Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

Deadly protests rocked Baghdad with one year until America’s election, we dive into a foreign policy issue that’s plagued U.S. presidents for

decades, Iraq.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JULIE ANDREWS, AUTHOR, “HOME WORK”: I was gob smacked and said, oh, Mr. Disney, I would love to. But I’m so sorry, I’m pregnant.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: From “Mary Poppins” —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREWS: It’s supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: — to Maria Von Trapp and much more, national treasure, Julie Andrews, reflects on the ups and downs of her dazzling career.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

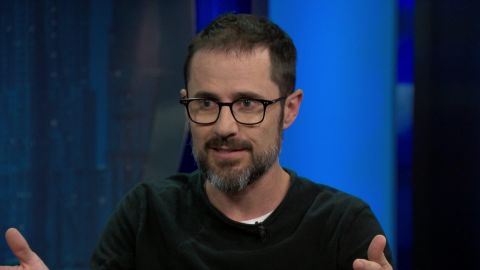

EV WILLIAMS, CO-FOUNDER, TWITTER: It turns out there aren’t enough actors in the world to wreak a lot of havoc.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Twitter’s toxic side. Our Walter Isaacson challenges company co-founder, Ev Williams, on how to reign in the madness.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

The countdown is onto the U.S. presidential election. Yes, a year from now, the American people will go to the polls and they’ll choose whether to

keep President Trump in office or to replace him.

With all the impeachment news on the domestic front, it is easy to lose sight of critical issues that are going on beyond the borders. One such

example, Iraq, where the United States is heavily invested and where American presidents have struggled for decades.

Of course, President Bush invaded back in 2003 and the country is still wounded by war and divisions. But after two years of relative stability,

deadly protests seem to have suddenly erupted in Baghdad in the biggest wave of demonstrations since the fall of Saddam Hussein. More than 200

people have been killed in the last month. Protesters are angry at their leaders, who they say are corrupt around failing them. They are also angry

at outside influence in Iraq especially from Iran.

Now, the Iraqi prime minister, Adil Abdul-Mahdi, offered to resign but he hasn’t done so yet.

To understand what is powering these protest movements and tear impact on the region, I am joined by Vali Nasr, he’s one of the world’s leading

authorities on the Middle East and a former State Department official. And here in the studio, Karl Sharro, an architect by trade. Sharro is gaining

fame or so as an astute politics and culture in his twin homelands Iraq and Lebanon. He is the man behind the “Karl reMarks” blog.

So, gentleman, welcome to you both.

Vali, let me ask you the big picture question. I said it seems to have suddenly erupted in Iraq but maybe that’s because we haven’t been paying

attention with all the other street protests. But what is surprising you about what’s happening in Iraq?

VALI NASR, PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY: First of all, you’re right. It’s not new. There were — they have

protests in Basra and also the Iranian consulate that was burned over a year ago.

I think what’s surprising is that, first of all, that it’s happening with the ferocity that it is, that, you know, the protests are much larger, the

protesters don’t seem to be going the way that is becoming much more contentious. Secondly, that it is so easily directed at Iran and the

militia as they’re actually fought alongside with Iran against ISIS. That the militias that were sort of greeted as heroes or the commander of Iran’s

force, General Soleimani, that was treated as a hero for pushing back the ISIS pressure on Baghdad, Karbala and Najaf are now seen as villains.

And I think that’s a very interesting turn. At one level, it suggests that the problems that people are facing are really deep, that the knife has

really hit the bone. At another level, it also suggests that the fear of ISIS the siege that ISIS has brought to Iraq is been lifted, that the

population is back to asking for bread and butter issues and they don’t feel that they have any debt to pay to Iran or to its militias and are

holding them to task.

And I think the U.S. absence from all of this is finally — the other surprising thing. This is the first time that the United States really

clearly looks disinterested in. Even though this prime minister was a choice that the United States and U.S. stands to lose a lot if everything

unravels in Iraq, it doesn’t like look like U.S. is engaging at all.

AMANPOUR: That is so interesting. And let me get to you now, Karl, from sort of a street and granular level, because, first of all, you come from

that part of the world and you are engaging with people on your Twitter and “Karl reMarks” blog. What are they saying and how are they engaging with

you about what exactly is causing these protests, whether in Lebanon or Iraq?

KARL SHARRO, SATIRIST: Well, I think — you know, I come from a generation that we had our own protests in the past, but nothing on this scale. And

if you had asked me, you know, years ago, would you have expected something like this to happen in Iraq today, I would have said, definitely

no.

What I observe and what I hear from (INAUDIBLE) is the levels spontaneous anger. This is not the traditional parties. This is not the traditional

movements, both in Lebanon and Iraq. The situation has got to an extension, almost level of impasse, that the people find no other outlet

except resorting to the street and at a much bloodier level in Iraq because of the repression, much higher casualty levels, you can see people are

willing to go day after day. And we need to ask ourselves why.

And I think a lot of people in the aftermath — as Vali rightly pointed out, in the aftermath of defeat of ISIS, they thought there was going to be

a period of honeymoon. And obviously, that wasn’t the case.

AMANPOUR: So, the peace dividends that never came?

SHARRO: Exactly, exactly. And the chief reason for that in both contexts is the incompetence of the political elites. The lack of any economic

vision. The levels of corruption, endemic corruption, as the squandering of the public person, public assets.

And I think this is leaving people, you know, marginalized to the extent I have only two choices, do I immigrate or do I try to make my country a

better place? And what we are seeing today a resounding yes to trying to make the country a better place. It’s not polished. It’s not formed. It

will get there, I think, in time. But what we’re seeing is the first manifestation of anger that has been building up over the years.

AMANPOUR: See, I think that’s really interesting, the sort of silver lining you are saying. It’s actually the first manifestation of people

wanting to own their countries and not wanting to flee.

