Read Transcript EXPAND

WALTER ISAACSON: Welcome to the show, Jill. Thanks for being here.

JILL LEPORE, AUTHOR: Thanks so much for having me.

ISAACSON: And on the best seller list with a scrawling, wonderful –

LEPORE: Who knew?

ISAACSON: — narrative history of the United States. Who knew? And your theme is in your title, “These Truths”, from one of the greatest sentences ever written, the second (inaudible) of the declaration. What are these truths?

LEPORE: Well these truths in the Declaration of Independence that are self evident, political equality, popular sovereignty and natural rights. And this is a nation that is founded on an idea, those particular three ideas, and unlike other countries that are founded on a common ancestry or a common heritage or a chain of leaders, this is a nation that is founded on those ideas. And so the way the book works is to try to figure out where did those ideas come from. They have a particular history and then to ask, you know, whether the course of American history since the founding has belied them.

ISAACSON: Well the – the idea of equality of course is written by the people who write both the declaration and the constitution, but as you point out in your book, if it’s Madison, you also do Billy his slave, George Washington you do Henry. You weave the slaves in with the people writing the constitution and the declaration. Why did you do that and what does that help teach?

LEPORE: Yes, so one of the things I want to call the readers’ attention to is the asymmetry of the historical records. We know so much about Madison, he’s endlessly fascinating, we know a lot less about the people that he owned as chattel, as property. And yet we are descended from both of those people, from all of those people. And to have to sort of struggle for racial equality and political equality in our day means having a richer history and a fuller history. So the – and a more integrated history, right, so people sort of would study, you know, presidential history or political history and then maybe also studied the history of slavery and emancipation and Jim Crowe and civil rights as if those are kind of separate tales, you know, you could tell them in separate books. But they’re – we know in our own day, these things, you know, Black Lives Matter and Obama’s presidency and Trump’s presidency are all part of the same world. So how to restore that sense of the interconnectedness and I think the causal relationships between those two things. There’s a big commitment that I – that I made in – again, giving it a shot, trying to lay out a story that – that holds together.

ISAACSON: And you also weave in women that way, we share a common interest in Benjamin Franklin and –

LEPORE: Yes.

(CROSS TALK)

ISAACSON: — what he did (ph) on his sister Jane, right. And tell me how that story wove in and you brought women into the narrative?

LEPORE: Yes, what I’m trying to – like with the history of race, there are these – there’s this sort of segregated history in our text books. With

women, they’re – they really remain pretty much left out of any account of political history. Women tend to sort of appear in 1848 and kind of curtsey and say we would like our rights and then they come back in 1920 and get the right to vote and then they appear sort of, you know, protesting the America – the beauty pageant or whatever, Miss America in 1968. And that’s kind of it and it makes no sense. It doesn’t explain the world we live in now where partisanship and struggles for women’s equality before the law are just explosively in confrontation with one another in our contemporary world. So I started out wanting to be a historian because I wanted to write women’s history and I ended up writing political history but trying to write political history that took women seriously as political actors. And one way I tried to do that here is both with, you know, individual characters we might want to know more about like Jane Franklin is quite – she’s just a compelling person. But also just thinking about all the decades when women didn’t have the right to vote and yet influenced American politics outside of electoral politics, through the work of moral suasion and the moral crusade, which becomes just a key feature of the American political style, the moral crusade that’s really brought into politics by women working as abolitionists. It’s fueled by the second great awakening of evangelical Christianity in the 1820s and ’30s, working for women’s rights, working for temperance, later for prohibition. In the 20th century, women’s moral crusades have generally moved to the right. McCarthyism can really be understood as a moral crusade really run by women. The pro-life movement of course is a moral crusade. You could think of the MeToo movement as a moral crusade too. Women have really consistent (inaudible) denied equal political power and the way that women have tended to try to influence politics has taken – has generally taken other forms that have – have big consequences for how our republic works.

ISAACSON: You talk about how the women involvement in politics has often been a very conservative thing. In fact, you highlight Phyllis Schlafly, one of the women who was part of the original I guess ’70s and ’80s – 1970s, ’80s, ’90s, the New Right movement against abortion and other things. Do you feel that in some ways women’s involvement, as you’ve said, is a conservative force as well as liberal?

LEPORE: It absolutely is both. I mean the – the women were really involved in the populous movement in the 19th century that is a left movement, but also was a nativist movement, has both what we would term liberal and conservative dimensions. It would – it wouldn’t – those labels wouldn’t have applied at the time. Prohibition is – is essentially a conservative movement. Schlafly is a good stand in for how conservative women have aligned over the course of the 20th century. She enters politics in the 1950s as a McCarthy supporter. She’s a – she’s a huge and really influential supporter of Barry Goldwater in 1964, and again even – and even before. And then she turns her attention to stopping the ERA after it passes Congress and goes to the state (ph) ratification in 1972, in part by conflating equal rights with abortion. And she’s just — the last dying act of Phyllis Schlafly was to endorse Donald Trump in 2016, she went to the Republican Nominating Convention in Cleveland. She endorsed him before he spoke at her funeral just before the election. There’s a really interesting trajectory there about women and conservativism that I think we’ve kind of lost sight of. And it – it – I wouldn’t say that it explains everything in the world, but it’s an important piece of an explanation of the second half of the –

ISAACSON: And it’s interesting that you say that liberals have left out some of this conservative strand in women’s politics. Is your book – do you consider it ideological at all in your approach to American history, meaning coming from a liberal side or coming from a conservative side?

