Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Jamil Jivani grew up in an immigrant Canadian neighborhood feeling isolated and estranged from his own dad. He was on the road to a life of crime and gang violence, and yet, moments away from buying a gun, he decided to turn his life around, eventually ending up at Yale Law School. He is now devoting his life to helping young men at risk. And he spoke on Michel Martin about his first book, “Why Young Men Rage: Race and the Crisis of Identity.”

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN, PBS HOST: Jamil Jivani, thank you so much for talking with us.

JIVANI: Thank you for having me.

MARTIN: What is it that you’re doing with this book? What is it that you’re trying to do with this book?

JIVANI: I think we’re in this moment right now, where masculinity is being redefined. You know, the economy is changing where the jobs that men used to count on, especially working class men are starting to gradually disappear due to automation. We now share, thankfully, the labor market with women and in many cases, women are outperforming us academically and professionally. And so I think men are trying to figure out what does that mean to be a man? Like if the old kind of advantages that it used to have. It’s the old definition of masculinity as it relates to my family or my partner changing? And what does it mean to be a man in the 21st Century? And I see, I see a lot of boys and young men going online, going to their peer group, going to the streets looking for answers to these questions. And I think they’re finding, in many cases, not great answers. So what I hope to do with the book is to not just communicate, I hope, better answers to those boys, by showing these are the people, these violent movements that are out here trying to answer that question in negative ways, but also to hopefully help parents and people who work with youth to think about how they might offer an affirmative, proactive answer to that question.

MARTIN: Tell me a little bit about when you were growing up. I mean, you talk a lot in the book about how important it was to you to be cool and to kind of fit in. I mean, that’s not unusual. I mean, like, it’s the rare teenager who doesn’t struggle at one point with like, “Where do I fit in?” And like, what did that look like for you?

JIVANI: Yes, well, so myself, and a lot of my peer group also didn’t have fathers around. We didn’t have older males in our community very much. We were in a newly urbanized suburb that was specifically urbanized by immigrant communities. And so there wasn’t a lot of tradition around us. This is a young community. What that meant is that we would leave our mom’s houses every day on our way to school looking for the father figures that we didn’t have at home and we would find those in the CDs that we listened to or on the music videos, or — and pop culture really is where we found the male role models that we were wishing we had in our house or in our neighborhood. So for a lot of America, that is just entertainment. They can see the distinction between, “Hey, this is a rapper or this is an actor. Maybe they make a good movie, maybe it’s compelling.” But I leave it at that. For us, because those were not just entertainers. I mean, they were like clerics. They were sources of wisdom and inspiration. They were people who thought we were supposed to model ourselves after. And so we took what was entertainment to some people, and we took it to heart, we took it very seriously and that gangster subculture is something that we were drawn to because of that.

MARTIN: Talk to me a little bit about school. You just didn’t put much effort into it, because it wasn’t cool or you just thought it was boring, or why is that?

JIVANI: That’s definitely the case. I mean, when all your idols are people who are these outlaw, you know, anti-authority figures, right? It’s hard to think that the, you know, kind of boring, monotonous life of doing your homework and writing tests is exciting or interesting. And I think that was hard for me to say like, I should be putting my time into things that are — that don’t offer immediate gratification, or even more specifically, where I’m not going to feel admired or respected by my peer group if I do these things. Whereas if I’m out in the cafeteria, punching someone in the face, people are going to say, “Oh, you’re cool, you’re tough.” You know, so there’s that kind of affirmation that I didn’t have with school. But I also felt to be honest that, our society was just rigged against people like me. I didn’t think that I had, like, there was no meritocracy in my mind. So what’s the point of working at school, if you think people don’t want you to be successful? They’re not going to give you a job. When you go to the mall, you’re followed around by security guards. It all added up to this feeling of I’m not just destined for success here. So why bother.

MARTIN: So that you fail this literacy test? And that was a pivot point for you. I mean, you talked about the fact that it made you feel like garbage, like they actually thought that you couldn’t read and you talk about the sort of the duality of that. On the one hand, it made you feel horrible. On the other hand, it was a motivator for you. Why was it a motivator for you?