Now, in Lebanon, as we know, the prime minister resigned. And in Iraq, Vali, the prime minister has offered to resign but hasn’t done it yet.

We’ve had a former prime minister whose come out and said that actually he should be listening to the people. We had the president of Iraq, Barham

Salih, who is saying in so many words that the prime minister should be listening to the people and listening to the protesters.

What do you make of the idea that — you know, this peace dividend, they hadn’t seen it yet, which you raised, but also that this might be almost

kind of a hopeful turn, maybe an Arab Spring 2.0?

NASR: Well, it is actually Arab Spring 2.0. I mean, the issues that Arab Spring 2.1 raised were never really resolved. And even in Iraq, there were

street demonstration during the first Arab Spring and they didn’t get anywhere. I think the young population and the population as a whole are

frustrated. They still want dignity. They want jobs. They want better government. They don’t want corruption.

But the problem they are facing is that is the problem that people in Egypt or in Bahrain faced in the first Arab Spring. In other words, the protest

is genuine. It’s very powerful. It will force the government to concede, but it’s not very clear that where do you go from here? In other words, if

Prime Minister Adil Abdul-Mahdi were to resign and elections were held, what would come after? How do you put back a government together,

particularly because in Iraq it’s very difficult to do?

So, some of those issues are there. There is not an easy exit ramp here, particularly in Iraq, as to how do you create better government. And I do

think that right — we have the best opportunity now that the political class is scared, that is a bit shell shocked, that it may be open to making

serious concessions in form of changing the electoral law, perhaps revisions to the constitution, which would dampen some of the sectarian

divisions.

But as I said, this is only — the hopeful moment has to, yet, translate into something concrete if it’s going to get there.

AMANPOUR: Well, I mean, you know, you put your finger on the pulse because actually, the prime minister of Lebanon, as we said, did resign and people

are still on the streets and they’re saying everybody means everybody. I mean, they want everybody out. But I also want to pick up with both of you

this idea of sectarianism because I think people in both countries are fed up with it, that constitutionally, and you know better than I do, Karl,

people are saying that why should there be, you know, these concession made just because somebody is from one confession or another.

And, in fact, you know, you have written about this. Iraq’s politics, you say, were modeled to resemble those of Lebanon’s, or to remodel, various

cause to consider similar arrangements in Syria. It’s the struggle of the secular vision against the hegemony of the federation of sects will

continue to inspire. But the secular version’s lack of success so far should be a warning about the power of identity-based politics. The

revival of universalist ideals is an urgent task today.

Do you think, Karl, that it is even possible in Lebanon to get away from these sects and the handing out of various positions, depending on whether

they are Christian or Sunni Shiites or Jews?

SHARRO: I mean, I am very optimistic and positive today. When I wrote that three or five months ago, I wouldn’t imagine what’s been happening

today. And just to put it in context, this is on a scale that has never been seen in the country before, from north to south, from east

to the south to the Bekaa Valley, you have people trying to overcome this confession and model of politics, doing politics. And it surprised even

me.

But what I was trying to point out too is this impasse that identity-based politics has created in the region. As in, it works on the model of

dividing people and allocating the state resources according to confessions. You see the same being modelled in Iraq. The people are fed

up with that. Because ultimately, I think what’s happening is the return of the language of economic grievances. It’s the return of class politics.

And that’s what we are starting to see manifestations of. Not in a polished kind of ideological way like the old days, but in a much more kind

of visceral manner that in time I think will manifest itself through the secular political imagination into an organized movement for change.

That’s my hope.

AMANPOUR: Both of these countries, Vali, Iraq and Lebanon are heavily influenced by Iran, Lebanon through Hezbollah and Iraq, obviously, through

the massive Shiite majority that exists there. So, do you think that it’s even a starter to think, Vali, that there can be a move away from the

sectarian politics, again, where key positions are handed out and where it’s very, very much identity-based? I mean, we saw that that was a

massive problem in the emergence of al-Qaeda in Iraq, in the emergence of the whole sectarian divide, you know, up until about 2007 and then it came

back again.

NASR: Well, I think the problem runs much deeper. The problem is constitutional. You know, the constitution of Lebanon, going back several

decades, was built on sort of a confederacy of different sects and ethnic groups. So, each of them gets a piece of the government. Like the

president is always the modernite, the prime minister is always the Sunni, the head of the parliament is a Shiite. You cannot actually put a

government together without getting these different confederations of ethnicities actually agreeing on a government.

And the same is now happening in Iraq as well. So, I think the fundamental issue is there has to be constitutional change in these governments. Of

course, there are going to be winners and there’s going to be losers.

I think in the case of Lebanon, it’s going to be much more difficult because the confessional system is much older. And Hezbollah — you know,

the Shias in Lebanon are not a majority, they’re a plurality. And therefore, ultimately, you have to come up with the definition of Lebanese

citizenship that doesn’t include identity at all. So, that basically means a whole new constitution.

In Iraq, the Shiites are technically a majority of the population. It’s easier to sort of think of a constitutional arrangement that you would

treat Iraqis with one man one vote and you would not identify and base it on sects and they would not be voting for sectarian parties.

But in both countries, the difficulty is, can the protesters ultimately force an entirely new constitution on these countries? Because these

constitutions we have right now, by themselves, are faster and promotes sectarianism and then outside forces, whether it’s Saudi Arabia and Iran or

Turkey are going to take advantage of that because they can side with one sect as opposed to another.

AMANPOUR: I just want to follow up with this outside influence, because, obviously, it is considered that Iran was the biggest beneficiary of the

U.S. invasion into 2003. And as you pointed out, whether it’s repelling ISIS or domestic politics, Iran plays a huge role and the protesters are

angry. We just talked about how they have been storming the consulates.

