Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

DAVID CAMERON, FORMER BRITISH PRIME MINISTER: I learned as prime minister that we have to focus more and more on the most fragile states, where

progress has been hardest.

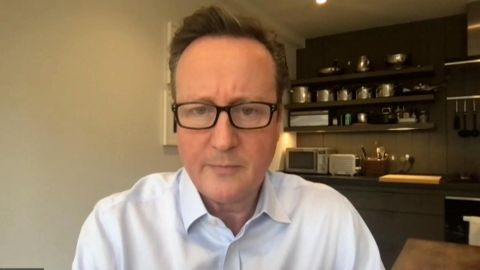

AMANPOUR (voice-over): David Cameron makes the moral case for helping the world’s poor. The former British prime minister joins us for an exclusive

interview about his new green energy initiative, COVID and Brexit.

Then:

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: All my life, this is what I wanted to know. This is just incredible.

AMANPOUR: Shocking discoveries through DNA. Tech and business reporter Samuel Burke reveals the most surprising genealogical journeys that he’s

investigated for his new podcast, “Suddenly Family.”

And:

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: We’re producing several millions of vaccines every month.

AMANPOUR: Moscow’s vaccine diplomacy. We get an exclusive look inside a Russian factory producing these doses.

Plus:

JULIA MARCUS, INFECTIOUS DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGIST, HARVARD UNIVERSITY: We could potentially eliminate risk in some scenario, where humans could

remain completely isolated for some time, but that’s just not possible.

AMANPOUR: How to think about risk. Infectious disease epidemiologist Dr. Julia Marcus talks to our Hari Sreenivasan about public messaging during a

pandemic.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Ghana in West Africa today received a planeload of COVID vaccines. It is the first country in the developing world to benefit from the COVAX

vaccine-sharing program; 600,000 doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine were unloaded this morning in the capital, Accra.

Very few people in the world’s poorest nations have been vaccinated. And it’s a stark contrast to the tens of millions who’ve gotten their shots in

the Middle East, Europe and the United States.

The COVID pandemic has exposed inequality and growing the gap between the global rich and poor.

Former British Prime Minister David Cameron wants to redirect focus onto fragile states, those beset by conflict corruption, and now the pandemic,

and where basic health, economic and energy infrastructure is dire.

I spoke to Cameron about the moral duty of the rich world as he launched his appeal today with a focus on the power of green jobs and technology.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Prime Minister Cameron, welcome to the program.

CAMERON: It’s great to be with you.

AMANPOUR: So, you are co-chairing this initiative. It’s about fragile states. It’s about poverty, COVID. It’s about climate.

You have said that the government here and elsewhere, governments need to be really muscular in intervention, how to build back better after this

pandemic. What do you mean?

CAMERON: Well, why we — first of all, why should we focus on fragile states?

I mean, the truth is, if you look at global poverty, more and more of the world’s poor are going to be living in these countries, countries like

Somalia, or Burundi, or Sierra Leone, countries that have really struggled to make progress over the last 20, 30, 40 years.

The very poor in India and China will probably be lifted out of poverty by the growth in those countries. And I learned, as prime minister, that we

have to focus more and more on the most fragile states, where progress has been hardest.

And these are the most difficult to help, because they tend to be affected by a whole range of things, from corruption, to conflict, to weak state

institutions, lack of consent for government, often recovering from terrible wars and crises.

But if we don’t focus on these states, we’re never going to hit all those goals and targets and development agendas that we’re also keen on. And

also, I think, as the prime minister of a First World country, I could see that, when fragile states go wrong, the problems that they deliver, whether

that’s piracy, or terrorism, or mass migration, they come and visit us.

So, my message to my successors is, keep developing — keep focusing on development, and keep focusing on fragile states, because that’s where the

very poor increasingly live.

And this initiative really is about saying, access to electricity is an absolute key for helping people out of poverty. We have made huge progress

over the last 10 years in connecting more people, but not in the fragile states. There are still 800 million people in our world that aren’t

connected to electricity.

And that’s what this call to action, this initiative that the Council on State Fragility is making today.

AMANPOUR: OK.

Well, look, you have just made a huge call for government intervention and First World government responsibility.

Your own country, the U.K., under this government, has cut back its foreign aid budget and its contribution, after you raised it to a certain

percentage.

I mean, how is this going to happen if even the country that you used to be prime minister of is cutting back, instead of going forward?

CAMERON: Well, I think the United Kingdom has made a mistake. I was very proud to agree to the target of 0.7 percent of gross national income going

in aid payments.

But, more importantly, prior achieving that in government in 2014, the first and really the only of the major developed countries to do that, and

I think it’s not only a tragedy, but also a mistake that we are coming off that 0.7.

But even with our new budget of 0.5 percent of gross national income, Britain will still be one of the biggest aid donors in the world, probably

still the biggest in Europe by some margin in terms of deployable aid, and so able to participate and lead with initiatives like this, connecting up

those 800 million people all around the world who have no access to electricity.

And the truth of it is, this used to be incredibly difficult, incredibly expensive. Now it is actually relatively cheap, because we have these new

green energies, like solar power, where the prices have been plummeting.

And it is much more possible, because you can have distributed energy systems. You don’t have to have some massive grid and great big power

stations. You can go down to the level of one solar panel, one battery and one lamp. And that can hugely help families when they’re — whether they

want light, or whether the children want to learn to read, or whether you need to charge your mobile phone.

So, what was difficult has become possible.

AMANPOUR: So, you have already made the case for why it has to happen. It’s a moral case, but it’s also a pragmatic case. I mean, a rich country

like Britain might say, why do we need to bother? But you have said that because those problems will come and hit us.

