Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

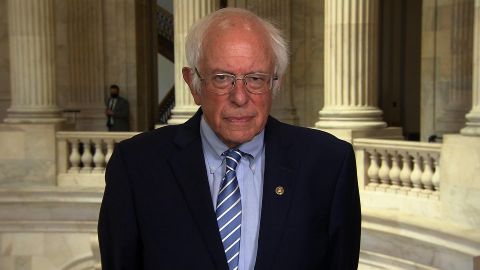

An exclusive interview with Senator Bernie Sanders. I asked him about Joe Biden’s swing toward more progressive policies and Democratic Party unity

heading into the election.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: They don’t like you here.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: When have other people’s opinions ever affected anything I’ve done?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The new film about Marie Curie, the brilliant scientist who discovered radioactivity and first woman to win a Nobel prize. I speak to

the director, Marjane Satrapi, of persepolis fame.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS, COLUMNIST, HARPER’S MAGAZINE: I have an inbox full of e-mails from young associate professors, editorial assistance,

people working at law firms who tell me that they are afraid to say what they actually think.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: The problem with cancel culture. Our Walter Isaacson speaks to one of the co-authors of an open letter saying free speech is under threat.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour working from home in London.

The U.S. election is just over 100 days away, and the race is becoming increasingly dominated, of course, by two issues, coronavirus and the

reckoning over racism.

And polls show Joe Biden leading President Trump, who now says the pandemic will probably get worse before it gets better. In response to these

multiple crises, the former vice president is calling for the largest public sector investment in generations, and he’s just unveiled a Build

Back Better plan, a $775 billion effort to help parents and caregivers, this right on the heels of his $2 trillion proposal for climate and

environmental justice.

In a new campaign video, Biden appears with the hugely popular former President Barack Obama, and the pair hold a socially distanced conversation

about the nation’s challenges.

But what is truly remarkable is the vital unity that’s being forged right now between Biden and his main rival for the nomination, Senator Bernie

Sanders, who says that Biden could be the most progressive president since FDR.

And the senator is joining me now for an exclusive interview from Capitol Hill.

Senator Sanders, welcome to the program. It’s good to have you here.

And am I right that this is an extraordinary shift, that this unity is something that we haven’t seen in a long time, certainly not the previous

cycle in 2016?

SEN. BERNIE SANDERS (I-VT): Well, I think there is an understanding of all Democrats, independents and a number of Republicans that Donald Trump is

the most dangerous president in the history of this country, that he is threatening the very foundations of American democracy, that he rejects

science, that he’s a pathological liar, that he’s a racist and a sexist.

And I think just that factor alone, among many other things, is bringing the American people together to say, this guy cannot be reelected.

AMANPOUR: But it is so interesting, because, you know, you and Vice President Biden fought on different, I guess, sides of the Democratic

spectrum.

You were much more progressive. He was much more centrist. And now this new plan and your new joint task force has really shown a shift to the

progressive causes that you have fought for.

Would you say it’s these — it’s not just President Trump, but it’s also the moment, the pandemic, the racial injustice, that’s causing this shift?

SANDERS: Yes. Yes, I agree.

AMANPOUR: How would you describe it?

SANDERS: Look, Christiane, I agree with that. I think it’s not only Trump, but it is the unprecedented moment that we are now living in.

I think everybody understands this. We’re looking at the worst public health crisis in 100 years. We’re looking at the worst economic meltdown

since the Great Depression. We are looking at millions of people demanding that we address the systemic racism that is so prevalent in American

society.

People want change. And I was very delighted that the vice president agreed to work with our campaign in putting together six separate task forces

dealing with the major issues of our country.

And I think we hammered out some agreements which will make, in my view, Joe Biden a very progressive president, if he, in fact, implements what has

been written.

AMANPOUR: So, I’m hearing if, if, if.

I guess, firstly, tell me what the main planks are in this joint task force. You say some measures, and if they’re implemented. What are the most

crucial measures that have been delineated, and what are you going to do to make sure they are implemented?

