUSK, CEO, TESLA AND SPACEX: I think so to go (INAUDIBLE). I think this meeting may go down in history as very important for the future of

civilization. The reason that I’ve been such (INAUDIBLE) for A.I. safety in advance of sort of anything terrible happening is that I think the

consequences of A.I. going wrong are severe. So, we have to be proactive rather than reactive.

There is some change that — above zero that A.I. will fill us all. I think it’s low but there’s some change. I think we should consider the fragility

of human civilization.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Human civilization indeed. And like many powerful billionaires, Musk also finds himself willing and able to effect policy, even war. Our

colleague, Walter Isaacson, spent two years shadowing him, and the result is a 670-page biography that is certainly making waves as we discussed here

in New York.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Walter Isaacson, welcome —

WALTER ISAACSON, AUTHOR, “ELON MUSK”: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: — to our program. So, here you are authoring yet another genius biographer.

ISAACSON: Indeed.

AMANPOUR: What is it about Elon Musk that really peaked your imagination for this?

ISAACSON: Well, when I first started, he was the only person able to get American astronauts into orbit ever since the space shuttle has been

decommissioned and he was doing more than anybody to bring us into the era of electric vehicles, to create batteries, to create solar roofs.

So, I thought he was doing these epic missions. Of course, in the middle, after a year or so of reporting, he decides to quietly start buying

Twitter. So, it became much more of a roller coaster ride. It also revealed both the drives that come in his head, but the demons that are sometimes

dark and sometimes he can channel into drives.

AMANPOUR: What did you go in thinking about him and what did you emerge?

ISAACSON: I thought at first that he was a technologist who had a really good feel for manufacturing, how to make factories. Also, that he was a

risk-taker. And then, in this country, in fact, in all of the West. We used to be more of a risk-taker, you know, everybody who came to the United

States came — whether the Mayflower across River Grand taking some risks. But now, we have more referees than we have risk-takers. You know, we have

more lawyers and regulators than we have innovators.

And so, I thought, OK, he’s push things forward. But I also got to see that that can be kind of dark at times, that it can break things. It can blow-up

rockets. And then, of course, it can really disrupt Twitter. So, it’s about — it’s a story about somebody who’s a tightly woven fabric of light and

dark strains.

AMANPOUR: And I wonder whether it’s — you know, you talk about referees, but one of the critics of — critique of Musk is that he is such a powerful

private wealthy individual that he can just walk around the world making policy, you know, replacing NASA, replacing the internet. Having a real

role in active war like in, you know, our internet generation in Ukraine.

I need to ask you because it’s in the news.

ISAACSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: How do you explain this discrepancy regarding the Starlink and activation over the Ukraine attempt told take the war to Crimea in the

early days? You said one thing in your book that he turned it off and he says another thing, and you’ve had to walk it back. How does that happen?

ISAACSON: Well, I’ve talked to him about that. That night, when it was happening in September, he said to me, hey, we disabled — we’re not

enabling this attack because it could start World War III. It was very apocalyptic. Says, we’re not going to let them use Starlink to do the sneak

attack there. And I made the mistake of thinking he meant that night he turned it off. And later he said, no, it had already been disabled but the

Ukrainians, all of the text messages are in the book, they’re amazing, were trying to get him to enable it. Because they did not know he had it

disabled.

And so, I made a mistake in thinking that the decision to disable it was made that night, it had been made before then. It’s called geofencing. But

still the main thing was he got to decide that night, do the Ukrainians get to do this attack or not do this attack. So, it doesn’t affect that. And it

doesn’t even affect the larger question is, how come he got to decide? Why is a private citizen deciding whether or not —

AMANPOUR: Well, that was my question.

ISAACSON: — the Ukrainians can do it?

AMANPOUR: How is that even possible? Does that trouble you about somebody like Musk?

ISAACSON: Well, I think it even troubled Musk after a while because he talks to General Mark Milley of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, talks to Jake

Sullivan, the national security adviser, and they work out a deal where SpaceX, Musk’s company, will sell some of these satellites to the U.S.

military and the U.S.military gets to decide. And that’s really the way it should be.