So, that’s that case. But what about the ideological case? The — let’s face it, the hard-line conservative thought over the last many years has

been lack of intervention, let the free market do its business, and everything will sort itself out.

Do you believe that still applicable now?

CAMERON: Well, I’m a huge supporter of enterprise economics, of letting markets work, of encouraging people to start businesses and employ people.

That is where growth comes from.

And if you look at the most fragile states, which is the concern of the Council on State Fragility, one of the things they all tend to lack is a

healthy private sector of small- and medium-sized firms. So, that’s absolutely vital.

But to get that healthy infrastructure of small- and medium-sized firms, you do need to be quite muscular in your intervention in the fragile

states. You need to have a property rights system that works. You need to have a tax system that works. You need to have a rule of law that works.

You need to have an absence of corruption. All those things take, if you like, muscular intervention.

What I was talking about in terms of the U.K. and the Western countries, as we build back, if we want to see green growth, if we want to see, as we

return to growth, that being green and sustainable growth, that does take government setting the frameworks.

And while I ran a very pro-enterprise, market-based policy, in terms of the U.K., where we had a massive expansion when I was prime minister of wind

energy, of solar power, we really dialed down coal more than virtually any other European country, that did take quite a interventionist framework,

and we need to continue with that if we’re all going to make our contribution to meeting the climate change goals that we need to.

AMANPOUR: So, I’m just going to play a little sound bite, to this end, by Sir David Attenborough, a British national treasure and the greatest

naturalist in the world.

This is what he said:

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SIR DAVID ATTENBOROUGH, NATURALIST: Please make no mistake. Climate change is the biggest threat to security that modern humans have ever faced.

I don’t envy you the responsibility that this places on all of you and your governments. We have left the stable and secure climatic period that gave

birth to our civilizations. There is no going back.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: He addressed the U.N. Security Council on this very issue, David Cameron, that you’re bringing up right now.

Do you think governments actually recognize the tipping point that our civilization is at?

CAMERON: I think that, by and large, they do. And I’m actually an optimist about what can be achieved this year.

If you take the United Kingdom, we proved, when I was prime minister, that you can grow an economy while cutting your carbon emissions. So, we have

seriously started the process of decarbonizing our economy.

We have become the biggest offshore wind player in the world. Something like 98 percent of the solar panels we have in the U.K. were installed in

the six years while I was prime minister. So, huge steps have been taken.

And I pay tribute to my predecessors in the Labor Party, who put in place some of the climate change legislation, which I backed as leader of the

opposition, and has delivered this very strong green performance for Britain. So, we have shown a First World, wealthy country can do it.

What we now need is for all those countries to act in that way. And why I’m an optimist is, you have got a new president in the United States who has

signed back up to the Paris climate agenda. While the Chinese are setting targets that aren’t as aggressive as I would like, they are at least

setting targets and joining in the discussion.

I think you see moves in other parts of the developed world. But this won’t work if we leave the poorest countries and the poorest people behind.

AMANPOUR: Well, Attenborough also goes on to say that leaders should “recognize their moral responsibility that wealthy nations have to the rest

of the world.”

And your — one of your co-chairs of this new initiative is the former prime minister of Liberia, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. And she has said that

COVID has derailed decades of progress on extreme poverty. And many, like the IMF and all these global internationalists and economists are now

saying, austerity is not what we need to do right now.

CAMERON: Well, first of all, let’s deal with this issue, as you rightly say, that COVID has resulted in the first increase in absolute poverty in

our world for 30 years.

In the whole period of time I have been active in politics, we have had great success of lifting the poorest people out of poverty. And my focus is

on fragile states, because that’s where the battle is toughest. So, far from cutting aid budgets, we should be actually making sure we deploy them

properly.

And I continue to make that argument.

Let me answer directly on the issue of austerity. I mean, when I became prime minister in 2010, Britain was due to have the biggest budget deficit

anywhere in the world, not just the developed world, but the whole world. And I thought it was essential over time to get our finances in order. And

I believed that that would contribute to our growth performance.

And it did. I mean, by the time I left office, we were the fastest growing country in the G7. We have created millions of jobs. Millions of new

businesses have been set up. But, today, we do face very different circumstances.

So piling, say, tax increases on top of that, before you have even opened up the economy, wouldn’t make any sense at all. So I think it’s been right

for the government here in the U.K., governments around the world to recognize this is more like a sort of wartime situation.

AMANPOUR: So, add to that, of course, the Brexit effect. And I’m going to ask you again, as I have asked you in the past, do you believe what —

because you’re seeing now some of the unbelievable problems that businesses are having.

The trade deal that was struck obviously leaves out a huge sector of the British economy, the service economy, the financial institutions that make

the bulk of this economy.

Would you say that those who labeled you Project Fear in the run-up to the Brexit referendum were right or wrong? I mean, the figures show that the

economy’s taken a massive hit. And it’s not just because of COVID.

CAMERON: Well, I continue to believe that the right answer was to stay in the European Union on the amended terms that I had achieved. But I lost

that referendum. I fought it with everything I had. I put across all the arguments I could.

I think what we’re seeing now is both some early problems that need to be addressed, but some of them are the consequence of being outside of the

single market. So, I hope the government can address as many of the problems and issues as possible, whether that’s problems faced by British

fishermen, whether it is small businesses that are finding it more difficult to export to E.U. countries because of the additional

bureaucracy.

I hope they can tackle as many of these problems as possible. But, ultimately, some of them are because we chose to leave the single market…

AMANPOUR: Right.