SANDERS: Well, what we’re going to do to make sure is that we’re going to continue building a strong grassroots movement in this country of millions

of people who increasingly understand that, at a time of massive income and wealth inequality, where billionaires are spending huge amounts of money

buying politicians all over this country, that we finally need a government that represents all of us, not just the wealthy few.

So, that’s what we’re going to do to make this happen. But I think what the task forces did in terms of economics is say that we have got to create

millions and millions of good-paying union jobs, rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure.

And that is our roads, our bridges, our wastewater plants, and our human infrastructure, which is child care and education and nursing home care.

And I think Joe has understood in this moment the need to go forward in that direction in terms of health care. He is not a supporter of Medicare

for All, as I am, but, on the other hand, he is greatly expanding public health to cover millions of people today who are uninsured or underinsured.

And he is prepared, as a result of these task forces, to take on the greed and collusion of the pharmaceutical industry, which now charges us by far

the highest prices in the world for prescription drugs.

In terms of climate change, I think he has come a very, very long way in understanding that we create a whole lot of jobs transforming our energy

system away from fossil fuel to energy efficiency and sustainable energy.

In terms of education, in terms of criminal justice, he has also made very significant movements in a progressive direction.

AMANPOUR: So, Senator, I think I quoted you as saying it, that Biden could be the most progressive president since FDR.

If you did say that, it’s pretty dramatic. I mean, you’re really going far, far out on a limb there. That means you must support what he’s doing. And,

therefore, do you believe that your supporters will vote for him?

Because remember what happened in 2016, when about a quarter did not vote for Hillary Clinton.

SANDERS: No, that is not true. Christiane, that is not true.

AMANPOUR: OK.

SANDERS: It was not a quarter of our voters who did not vote for Hillary Clinton. That is a false number.

But, more importantly, the reason I say that I think that Biden has a chance to be the most progressive president since FDR is, that is exactly

what Joe Biden said to me. And I think he has said that publicly.

He understands the severity of this moment. We have tens of millions of people who have lost their jobs, lost their health care, people who are

hungry today. We have an educational system which is lacking for low-income and working class kids. Climate change is out there.

Joe understands this is an existential problem for the planet. So, in talking to the vice president, and his own public proclamations, I think

he’s making it clear that we need to, in a very bold way, start addressing the crisis working-class families today.

Half of our people are living paycheck to paycheck. That was before the pandemic. Over half-a-million people in America are homeless; 87 million

people are uninsured or underinsured. It is a major economic crisis, and I think that Joe understands that and will do his best to address it.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, if my figure was wrong, though, it’s nonetheless a significant Bernie-or-bust number.

But my question to you is this, that there are still — according to the polls, despite the lead that Biden holds right now, there are still young

people who are less than excited and progressives in the minority communities.

What can you do, and are you confident now that they will do what you’re saying, come to vote because of the gravity of this moment?

SANDERS: Let me go back a moment on your numbers.

My understanding is, more people voted who voted for Hillary Clinton in 2008 voted for John McCain than people who voted for me in 2016 voted for

Trump.

But to answer your question, I think what the Biden campaign does understand is that we did really, really well among young people, white and

black and Latino, Native American, Asian American. We did pretty badly among older people.

And what I think the Biden campaign understands, they’re going to have to reach out and bring those people into the fold. And I think they are making

some success.

We had the Sunrise Movement, for example. We had the leader of the Sunrise Movement sitting, along with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others, as part

of the climate change task force. And she is out there saying that Biden has moved in a significant way to address the crisis of climate change and

to move this country away from fossil fuels.

So, I think Joe understands that. He understands the need to speak to young people, to people of color, and I think the campaign is doing its best to

do that.

AMANPOUR: So, let me expand a little bit. You mentioned at the beginning Republicans. Some Republicans are also looking askance at this current

president.

And I just want to ask you to react to what the former Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan said, is quoted by “The New York Times.” He just

said recently that Biden is winning over Trump with suburban voters 70 to 30 and — quote — “If that sticks, he cannot win states like Wisconsin,

Michigan, and Pennsylvania.”