But there’s a larger question here, which is, how come, when the Russians attacked Ukraine, all of the U.S. military satellites via sat, everybody

else doing communications gets knocked out, and the only person in the world who has a communication system that can work is Musk? And it’s still

the case. And part of the reason is we don’t build these things well as we should.

AMANPOUR: So, that’s a lesson for American technology and business and science.

ISAACSON: Absolutely. NASA, the defense agencies, they should not have to depend on one company. Do you know that all communications, big, big

communication satellite, even for our intelligence agencies that have to go into high earth orbit, they’re done by SpaceX? They launch it. Because NASA

and Boeing have become somewhat sporadic.

AMANPOUR: And what about, even this week, as he meets with Kim Jong Un, President Putin praised Musk, great American businessman, a great citizen

of the world, does that bother Musk this, you know, act of imperialistic aggression, as it’s being described, you know, he’s talking to the

aggressors and maybe getting a little bit of context for his Starlink availability from what the Russians say, this idea of starting World War

III? Is that really a concern right now?

ISAACSON: Well, Musk have somewhat of an apocalyptic vision, as he often does, of what can happen. And he talked to the Russian ambassador. The

thing though to remember is when Russia invades Ukraine, that night, Ukraine has no way to communicate with its troops, via sat, all of the

other satellites out. The only other way to communicate would be Starlink and Musk rushes hundreds and then thousands of Starlink terminals over

there for free, as a donation.

So, he’s supporting the Ukrainians. But at a certain point, he says to me, how did I get into this war? You know, I didn’t mean for this to be useful

offensive purposes.

AMANPOUR: Here’s a comparison that you make between Musk and Jobs. Let me read it. Like Steve Jobs, he genuinely did not care if he offended or

intimidated the people he worked with, as long as he drove them to accomplish feats they thought were impossible. It is not your job to make

people on your team love you, he said at a SpaceX executive session years later. In fact, it’s counterproductive.

OK. So, I get that. But the sort of companion question about that is there was a discriminatory sort of working conditions at the Tesla factory,

right, in Freemont, it went to court. If Elon says he knew so much about all the working conditions wherever his factory flaws were, how did he not

know about the alleged racist language, behavior towards minorities? Is it fair to say his focus was only on that quote, like production, production,

production, and not on the people and the quality of the working environment?

ISAACSON: Absolutely. I mean, Musk focuses so much on production, getting things done fast, and he doesn’t focus on having a nurturing or careful or

nice working environment. That was true at Tesla. That’s why he got sued. That was true at Twitter when he takes it over. He says, everybody is

talking about psychological safety and sweetness, I’m talking about hard- core all-in intensity.

So, that lack of empathy we talked about, that extends to the fact that, no, I want to really tough workplace, and he’s not all that sensitive,

which he should be. I mean, this is one of the down sides.

AMANPOUR: Are geniuses, in your experience, those who you’ve written about, do they all have that bit of DNA?

ISAACSON: That’s a really great question. I think not all of them. But it is true that when you look at any of the great disruptors or innovators,

whether they’ve been the ones I’ve written about, you know, Steve Jobs or Elon Musk, or people like Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, the ones you know,

they can be disruptive, which means sometimes pushing way too hard.

However, I’ve written about other people, Jennifer Doudna, who is one of the greatest innovators of our time. She creates CRISPR for the gene-

editing technology. She’s nurturing. She’s nice.

AMANPOUR: She’s a woman.

ISAACSON: She’s wonderful. She’s a woman. And Ben Franklin, nurturing, nice, wonderful, brings people together. Biographies aren’t sort of how to

book, it’s a, here’s the way you’re supposed to be. They tell you about a particular person.

AMANPOUR: Ted Turner who is the founder obviously of CNN —

ISAACSON: Correct.

AMANPOUR: — was a phenomenal and is a phenomenal genius, but also had amazing empathy and do the right thing. So, there are many people who do

the right thing.