CAMERON: … and become a third country.

But, again, I am an optimist. Britain is a major economic power, was either the fifth or sixth largest economy in the world. We have had a very

difficult time under COVID. I believe we will bounce back, as a country of our size should be able to form a relationship with the E.U. that says,

look, we’re no longer members, but we want to be friends and partners and neighbors, and in many ways your best partner, whether it comes to trade or

investment or tackling problems of global poverty, all the things we’re talking about today in terms of delivering electricity connections to

millions of people around the world.

Britain is still — we have got the biggest defense budget in Europe. We have got the biggest aid budget in Europe. We have got one of the best

diplomatic networks in Europe. We have connections all over the world. We’re a very capable partner whether that’s going to be with the E.U., or

with the new American administration, which I’m very enthusiastic about, and to change the approach of the last few years, and be more globally

engaged, and Britain will be a great partner for them to.

AMANPOUR: Yes, I mean, that sounds great.

But your own wife, who’s in the fashion industry, which is a major part of the British economy, has said that her business faces difficult challenges.

We have heard from major British fashion designers that the government has not even talked to them about how to actually continue this industry, which

is huge.

And, as I mentioned, the financial services did not get a deal…

CAMERON: No.

AMANPOUR: … in this deal to leave the E.U.

As “The New York Times” put it: “Even those who can reach European markets” — this is exporters — “have discovered that the promise bonfire of

regulations is actually a burning hell of paperwork.”

Do you think, like your successor, Boris Johnson, says, that these are just teething problems, or is there more problems at the heart of this?

CAMERON: As I have said, I think it’s a mixture of some things that can be ironed out, because they were unintentional.

But I think some of the things relate directly to the fact that we have chosen to leave the single market. And, yes, of course, being married to a

fashion designer who’s running a fashion label, wants to export all over the world, including to the E.U., I have a daily reminder of those

difficulties, because it has become harder.

But we have to make it work as best we can. I think the experience of Switzerland and other countries outside the E.U. is that you never, in some

ways, stop negotiating, because there are always new things, whether it’s financial services or other services, or the access, for instance, to the

E.U. for artists and musicians and others, there are more things to negotiate.

And there always will be, because, ultimately, the biggest market that the U.K. has is the 350 million people on our doorstep in the E.U. single

market.

The reason I make the point about Britain being the fifth or sixth largest economy in the world is, I think that’s important, because we are a

worthwhile and important partner to the E.U. If we were much smaller, I would be even more worried about what the future would hold. But I think we

are big enough to try to make the best of this new situation.

It’s not the one I recommended. I recommended staying in the single market, staying in the E.U. on amended terms. But we made our choice. Now we have

got to make this work. And the government have my support as they tried to do that.

AMANPOUR: Even though, as the polls show now, the majority of Brits actually don’t support and wish that it hadn’t happened.

But be that as it may, as you say, I guess made you bed, you have got to lie in it now.

CAMERON: Opinion polls told me lots of things in my political life.

AMANPOUR: Right.

CAMERON: They told — kept telling me I was going to lose elections that I won and win referendums that I lost.

So, while I don’t denigrate them completely, like farmers and the weather forecasts, they’re all we have got to go on.

AMANPOUR: I want to ask you two rapid-fire questions.

So, these are kind of yes-and-no answers. We have talked about the budget having been reduced. Are you lobbying? Would you lobby this current

government to raise the budget to where you had it, at 0.7 percent foreign aid?

CAMERON: Yes. I would stick to 0.7 percent.

The truth is, because our economies has got smaller, because of COVID, there was a cut coming in the aid budget anyway, because it was to be 0.7

percent of a smaller economy.

So I think to go ahead and cut it further was a mistake. I hope, even at this late stage, they can be persuaded to think again, not just because of

the great moral force that brings, the good it does, the hungry it feeds, the vaccinations it delivers, the children’s lives it saves, the people it

educates, an amazing force for good, but it’s also a great force for Britain in the world.

The fact that we made a promise of 0.7, we kept that promise, is an enormous aspect of U.K. soft power. It shows what an engaged and force for

good we can be in the world.

AMANPOUR: And another…

CAMERON: Sorry. That wasn’t a yes — but it was a yes-or-no answer. I — but I then added to it a bit.

AMANPOUR: You did.

Now, how about this as a yes-or-no final question? Yes or no, vaccine passports for the U.K., and potentially green passes, like are being

discussed in Israel, for domestic use of jobs and stadiums and the like?

CAMERON: Yes, I’m not against it.

I mean, ultimately, we do have to have — there are certain vaccinations and things we’re encouraged to have when we’re children that are almost

compulsory. If we want to open up our economy as rapidly as possible, I think there will be a number of different ways and places where people will

want to know, have you been vaccinated before you join this event, this party, this whatever?

So, I think it’s coming. And I’m very glad that the government is having a serious think about all the money moral and ethical and legal dilemmas.

They should not close their mind to this. I haven’t come up with the answer, but they definitely should keep an open mind and have a good look,

because we have got to try and get back to normal.

And normal is going to mean as many people getting vaccinated as possible.

AMANPOUR: Prime Minister David Cameron…

CAMERON: I’m looking forward to getting mine.

AMANPOUR: Yes. I’m looking forward to getting mine.

(CROSSTALK)

CAMERON: I have got a bit of time to wait, but full credit to the government for a very successful vaccination program that is running well

ahead of anyone else in Europe and is almost — apart from Israel — is one of the best in the world.

AMANPOUR: Spoken like a British prime minister.

Thank you for joining us, David Cameron.