Do you agree with that analysis?

SANDERS: Yes. I think that Ryan is right.

And what is happening is, you have a lot of Republicans — quote, unquote – – “moderate Republicans” who may not agree with Democrats on our economic message, may not agree that we have to raise taxes on the wealthiest people

in this country, may not agree in every instance with the program that Democrats are bringing forth.

But they also understand that they don’t want their kids to grow up in a country where we have a president who is a pathological liar, where you

have a president who is a sexist, who is a racist, who is a homophobe and a xenophobe and a religious bigot.

So, you have a lot of people who will disagree on a lot of issues, but who do believe that we have to have a president, when you turn on the

television and you see him, you’re not embarrassed. You don’t say to the kids, go to another room. It’s somebody that at least you can say, all

right, he is reflecting American values to the rest of the world.

That is certainly not the case with Donald Trump. And I think a lot of suburbanites understand that.

AMANPOUR: So, when it comes to values, obviously, what’s happening right now in your country is this big uprising, incorporating not just the black

community, but many, obviously, of the population.

And racism has become a big issue in the election. So, I want to ask you — combating it, anyway. I want to ask you just to reflect a little bit on how

these great civil rights leaders who we have just lost. John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, Joseph Lowery, all have just recently or this year died.

Just first, what impact did those men have on your political thinking and this moment right now?

SANDERS: Well, as a young man, Christiane, long, long time ago, I was involved in the civil rights movement.

When I was a student at the University of Chicago, I got arrested protesting segregated schools, led the effort — helped lead the effort

against segregated housing. I was in Washington to hear Dr. King in his famous “We Have a Dream” speech.

So, obviously, King and all of these leaders, including John Lewis, who’s a friend of mine for many years, have impacted my life.

And the struggle that we are engaged in right now, it seems to me, is manifold, and that, number one, we need to make sure that all our people in

the wealthiest country in the history of the world have a decent standard of living, and that we understand that, when we talk about systemic racism,

that is also economic racism.

We’re seeing that right now in the pandemic, where it is the African- American community, the Latino community, Native American community that is suffering the most because of preexisting conditions, among other things.

They have the jobs that are putting them in contact with the virus. They do not have the adequate health care.

So, what we have got to do now is end bigotry in this country. Systemic racism is unacceptable, not acceptable that black women are dying at three

times the rate of white women when they give birth to babies, that infant mortality in the black community much higher than in the white community,

that white families have 10 times the wealth in black families.

And on and on it goes. So, we have got to combat systemic racism. We have to combat income and wealth inequality. We have got to combat the housing

crisis. We are the only major country on Earth not to guarantee health care to all people as a right.

Our current health care system is a total disgrace, designed to make huge profits for the insurance companies and the drug companies. Got to deal

with that. Got to deal with climate change.

So, again, all these things are out there. I think the American people, Democrats, Republicans, independents, understand that Donald Trump is

completely incapable of addressing these crises.

AMANPOUR: Well, right now — and it may or may not be an election ploy — I don’t know — but he’s being the law and order president.

And, as you have seen, obviously, because it’s happening over where you are, in the city of Portland, there are federal troops that are taking

people off the street and taking them who knows where, unmarked, unknown destination.

And now the president is apparently going to order them to Chicago and maybe to a city in New Mexico.

And I spoke to Representative James Clyburn. And this is what he told me about his fear for what’s going on.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

REP. JAMES CLYBURN (D-SC): We have got a president who is refusing to say he will peacefully give up the office if he loses the election. That’s the

way you set up these kind of totalitarian governments.

We cannot allow this government to become a banana republic, and that’s what this guy is trying to do.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, he was talking to me about the other question I asked him, which are the fears for the election security.

Can you address that? And having run for office, you obviously are very concerned about it, and the Russian interference. And now we know that Joe

Biden has put the Russians on notice that he will not tolerate it, unlike what candidate Trump or President Trump has done.

SANDERS: Well, you have asked a lot of questions.