ISAACSON: Precisely. But, you know, you and I both worked for Ted Turner. There was a craziness to him too, right?

AMANPOUR: Well, that’s different than abusive.

ISAACSON: Right, right. Now — and it’s — you know, definitely, he was never abusive.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ISAACSON: But there are certain drives and demons that sometimes very successful people have. And they channel those demons in different ways and

—

AMANPOUR: So, this gets to the heart of Musk’s childhood, his chips on his shoulders, his demons, his dark. So, Kara Swisher, of course, renowned tech

journalist, interviewed you in March about this and she wrote on Twitter, X, whatever that means, the review of the biography. She says, my mini

review of the Musk bio, sad and smart son slowly morphs into mentally abusive father he abhors except with rockets, cars and more money. Often

right, something wrong, petty jerk always. Might be crazy in a good, but a bad way. Pile o’ babies. Not Steve Jobs. You’re Welcome.

Your response?

ISAACSON: I love —

AMANPOUR: Accurate?

ISAACSON: Yes. Yes. I think almost all those things are accurate. You know, and when I first started this book, Elon Musk’s mother, Maye, says to me,

the danger for Elon is that he becomes his father. And indeed, he had this psychologically rough father who would make Elon stand in front of him as

he berated him more than an hour, would go from light to dark moods. Well, that happens too with Elon Musk, and that sometimes the way he treats

people. You know, he gets stuff done, but that doesn’t excuse the behavior sometimes.

AMANPOUR: And he — you know, there’s obviously, in your book and elsewhere, he’s talked about being terribly bullied as a kid growing up in

South Africa.

ISAACSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Is that separate from his father’s bullying and abuse?

ISAACSON: Yes and no. I mean, he gets bullied on the playground at school in such a way that they beat him in the face so that he has to go to the

hospital. He’s almost unrecognizable. But when he comes home from the hospital, his father makes him stand there and his father takes the side of

the person who beat him up and berates Elon Musk.

AMANPOUR: Takes the side of the person who beat him up?

ISAACSON: Beat up Elon and says —

AMANPOUR: His own son?

ISAACSON: Yes. His — over his own son and said, you’re stupid. And, you know, this leaves scars that are psychological.

AMANPOUR: You did tell “New York” magazine that he has an epic superhero savior complex.

ISAACSON: Ever since he was a kid, he read the comic books and he said, it’s weird. These comic book heroes, they’re all trying to save the planet

and they’re wearing their underpants on the outside. They look ridiculous, but they are trying to save the planet.

And he, as a child, he’d sit there in the corner of the bookstore for hours, reading these comics and he’s developed a role, which is, if Ukraine

gets invaded by Russia, I’m going to send stuff in. I’m going to come help. And there’s, you know, a cave in Thailand has kids stuck in. I’m going to

send in a submarine to help. He likes this notion of helping humanity. In fact, he has more empathy for humanity in general than he often has for the

20 people around him.

AMANPOUR: And even the pile o’ babies, as Kara Swisher point it, he has a lot of kids.

ISAACSON: Right.

AMANPOUR: Does he own them all in terms of, you know, acknowledge them all? Where does this come from?

ISAACSON: Well, he believes — I mean —

AMANPOUR: It’s like 10 or so, right?

ISAACSON: Yes. I’ll give you the —

AMANPOUR: With several different women?

ISAACSON: Yes. I will give you the grand thoughts that he has about it, which is, you know, human consciousness, human civilization is a great

thing. And in order to keep it alive, we all have to have lots of children. He actually believes that.

AMANPOUR: But that’s weird in this world, isn’t it, with the climate crisis, with the existential crisis, with the overpopulation.

ISAACSON: Yes. And I think he — well, I think he would say, no, the declining birth rates are the problem.

AMANPOUR: So — OK. So, as we talk, it’s very clear that your mandate as a biography is more of an explainer, a fly on the wall, you know, the people

who you’ve covered have given you incredible access and we get an amazing insight because of it.