CAMERON: My pleasure.

And now from the family of nations to a big question: Who is your family? The people you are genetically related to? The people you grow up with? And

what if your idea of family and identity was turned completely upside down?

Technology correspondent Samuel Burke has investigated all of this in a new podcast series called “Suddenly Family.” He got into it after a shocking

DNA discovery of his own. The series was produced in partnership with CNN affiliate network CNN Philippines

Have a look at the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Unbelievable. Oh, my God. That’s the worst thing I have ever heard about my family.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I think she had a hand in my father’s death.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Well, I get emotional. Sorry. I can’t imagine what she went through.

SAMUEL BURKE, CNN BUSINESS AND TECHNOLOGY CORRESPONDENT: On my new series, you will listen in on families like mine, trying to solve our mystery DNA,

and put our lives back together after a simple swab of the cheek robbed us of everything we thought was true.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: I went from having three blood relatives to over 1,600 overnight.

(LAUGHTER)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: That’s a laugh. And we will be digging into that with Samuel Burke, who’s joining us now.

Samuel, let me first start asking you. We heard that laughter at the end of that trailer there. But you have talked also about some of the more

shocking, some of the darker sides of DNA discoveries.

BURKE: I think what really ripped a layer off for me is that you see all of these ads, so much marketing from the DNA industry showing that this is

a happy, joyous occasion when your results come in.

But there’s this other side. Eleven percent of people who take a DNA test find out that one of their parents isn’t their biological parent. And that

seemed ridiculous to me when I heard that number, until it happened twice in my own family.

And so there’s really not a lot of laughter as you try to solve your mystery DNA, make some huge realizations. Really, your whole world can be

turned upside down. Who you are can be rewritten by this technology, at- home DNA testing.

AMANPOUR: So, let’s talk about your family.

I mean, it is actually episode four. But it is what, as you say, brought you into this investigation. It’s about your father, right, and your

grandfather. What happened in their investigation?

BURKE: Well, I come from a Jewish Dutch family on my father’s side,. Very proud to be Jewish and Dutch.

And when we get the DNA results back, right away, my father is incredibly upset, because it comes back half-Jewish, as we’d expect from his mom’s

side, but half-Swedish. And that just makes no sense to us. There are no Swedes and our family. And the DNA test also says that we’re Mormon. And

it’s a big surprise for a Jewish family to see Mormon.

And, of course, Mormon is a religion. You expect an ethno-religious group like Jews to show up on your DNA test, but not a new proselytizing religion

like Mormons that take people from all different parts of the world.

And so, very quickly, my dad knew that something was off. Now, I didn’t agree with him. I said, oh, well, maybe Sweden is close to Holland. Maybe

we had some ancestors who went back and forth. But the more we looked, we saw that there were no Burkes on our DNA test, not a single Burke. And my

last name is Burke. My dad’s last name is Burke.

And we really started realizing that his father was likely not his father, and we were related to all these Mormons instead. And it was a very dark

period to go through, my dad realizing that the man who raised him, the man who he thought he looked like he was not his father biologically, and that

we had this whole other history and a secret in the family that nobody had any idea about.

AMANPOUR: So, before we get to you revealing the secret and how you got to know, let’s just play a little clip about this revelation. This is you.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

BURKE: I start looking for photos of this stranger. And when I find a photograph of him, everything stops for a moment. I will never forget it,

because I knew my family’s life would never be the same.

Right away, I see both my dad and his brother in this man. I see my dad’s mouth. I see my uncle Bill’s eyes. I even recognize some of myself in this

picture.

And as I read more about Roland Perks (ph), I see his family is of mainly Swedish heritage. And it finally all comes together. The man who raised my

dad and uncle Bill was not their biological father.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: So, Samuel, two questions. Who was this man who raised them, and how did the mixup happen? And how have your — how has your father, your

uncle, how has your family reacted in the aftermath of this knowledge?

BURKE: Well, it depends who you ask.

The man who raised my dad and my uncle Bill was their dad, but he wasn’t their biological father. The way my dad and I look at it, it looks like my

grandparents were one of the first couples in Arizona to use artificial insemination.

But if you ask my uncle, he doesn’t come to the same conclusion. And that’s part of the difficulty of this. DNA tests promise to give you all the

answers, but, really, they can create many more questions. And my uncle was wondering, was there somebody else in my grandmother’s life? Did they use

actually artificial insemination? Or did they have a friend who helped them out?

We don’t get the answers because these people aren’t alive anymore. They took the secret to the grave. And, as I went through this, the journalist

in me really wanted to get the answers and move as quickly as possible.

But as I hit the moment that you just played, I realize that it upended my father’s life. And it was supposed to be a happy ending, like the DNA tests

we show. But my dad didn’t get to meet his biological father. He had died just a couple of years before we made this discovery. And even more

heartbreaking, my dad found out that he had a half-brother who had actually taken his life just a couple of months before we made this discovery.

And it was really gut-wrenching for me to know that, in a way, I took a part of my dad’s father, my grandfather, away from him, that he wasn’t his

biological father, and that my dad didn’t get to have the happy ending, meeting another sibling.

And I really came to regret buying my dad the DNA test, because he would have just gone along his life thinking this other story that he had been

told and had lived was the true story.

AMANPOUR: So, that really raises a huge number of issues there, that, on the one hand, you want to know. On the other hand, the consequences can be

so dire.

I think that, in the interest of full disclosure, you are part of the CNN family. You were this program’s first social media producer, and then you

became tech and business correspondent. And now you have launched your own investigative and podcast series in this respect right now.