You know, it’s been said that Trump, you know, in his maximum pressure on sanctions, has not changed Iran’s behavior in the region. But that these

demonstrations might, for instance, in Iraq and, indeed, in Lebanon, do you think that’s even possible, that Iran might get a little bit of a shock

from seeing people in these two countries take to the streets essentially against them?

NASR: I think the shock is there. I think Iran is shell shocked with what has happened. And I think Karl made a very important point, and namely

that, you know, the whole Iranian relationship with Hezbollah and with the Shiite militias and parties in Iraq is based on the idea of Shia brethren

sticking together in a sea of hostile Sunnis. That’s the way in which this relationship would work.

But as he was pointing out, you now have protesters in the street that don’t want to think in terms of a sectarian or regional sets of issues,

they want to think in terms of class and bread and butter sets of issues. And I think that does open the door for a different conception of politics.

I think that the problem is that if Iran can basically get a bloody nose in this, it can backtrack, it can make a concession. But if the

protests don’t produce a new constitution and viable governments, Iranian influence will be back.

AMANPOUR: OK.

NASR: So, it’s very critical. And that’s exactly — for these protests to get somewhere positive and that’s actually why it’s so shocking that the

U.S. is now taking advantage of this situation and is absent in this current environment.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, finally, in our final minute, Karl, what is it that maybe the West doesn’t get about Lebanon or, indeed, Iraq? I mean,

you know, we are saying the U.S. standing outside makes it even worse. Iran influence makes it even worse. What do you see as the big issue that

we don’t get right?

SHARRO: Well, I think, you know, historically, it has quite shifted because a lot of the road that we play see the smaller regional kind of

powers playing now and kind of like Iran trying to play a bigger role in Iraq or Lebanon than historically would have done have to do with the

collapse of the traditional arrangements between the superpowers, right?

And I think the U.S. has taken kind of a declining, diminishing role over the past 10, 15 years within the region. Some say, you know, for good

reasons. And that is, whether you like it or not, is creating kind of a power vacuum.

What I feel personally is any kind of calls for Western support of these protest at this particular performance (ph) will be misplaced. So, the

call to kind of make them understand the situation isn’t necessarily going to help because it will add kind of a suspicion to why outsiders are

intervening in our affairs. And what we are really fighting for is more national sovereignty and decision on our own.

AMANPOUR: It’s really fascinating. Karl Sharro, thank you very much indeed. Vali Nasr, thank you for joining us from Washington with your

expertise.

So, in the chaos and disruption, if it all can seem overwhelming. Our next guest offers a much needed spoonful of sugar to help the bitter medicine go

down in the most delightful way, that is to paraphrase the beloved Mary Poppins, played of course by the legendary actress, Julie Andrews.

She has a new memoire called “Home Work,” which covers the prime of her career from landing the role of Poppins to her massive success in the

equally iconic film “The Sound of Music.” These films continue to inspire millions of children. But behind the silver screen, Andrews says, was a

huge amount of hard home work. And I sat down with her this weekend here in London for a candid talk about her dazzling career but sometimes

difficult and dark personal times and not least how she manages to stay optimistic after a botched operation robbed her of that inimitable golden

singing voice.

Julie Andrews, welcome to the program.

ANDREWS: It’s a pleasure to be here.

AMANPOUR: And it’s a great pleasure to have you on board.

Look, all the work you have done is still so present in people’s experience. I mean, “Mary Poppins,” your first film, is as a theatrical

performance in London right now. It’s not the first time. How does it feel —

ANDREWS: Yes. I heard that it’s now back.

AMANPOUR: Yes. It’s back.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: How does it feel for you?

ANDREWS: Kind of wonderful. I mean, all a gift, all a bonus really. Life has been a bit like that in general.

AMANPOUR: Let’s talk just about “Mary Poppins” for a moment because that was your first ever film.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You came from vaudeville here in England.

ANDREWS: Yes, to Broadway.

AMANPOUR: And how? Who approached you to do “Mary Poppins”? Why?

ANDREWS: Well, I was on Broadway for quite a while in “My Fair Lady,” in, “Camelot,” and wonderful, wonderful musicals. And I was in “Camelot” with

Richard Burton, the wonderous Richard Burton. And Walt Disney came to see the show.

AMANPOUR: The man himself?

ANDREWS: The man himself. And apparently, I didn’t know it but he’d been advised to come and see that young lady in “Camelot.” And he came

backstage. And I thought he was coming back to just be polite and sort of say he enjoyed the show and so on. But he proceeded to the tell me about

this live action animation film that he was planning of P. L. Travers’ “Mary Poppins” and asked if I’d like to come to Hollywood and see the

designs and hear the songs and so on.

I was gob smacked. I said, oh, Mr. Disney, I would love to. But I’m so sorry, I’m pregnant. And he said, well, that’s all right. We’ll wait.

So, I had no idea that a movie takes as long as it does to — with pre- production and so on.

So, lo and behold, about nine months later with my baby in tow and my husband, we went off to Hollywood. And that first film was “Mary Poppins.”

AMANPOUR: It is amazing that he said he would wait. I mean, not many great directors, but it’s testimony, isn’t it?

ANDREWS: Well, I think it’s just that he — probably, the script hadn’t been completed and, you know, everything had to be prepared. But it was

such a wonderful thing to say. Oh, and then, he turned to my then-husband, Tony Walton, and said, what are you going to do, young man?

Tony said, well, I am a designer of sets and costumes, and he was relatively unknown in those days. And Disney said, then bring your

portfolio with you when you come, Miss Julie. And when he got there, he hired him on the spot to do all the sets and all the costumes in the movie.

AMANPOUR: And that’s a massive job because it’s all about sets and costumes.