Let me just start off with what’s happening in Portland and what Trump wants to see in other cities. It is absolutely outrageous. Representative

Clyburn is exactly right.

We cannot — we are a democratic society. We’re a nation of law. And you don’t send federal troops into cities all over America, superseding the

desires of mayors and governors and local police chiefs. That is outrageous.

And I kind of think that what Trump is doing is trying to become provocative, sending in federal troops, bringing forth more demonstrators

against them, and then continuing the spiral of violence.

So, I think this is a very dangerous idea. We are working right now on legislation that will prevent federal troops from doing what they are doing

right now.

So, that is a major concern that I think every American, whether you’re conservative or progressive, should be concerned about. We cannot have a

movement in this country toward authoritarianism, where a president says, I will send troops anyplace I want, I don’t care what local officials want.

That is what a totalitarian society and a police state is all about.

AMANPOUR: And I just want to ask you a final question, because amongst many in the post-George Floyd moment, there is a cry for defund the police.

Now, James Clyburn doesn’t agree with that. He’s very worried that it goes back to the ’60s, the burn, baby, burn, and puts the movement on the back

foot. Joe Biden, I don’t think, agrees with that.

Where do you stand on that? And how can you persuade voters that Democrats do stand for proper law and order, but they don’t stand for the

militarization of the police that we have seen?

SANDERS: No, that’s exactly right.

Look, if we mean by defunding the police, and understanding that there is a lot of stuff that police departments now are forced to do — they’re

dealing with homelessness. Are they the best trained people in the country to deal with homelessness? No, they’re not. They’re dealing with drug

addiction and alcoholism.

And I think that we can move forward to redefine what the function of a police department is. And that’s the direction I think we need to go.

We also need to make police departments of this country look like the communities that they are representing. And we need to get this heavy-duty

military equipment out of local communities, because, otherwise, the police look like an occupying army.

So, there is a lot, a lot, a lot that has to be done in terms of police reform. But I think the vast majority of the American people do not believe

it is a good idea to simply defund the police department, have no police departments at all.

There is no city in the world that exists under those conditions.

AMANPOUR: Senator Bernie Sanders, thank you so much for joining me tonight.

SANDERS: My pleasure. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Now, another fighter for racial justice died today. He is Andrew Mlangeni who was 95 when he passed away in his native South Africa after a

lifetime of struggle against the white’s segregationist apartheid regime. And he was the last surviving codefendant convicted alongside Nelson

Mandela in 1964. That Rivonia trial began in 1963 where he and Mandela were accused of trying to overthrow the state.

Mandela told the judge and therefore the world that he was ready, “if needs be,” to sacrifice his life for the cause of freedom. Mr. Mlangeni urged the

judge to, “remember what we, African and nonwhite people, have had to suffer. That is all I have to say except to add, what I did was not for

myself but for my people.” Both were then marched off to prison for more than 25 years, but their sacrifice and their struggle brought freedom and

racial reckoning to South Africa in the end.

Meantime, as the world confronts one of its worst public health disasters in generations, in many quarters, science is under attack, as we’ve been

discussing. And now, a new film reminds us of the importance of scientific innovation and knowledge. “Radioactive” captures the life of Marie Curie,

the first women to win a Nobel prize along with her husband Pierre for discovering polonium and radium. Here’s a clip from the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ROSAMUND PIKE, ACTOR, “RADIOACTIVE: I want to tell you about radium, a most peculiar and remarkable element because it does not behave as it

should.

Science is changing, and the very people who are running science that people who believe that the world is flat. And I’m going to prove them

wrong.

SAM RILEY, ACTOR, “RADIOACTIVE”: You’re Marie Sk?odowska. I’m Pierre Curie. Your science is brilliant.

PIKE: You’re proposing a partnership.

RILEY: That’s exactly what I’m doing.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And she won a Nobel in her own right for chemistry. But Marie Curie faced incredible obstacles as a female scientist. Joining me is the

film’s director, Marjane Satrapi. She shot to fame when her graphic memoir, “Persepolis,” about life in revolutionary Iran hit and in 2007, the film

version won her an Oscar nomination.

