Read Transcript EXPAND

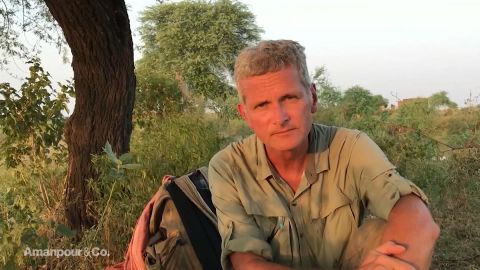

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, it is commonly said that a journey of a thousand miles begins with one step. But what about a feat on foot around the entire globe? Meet Paul Salopek, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, a National Geographic Fellow. He is tracking the route our ancestors took on their global migration telling important stories along the way such as climate change. Paul spoke to our Hari Sreenivasan from the outskirts of Delhi in India, 11,000 miles away after setting out.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Paul, for viewers who might be unfamiliar with the how or the why, let’s talk about that first. Why take this journey?

PAUL SALOPEK, JOURNALIST AND NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC FELLOW: This is at its core a storytelling journey. I’ve had a long background in foreign corresponding. I’ve been a journalist covering the world for more than 20 years for newspapers. And I noticed in my coverage that I was missing big gaps of the stories that I was encountering across the globe by going too quickly, by flying over them literally in many cases. So the Out of Eden Walk is an experiment, kind of a global laboratory for slowing myself down so that we can dive deeper into the stories of the ordinary people who inhabit the major headlines of our day. It’s a walked investigation of the world.

SREENIVASAN: How long has this been going on? How many countries? I remember the first time we spoke, you said you’re going to be done in about seven years.

SALOPEK: That’s true. And that was a bit of an optimistic projection. I have been walking since January of 2013 and I originally projected this long foot journey to last about seven years based on a mathematical calculation of, you know, walking half the time and stopping to report stories half the time. The concept of the project, the blueprint, the map for it intellectually is to follow the footprints of the first homo sapiens who migrated out of Africa back in the place to see, back in the Stone Age. You know, about 60 to 100,000 years ago.

SREENIVASAN: What have been the biggest hurdles in [13:45:00] this? A mountain range or don’t really care where humans drew lines on a map?

SALOPEK: So I started in Ethiopia in 2013. I’ve walked up the Rift Valley of Africa. I have crossed over by camel ship to Saudi Arabia, walked through major deserts in Saudi Arabia, the Hejaz, where the temperature was every day above 100 degrees. I’ve crossed the Caucasus mountains in the winter through blizzards. I’ve crossed the Hindu Kush in the autumn through blizzards. So yes, I think physical obstacles are significant to me. They’re kind of my natural deadline.

SREENIVASAN: You’ve walked with all kinds of people who are leaving where they were.

SALOPEK: That’s true. And today, as you know, there are more than ever. I mean U.N. statistics vary but anything up close to 270 to 300 million people now work and live outside of the countries where they were born and it’s not always associated with violence or wars or suffering. It’s people going to seek opportunities. So in a strange way, we cycle back into kind of a golden age of migration that’s a bit of a return to our roots.

SREENIVASAN: There were periods where you were walking alongside refugees from the Syrian War.

SALOPEK: One of the ironies of the Out of Eden Walk is that I bumped into one of the biggest force migrations in modern history, which is migrants, refugees fleeing mass violence in the war in Syria. In that situation, I was walking through basically countryside in Turkey and started seeing tent camps everywhere. There were people camped out under orchards. There were people camped out on the outskirts of towns. There are people collected into the large refugee camps. I think the numbers at the time, this was in 2014, about 11 million people had been uprooted by the Civil War in Syria. Walking may be a bit more empathetic because I was literally at a high level with the refugees who were also fleeing on foot from their war-ravaged cities.

SREENIVASAN: How are societies that you’ve walked through dealing with the costs of climate change?

SALOPEK: Not well. When it comes to climate change, I have walked through several landscapes that have been very significantly impacted by changing weather that is going to be long term. The first was in Ethiopia where that part of the Rift Valley was experiencing increasingly erratic rainfall. It’s already dry. I mean imagine a tan desert, the sparse brash, brittle yellow grass has bursts of rainfall during its rainy seasons. There are temporary rivers that burst to life but then fade away and sink very quickly back into the sand. And the people who live there are adapted to that and have adapted that cycle for a thousand years. Now that the rains become more erratic, now that’s moving around more and is less predictable, it started conflicts between these pastoral groups that depend on that grass and depend on that rain for their animals. So sadly, this is one case where changing climate is exacerbating violence between human beings. And how is the government handling it? By basically encouraging these people to move off the land. In Central Asia, there were — there was the heaviest rainfall in living memory. I interviewed 90-year-old people who never had seen the rains that they did in Kazakhstan and the steps had grown so high with so many new kinds of plants that they didn’t have the names of these plants in their folklore. These are seeds that have been lying there for, you know, once in a century kind of flood events.

SREENIVASAN: Paul, recently you wrote about water scarcity in the region that you just walked through in the Punjab.