Pushback has been that you don’t make judgments, you may not pushback against them enough or as others do, you may not do the sort of deep dive

that a — you know, that a Robert Caro has done for years, decades producing the very deep biographies of like Lyndon Johnson. What do you say

to that?

ISAACSON: Well, I’ll plead guilty, which is I’m a storyteller. I’m there reporting it, I’m giving you facts, I’m giving you a narrative, I think I’m

giving you a pretty relating (ph) tale too. But I think every anecdote in that book is revelatory. Everything tells you something about how Musk

works, good and for bad.

And I will cop a plea that I tried to tell the stories and let the reader come to some of the deep judgments, because I think, when I grew up, they

used to say there are two types of people, preachers and storytellers, I think the world got a few too many preachers these days and maybe just

telling the story, honestly straight, sometimes you’ll be appalled by the stories, sometimes you’ll be amazed by it, but you get to watch that

trajectory with me telling you the story as I saw it as objectively as possible.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk about Twitter, which you alluded to at the beginning. You know, this massive global town square that he, you know,

then bought and, you know, beset by controversy and personal dynamic from the beginning. I mean, for whatever reason he changed it to X, I can’t even

fathom. But do you understand that?

ISAACSON: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And also, coupled with that, the critique is that he has morphed Twitter from a more communal space to a space where hate speech is

unregulated, where the conflicts and divisions and discords and the lack of reigning that in, that previous owners, I guess, tried and were forced to

do, is now, you know, just full blown. How can that be good?

ISAACSON: I think 20 years ago, he had an idea what he called x.com, that becomes PayPal, which he thought would be bigger, it would be a financial

services ap and social media together where people could post content, make, you know, money by creating things. And now, he’s trying to recreate

that with what was Twitter. And that’s why he’s change the name to X.

And in doing so, just as you said, he turned it from being a pleasant place, where people like you and me get anointed with blue checkmarks and

have sweet little conversations among the media —

AMANPOUR: Which are —

ISAACSON: — with all kind of love —

AMANPOUR: — all cancelled conversations.

ISAACSON: Yes, yes.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ISAACSON: And he wants it to be more hardcore, just like he wants all of his work environment. So, he wants a broader range of speech there. And

sometimes when you do that, you get some pretty fringe characters.

And what’s even worse is when those fringe characters get amplified a bit, when he engages with them and things. So, it’s become a much more

contentious place, but that — it’s also a place a lot more people are using it too. I mean, it’s not just this sweet playground that it was back

when you and I are doing it.

AMANPOUR: Is it financially viable for him and do you think he’ll keep it?

ISAACSON: I think that eventually he will be able to have subscriptions and payments and transfers of money that will be the main source of revenue,

because it will not be financially viable, I don’t think, as an advertising medium because it’s just so, as you said, controversial for advertisers.

AMANPOUR: And so, this is important, obviously, as it is always is, the attack on the Anti-Defamation League. A number of notorious anti-Semitic

accounts posted under the hashtag, ban the ADL. And, you know, Musk blamed, you know, ADL for most of X’s — for the X loss in revenue and called the

ADL the biggest generator of anti-Semitism on X. Threatened to sue it, et cetera. And David French of “The New York Times” says his claims of the

ADL’s immense powers tapped into classic anti-Semitic tropes. A, did you bring that up with him? And B, does he — is he — is that who he is?

ISAACSON: Yes. I think he’s totally wrong. I think the problems that X is having now is not because of the ADL trying to stop him. It’s because it’s

an environment that’s so controversial and so messy that advertising brands don’t feel comfortable being on it. It’s just that.

If you talk to Jonathan Greenblatt of the ADL, he’ll say, Musk is not anti- Semitic, and, you know, he defends him in some ways. But what you have is an environment where a lot of French players are getting amplified and

advertisers don’t want to be there understandably.

AMANPOUR: All right. Walter Isaacson, thank you very much.