Marjane Satrapi, welcome from Paris.

I guess the first obvious question to you is, could you ever have imagined — maybe you did — that this film would hit right in the moment when

science is front and center of our public debate right now.

MARJANE SATRAPI, DIRECTOR, “RADIOACTIVE”: No, not at all. And it is unfortunate that today in 2020, people, they don’t still — they still

don’t trust science. I mean, if it is something that is factual, this is not subject of interpretation, it’s science. So, that is the only factual

thing that we possess. So, we better trust it.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you, then, Marie Curie. What made you curious about doing a biopic on her? It wasn’t the first one, obviously. What were

you looking for that was not told in the other depictions of her life?

SATRAPI: Yes. Basically, I was brought up, you know, by the idea that Marie Curie should be a role model for me because my parents wanted me to

be an independent woman. So, she was like the role model I had to follow. So, I knew lots of things about her. But then when it came, you know, to

make a film about Marie Curie, as you say, it has been filmed since 1943 about her and the story is really good to be said again if that is a new

point of view.

So, the good thing with the script of Jack Thorne was that not only was it about the life of Madame Curie, but it was also about her science, and

while we’re talking about the science, it was also the aftermath of the science and the effect that science has — had in the worked for the best

like the cure of cancer, and the worst would be the atom bomb and Chernobyl. So, we actually talk about all the subjects and it kind of made

it like a complete story. So, it was very exciting to make this film that went beyond the biopic.

AMANPOUR: So, I want to ask you, because some reviewers have taken — you know, they have objected to some of the flash forwards. But I think I read

you saying that you would have never done the film if you couldn’t have that forward looking, sort of the results of her work. Explain to me the

way you use flash forwards.

SATRAPI: Well, the fact is that Marie Curie made a discovery in the beginning of the 20th century. I mean, the word radioactivity has been

created by her, that actually changed completely the face of the 20th century, because at the time that it was discovered from the Ancient Greece

up to the beginning of the 20th century, everybody knew about cancer but did not know how to cure it. So, it was a huge advancement in medicine.

But we can — you cannot talk about that without talking about the side effect of that, because whatever we have in the world, whatever — which is

invented, which is discovered in the world, we always can use it in the different words and — in the different ways, sorry. And the problem is not

the scientist, the scientist just discovers it. It talks about us, the ethic of we human beings, what do we do with these new discoveries, with

this invention? How do we deal with all of that? So, it was impossible to talk about her and this discovery and not talk about the rest.

And to be frank with you, I don’t like very much the biopic. It’s always, you know, extremely heroic, and the person I have in front of me doesn’t

look like a human being to me. So, I just wanted to be — to make a Marie Curie that was a real human being with all what is a human being, that

means his or her own imperfection.

AMANPOUR: Well, you know what, you succeeded in that, because she doesn’t come across as very nice. I mean, brilliant, obviously. She loves her

husband, she is brilliant at science and she’s phenomenal, but she’s also quite brusk in her manner. And I just want to play a little clip from the

film where she’s seeing her husband again as he comes back to being the only one to accept their first Nobel, which they both won, but he went

there and accepted it in Stockholm. Let’s just play this clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PIKE: You stole my brilliance and you made it your own. You never should have gone without me.

RILEY: You had just given birth. You were too ill to travel and you didn’t even want to go. What was I supposed to do? This is bigger than both of us,

Marie, and someone had to be there to represent the achievement.

PIKE: You never did understand. You were angry because they didn’t want you as one of their own.

RILEY: Oh, you fathom me so well.

PIKE: I was angry because they were wrong. But I never wanted any of this, I just wanted to do good science.

RILEY: And did I not make you a better scientist? Are we not better scientists together?

PIKE: Of course we are, because you have one of the finest minds I’ve ever met, it just so happens that my mind is finer.

RILEY: Your main problem, Marie, is your arrogance.