JIVANI: Part of the motivation for me was that it just sent me a bit over the edge, like I doubled down on feeling rejected from the school system. I doubled down on feeling excluded from the possibility of success. I came close to buying a gun and participating in all sorts of things that you know — where I was one very small decision away from potentially ruining my life and entering a system that is very unforgiving and unjustly so to young men. So because I had realized I didn’t want to go down that road. I’m not going to be a gangster. I don’t want to buy the gun. That life isn’t cut out for — or I’m not cut out for that life. What do I do now? And it turns out when you don’t have anyone to smoke with and drink with and skip classes with and share gangster fairy tales with, going to school becomes a lot easier. And then going to class and you just start to re-socialize yourself gradually because you have a new peer group around you. And that’s ultimately what failing that literacy test kind of pushed me so far away that I kind of came back in a bit of a boomerang effect, I think.

MARTIN: So I’m going to fast forward a lot.

JIVANI: Yes.

MARTIN: So you go from failing student who fails a literacy test, doesn’t care to college. You go to Yale Law School, and then what happens? What did you decide to do with all of that?

JIVANI: My experience at Yale was this abrupt and dramatic confrontation with privilege. And this idea that you go from being someone who feels like you’re scratching and clawing just to get a chance to prove yourself to all of a sudden now feeling like the world is in front of you, like you can have all these job options, and you’re empowered, and you’re — now everyone who — these institutions that used to say you couldn’t even read it or write, now, they’re telling you, you’re a genius. And it’s just like — it was this very overwhelming feeling that I wasn’t sure what to do with. And part of how I reconciled with it was I decided that I was not going to just be a student at Yale, I was going to be someone who took it upon myself to share that privilege with as many people as possible. I wanted to feel like the empowerment I received, that affirmation, that positivity of “you’re smart, you’re capable.” There’s a world out there that you can be successful in and a place where you can belong. I wanted to evangelize that message.

MARTIN: One of the things about this book that’s interesting is that you – – we’ve spent a lot of time so far in your personal story. And you kind of marry that personal story to what a lot of people are talking about around the world — violent extremist movements all over the world that young men are attracted to. Why are so many young men, in your view, attracted to these violent extremist movements? You know, looking at it from the outside? You think that’s ridiculous? Why would you want to do that? What have you come up with?

JIVANI: Yes, I try in the book to connect the dots between, you know, gang violence, jihadist terrorism and white supremacist violence, because I think that too often, minority groups are pathologized as owning these problems uniquely. And I think that when we connect the dots, we show that this just kind of transcends our racial or cultural differences. I mean, there’s something about violent movements that appeal to young men in various different circumstances. When I first started thinking about this, I had been, so, used to thinking about this as a mostly economic problem, right, that poverty explains this. And the more I dug into it, the more I tried to understand the complexity of the problem of why middle class kids were the ones in many cases leaving to go join ISIS in Syria, or middle class kids were at that Charlottesville rally two years ago. I think what I found is that these movements are experts at reaching young men on a few different frequencies. So, one is, they expertly echo the anger that a lot of young men feel.

Now teenage angst or the angst of a young person, something we all can relate to, I think. I mean, most of us when we look back at pictures of ourselves when we were 16, we wonder who that person was, right? But what these movements do really well is they send a message of the reason you feel that way is because the world around you is to blame. Not that it’s normal. That it’s something you need to work through, or that there are loving adults who might help you cope with those feelings. But rather, that you should be primarily responding to that with more anger and more resentment, and you should hate people, whether it’s hate the west or hate your rival neighborhood, hate immigrants and newcomers. They’re picking a target and they’re making you personalize your anger that you feel inside and they do that very well. The other thing they do is they offer brotherhood and camaraderie. They’re saying, “We want you to be part of us. We want you to be one of us. We want to walk beside you in life,” and to an isolated, lonely young man, that can be a very appealing message and a lot of the guys who joined these movements are people who are seeking mentorship from older men. They’re seeking friendship, they’re seeking camaraderie and these movements especially with the way they use the internet are able to really pinpoint where you might find that isolated young man who’s in need of a friend.

MARTIN: A number of people who’ve been studying terrorism for quite some time have made that connection. What do you think you’ve added to this that’s new?