ISAACSON: Thank you very much.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And next, we turn to the persistent plague of gender-based violence. The numbers are devastating. Every day in Mexico, at least 10

women are killed. And here in the United States, femicide has increased by almost 25 percent over the past eight years. Today, the Ford Foundation is

bringing together some of the world’s leading experts on this subject to discuss the urgent need for solutions.

The Free Future 2023 forum is taking place here in New York. And I’m joined now by two of the speakers, Tarana Burke, founder of the MeToo Movement,

and Mariam Mangera, who is a project coordinator at the National Shelter Movement in South Africa. Ladies, welcome to the program.

Can I start with you, Tarana Burke, because MeToo sort of exploded into our consciousness almost exactly six years ago? And I’m wondering why you think

it’s still, you know, not done enough to quell this side of the gender equation?

TARANA BURKE, FOUNDER, METOO MOVEMENT: Well, first, thank you for having us. And I think it’s because we don’t see sexual violence as social justice

issue. I think largely people still see — associate MeToo in pop culture as a gender war, as he said she said, and we don’t really look, even though

the statistics show that sexual violence happens every 68 seconds, that one in 10 children will be affected by sexual violence before they turn 18. We

do not see this as a public health crisis or a social justice issue.

And as long as we don’t take it seriously in that regard, we will still continue to see the problem grow the way it is, exponentially.

AMANPOUR: And I just want to ask you to please explain to me this, I mean, horrendous figure of 25 percent higher femicide in the United States. Do

you know — do you accept that figure? And is it because it’s happening more? Is it because more people are reporting who might not have done

before?

BURKE: I think it’s a combination of both. You have to also realize that we have seen a rise over the last decade in toxic masculinity and in, you

know, things like — you know, the president that we’ve just had. We’ve seen a rise in the change, in, you know, conversations on the internet,

we’ve seen all of the mass shootings that we’ve had across the United States, something like 60 or 70 percent of mass shootings have — the

shooters have a history of domestic or sexual violence, those things are all connected.

And so, when we don’t talk about sexual violence and connection to things like gun violence and violence in general, we lose sight of the fact that

things like femicide are growing. And that’s lost in these conversations because we never talk about sexual violence as a social justice issue.

AMANPOUR: And I wonder, if I could turn to you, Mariam Mangera, because is it a social justice issue in your country where we’ve reported many, many

times on the terrible epidemic of sexual violence against women. I mean, I interviewed, for instance, Graca Machel, the first lady of South Africa,

her daughter, Josina, in 2015 where she described and, of course, it’s well-known to you all how she had been beaten up multiple times in the head

by a former partner to the extent that she lost sight in one of her eyes. This is what she told me this back then.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOSINA MACHEL, DAUGHTER OF GRACA MACHEL AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE SURVIVOR: Thousands of women wake up every day as if they were soldiers. We never

know how many of us will be beaten, how many will be raped, how many would be killed.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I mean, it’s really stark the way she puts it. Is there any improvement in South Africa since that time?

MARIAM MANGERA, PROJECT COORDINATOR, THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT OF SOUTH AFRICA: Good afternoon, Christiane. Thank you for having me. So, the stats have

actually been going down over the last quarter. However, over the past few years, they have been rising. I think the reason that the stats reduced

over the last quarter is because of nonreporting.

If we look at the way sexual violence has been, as you put it, over the last five years alone, you know, the South African police department had

said that in 2016 we were looking at only one in 23 cases of being reported. But now, we are looking at one in 36 only being reported. And the

problem is that 40 percent of all sexual violence that is reported is girls under the age of 18. And 15 percent are actually girls under the age of 12.

AMANPOUR: Wow.

MANGERA: So, the problem is getting worse, but it’s a cultural mindset that actually prevents reporting. And so, we don’t actually have a very clear

picture. And if we look at the one in 36 being reported, we are actually looking at over 2 million cases of rape not actually being reported.

AMANPOUR: Wow. You know what, that’s just staggering figures. And so, I want to ask you about the reporting phenomenon, both of you actually, but

first staying with you, Mariam. Those who do report, are they then taken seriously, accountability happens, investigation happens, or as we hear too

often, are they then revictimized a second time?