And I think it’s fascinating, because you don’t only look into your own family. You have gone also — you have one episode called “The Girl Next

Door.”

Tell us about Ana. I’m going to play a little clip, and then you can tell us about this story, because, again, it’s about secrets and lies, and not

knowing finally what they’re going to find out.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: I just wept. And I — even thinking about it now, it’s still — it’s painful. It’s sad, it’s so hurtful that someone just

couldn’t — could somebody have not even left me a note?

It’s so painful, because I don’t personally want to live in the rearview mirror, but I have put myself in the rearview mirror, because I need to

make sense of a lot of things so I can continue to move forward at this point.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, Samuel, in short, this is your first episode. And this is a girl, a woman whose mother, in fact, had an affair with the next-door

neighbor.

Explain the rest of the story and how they are now.

BURKE: Well, the part that is so difficult about all this isn’t just the proximity for Ana, the woman in the podcast. It’s that her best friend her

whole life is the girl next door, the daughter of who she finds out to be her biological father.

I mean, Christiane, imagine taking a DNA test and finding out that your best friend is your half-sister. Her dad was having an affair with your

mom. And I think what’s so mind-blowing about Ana’s story is that everybody knew except for Ana.

When she goes and starts telling people, everybody is very unsurprised. They think this is totally logical. She doesn’t look like the people in her

family. She looks like her neighbor. She looks like her best friend.

But it’s something much deeper than all this, because Ana has had this disconnect her entire life. She’s always known that something was off.

People in her family treated her like the bastard child. Those are her words, not mine.

But she never could put her finger on it. Why am I treated different? Why do people look at me differently? Why does my mom’s family — even though

her mom had the affair, why does my mom’s family treat me differently? And only when she gets the DNA result does it come together.

But the proximity of it all, and the twisted nature of it and the fact that her mom never told her, even though she had all of these question marks,

really puts into question her whole relationship with her mom who is no longer around. And so, you are to rebuild these relationships with people

who are not even on earth anymore and, of course, take your best friend, tell her the truth, say, well, all the people on my DNA test have your last

name and try to build the sisterhood, which, thankfully for Ana and her best friend half-sister is exactly what they do.

AMANPOUR: Well, that’s — again, that’s a beautiful ending to that very sad story. And as you say, you know, lot of people who find out their

secrets don’t want to admit them, that there have been extramarital affairs or whatever, as is in this case. Here’s an incredible statistic. 11 percent

of the people who take these DNA tests discover one of the parents is not their biological parent.

What sort of reaction have you had since this series has dropped? Now that all of the people you have talked to have seen how you produce the series

and have seen each other’s stories as well or will be as they drop?

BURKE: Well, that number that you just stated, which is from a scientific study, seemed ridiculous to me, Christiane. 11 percent of people finding

out that one of their parents is not their biological parent? But then it happened twice in my family. My dad had the result that we’ve talked about.

But my mom also discovered a sister that she didn’t know about. And my new aunt, she found out that her father was not her biological father, and that

my mom’s dad was her father.

And I think what’s been most incredible about going on the DNA journey is that no matter where I go and now that the series has launched, everybody

seems to have one of these shocking results. Now, of course, I was your producer for a long time and you and I were at dinner one time and I was

telling you about this DNA discovery in my family as it was happening, and one of the people in the podcast is a woman who was sitting next to us at

dinner who heard my loud voice talking about this DNA result came over and shared her shocking DNA result.

And my point in telling you that is that no matter where you go, whether you publish a podcast or you have a discussion over dinner about your DNA,

your heritage, your family secrets there is somebody sitting right next to you who is experiencing this. The DNA industry makes it look like it’s all

a lot of fun, but huge swathes of people are having their lives completely rewritten by this technology.

And I think for me, having covered technology for so long, I have started to realize more and more that social media and so many parts of the other

parts of technology, including the at home DNA testing, are completely changing our lives. If we didn’t have these tests, if we didn’t have

Twitter or Facebook, which you know that I championed so much, you know, our lives would be incredibly different. That day at the capitol would have

looked incredibly different. My life, my dad’s life would have looked incredibly different.

Technology is changing our world in ways that I don’t think we could have ever seen coming. And I think it’s getting worse and worse.

AMANPOUR: Well, let me then finally ask you, because, you know, there’s a lot to be said for finding these secrets out. But now, there is a lot to be

said also about protecting privacy. That story you tell about the restaurant is — you know, I mean, you know, the — nothing is private

anymore in the world. But 23andMe, one of these operations, is apparently going to be acquired or going into the deal with the Branson Acquisition

Group, and there are concerns about what happens to all this genetic data and information.

Just quick in the 30 seconds we’ve got left, is that a worry?

BURKE: Oh, it’s absolutely a worry. But what I always tell people is we can’t even have this discussion because people say, well, what are the

terms of service? As soon as one of these companies, like 23andMe, which is valued at $3.5 billion is acquired by another company, all of the

agreements change. What you signed changes. Your DNA goes into other people’s hands. And so, there is nothing even to discuss because we don’t

know what is happening. And so, that’s I am focused instead on what I know for sure that our lives, our heritages, our families are suddenly changing

with these tests.

AMANPOUR: And Suddenly Family, and this is your podcast series. Samuel, thank you for joining us.

And now, we’re going to revisit our reporting of the coronavirus pandemic. Russia’s vaccine diplomacy with its Sputnik V has become one of the most

preordered of all the vaccines in the world after being proven safe and effective. And at least 30 countries have signed up.

