Read Transcript EXPAND

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: What is Dying of Whiteness?

METZL: Dying of Whiteness is a story about the politics that claim to make white America great again. If you’re a working class white American end up making your own life harder, sicker and shorter. I spent seven or eight years over the course of my research looking at the everyday effects of what happens if you’re a working class white American and you live in a state that had policies like cutting away healthcare and blocking the Affordable Care Act, allowing the easy flow of guns, massive tax cuts, the defunded roads, bridges and schools. And what I found was that those policies that were supposed to make your life great ended up from a health perspective, making your own life as dangerous as risky as did secondhand smoke or asbestos or car crashes. These policies themselves really functioned as risks to your own health.

SREENIVASAN: So what is whiteness in the context of this book?

METZL: What I look at is really what I call a racial resentment I think to whiteness. And so what I’m tracking is a story of the ways that politics that are anti immigrant, anti government, pro gun, kind of what are called backlash politics. They’re couched in a kind of racial resentment. This resentment that basically minorities or immigrants are taking away privileges that are due to white Americans. What I track is the ways that those anxieties work their way into state level policies and then into national level policies.

SREENIVASAN: You’re separating out that this is not because people are racist but that the policies have racist component.

METZL: I interviewed many people over seven or eight years for this book. I certainly encountered many examples of overtly racist sentiments, no doubt about that. But ultimately what I found is that the health risk to working-class Americans came not from their individual racism or intentions. I didn’t really try to assess what’s in somebody’s heart. I didn’t know and I think that’s very complicated. What I found was that the risk came if you live in a county, city or state that had these kind of racially anxious or racial backlash policies that dictate your health in a way.

SREENIVASAN: These backlash policies, I mean this is a long time coming. This is not just from the election of Donald Trump or a specific event.

METZL: What we’re seeing right now is that these tensions that have been brewing for quite some time, these concerns again about immigration, about taking away people’s firearms, about the over spread of government, you’re absolutely right, they’ve been brewing since the ’40s, ’50s and ’60s but right now I think is a particularly urgent issue because these policies that have been localized just to either the extreme right or to particular states, now are impacting national policy and so the implications are much broader.

SREENIVASAN: Before we get into the case studies, somebody is going to look at this and say, “Look, he is open in saying he comes from a family of Democrats even though he interviewed all of these peoples.” How do we separate your own biases coming into these interviews?

METZL: I try to be very open about my own background and not just in the book and I write about that quite a bit, but also in the people I spoke with. And part of my intention is that I’m trying to find some kind of middle ground. In other words, here are urgent issues of life and death and it wasn’t like I made any kind of assumption that I’m on the side for wanting longer life and they wanted shorter life. Part of what I was studying was the frameworks of whiteness, why is it hard to talk about whiteness. And so in a way that I didn’t want to create this category of us and them, but it was also an education for me. And because I learned the full extent to which people identify what these politics. So this liberal idea that people are just going to get talked out of their support for Trump when they see particular effects, I hope my book puts that to rest.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. Let’s talk a little bit about Missouri, this is the State where you grew up in Kansas City, you got your medical degree there, but yet you say that it’s really – gun policy there is worth taking a very close look at, why?

METZL: Missouri is a very interesting example of this particular dynamic. The Missouri that I grew up and the Kansas City that I grew up in had some – what I felt at the time and everybody felt at the time to be some quite common sense gun laws. In other words before 2007, 2008, you could carry a gun in Kansas or Missouri. There were long histories of hunting traditions of gun ownership. But you had to go to the sheriff’s office or go through a process in order to get a particular permit. And what starts happening in 2008 is a steady erosion of the kind of laws and regulations that govern how people buy guns, where they can carry guns, and what you see are dramatic expansions in just rates of gun ownership in the State and that goes hand-in-hand with increasing rates of gun trauma, gun shooting, factors like that. And I found some pretty shocking trends on one hand. Many of the people I spoke within African-American communities ironically felt that having a bunch of people around with guns was a form of intimidation. One man I spoke with outside of Kansas City told me that an African-American, a Vietnam vet. He told me that he didn’t go to Sam’s Club anymore because there were all these white guys walking down the aisles with guns as if they were in the Wild West and he felt like they were trying to intimidate him and I heard that again and again. On the flip side, I spoke with many white Americans. I went to very quite pro-gun areas and I talked to them and really gained an understanding of how they saw guns as part of their identity in a way. Part of their political identity, part of their racial identity.