PIKE: My problem is you and the fact that I love you so ardently.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Honestly, Marjane, in that clip you say everything about her, her professional arrogance, her belief in herself, her love for her

husband, her admission that together they were, you know, a great team. It really is. It’s quite a scene, that. What’s the truth behind how they

worked? I mean, obviously, presumably, that is the truth. But who was the dominant scientist, if it’s possible to be able to say?

SATRAPI: Well, the thing is that, you know, when you talk about, she was difficult, I think this is a trait of character to be forgive very easily

if it comes through as a man. I mean, a genius man. By definition, he has a right to be difficult because he’s such a genius. So, he does not have the

time to take care of the fact that if people like him or not because he is concentrated and focused on his work.

As soon as it comes to women, I don’t know, for some reason we always have to be mild and sweet and convenient, and I think she was such a genius and

so focused on her work that she did not have the time to ask herself if the way she was or the way she behaved was pleasant or not because she had

something else to do.

Now, the relationship that they had together, for me, is quite unreal, because it’s a couple at the end of the 19th century. And I find her

extremely modern, because she actually does what she’s supposed to do. She does not really make a case of her womanhood.

She really makes a case of the science. But I think even more modern than her is Pierre Curie, because he wants a woman equal to him. He wants a

colleague. He wants another scientist that he can share his science with.

And I don’t even think that, in 2020, you have so many of these kinds of men running in the street. So he was really extremely modern. I think they

had a huge passion.

And from what I know about her, I would not call her arrogant. I think she’s very conscious about the talent and the intelligence that she has,

and she should because she’s like one of the most intelligent people that has ever existed in this world, together with Einstein and Planck and other

things.

But I think it’s a passion. And I saw photos of her like before and after Pierre Curie’s accident. After Pierre Curie’s’ accident, there was only on

one single photo where she smiles. And she really becomes somebody else.

I think it was a — she was passionate in all the aspects of her life, from her love life to her science life. Everything she did, she made it with

great conviction and great passion.

AMANPOUR: Exactly.

And you refer to the accident when he was knocked down by a horse and carriage, and he was killed, and her life sort of — her personal life was

never, as you say, happy really after that.

Professionally, she went on to do great things.

SATRAPI: Of course.

AMANPOUR: But can I just perhaps sort of do a little bit of throwback to your own life?

You became a massive figure with your incredible book “Persepolis” and then obviously the film, as a young — well, you were born, you grew up in Iran.

And it was at the time of the revolution. Your parents were anti-shah, but then they were upset at the Islamic revolution that took place, rather than

a democratic secular revolution.

And also have that sort of immigrant or migrant connection with Marie Curie. She came from Poland. You came to France from Iran.

But I just want to play this little clip where you, from the 2007 “Persepolis” film, where your character is playing Che Guevara.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Stevie Wonder.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Julio Iglesias.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Pink Floyd.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Jichael Mackson.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): Lipstick, nail polish, playing cards.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR: Iron Maiden.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): How much?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): A hundred.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): Sixty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): Sixty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): Sixty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTOR (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): What the hell is this outfit? Punk shoes.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Fifty.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): What punk shoes?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Those.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): They’re sneakers.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): It’s punk.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): I play basketball at school.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): And this jacket.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): And that? Michael Jackson.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): A symbol of decadence.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Not at all, madam. It’s — it’s Malcolm X.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Are you kidding me?

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Michael Jackson.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Lower your scarf, you little…

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Follow us to the committee.

UNIDENTIFIED ACTRESS (through translator): Sorry, madam. My mother is dead. My evil mother-in-law is taking care of me. She will kill if I don’t

go back home. She will burn me with the iron. She’ll force my father to put me in an orphanage.

Have mercy. Please, madam. Mercy. Mercy. Have mercy, madam.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, you manage to see off the ideological police there.

But what is your experience as a migrant in Europe right now? And I ask you, I guess, because you’re right in the middle, like we all are, of this

uprising for racial justice, and France, which likes to consider itself sort of universalist and no ethnicities allowed, everybody is French.

Clearly, that’s not the full story. What is happening there, and how is the reckoning going on the streets there?