But the vaccine has received a somewhat a chillier reception at home. Correspondent Matthew Chance got exclusive access to one of Russia’s new

vaccine manufacturing factories.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MATTHEW CHANCE, CNN CORRESPONDENT: The site was once a cold war biological weapons center. Secret, remote and closed. But CNN has gained exclusive

access to the high-tech facility where Russia now makes Sputnik V. It is controversial but effective COVID-19 vaccine.

The next important part is to get the pure and clean sterile water.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Right.

CHANCE: Every step in the largescale process had to be carefully calibrated, the chief scientist tells me. Delaying mass production of

Sputnik V, approved in August last year until now.

And have you already made that step? Are you already now producing millions of vaccines, millions of doses every month?

DMITRY POTERYAEV, CHIEF SCIENCE OFFICER, GENERIUM PHARMACEUTICAL: Yes, we are producing several millions of vaccines every month. And we are hoping

soon to get even a higher amount, maybe like 10 or 20 million per month.

CHANCE: With those numbers, Russian officials now say any healthy adult here who wants Sputnik V can have it. Opening up pop-up clinics like this

one in a Moscow mall, encouraging shopped to get vaccinated, offering a free ice-cream with every jab to sweeten the deal. Even the secretive

Russian lab that pioneered Sputnik V has opened its doors, offering the vaccine directly as it were from the source.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Roll up.

CHANCE: OK. I am rolling up. Like I am not that nervous about having the Russian vaccine, because — I am really not, because, you know, it has had

large scale clinical trials and it has been peer reviewed in a major journal and it’s been found to be very safe and 91.6 percent effective,

which is very good. Anyway. it is too late now, because it has been done. The interesting thing though is the fact that I can get a vaccine here in

Russia at all given that I’m not in a vulnerable category.

Fact is, the county with one of the world’s highest number s of COVID-19 infections also has one of its highest vaccine hesitancy rates, fewer than

40 percent willing to have the jab according to one recent opinion poll. You’d Vladimir Putin would step forward to allay public fears but unlike

many other world leaders, the Russian president has yet to take the plunge. Kremlin says it will announce when a presidential vaccination takes place.

But in a country that looks to its strong man for the lead, his vaccine hesitancy is doing nothing to bolster confidence.

POTERYAEV: The boxed and labeled vaccine is stored before being distributed to the patient.

CHANCE: And this is how the distribution. How many doses in this box?

Still, more than 50 countries have now ordered Sputnik V according to the RDIF, Russia’s sovereign wealth fund. Russians may still be shunning their

vaccine —

So, the same boxes are going to Argentina, Brazil and other countries?

POTERYAEV: Right. Wherever it goes in the world.

CHANCE: But global demand for Sputnik V continues to surge.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, let’s look at a different aspect of the public health response with Harvard University epidemiologist, Julia Marcus. Here she is

talking to our Hari Sreenivasan about how we can mitigate the risk of COVID in a sustainable way.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

HARI SREENIVASAN: Christiane, thanks. Dr. Julia Marcus, thanks for joining us.

First, I want to ask you about a series of articles that you wrote for at “The Atlantic.” And one of those first ones was a very simple idea, risk is

not binary. Explain that.

JULIA MARCUS, INFECTIOUS DISEASE EPIDEMIOLOGIST, HARVARD UNIVERSITY: Yes, the risk is a continuum. And I think at the time when I wrote the article,

which is back in May, it felt like we were stuck in this binary discussion about whether we were going to stay locked down forever or go back to

business as usual. And of course, neither of those options was really feasible and there is a lot in between. And I wanted to draw attention to

the in between area and really start to help people think about risk as a probability rather than, you know, this dichotomy.

SREENIVASAN: Because it’s easier for people to kind of grasp that dichotomy, it seems that anything in between seems like a compromise that

one or both sides won’t accept, right? I mean, the people who are concerned for their health says, well, there is a risk. And look, we have nearly

500,000 Americans dead from this. So, we’ve got to take precautions. And then you’ve got folks on the other side who are like, well, this isn’t that

relevant to me or my immediate community.

MARCUS: Right. And I think that as is often the case, the truth is somewhere in between, and you are right, that nobody is going to be happy

with any particular approach, but I think we need to accept that, yes, this is a huge problem that we need to address and we need to take on as many

risk mitigation strategies as we can, but we also need to think about what the tradeoffs are for each of those. And there are always tradeoffs.

You know, we could potentially eliminate risks in some scenario where humans could remain completely isolated for some time, but that’s just not

possible. So, what is it that we can do that’s realistic and is going to be sustainable for the long-term, which as it’s turned out, this really has

become quite a long-term situation.

SREENIVASAN: Because as we have seen, isolation comes with several hidden costs.

MARCUS: That is right. There are costs of isolation, there are also people who continue to go to work. And we need to think about, you know, who are

the people who we can pay to stay home. And for those who we can’t, because society needs to continue to function to some extent, how do we protect

those people?

So, you know, assuming that we can eliminate the risks kind of ignores some the ways that society needs to continue to function, that humans have to

interact to some extent for us to continue to survive. And then, yes, there are mental health costs of isolation as well, and for — especially for,

you know, elderly people who are isolated in nursing homes, you know, there are a lot of different scenarios that we can think of where there really

are some large costs to maintaining safety over some — you know, some semblance of well-being.

SREENIVASAN: So, how do we reduce it? I mean, if we can’t get to zero, how do we minimize it knowing that some people are going to have to take risks

because of the jobs they do, the roles they play in society or even their own families?