ANDREWS: Well, imagine the two of us starting out if life, making movies and it was the greatest — I mean, Disney’s talent for spotting talent was

amazing. And he did that so many times with so many wonderful people, and Tony and me included.

AMANPOUR: You know, you play the nanny, obviously, in “Mary Poppins.”

ANDREWS: Obviously. Yes.

AMANPOUR: And then another nanny in “The Sound of Music.” And I read that you said that you were worried that you might by typecast as this English

nanny.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: I wonder whether you might agree with somebody who would say, in fact, you were one of the first female superheroes. Because “Mary Poppins”

is all about essentially a female superhero.

ANDREWS: Well, that’s true. Especially, these days —

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ANDREWS: with the #MeToo movement and so many things happening. I never thought about that. She was very forthright, wasn’t she, and forthcoming

and stated her mind and really —

AMANPOUR: And all the flying and the acrobatics and the —

ANDREWS: Yes, yes. She was — you know, I never thought of it that way, Christiane. Well, thank you.

AMANPOUR: And tell us, because it wasn’t the easiest of performances for you in terms of the harnesses and the wires and the physicality of it.

ANDREWS: That’s right. Well, there were so many special effects in the film, including the flying sequences. And, you know, in those days, they

didn’t have the amazing things that they have these days, which can make it so much easier to do animation as well as live action.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREWS: Oh, supercalifragilisticexpialidocious . Even though the sound of it is something quite atrocious. If you say it loud enough you’ll

always sound precocious. Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREWS: So, Disney really invented everything at the studio. And I was flying around in excruciatingly painful harnesses. But — and there was a

day when I very nearly got dropped. But — well, I did drop, actually, but it was just —

AMANPOUR: Were you like a sack of potatoes?

ANDREWS: Yes. But it was almost the last day of filming and they were saving all the important flying stuff, presumably at the end of the film in

case there was an accident, when I would have got most in the can already.

AMANPOUR: And sure enough, there was an accident.

ANDREWS: And there was, yes. I felt myself slipping a little bit on the wire. So, I called down and said, you know, when I come down, could you

please be kind enough to just bring me down gently? Because I think — well, wasn’t sure. At which point, I did go all the way to the stage. But

the good thing is, I had counterbalancing equipment as well, of course, I did. But I did come down pretty hard.

AMANPOUR: Again, very ahead of its time all of this. You got all the awards possible for “Mary Poppins,” Golden Globe, you got the Oscar.

ANDREWS: I know. It’s amazing.

AMANPOUR: It was pretty amazing. But there is this legend that perhaps you should have been chosen for the film version of “My Fair Lady.” You

were Eliza Doolittle on Broadway. And there’s a very funny story about when you accept the Golden Globe.

ANDREWS: That’s right.

AMANPOUR: Tell me.

ANDREWS: The producer, Jack Warner, who produced the film of “My Fair Lady,” was, of course, at the Golden Globe because it was also nominated.

And just before I went on stage, something made me say to the table where I was sitting, you know, I suppose somewhere along the way I should thank

Jack Warner because I had done “My Fair Lady,” I wouldn’t have been able to do “Mary Poppins.”

So, immediately all my chums said, oh, do it, Julie, just do it. And I thought, no, I can’t do that. You know, I’m so new in Hollywood. But when

I got up there some wicked impulse made me say, and of course, finally, I have to thank Mr. Warner to making this all possible in the first place.

And there was this awful silence. And I thought, oh, my God, I’ve — you know, my career has ended. But then they burst out laughing, including Mr.

Warner, who was a good sport about it.

AMANPOUR: And a very powerful mogul in Hollywood.

ANDREWS: A huge mogul but he was dear about it and he got was it was about.

AMANPOUR: And then you got — you did “Sound of Music.”

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Which, again, you know, is everybody’s favorite film.

ANDREWS: Well, how lucky could a girl get?

AMANPOUR: I mean, how many times has everybody seen it? I was fascinated though because that iconic shot of you emerging on the top of the mountain

and, you know, the camera pans up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANDREWS: The hills are alive with the sound of music, with songs they have sung for a thousand years.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: It was very hard work, wasn’t it, because you said it was done by a helicopter?

ANDREWS: Well, it’s no accident that I’ve called this new memoire “Home Work.”

AMANPOUR: “Home Work.”

ANDREWS: Because I had wanted to show that it’s not just red carpets and tiaras and glamour. It really isn’t. And as you well know, your business

and my business, it’s really a lot of work to get it right and try to do it well and long hours and much travel, and I just wanted to show that.

AMANPOUR: But in this particular opening sequence, the helicopter was used —

ANDREWS: Oh, the famous helicopter.

AMANPOUR: The famous helicopter was flying around trying to get shot.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And how did it affect you, physically?

ANDREWS: Well, it was just one very small piece of film but it was that moment of walking towards the camera and doing that spin at the beginning

of the film. And so, I started at one end of the field and the helicopter, with an incredibly good cameraman hanging out the side of it with this huge

camera strapped to him from the other end of the field, and we approached each other.

It really was the most extraordinary sight to see, this helicopter coming at me sideways, sort of crab like or grasshopper like or something across

the field as it got lower and lower and lower. And then I made my turn and then the director signaled for another take and another take and another

take.

But every time the helicopter went back to his side of the field and I went back to mine, the down draft from those jet engines just knocked me flat

into the grass. So, eventually, I was sort of coming up with mud and hay and a few things like that. I kept indicating to the cameraman, couldn’t

he please make a wider turn around me? And I just got that, fine, let’s do another take.

AMANPOUR: Let’s do it again.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And then, extraordinarily, and I didn’t know this until just researching the famous scene in the rowboat on the river in “Sound of

Music.”

ANDREWS: Right. Right.

AMANPOUR: Where you are making a surprise for Captain Von Trapp.