LEPORE: So I was actually trying to reject the highly ideological interpretations of American history that we have been kind of stuck with on the one hand – we have a sort of polarized past, people kind of line up there. I mean less – scholars don’t do this, politicians do this. They offer – you know, there’s a kind of conservative version of American history and then there’s a liberal version of American history. And with this book I would like to illicit a conversation about whether we can have a shared past, because I don’t know how these partisan divisions that make it impossible for us, you know, to formulate a budget to complete a full Supreme Court to pass pretty much any legislation. And I think most importantly to think deeply about the need for political reform, we have a lot of conversation in our country about resistance and revolution, and I think there’s so much wrong structurally that we really ought to be having reform conversations as well. And that’s the spirit in which I – I – I tried to offer this account. Not to dilute – dilute something or be wishy-washy about things, but to just take seriously that this is a set of things that did happen and here’s my interpretation of them.

ISAACSON: Now all of this seems to culminate both the strands, women rights both on the liberal and progressive side, and as you point out so well in the book on the conservative side, in the Kavanaugh hearings and the MeToo moment that we’re going through, how do you react to that? How do you see the history leading us to that and where will it go?

LEPORE: Yes. I think that’s the intersection of two different developments. One is the changing relationship between the public and the Supreme Court, largely through the nomination process, but and the other is women struggle to gain equal protection of the law and I think we think about that more squarely when we look at that, those confrontations, we’re thinking about, well wow, if all the violence against women and sexual harassment laws and sexual assault laws have been passed in the 1970s had been enforced, we wouldn’t be here now. We’re here because that didn’t succeed. Many women don’t have equal rights and they don’t have equal protection. I think that’s the visible piece of what’s going on now, separate from like the partisan piece of it. But the Supreme Court public opinion is a thing that actually kind of distracts me and captures my attention here, because throughout the 19th century generally when president named a new Justice, the decision just went to the whole of the Senate, which is voted up or down and they almost always voted up. It doesn’t even really go to Committee. When it started going to Committee, the Committee maybe had a few deliberations and they voted up or down and sent it to the Senate. The first Justice nominee to appear before the Senate was in 1925. Like the idea that people are supposed to go and be interrogated before the Senate Judiciary Committee, that’s a very recent development on our history and that was just a weird kind of one-off until 1939 when Felix Frankfurter was called to answer the charges he was a communist and he agreed to go. And the only reason he was asked was because you go black in 1939, he’d been nominated by FDR after he got through the Senate it was revealed that he had been in the KKK and the Senate thought, whoa, we should have brought him before the Committee and asked him about that. So, it’s not until 1955 that it’s even regular that nominees appear and since 1987 that that is a television spectacle. That is, of course, the Robert Bork televised hearings, which is really the last spectacle of the Watergate hearing, honestly, I think is the best way to think about Bork.

But, now we have this notion, ever since the Merrick Garland situation, when Mitch McConnell said the American people will decide our next Justice. That’s actually now how it’s set up. It’s not a popularly — it’s not an elected position. It’s an appointment for (inaudible) to be insulated from public opinion. So, I think it’s quite troubling to imagine that Twitter is deciding who will hold the next seat on the Supreme Court.

ISAACSON: One of the themes in your work and Einstein once said it, is that in American Democracy there seems to be gyroscope, just when it’s tipping one way it knows how to right itself. Do you think we have, in our history, in our DNA, and going forward, the mechanisms to right ourselves when we seem to have become so divided?

LEPORE: I do. I do. Whether that will happen, I don’t know. And I work pretty hard to hold onto that hope. I think a lot about the speech that Frederick Douglas gave in 1894, shortly before his death, to an audience of school children in Manassas, Virginia, black school children, and he — think about everything that he had achieved that had been undone. Right? He fought for emancipation, for abolition, emancipation and equal rights and by 1894, right, the Civil War has been won, the emancipation happened, but Jim Crow has taken over. The South wins the peace, there’s violent segregation and an epidemic of lynching and he tells these school children to hope that what is necessary in challenging times and the more challenging the times are is to do the hard work of figuring out where hope lies.

ISAACSON: Jill Lepore, thank you so much for being with us.

LEPORE: Thanks for having me.

About This Episode EXPAND

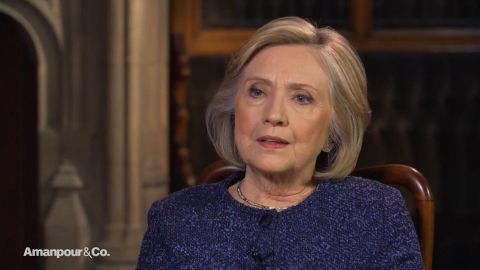

Christiane Amanpour interviews Hillary Clinton in an exclusive sit down and speaks with author Mark Urban. Walter Isaacson speaks with author and historian Jill Lepore.

LEARN MORE