SREENIVASAN: You even went to, well, groups or parents of or loved ones of people who have died by suicide or talking basically group therapy sessions, and the data that you find that correlates between the rates at which white non-Hispanics die in Missouri compared to anywhere else is startling.

METZL: So the group I went to in Missouri was in a way support group for families who had lost children, parents, cousins, friends, boyfriends to gun suicide. I wasn’t there to be pro or anti gun. I really wanted to ask people how do you balance being pro-gun in the way that you are and also pro safety. And this seemed like an urgent moment to ask them and what I found I thought was pretty interesting, which was that it didn’t really change people’s ideas about gun politics. In other words, if I had an idea that somebody at that moment was going to change their idea about guns, that was not the case. People were just as devoted to their guns at that time.

SREENIVASAN: Even though they had lost a loved one to a death by a gun suicide, their beliefs were still steadfast.

METZL: Well, what I’m saying is that it actually mattered how I asked the question. And so if I asked them, “Did this change your view about guns?” They would always answer me, “We’re pro-gun,” or, “This is gun country.” So because that question implied that I was making a judgment or that I was down there with an agenda. If I said, “What can we do to create better safety in our communities? What can we do to have safer societies even if we have a lot of guns?” I felt like people were much more willing to talk to me about ideas that they had. In Missouri, the minute that guns became easier to obtain, this was a great thing for some people. They felt like it was much more freedom, much more authority. They could carry guns in public. It was their constitutional mandate. But if you just track healthcare, Missouri starts to inch up in terms of a particular silent risk factor which is white male suicide. So all of a sudden Missouri starts to set the graph on these kind of deaths of despair, but often rural white men who take their own lives by suicide. And so what I found tracking Missouri is that there was a loss of hundreds of thousands of what I call lost white male life years and a dramatic, dramatic cost to the to the State itself because the cost of not having white men working cost the State about $300 million just in the first couple of years alone.

SREENIVASAN: Let’s shift to Tennessee where you work now and you live some of the time and you’re talking about Tennesseans making decisions against their own better health interests by refusing for Medicaid expansion, right?

METZL: I did focus groups along with some of my colleagues with white and black men who were middle and low-income in Tennessee. It was the profound ways in which people’s political ideology pushed them into positions where they were rejecting health care reform even if that health care reform would have met their own needs in quite dramatic ways. So I met a man named Trevor who was quite medically ill. He had a series of chronic medical conditions and came to the focus-group. With an oxygen mask he was having a hard time breathing, he was having problems with his liver. He was somebody who very badly needed health and support. He was also living in a low-income housing facility that was partially funded by the government. And when I asked him, “Gosh, what’s your feeling about the potential of healthcare reform?” He said, “Look, I know I’m dying. I know that I have a very unhealthy lifestyle. I know that I could benefit from treatment, but I want to tell you that I’m not going to support the Affordable Care Act because it means that my tax dollars are going to go to lazy minorities and immigrants.” And so in a way what he was saying was that his idea of this particular ideology was so profound that even on death’s doorstep he was unwilling to think about a government program that might benefit everyone. And for me what this spoke to was this bigger, bigger ideology about this concern, this concern about somebody taking away what’s mine. If you live in Tennessee and you are a white American and your State as Tennessee was basically effectively blocked the expansion of the Affordable Care Act, you’re going to live about a two to three week shorter lifespan, and so the question is are your politics worth three weeks of life, that’s probably an open debate.

SREENIVASAN: Is there an identity there that they’re bonding into? I mean, is there a resistance that they feel a part of?

METZL: The issues themselves become racial identities. The minute we’re talking about Obamacare or guns or tax cuts, the minute they become caught up in the American political system right now, they become racial identities. And so it’s absolutely the case that people’s racial identity, in other words this is what means to be a Republican, this is what it means to be right depended on them taking up a position in this case in Tennessee that was against the against the Affordable Care Act.

SREENIVASAN: You took a look at Kansas and Kansas famously rolled back taxes and infrastructure funding significantly and it was a big test really for the rest of the country that we’re watching that, what happened?