ANDREWS: Well, he’s suddenly come home and we didn’t realize that he was home.

AMANPOUR: Right.

ANDREWS: And so, I stand up in the boat and say, oh, Captain, are you home. At which point, we all tumble out of the boat. And just before that

take on the lake, the assistant director came wading out into the water towards me and I leaned down, I said, what? And he said, well, can I just

ask you something? The littlest one can’t swim. So, could you fall forward out of the boat and grab her as quickly as you can? And I thought,

oh, my God, a huge responsibility.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ANDREWS: And, of course, the boat rocked and rocked and rocked again and I went straight over the back with my feet rather like Mary Poppins and I’ve

never swum so fast in my life.

AMANPOUR: And for Little Gretl.

ANDREWS: Yes. And she was a trooper. I mean, she really was. She went under a couple of times. Poor child.

AMANPOUR: I mean, it is extraordinary. I mean, anybody would let that happen today, right?

ANDREWS: No. I don’t think so.

AMANPOUR: I mean, health and safety would be all over the place.

ANDREWS: Yes. I mean, of course, everybody was wading into the water to try and reach her. But they had asked me to try to get to her first.

AMANPOUR: So, “Home Work,” despite your public persona, which is incredibly sunny and incredibly optimistic and positive and almost sort of

jolly hockey sticks. British, right?

ANDREWS: Good old British.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You have, as you say, worked incredibly hard and you detail it if your memoir. But you’ve also experienced the dark side of life, the

moments of depression.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: The moments of —

ANDREWS: My husband was very depressive at times.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ANDREWS: And — which I knew nothing about and had to learn about and understand and recognize and there was just so much that was new and we

were building, raising a family, making a family, traveling a lot, making films together. It was a great deal going on.

AMANPOUR: You write in the book, “There was still that certain dangerous quality about him. I was aware that he abused pain medication at times,

although he seemed to be keeping it under control. He was given into making impulsive decisions and he was often excessive with spending. He

was impatient, quick to anger even. He was creatively brilliant with six ideas a day, it seemed, and totally charismatic. But he often —

ANDREWS: I got it right, as a matter of fact, I realize.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

ANDREWS: Yes. Go on.

AMANPOUR: “He often left me a little breathless,” is what you said. I just wonder how you managed your love, your husband —

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — your love of your work, your love of your children? How you managed it all at that time?

ANDREWS: Well, you do, and I think you’re so busy doing it that strangely enough it’s not until you’ve – you’re writing something like the memoir

that it really sinks in. So this – writing this book was kind of a mixture of emotions because when you’re coping with it at the moment, you don’t

think about as much how difficult it is or what’s going on.

AMANPOUR: And it affected you to an extent because you say during your Las Vegas shows you were making (ph), depression. Where does it come from? I

feel it lingering, lurking never far from the surface, and oh, it is black. I keep thinking that it’s chemical, menopausal perhaps, but it’s been

waiting around for years I think, a stalking shadow from my vaudeville days. I want to catch it, look at it, wipe it clean. It is to do with the

deepest me. I mean, it’s so revealing –

(CROSSTALK)

ANDREWS: Well, thank you.

AMANPOUR: — and so honest.

ANDREWS: I happened to keep diaries in those days and that’s what I wrote one day between shows in Las Vegas. And I just felt it very strongly that

day. It wasn’t any one particular thing. I think it was working in Vegas, being away from home, not feeling completely at ease with the work or being

away from home certainly. And it just – I felt very overwhelmed with another show to go at something close to midnight that I just put it down.

AMANPOUR: You know, you did this a long time ago. You put this down a long time ago.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And today, a lot of young people might feel incredibly comforted to know that somebody like you went through this –

(CROSSTALK)

ANDREWS: Well, I hope –

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: — and that you did a huge amount of therapy.

ANDREWS: Yes, I did. Well, I felt that I needed some answers, and that really does send you seeking answers where that kind of thing grabs you. I

didn’t have depression very often. My husband did, but I didn’t, and we were both in therapy anyway. But thank God for it because so many things

happened because of it. I think I was a better wife.

I think I might have been a better mum (ph) I hope because of understanding myself. And very kind therapist quickly realized that what I’d craved most

of all was an education, and I write in the book that he decided to give me one. And because I’d never really had one, never been to school really –

travelled with a tutor but never went to high school, graduated high school, never went to college, which I so wished I had done. So this very

bright sort of man, much like Merlin, gave me this wonderful education.

AMANPOUR: So that’s really interesting because you also say in the book – and there’s a quote here that you didn’t even tell your therapist for a

long, what, for a week or however long that you’d won the Oscar.

(LAUGHTER)

ANDREWS: I know.

AMANPOUR: You felt that somehow what?

ANDREWS: I didn’t want to be boastful and I didn’t want to show off and so many stupid things like that. I mean, of course today I would have blurted

it out, but I didn’t know him so well and I thought I’ll be discreet about it. It’s silly to burst into an office and say I won an Oscar.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Well, no. I mean, he must have known. It’s also broadcasted on T.V.

ANDREWS: I don’t know. Really I had no idea, but anyway, silly me –

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: It’s the proudest achievement for an actor.

ANDREWS: Well, most amazing that’s for sure. I think – this does sound Pollyanna-ish, but the doing is the best. And the rest is just icing on

the cake, and how lucky can one get if you’re lucky enough to be in that position, but truly everything’s collaborative. Everything’s – you learn

so much doing it, and it’s such a wonderfully interesting life. At least I thought so.

AMANPOUR: Well, I mean, it is, and to have given back so much is – must be incredibly satisfying.

ANDREWS: That’s the joy really.

AMANPOUR: But the doing of cause for you was also your voice.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And you write very poignantly it’s like opening your chest and bearing your soul. My singing teacher used to say to me singing with a

great orchestra is like being carried along in the most comfortable armchair. It can engulf you when you feel that incredible, intense joy

coming over you.