MARCUS: I think what can help is really focusing on where risks really are. And I don’t know if we have always done that during the pandemic. I

think we’ve gotten distracted by the things that really visible, like the people being outdoors without masks, you know, people gathering in the

parks. But actually, most of the risk is indoors and most of it is happening in the workplaces and in people’s crowded households.

And so, how do you make those situations safer? How do we ensure that people have safe places to isolate away from their crowded households? How

do we ensure that people can stay home from work when they’re sick and make sure that people are able to afford to do the things that we are asking

them to do to reduce risks?

SREENIVASAN: What is the role of politics and policy and government? Because in some ways, I feel like the onus has been put on the individuals

where there are definitely systemic and structural things that only collective organizations like communities and governments can perform.

MARCUS: I think there has been a lot of emphasis during the pandemic on personal responsibility, which, of course, is important especially in an

infectious disease epidemic where risk affects not just you, but the people around you. But there is a lot more that needs to be addressed here to make

progress. It is not just, you know, if everybody wore a mask for four weeks, the virus would go away, and that is the kind of the messaging we

were hearing months ago. It’s — but people continue to have to go to work when they are sick, because they can’t afford to stay home. It’s that

people having to wear it to isolate.

And so, everybody in their household, including the older generation gets infected as well. And these are problems that have not been addressed.

There was an emergency paid sick leave measure that applied to only about half the workforce and has expired, you know.

So, we haven’t really taken the steps that we need to, to really address what is driving risk and those structural factors, in particular, which I

think is so obvious in terms of who has been affected by the pandemic, in terms of not just caseload and mortality, and it is worldwide. I mean, the

working and living conditions being associated with these outcomes is a worldwide phenomenon.

So, policies can solve those problems, individuals cannot.

SREENIVASAN: How much of this comes down to how we message or how we communicate this? Because, in the beginning, it seemed is like fear was one

of the driving tools trying to communicate this, but there seems to be a diminishing marginal turn to how long we can stay afraid.

MARCUS: Yes. I think fear is a bit fraught in terms of a public health messaging strategy. I think it can have an impact of people’s behavior, but

I think it does tend to be short-term and it can come with some costs as well.

And I think, as you’re saying, we really did have a massive shift in behavior, that first month to two months when the stay-at-home orders

rolled out in March, in April. But that level of fear and massive behavior change cannot be sustained indefinitely. And I do want to recognize that,

in fact, people have continued to, you know, change their behavior over time, but that people also have to continue to live their lives to some

extent.

And public health messaging, I think, does better when it comes from a place of compassion and giving people as much information as they need to

empower them so that they can make, you know, informed decisions in their everyday lives.

That said, public health messaging, when it is good, it is necessary, but it is not sufficient. You actually have to give people the resources they

need to take the steps that you want them to.

SREENIVASAN: You know, very quickly after that first month or so, people, when they saw (INAUDIBLE) behavior, whether it’s parties in spring break in

Florida, et cetera, there seemed to be a shift where it’s almost a shaming, a moral nature that crept into how we perceived behaviors by other people.

MARCUS: Yes. And of course, there is a moral nature to this, as we’ve talked about, you know, the risk isn’t just to yourself, it’s to other

people and that does bring in a layer of morality and ethics. But I think what — when we think about what works as public health messaging and what

works in terms of, you know, the way that the public interacts with each other, shaming does not tend have the effects that we want it to have, and

we have seen this in other areas of health.

I work on HIV prevention, but we also see it in substance abuse and other areas of health where when you shame people, you tend to drive them away

from public health effort, and we are seeing that now with the people who are afraid to get tested because they don’t want to be judged, they don’t

want to tell people that they have been exposed or that they may have exposed somebody else. And you can see how that start to breakdown to

public health efforts, especially the contact tracing.

And so, what works better is really trying to recognize why people are taking risks. And sometimes the things that we’re shaming people for are

really not very risky like hanging out in the beach, sometimes they are quite risky like having a big indoor party. But the goal is to reduce

infections and maximize health. Let’s ask why are people having a party and what can we do to help them meet their needs in a safer way. And the need

is not to have a party, the need is to stay socially active.

So, how do we encourage that? Do we create spaces outdoors where people can gather more safely and encourage them to gather there? I think really

thinking creatively about how we can address what it is that’s driving that behavior will be more productive than shaming a behavioral result (ph).

SREENIVASAN: We must have evidence over time through different campaigns that just saying, don’t do it, just saying, no, doesn’t work.

MARCUS: Yes, the just say no approach has been a failure in many areas of health. And I think we can think of a few, teen pregnancy, substance use,

HIV prevention, it just doesn’t work. And the reason it doesn’t work is that people have reasons why they take risks. And the just say no approach

assumes that people can eliminate risks and it ignored the concept of people’s lives and the other aspects of health that may be sacrificed when

they don’t take those risks.

So, let’s take teen pregnancy for a minute. If we tell teens just say no, what’s going to happen is that some of them are going to have sex and

they’re not going to have the tools that they need to reduce risks when they do. So, in fact, we have missed an opportunity to give the people

information and tools that they need to reduce the risks when some of them do inevitably take those risks. And we also ignored the context that drives

people’s risks and people’s decision-making, and sometimes that context include structural factors that are out of their control, and that’s very

much the case during the COVID pandemic and certainly with HIV as well, that, you know, working and living conditions are some of the main drivers

of risk.

And when we think about risk as being driven by individual choices, we miss that context and we miss opportunities to help people reduce them.

SREENIVASAN: So, what have we learned them from, say, for example, your work with HIV/aids and the prep pills? What have we learned from that that

we can apply to behavioral modification or encouragement in this case?