JIVANI: What I hope I’ve added is that I — we have an impulse to want to see the solution to these problems as equally dramatic as the problem itself. So what I mean by that is, we recognize these are global issues, they’re international issues, they’re threatening the national security of many nations across the world. They are threatening the safety of neighborhoods across America as well. And yet, we are hoping for some sort of national or international response, right, that there’s some sort of magic idea. All of these countries could get together and we can fix these problems. I think a lot of it, though, is very local. And that’s what I try to bring to the analysis is to say, well, the reason why a young man joins these groups is not because he is sitting around thinking about foreign policy. He is not sitting around thinking about the international economy and globalization.

A lot of it comes from the pain he feels inside. It’s he lost his mom or his father is not around, or he had a negative experience at school, or he’s in a neighborhood where the police aren’t keeping people safe. Right? There’s things going on, on the grassroots level that make these groups appealing. And I try to bring that and that’s partly why I tell my own stories, because I talk about the personal lives of a lot of young men, and I felt it was important to, you know, reciprocate that honesty and that vulnerability by saying, yes, that that feeling of isolation that these groups are preying on, I felt that. I know what that’s like to feel hopeless. And that is what I bring to the table, I think is the local personal understanding of what’s going on in the lives of young men.

MARTIN: What are some specific things that you would like to see people doing to address this global malaise, I would call it among boys — some boys and men that has implications for everybody?

JIVANI: Well, one of the things that I advocate for a lot, especially with parents, or teachers, or people working with young people, and young men in particular, is bridging the gap between online and in person communication. So what I mean by that is, you know, we’re seeing more and more young people spending all their time on their phone, on their iPad, they are thinking about the world through Instagram, and through Twitter and through Facebook. And yet, they are not speaking to adults about what they’re seeing or what they’re saying.

And I think that what that creates is for these, especially these isolated young men who are most vulnerable to being reached, through those platforms by a violent group, I think that we need adults who are asking those questions. So even simple practices, as you know, every day or every few days talking about, “Hey, this is what I saw online, what did you see?” Like, “What are you reading? What are you — who are you following?” I think that’s something that we can do every day in our own households at our kitchen tables that would make a really big difference in the lives of more men. I think the other thing that I push for a lot is thinking about how we make public institutions more flexible. So if you’re thinking about, you know, a police department or school system, and you’re saying, “Well, how do they adapt to the needs of their community?” Too often, we have very rigid public institutions where reform takes years and years and years. And in that time, you could lose a whole generation to a negative influence that’s kind of set root in a neighborhood.

So what I push for a lot, for example, is certain charter school models that I think are flexible and understand what people need, forms of community policing that are more about listening than about telling people what they need. I know, those are not, you know, groundbreaking ideas, but I think seeing them as a starting point for stronger local community institutions, I think that’s really important.

MARTIN: Some of the Civil Rights activists in this country, I think, maybe it was Jesse Jackson who used to say that African-Americans are the canaries in the coal mine here, you know, that what affects black people first will affect white people later. I mean, could it be that the kinds of things you’re talking about, like diseases of despair, for example, or that, you know, the imbalance of performance of boys and girls in the classroom, it affected black people first, so therefore, people didn’t care? They didn’t care until it started affecting white people. Could it be that?

JIVANI: Oh, I think that’s absolutely true. I mean, no, no doubt about it. I mean, the idea that, you know — I’m reading this book about young men and drawing attention to the experiences of young men, but we know that thousands of the young men who passed away in this country every year are black boys whose lives are being lost to gun violence and gangs and all sorts of chaos. And part of why I fight so hard for that to be included in this conversation about radicalization and extremism is because it’s easy to forget that the first group of boys that we were losing to these anti- social ideologies in this decade were the black boys and now we see it with jihadists and we’ve seen it with these white supremacists getting more and more attention. But I don’t want that to crowd out the reality that we’ve allowed a very particular group of boys in America to shoulder a struggle for a very long time and not taking it nearly as seriously as we should. And we’ve written them off to — we built a justice system that made it that a lot of them never had a second chance. And we are more inclined to offer, I think, a second chance to a lot of other people, and that’s a real problem.

MARTIN: And what about countries where people are attracted to these jihadists sort of movements? I mean, do you find the same — do you find the same thing?