ANDREWS: Yes, it can. It can make you almost want to weep, and I think I further write that that’s the moment to give it to the audience because

that joy is so intense.

AMANPOUR: And so, you also say it was heartbreaking when you lost your voice and –

(CROSSTALK)

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — you couldn’t sing anymore.

ANDREWS: Well, actually that part of my life is not touched on in this –

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Not in this book, but you —

(CROSSTALK)

ANDREWS: — but I think everybody knows that I – that there was an operation and that I – sadly it wasn’t successful. And here’s the amazing

thing that I discovered so much else when I wasn’t singing anymore, writing and writing with my daughter and writing all our children’s books together.

And yes, I mourned the loss tremendously, but she said – my lovely Emma said, “well mummy (ph), you’ve just found a different way of using your

voice,” which I thought was – it was as if a weight dropped off my shoulders when she said that because I do as much as possible, include

music in everything I do and enjoy it still of course so much. I miss singing hugely, but I probably – thank God it happened at this age – a

later age in my life because I probably would have stopped fairly soon.

AMANPOUR: Amazing.

ANDREWS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You’ve had a second and third act.

ANDREWS: Well, yes. It is amazing, isn’t it?

AMANPOUR: It’s great. Thank you so much for being with us.

ANDREWS: Thank you, Christiane. It was lovely talking to you.

AMANPOUR: Lovely talking to you.

ANDREWS: Thanks.

(END VIDEO TAPE)

AMANPOUR: What a life. The incomparable Julie Andrews. So let’s now return to our main story, toxic politics and even street protests

and the role social media plays. Ev Williams is a digital pioneer who co- founded the platform Blogger in the late 90s. He went on to co-found Twitter and lead the company as CEO, but the billionaire entrepreneur has

since stepped down and his turned attention to Medium. That’s an online publishing platform designed to showcase longer and more nuanced content.

Williams told our Walter Isaacson that while Twitter needs to take responsibility for the quality of its content, it shouldn’t risk losing its

role as a place for the exchange of important ideas.

(BEGIN VIDEO TAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: So you do Blogger, which gets everybody easily onto the Internet with blogs. Then you do Twitter which

becomes a great, new form of social media. And you used to say it was to connect us. If you gave people a platform to connect us, it would make the

world a better place. Did that work out?

EV WILLIAMS, CO-FOUNDER, TWITTER: I don’t know if those are exactly my words, but there were certainly – that was part of the intention. I mean,

when I got excited about the Internet in the late 90s, to me the exciting thing was exchanging ideas and knowledge with anyone in the world, and that

still is the most exciting thing about the Internet to me. And so, I’ve basically spent my career building tools that help people share those

ideas. And yes, so it was Blogger, and then Twitter we made it much, much easier. And we did have a belief and an ethos that more people sharing

ideas and connecting means more better ideas succeed, we make better decisions, society is better.

I would say part of that is true. I think we’ve seen a lot of evidence of that. I would say it turned out to be much more complicated as well.

ISAACSON: Why?

WILLIAMS: We knew there were bad actors from the early days of the Internet. There was spam for instance and there was misinformation, but

the idea was the crowd would overwhelm the minority and the crowd would be generally good. And there was value to debating things in public. I think

the thing that was tricky is that a bad actor can overwhelm many, many good actors the way these systems are designed or have been designed. So that’s

–

(CROSSTALK)

ISAACSON: Wait, tell me the way they’ve been designed, do you think there’s something inherent in the algorithms that incent people to –

(CROSSTALK)

WILLIAMS: No, I think it’s actually – a ton of it is just human nature. I mean, we react to fear and threat and someone shouting fire in a theater

and that – so that person can ruin the experience for everybody else. That part is just physics and human nature. And so, that – when you replicate

that online and you give access to the whole world to ruin an experience with – for a group of people, turns out there’s enough bad actors in the

whole world to wreak a lot of havoc.

ISAACSON: The anonymity by having that so embedded in the system of Twitter, did that help incent people to say things they wouldn’t say face-

to-face?

WILLIAMS: I think the focus on anonymity is a little overblown actually. So if you look at – so Twitter is not by default anonymous. It’s by

default you put in your name. It’s just that you’re not forced to put in your name, and turns out there’s a lot of really good reasons for that

because one of the things we learned even back in Blogger days where there are places where freedom of speech is not a right and there are people who

have things to say and they want to connect to fellow citizens, and if they do that in they’re name, they will go to jail.

And so, Twitter was used early on by people in oppressive regimes to connect. And so that’s why it was always important to us not to do that.

And most people used Twitter under their name, and most bad actors, people who are out there saying the worst stuff, I don’t think the majority of

them, I don’t know the data on this, are saying it anonymously. They’re happy to be (bleep) under their own name. I don’t know if I can say

(bleep) on here, but they’re —

ISAACSON: You can say it on Twitter, can’t you? Or did get some —

WILLIAMS: Yes, but I don’t —

ISAACSON: No, but the one’s that really driving the hate conversations.

WILLIAMS: I think it’s the lack of consequences more than — so anonymity is related to a lack of consequences. The point is, even if you’re in

you’re — saying it under your own name, there are very little consequences to — to being hateful online and there are a lot of rewards, depending on

what community you’re a part of. So that — I don’t think that’s the root of the problem.

ISAACSON: What is the root?

WILLIAMS: I think the root of the problem — it’s not an online thing. It’s — it’s humans can have trouble getting along, and when you detach —

ISAACSON: Yes, but — but we get — we get along fine when we’re together in, you know, a dinner.