METZL: Kansas was the testing ground for what became the GOP tax bill that was passed in 2016. Kansas basically had a Governor, Sam Brownback, who enacted massive tax cuts across the State and cut away funding for roads, bridges, schools. Including the schools that many of his supporters’ children attended. The promise at the time was that this was going to create a renaissance of prosperity. It was a renaissance of prosperity for many upper income people, but lower income people and middle income people saw steady decay of the support systems of their lives and so they saw their infrastructure fail, roads got less attention, bridges started to fall apart. And probably the most shocking part was that the school system, Kansas, had this fantastic school system. It used to be in the top ten in the country and it fell to the mid 40s in terms of reading and math proficiency and also what you saw was that people started to drop out of high school. And because these were affecting many people, actually across the board what would I show in the book is that dropping out of high school correlates with about a seven to nine-year shorter life expectancy when you aggregate that.

SREENIVASAN: How does that work?

METZL: Well, basically if you drop out of high school, you have fewer career opportunities, fewer opportunities to access healthcare. You probably might not have health insurance that might lead you into different kinds of decisions. And so it was actually relatively straightforward math and the nine year life expectancy has been reproduced in other studies and I just applied that to Kansas and what I saw was that this was leading to a dramatic decrease to potential white life years.

SREENIVASAN: But it seems the conservatives want a scapegoat, the poor, while liberals on a scapegoat, the rich.

METZL: What I did find powerful in talking to many conservative voters was I think you’re exactly right that their concern was always directed downward. In other words, people who were suffering ill health in these focus groups in Tennessee, their concerns were the people below them who were nipping at their heels potentially — immigrants or minorities, but they never look up. They never thought, “Gosh, maybe a corporation is benefiting from my bad state, maybe wealthy people who receive the benefits of these particular tax cuts.” And so in a way there quite a shortage of looking upwards, whereas I think you’re exactly right, the dynamic is exactly opposite, potentially for some of the liberal politics that we’re seeing right now.

SREENIVASAN: You point out that whites in specific are voting against their health interests or their biological interest, but it’s pretty bipartisan and cross-racial, I mean, Democrats do it, minorities do it.

METZL: We do it all the time. And so, again, I want to be quite clear about that this is not just a Republican thing. We make decisions that are bad for our health all of the time. And, I mean, give it credit these policies if you want to be on the winning team, I mean probably people in many of the areas that I talked to said, “Well, hey, buddy, were winning election so don’t try to talk me out of my politics.” There’s a long history of democratic initiatives from urban policies, to policies about HIV, to issues that led up to the opioid epidemic and others that are not just linked to one particular party. So I’m not trying to say that everybody should become a Democrat in this book. Part of what I’m saying is that these ideologies of race and inability to talk about whiteness in this country leads us to polarizing positions that make it hard for us to work back from.

SREENIVASAN: A Republican white male that you might have interviewed in this book, for this book would say, “You know what, the reason that I’m not taking this, I’m part of this resistance. I really firmly believe philosophically that my opposition to this matters because it will be better for the country if the Affordable Care Act doesn’t work or if there’s greater access to weapons or guns.”

METZL: This book is an object lesson and a lesson that I think that liberals were very slow to respond to, which was the depth of commitment that many working-class white Americans had two particular positions even if those positions were bad to them. People were quite literally willing to lay down on the tracks, put their own lives. I mean, in Kansas people were willing to support tax cuts that affected their own kids’ schools and I think liberals really missed that. They missed the depth of that particular kind of commitment. And certainly for people who care about particular social issues like the courts and abortion and factors like that, that felt like a fair trade-off for them and, again, I think that’s an important point. This is a book about the depth of that commitment to those positions.

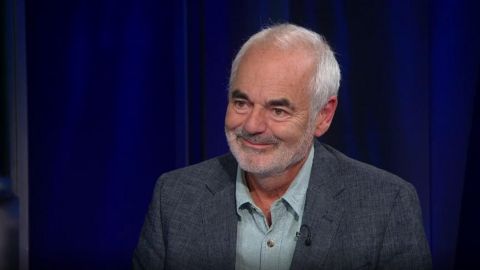

SREENIVASAN: All right the book is called Dying of Whiteness. Jonathan Metzl, thanks so much.

METZL: Thank you so much.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Yale University students Anna McNeil & Eliana Singer about the lawsuit they are bringing against the university; and author David Spiegelhalter about the importance of statistics. Hari Sreenivasan speaks with physician Jonathan Metzl about his new book “Dying of Whiteness.”

LEARN MORE