JIVANI: Absolutely. Some of the studies that I’ve looked at, for example, show that among first generation immigrants to Europe, you find a gender disparity where men are more encouraged to study and to earn a living and women are discouraged. In one generation that flips where you start to see in low income neighborhoods, women start to outperform men in the second generation of these families. And I think that’s because when it comes to the traps that are out there for a young man who doesn’t have a lot of money, the higher rates of interaction with police. They’ll hire — how much easier it is to get involved in crime. The allure of earning money illegally. When you see those traps, right, it starts to shift how young men are experiencing their society. They might go from in one generation, being the ones their family expects to make money and go to school, to all of a sudden their family thinking, well, now we need to take care of you because you’ve made all these mistakes.

MARTIN: Could you tell us a story of one of the young men that you work with who you either think you were able to have an impact on or who perhaps had an impact on you.

JIVANI: When I started the research for the book, and I wound up in Belgium, I went to this youth program that was designed to help young people who had dropped out of school, find a job. And they had all these different programs for construction workers, for fast food workers, for retail, and I went to one that was for housekeeping and it was all women there except for one guy. You know, he was probably the same age as me. He was a young Moroccan man who grew up in Brussels. And so I went over to him and I just asked him, “Why are you in this room? Like it’s you and a bunch women? Like, do you feel comfortable here?” And he said to me that he had just gotten out of prison and right before he got locked up, he had a daughter who he missed the first year of her life because he was inside. And he came out and said, “I need to be able to look after my family. And if I can get a job cleaning hotel rooms, and that’s the way I’m going to do it, then that’s enough for me.” And, you know, I think that he was in danger of dropping out of that program because of how hard it was for him to be the only man.

And I think that, you know, me being there and attending the class with him for a few days, and encouraging him and telling him that I was proud of him. I think it made a difference and whether he stuck with it. And he wound up graduating and getting a job cleaning hotel rooms. And he stands out to me because he was forced to think, “Well, is it more an affront to my masculinity to be in a classroom with women learning how to be a housekeeper or to not look after my family.” And he chose that it was more important as a man to be there for his family, not to worry about what it might look like that he had a job that men don’t traditionally have. And I just — it warmed my heart because I feel like that’s kind of the point of what I’m trying to do.

MARTIN: I don’t want to glide past the “you” in this because there is a sense of urgency to the work, because you have been sick.

JIVANI: Yes.

MARTIN: Right in the middle of finishing this book, you were diagnosed with a very serious, you know, illness, with Stage 4 lymphoma, as I understand it, and how are you doing?

JIVANI: I’m doing okay, I thankfully went into remission a few months ago, which has made my life a lot easier because I don’t have to stay at a hospital all the time anymore. I feel really good. But I still do feel that sense of urgency. I mean, when you stare death in the face, it really makes you feel motivated to go out in the world and share whatever it is you think you might have learned. And that’s how I feel at the moment. I think feel that urgency. It’s also where my desire to not be — to not feel like I’m, you know, put in a box comes from. Like I really want to feel like I can speak my mind as an individual and say what I believe is right, that I can try to put forward some sort of universal morality that everyone regardless of your circumstances might feel drawn to. And not to feel kind of limited by the same things that used to tick me off as a young man, which is people judge you and stereotype you and think that they know something about you because of what you look like.

MARTIN: Jamil Jivani, thanks so much for talking to us.

JIVANI: Thank you for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

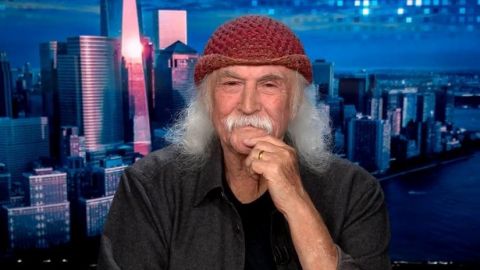

Kori Schake and Alistair Burt join Christiane Amanpour to discuss President Trump’s foreign policy challenges. David Crosby joins the program to discuss his life and music. Jamil Jivani sits down with Michel Martin to talk about his first book, “Why Young Men: Rage, Race and the Crisis of Identity.”

LEARN MORE