MANGERA: Yes. So, that is a very big problem. Victims of sexual violence or any sort of violence are actually revictimized in our justice system. We

have a very, very big problem where we have people working in the justice cluster that haven’t actually been trained how to actually approach victims

of sexual violence, whether it’s the prosecutors in shaming clients, whether it’s the police in taking statements, social workers in victim

blaming on what a victim was wearing.

But even as recent at 2016, we had a judge in South Africa that had been on Twitter talking about black men raping for fun or finding pleasure in it.

So, you know, the old racist apartheid mindset is still being carried through even into the justice system, and that is hindering access for

women of color and black women in particular.

AMANPOUR: And, Tarana Burke, in the United States, is that the same? First, the idea of anybody reporting it being, you know, taken seriously or

otherwise?

BURKE: Absolutely. There’s always been an issue with reporting in the United States, with survivors generally. I think because there is so much

shame associated with sexual violence, and it’s always been an issue with reporting, particularly in communities of color.

There is a stigma attached to talking about it. And in the black community, in particular, there’s a notion of protecting our men because of the way

that sexual violence has been weaponized against black men historical, black women are inclined to want to protect black men. So, there is a

history of not reporting inside of the black community with black women.

In other communities of color, also, you know, for instance, in immigrant communities, there’s a history of not reporting because they don’t want to

have interactions with law enforcement that might lead to their families maybe being deported. So, there are different reasons why there’s not

reporting in communities of color. But either way, not reporting is rampant with survivors of sexual violence, and it’s a problem.

AMANPOUR: In South Africa, Mariam, the black majority, they are the majority. And I’m wondering whether there is an intersectionality? Does

race play a part in this crisis? You touched on it a little bit, but does it specifically play a part in this crisis?

MANGERA: So, when we’re talking about violence and gender-based violence, obviously, it is intersectional violence, it is faced by all women. And

historically, black women and women of color did not have access to justice systems.

And, you know, when we speak about rape, it was white women that were raped by black men that actually found access to justice. However, the laws

itself back then did not see women equally, because as horrendous as apartheid was in terms of racial inequalities there was also gender

inequality. Women didn’t have rights under apartheid. We didn’t have a Domestic Violence Act until 1998, which was four years after the end of

apartheid.

But today, because the population of South Africa is 90 percent black, we tend to see the stats showing that more black women are affected. However,

there is no difference in who is affected, everybody is affected at the same rate, it’s just that because of the geographical and the racial

demographics of the country that we actually see more black women reporting.

AMANPOUR: Can I turn to solutions? Because forum that you’re attending and speaking at is designed not just to look the past but to go forward. So,

Tarana Burke, you know, in the United States, for instance, are there solutions? Have you identified further what is driving this epidemic and

what are the most important solutions to it that you could list?

BURKE: Well, first of all, when we talk about solutions there’s no single solution to the problem of sexual violence. It’s going to take multiple

interventions. When we look at how we’ve solved other issues in this country, it’s always taken multiple interventions. So, it’s going to take

legal interventions, political interventions, medical interventions, narrative interventions.

Part of what has to happen, a major thing that has to happen is a culture shift in this country. It’s against the law in all 50 states to commit acts

of sexual violence. But the problem happens when people commit those acts, what does law enforcement do? We already know that cost resolutions don’t

work, right, especially when sexual violence is happening inside of law enforcement. We don’t look at the kind of — the egregious acts of sexual

violence that happens inside our prison system.

Sexual violence is the second most reported act against police and law enforcement in this country. So, we know that cost resolutions are not the

way. So, we have to look collectively at multiple interventions, starting with narrative. We have to shift the way people think about sexual violence

in this country. We have to shift the way people talk about it. And we have — and part of that is, again, looking at this as not an individual act,

right, we — that’s between the two people, just the person who committed the act and the person who is surviving the act, but it’s a — it is about

safety. We have to reimagine what safety looks like.