MARCUS: Yes. I think we’ve learned a couple of key things. One is about how we message. And I think what we learned in the aids epidemic, we went

from messaging in the early days that was really based in fear and shame to now messaging that’s based in what really matters to people about sex,

which is how — you know, when we think about sexual transmission of HIV, people get HIV it in context of something that they are enjoying, that’s

about pleasure and intimacy. And now, our messaging really centers that, because we understand that we need to center what matters to people.

And secondly, I think equity is a huge lesson that we have learned from HIV epidemic, thinking about the structural factors that drives people’s risks

that actually need to be addressed before people can reduce risk. PrEP is, you know, a daily pill to prevent HIV and that’s my main area of research.

It’s been around for almost a decade, and we see limited population impact. And there are many reasons why people cannot access it.

And that’s the kind of think we need to be thinking about during the COVID pandemic. It’s not just stay home, it’s how do we give people the resources

that they need to stay home. And thinking about that, you know, taking that lenses with every single intervention that we are thinking about and

ensuring that the highest risk people are able to access those intervention is going to be fastest way to have a population change.

SREENIVASAN: You know, there seem to be parallels here when you’re talking about the PrEP pill and when we’re thinking about the vaccines right now.

When those pills first came out, was there concern that people would engage in a more risky behavior because they felt like they now they had an extra

shield of protection? I mean, did that play out that way?

MARCUS: I would say that was actually the dominating conversation at the time and this was in 2012, when PrEP was first approved by the FDA. And

there was really — you know, rather than a celebratory atmosphere around this amazing biomedical intervention, which by the way is much more

effective than condoms in reducing HIV transmission, there was kind of a hesitancy and a lot of hand wringing about how it might create, you know,

promote promiscuity and condomless sex and that we were going to see a breakdown of HIV prevention particularly for gay men for — you know, for

whom this was going to be a boon after decades of condoms being the main stay of HIV prevention.

And I think that has slowed the uptake. And we still see today that some health care providers are reluctant to prescribe PrEP or will not prescribe

it because they have concerns about people changing their behavior. And I think we’ve seen some of those themes play out around the vaccines that we

know are extremely effective in preventing people from getting get sick from COVID and also, we’re starting to see that they are going to reduce

transmission as well to some extent.

And so, you know, the — that is something to celebrate, but I think we’ve seen a lot of cautious messaging that may actually deter people

inadvertently from getting vaccines.

SREENIVASAN: So, what is an example of positive way to message that’s — that kind of toes the line between forceful and appropriate? How do you get

these things across because different people react to different types of data?

MARCUS: Well, just as an example, with the vaccines, in particular, you know, we can think about how we can tell people that their risk of disease

is vastly reduced, and that when they are spending time with other people, there is still a possibility that they could carry the virus but — and

transmit it, but we know that that is also reduced to some extent as well even as we learn about it.

I think one thing that we need to distinguish is between public and private settings. So, for now, until more people are vaccinated, we do need to keep

up precautions in public setting including masks and distancing, even vaccinated people and that’s because we can’t really determine in public

settings who’s been vaccinated, who is vulnerable.

But as more are vaccinated, that will change. And in people personal lives, you know, the questions that we’ve hearing are, I am a grandparent, I’m now

vaccinated. Can I hug any grandkids? I think we need to be clear that the risk is vastly reduced of having a bad outcome, particularly, you know,

severe disease, hospitalization or death, we really have seen that happen very rarely among people who are vaccinated.

But there is a small chance that somebody who is vaccinated could transmit the virus to somebody else. And that’s the thing we can communicate and

people can then make decisions accordingly.

SREENIVASAN: It seems like if we pivoted toward the opportunity of what lies ahead if we take these steps versus the costs that are all around us

and behind us, I mean, I don’t know, does optimism work better? I mean, if I am saying is, hey, I kind of want to enjoy life again. That is why I want

to get this vaccine.

MARCUS: Right. And people have different motivations for getting vaccinated but that is a big one for people like, you know, getting back to

some semblance of normalcy, being able to be close to loved ones. And I think, again, going back to that example about PrEP and HIV prevention

messaging and how we now know that we need to center what matters to people and use the positive messaging rather than fear and shame, the same kind

applies here where I think we recognize what is it that matters to people? Well, you know, there being much lower risk of getting very sick. That

matters to people. And also, being able to be closer to other people with lower risk. That matters to people, too.

And so, I think including a kind of all of these motivations in our messaging in such a way that people see, OK, this is a tool that is going

to get me where I want to be. I think that is going to be an effective approach.

SREENIVASAN: Dr. Julia Marcus, thanks so much for your time.

MARCUS: Thanks for having me.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Positive messaging indeed.

And finally, tonight, we remember the influential poet, publisher and iconoclast, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who has died this week just amongst shy

of his 102nd birthday from his iconic city lights book store in San Francisco. Ferlinghetti inspired generations of avant-garde poets and

writers.

In 1996, he published Allen Ginsberg’s beat poet “Howl.” He was hit with obscenity charges as a result but he beat that wrap and he struck a major

blow against censorship in the process. Ferlinghetti inspired musicians as diverse as Bob Dylan and Cyndi Lauper. And his influence on poetry survives

today even at the January inauguration of President Joe Biden. Here he is reading an excerpt from his much-loved poem collection, “Coney Island of

the Mind.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LAWRENCE FERLINGHETTI, POET: The world is a beautiful place to be born into, if you don’t mind happiness not always being so very much fun. If you

don’t mind a touch of hell now and then, just when everything else is fine, because even in heaven, they don’t sing all of the time.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Remembering poetry. That is it for now. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.

END