SALOPEK: Yes. Water scarcity is a big issue in India. There are more than 1.2 billion people here and the government by its own admission has found that more than half, 600 million of them, are living in some form of a water crisis. It comes in two forms. It’s either water that’s contaminated and is not drinkable, not usable or it’s simply a scarcity of water. And what I saw coming through this landscape, Hari, imagine the Punjab, it’s as heavily industrialized in terms of agriculture as the Midwest in the U.S. It’s turned India into a food exporter. They’re using so much water that it’s like spending your life’s blood to keep yourself alive. And I’ve interviewed farmers along the way whose water tables has dropped hundreds of feet, not in a generation, in a decade. And when I ask them, well, what are you going to do when your bore well, your little pump pumping up the water from this precious reserve of antique water that will never be replaced, what are you going to do when that runs out? And they sort of shrug. They don’t know.

SREENIVASAN: You frequently mentioned you’re walking partners, you’re kind of building this global [13:50:00] family of people who are walking with you few through all these years.

SALOPEK: I think it’s one of the great rewards. Probably I would say the greatest reward of this project so far is having the privilege of walking with so many sterling people, so many amazing people who have given me their time, have opened up their homes to me, literally their home countries to me. And they include everybody from churches, photographers to Saudi Bedouins to shepherds in Pakistan. And now I’m walking with Zig Agarwal who’s a man who walks out the rivers of India. He’s teaching about river ecology here.

SREENIVASAN: I’m sure one of the questions that people have is about your security situation. What has that been like as you’ve been walking through so many different countries?

SALOPEK: Yes, I get that question a lot and it’s a valid question because I’m not naive. I was a war correspondent for many years and I’ve seen just how badly we can treat each other. But I must say I’ve been very lucky. So far in almost six years of walking, I think the actual total journey right now is about 11,000 miles is we treat each other pretty well. There have been a few incidents like in Eastern Turkey where I was ambushed a couple times in the conflict between the Kurds and the Turks. Those were cases of mistaken identity. The Religare parties, people who ambushed me, thought I was with the opposition, the enemy. I was shot at in the West Bank by the IDF, the Israeli army, another case I think of mistaken identity. But I can remember those incidents so clearly because they’re so few.

SREENIVASAN: You’ve also been detained a number of times. You have a separate map just keeping track of that.

SALOPEK: Yes, my police map. I started being stopped by police almost immediately even in the most remote corner of the Rift Valley of Ethiopia, you know, deserts. They are the far region of north. I was starting to be stopped by police because look, let’s face it, you know, we live in a motorized world increasingly. So it’s unusual to see anybody kind of walking along a road these days except for places like India where people still do it as a form of work and pilgrimage. And especially if you look like me, right. You know, my skin, you know, the way I look, my clothing, I stand out. So I get stopped often. And so I thought why not start geotagging these stops and describing them and putting them into categories of friendly police stops, kind of neutral police stops, and then kind of hostile police stops. And then pouring them into a map, the digital map as an anecdotal way to kind of show freedom of movement across the world, right. You can tell something about societies, about the way their security officers treat their citizens or treat anybody. So that map is up there. I’ve been stopped close to 90 times so far.

SREENIVASAN: Can you give us a sense of the logistics? Do you just sleep in people’s homes? How does it work?

SALOPEK: I sleep wherever the sundown catches me. So if I’m walking through a desert, I camp. And if I’m walking through a rural landscape such as this in Central India, I either stay with a family or at an ashram, a temple or at a roadside dhaba like a mom and pop shop that sells, you know, food truckers. They sometimes have tables you can sleep on or rope beds you can sleep on, Vagabond’s hotels. And then when I’m in big cities, of course, I do what everybody else does. I stay in a hotel and I take a shower and wash my clothes.

SREENIVASAN: How have you stayed so healthy? I mean just the different types of food that you’re eating, the possible waterborne illnesses, the viruses.

SALOPEK: Yes. Well, I’ve certainly been exposed to the gamut of microorganisms, you know, ranging from kind of near Arctic environment to tropical ones. But here’s the thing, I’ve been pretty healthy. I got sick twice. In the last six years, I got pneumonia in Palestine and I got an infection in Lahore in Pakistan that knocked off my feet for about a week. But other than that, I’ve been pretty healthy. I think it’s two reasons. One is walking keep you pretty healthy, right. It’s a little form of exercise, keeps the heart healthy, keeps the mind happy. So that’s one thing. And the other is by moving slowly through these new environments, I think my body has time to adapt.

SREENIVASAN: So what is next? You’re in India now. What happens after?

SALOPEK: I’ll be pivoting northeast into Myanmar and then crossing the border to China and walking across China and it will take more than a year. And from there, cross the Alma River into Siberia and then walk as far north in Siberia as I can get before the weather just turns so impossible to make walking impossible. Take a ship to North America and then walk down the western coast of the New World to the very tip of South America to Tierra del Fuego. And that’s the last corner of the world that scientists or ancestors reached and colonized way back in the Stone Age.

SREENIVASAN: Paul Salopek, thanks so much for joining us.

SALOPEK: It’s a pleasure.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane Amanpour speaks with Ali Shihabi, founder of the Arabia Foundation, about U.S./Saudi relations; and U.S. Rep Adam Schiff about Michael Cohen’s guilty plea. Hari Sreenivasan speaks with Paul Salopek, journalist and National Geographic Fellow, who is trekking across the globe on the route our ancestors took to tell the stories he learns along the way.

LEARN MORE