So, if one person in your community has survived — has dealt with sexual violence, nobody in that community is safe. And we all — when — just like

when gun violence happens in your community. If one person survives gun violence in your community, everybody in that community wants to think

about how we can keep everybody safe.

So, we have to shift how we think about sexual violence in this country before anything else can happen. That’s one of the solutions, it’s a major

solution. We need more research, we need more medical research, Political, all of those things has to happen collectively at the same time. There’s no

singular solution.

AMANPOUR: And resources as well, because we read that gender-based violence, for instance, the stats show that, according to a report in 2019,

funding for these programs amount to only 12 percent of a country’s humanitarian aid. And it’s not just about —

BURKE: If —

AMANPOUR: — you know, how much, but who gets it.

BURKE: Let me just say this, sexual violence is one of the most under resourced issues in the world. And that’s everywhere. It’s under resourced

for nonprofit organizations, it’s under resourced in law enforcement, it is under resourced everywhere. People think that money moved to the issue of

sexual violence after MeToo went viral, and it did not. We are severely under resourced globally. And I’m sure you can speak to that.

AMANPOUR: Well, Mariam, I’m sure that is the case, as Tarana says, everywhere, including South Africa, is it?

MANGERA: Absolutely. You know, in 2019, the president did announce that he was reallocating 1.6 billion towards gender-based violence emergency

response. But, you know, at the time, we didn’t even find out where the money was being spent, if it was being spent. We worked on an emergency

response plan to actually tell government where the money should go in order to assist. But we don’t even have that kind of input any longer.

So, I think that the biggest issue around resourcing is not just lip service, it’s actually accountability that goes with it. We can say that

we’re giving hundred million dollars towards GBV. But at the end of the day, who is the one that actually holds government accountable? Who is the

one that holds foreign donors accountable?

Because a lot of time what happens is funding that comes from overseas, especially into South Africa, is actually — the donor says to you, where

it is that you need to spend, how to spend, and we don’t actually have the autonomy to actually address gender-based violence in the way that we see

it needing for resourcing, because we are so reliant on external funding.

AMANPOUR: And can I ask you both, because stats seemed to be showing transgender people are far likelier to be victims of violence of this kind

of violence than cisgender people. Is this — it is — is this reaching an emergency situation? Has it all always been like that or not, or are we

just sort of, you know, seeing it now?

BURKE: Absolutely. It is — sexual violence is a public health crisis, full stop. In the transgender and gender expansive community, we’re now seeing

it for what it is because they are now starting to collect data and put out data, but it has always been at a fever pitch in that community. And I’m

glad we now have numbers to attach so the people can actually see what’s going on inside of the gender expansive community.

But, yes, it has always been that way. They are endangered around — when it comes to sexual violence both inside in the world and inside of law —

and when they’re incarcerated. But yes, transgender folks are definitely in danger when it comes to sexual violence.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you both, finally —

MANGERA: And all forms of violence.

BURKE: And all forms of violence. Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: Yes. — what you hope to persuade men to do to help this situation. And particularly, whether that is also about what you

identified, Tarana, as, I think, empathy theory?

BURKE: Well, it’s empowerment to empathy. But let me say first that men’s first role in this movement is as survivors. And we should — I don’t want

to separate them as just the solution to sexual violence. We have to acknowledge that this is a movement for survivors, not just for women.

Women are largely the victims of sexual violence, but so are men and so are gender expansive people. So, men’s very first role in the movement are as

survivors. We have to recognize that this is about institutions and this is about how sexual violence has been institutionalized around the world.

And so, all of our role is to rethink how we understand sexual violence, the breadth and depth of it and how it’s ingrained in our culture and our

society. We need men, we need women, we need all of us to dismantle patriarchy and sexism so that we can move away from our understanding and

our socialization around sexual violence.

AMANPOUR: Well, thank you both for telling us — you know, updating us on this and taking part in this important forum. Tarana Burke, Mariam Mangera,

thank you very much indeed.