WILLIAMS: In — yes, in dinner when you say who can be at the dinner. I mean, if — if you invite just anyone to stop by a dinner and — and then

you will probably still have better behavior than online. I think the fundamental thing is when people are pixels on a screen, there is something

innate about us that causes us to — the way we’ve evolved isn’t that, right?

So, there are certain people who see the other people online as people and they feel an obligation to be — to treat them as people, and there seem to

be people who don’t have that. I think that’s part of the of the challenge of these systems in general, and if we — all of the benefits that come

with them come with that really big challenge.

ISAACSON: Is there someway we should be making people responsible for what they say on Twitter?

WILLIAMS: Yes, responsible. I don’t know what that means for sure, but I think there should be — you shouldn’t automatically have the ability to

interrupt other conversations, and this is part of the, actually, the protections that are being built into Twitter currently.

But, I think the whole idea of reputation is something that will — will come to the internet and I think that’s kind of important, because that’s

how society works, is you build a reputation and if you insult someone, you’re no longer invited to the party, that sort of thing.

ISAACSON: But, you’re talking about the reputation of the user. You’re talking about the user taking responsibility. Do you think that the

platform should have some responsibility for what goes on them?

WILLIAMS: Absolutely, the platform has responsibility. I think everyone at Twitter would agree that Twitter has some responsibility. I think when

it comes down to the nuts and bolts of what they should be doing and the service that Twitter provides to the world, which I do think is important

in being this open and free platform that where important ideas are exchanged and movements are created, you have to — it’s very unclear, to

me as least, and a lot of very smart people are thinking about this all the time, how to maintain that.

And as I say, and everyone should be nice and there should be no abuse and there should be no — like, I think people are messy and society is messy,

and we have to take some good with the bad and we have to keep trying to make it good. But even the extreme of what’s — we’ll just go on there and

police it, is — is just very naive and impractical.

And it’s not a matter of, will they spend enough money. It’s not doable, in the case of Twitter, to police Twitter to the degree that there’s no bad

behavior and then it gets very nuanced what is bad behavior. There are thousands of people and there’s thousands of counts that police the system

right now. I think not everyone understands that.

ISAACSON: You know, I ask my students at Tulane, if you could invent a new form of media, or social media, that wouldn’t have some of the problems of

the old one, they say the same things you do, which is, place where people take responsibility, place where there’s some curation. A place where,

maybe, you could build your reputation. And low and behold, that’s what you’re doing in inventing Medium. So, explain Medium to me.

WILLIAMS: So, Medium is a place where anyone can write and publish, and articles is the main form that people publish on Medium. So, anyone can go

on there. It’s — and just hit write and write something and thousands — tens of thousands of people do that everyday.

Most people just read, and so you can go on there and you can find articles and blog posts about every topic under the sun, I think, almost literally.

And, you can say what you’re interested in and you can start to get personalized.

And, you can really go and learn about really anything, from technical topics, to politics, to business, to science, and there’s both professional

journalists on there, who work full time on Medium. There’s independent writers, there’s organizations, there’s all types of people exchanging

ideas and knowledge.

ISAACSON: You base it, not on advertising, but on subscriptions, and you actually pay people for the content?

WILLIAMS: Right.

ISAACSON: This is like going back to the future. The — your old- fashioned concept, but it means you get high-value pieces.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

ISAACSON: Explain the theory.

WILLIAMS: Yes. So, the theory that — is that advertising, especially advertising online is the selling of attention. Almost all content on the

internet is paid for by advertising. And the way these systems have evolved is, the most attention for the least dollars is what advertisers

buy, for the most part.

And so, if you apply that — if you want to pay for the creation of something with advertising, the formula becomes, how little can I spend to

get the most attention.

ISAACSON: You make it click bait. You make it cats dancing on a piano.

WILLIAMS: You make it — yes, and you make it — it’s — it goes back to yelling fire in the theater.

ISAACSON: Right.

WILLIAMS: If you got paid for yelling fire in the theater, people would — and there were no consequences, you would do that. That, in many ways, is

what the internet has become and the algorithms and the advertising are all reinforcing this system, where whatever gets the most attention wins and as

cheaply as you can create that most attention, that’s what is rewarded.

ISAACSON: And I assume the flipside, that is a subscription model means you’ve got to produce something of value, or people won’t pay for it.

WILLIAMS: — value, yes. The subscription model is, if we produce something good, you pay for it. It has to be valuable enough to the person

receiving it to pay for it. If it’s not, they stop paying. That’s the whole basis, it’s a much more direct and it keeps us honest.

So everything on Medium, there’s no advertising. There — it’s kind of like the “New York Times” and other publishers where everything is for free

and you can read a certain amount, you keep reading more we ask you to pay.

ISAACSON: So, you just go to Medium.com and you say, hey, here’s what I want, and you start following things, almost as if it were Twitter, you

have things you follow, but on the other hand, this is curated deep content.

WILLIAMS: Yes, and you can follow anything from cooking, we — we have a partner publication with Mark Bittman, the former “New York Times”

columnist and he writes — he publishes and edits a publication called “Heated,” that’s about food.

So, you can say, I’m interested in cooking, I want to follow “Heated,” I want to follow this individual author, I want to follow this topic, and

then what you read makes it better overtime. And you can say I like this, I don’t like this, we’ll send you an e-mail, you get the app.

ISAACSON: You grew up on a farm in a tiny town in Nebraska, right?

WILLIAMS: That’s correct, yes.

ISAACSON: Did that help shape what you — your entrepreneurial spirit, your desire to connect, you’re desire to publish?

WILLIAMS: Yes. I think it relates to a lot of things. I’ve done — one is that I was very bored on the farm. I think boredom is a great thing for

kids. I think it leads to creativity. I think I worry about that today.

ISAACSON: Meaning you worry that we don’t bore our kids? We don’t allow them to bored.

WILLIAMS: I don’t think that kids are bored enough, yes. Because I was just so — I was very isolated and I was just in mind thinking what can

create, what can I do, what can I — and so, constantly trying to invent things, none of them were successful, but it was getting that habit.

ISAACSON: But you also liked magazines or something, right?

WILLIAMS: Yes, so I — as I got older, I just really wanted to be connected to the bigger world. I felt like — and I — and I found reading

was a fantastic way to do that, pre-internet reading meant magazines and books. And so, I read about this — everything. And I had this, felt like

an epiphany, where I read a book and it was about business or something. And I’m like, oh my gosh, I can learn what this person learned over years

of work in hours. That’s like a super power.

ISAACSON: Yes.

WILLIAMS: And that, I still feel that to this day, is something we take for granted, that there’s all this knowledge out there and you can get it

by picking up a book or reading an article. And so, I started doing that when I was a teenager, and I think that had a big part of getting excited

about the internet.

And finally, growing up on a farm, was sort of — entrepreneurship was sort of innate, meaning this idea that you have to be self-reliant, that you

aren’t going to go, necessarily — the model isn’t, oh, go find a job or go line up to an institution, there’s — it felt very natural to me from

day one to be on my own, scary, but it’s like, well what else would you do.

ISAACSON: And your first big company is Blogger. And in some ways you, at least, popularize and perhaps even create the word blogger, which is this

notion that anybody can publish anything and anybody in the world can see it.

WILLIAMS: Yes, we created Blogger 20 years ago last month, is when we launched Blogger in San Francisco.

ISAACSON: And people have to remember that before then it was pretty hard to blog.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

ISAACSON: I mean, you had to code your own pages.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

ISAACSON: And when you created Blogger, it’s just a box. It’s just type in here and hit publish.

WILLIAMS: Exactly. And — yes, weblogs as people called them then and then eventually blogs were just pretty nascent. There were a few —

handful of people doing them. And my friends at (inaudible) just said hey, we can make this easier.

We know how to write code. Maybe more people would want to do this. We called it Blogger. Blogger.com was available. Just register the domain.

And yes, it was just a big box and published them.

ISAACSON: And how did you get from there to Twitter?

WILLIAMS: Worked on Blogger for a few years, four years independently and then Google acquired it in 2003. Worked there for a couple years, which

was great, learned a lot. Left there, started a company with a friend called ODO (ph) which was a podcasting company in 2005 about ten years

before podcasts really took off.

That was going sideways. Had to — and within that company, had a brainstorm, a hack-a-thon as we called it. Some of the guys there came up

with Twitter. And we ran with that.

ISAACSON: You said that Trump is a sort of master for good for bad at being able to figure out how to use Twitter to further his own ends. I

mean, what do you think of that?

WILLIAMS: Well, I don’t like it personally. But I think it’s fascinating that in some ways Trump us like an early Twitter user because early

Twitter, one of the cool things, it felt like this connection to someone’s brain, like a more direct connection through the internet than we had

before.

Overtime, funny enough a lot of people on Twitter actually got more inhibited as the audience grew. It’s like oh, I’m not going to put just

anything out there doesn’t stop Trump. He just puts — apparently it’s still whatever’s in his brain just goes out in there. And it’s — and the

thing is that is compelling to people.

ISAACSON: But you tap right into the brain of somebody like a president is sometimes not a pretty sight.

(LAUGHTER)

WILLIAMS: Agreed. I mean it’s a mess. And there is power in it and it’s not–

ISAACSON: Does it give you any qualms that it sort of changed our political system both the way Trump has used it and then the way others

have used it?

WILLIAMS: Yes. I mean, I think there’s a ton of harm that comes from that, for sure. And it’s amplified and the media amplifies it and the vast

majority of people who see Trump’s tweets don’t see them on Twitter, they see them on CNN and Fox and everywhere else.

And I’m not blaming them more than Twitter, I just think it’s not great that we have these messages that spread ignorance and lies and hatred

amplified. Like first of all coming from the president of all people and then amplified by all media and Twitter and everything else say look at

this. It’s terrible.

ISAACSON: And you say that causes harm.

WILLIAMS: I think so.

ISAACSON: Then what do you do about it?

WILLIAMS: What do I do about it?

ISAACSON: Yes.

WILLIAMS: I don’t feel like I have a lot of power to do a lot about that.

ISAACSON: But if you could’ve changed Twitter, what would you have done about it?

WILLIAMS: I don’t know that we could’ve. I don’t know that we could’ve prevented Trump. I think the system — if you look at any — if you look

at Twitter or anything in retrospect and say well, let’s create a system that wouldn’t have led to those outcomes. Twitter probably wouldn’t be

Twitter today and something else would be Twitter today.

I think like the — had we created like a safe cultivated curetted place would it have grown? Would anyone have cared? Would there not been

something else to take it’s place? I think all those things would be true.

ISAACSON: But now you’re creating a safe cultivated curetted place, meaning Medium.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

ISAACSON: In some ways, are you doing that as a reaction to what happened at Twitter?

WILLIAMS: I’m doing that so people can deepen their understanding of the world and find good ideas. Not everyone wants to participate in the

frantic hectic advertising driven media world.

There is a hunger for nuance and complexity and that’s who goes to Medium. I’m creating the opportunity for reasonableness and depth to survive and

thrive. That’s why I’m doing Medium.

(END VIDEO TAPE)

AMANPOUR: EV Williams, CEO of Medium and Twitter co-founder. And Twitter has since announced its decision to stop all political advertising on the

platform with the current CEO tweeting we believe political message reach should be earned, not bought.

And that’s it for our program tonight. Remember, you can follow me, Walter and the show on Twitter. Thanks for watching “Amanpour and Company” and join us again tomorrow night.

(COMMERCIAL BREAK)

END