SATRAPI: Well, the thing is that it’s quite unfortunate that, in 2020, people, they still talk about races, because we know scientifically now

that the human race is — different races does not exist.

We have different ethnicity. But then you have like human race, and then you have the cat race and the dog race, so different human races is not an

actual truth.

It’s just we just have different colors, different shapes. But this is our ethnicity. It’s extremely unfortunate, but it’s good also, at the end, you

know, we talk about this thing, and it had to open at one point.

And, yes, I had this experience that I came because, like, I could not do what I wanted to do in Iran, so I had to come to France to have the freedom

to be able to do that.

That is always a judgment of the other one that they think, when you come, you’re there because you want to take their bread and their work and have a

great time, which is not true.

Most of us, we go because we don’t have any other choice. Now I’m talking really about the immigration. It’s — for most of the people, it’s a

question of death or life. They’re leaving wars. They’re being persecuted. They have problems.

People — nobody leaves their own country because they think it’s fun. Everybody loves the place they’re born, they love the food they eat, they

love the geography of the place that they are — if we go, it’s because we don’t have any choice.

And the moment that people, they have this empathy and the compassion to understand that and see in front of them not an abstract notion of the

migrant, but a human being who is in need of freedom and in need just to survive, then probably they have made a step forward.

But I think 2020 is kind of really late to start thinking about this thing. This should have been a long time ago.

AMANPOUR: Yes, but it does seem to be a moment, doesn’t it, that is now at least happening in so many of our countries.

I guess, just very finally, back to Marie Curie. You spoke to her grandmother in your research.

SATRAPI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And she said, on no account, make her out into a feminist suffragette icon. I found that really interesting.

SATRAPI: Absolutely.

Yes, she told me they would recuperate her and they would make her an icon of feminism. And she was not.

And the sentence that is said in the film, when she say that she suffered much more from the lack of funds than the fact of being a woman, it’s her

granddaughter who told me that, because this is a letter that Marie wrote to her daughter Irene, so the mother of this granddaughter, obviously.

And she said, please put that in the film. And that is what I did.

I think Marie Curie, it’s not that she is not — she would support women, et cetera, but she was not like a figure of feminism.

AMANPOUR: OK.

SATRAPI: But, at the same time, she is the real feminist, because she’s a factual feminist. By what she does, she proved that not only she is equal

to men, but, most of the times, she is even far superior to them.

AMANPOUR: And maybe even, as you said, Pierre was as well a feminist before his time.

Marjane Satrapi, thank you so much, indeed, for joining me.

SATRAPI: Oh, absolutely. Pierre was super feminist.

Thank you, Christiane. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: It comes across. Thank you.

Now, an online playbook seems to be emerging around some of the important, but difficult political conversations these days. Someone says something

deemed offensive or troubling to someone else, and social media goes into a frenzy and that person is effectively canceled.

Well, an open letter recently published in “Harper’s” magazine claims that this poses a threat to free speech. It was signed by 153 prominent writers,

academics and artists, including the likes of Gloria Steinem and Salman Rushdie.

It’s become quite controversial.

Here is our Walter Isaacson speaking with the co-author of that letter, Thomas Chatterton Williams, who’s a contributing writer for “The New York

Times” magazine and a columnist at “Harper’s.”

And they discuss our current age of moral reckoning.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane.

And welcome to the show, Thomas Chatterton Williams.

THOMAS CHATTERTON WILLIAMS, COLUMNIST: Thanks for having me.

ISAACSON: Explain to me this incredibly famous now letter. What was the point of it? What caused you to write it?

WILLIAMS: The letter comes out of a conversation that I have been having with four of the other writers who drafted the original text with me about

a kind of atmosphere of censoriousness and impermissiveness that has been affecting all of our culture and media institutions for some time now.

It doesn’t come out of one event in particular, but a kind of mood has set in, a mood that feels as though we are less and less free to speak in ways

that deviate from increasingly rigid orthodoxies. We are less and less free to experiment and perhaps even sometimes make a mistake in a landscape

rapidly evolving norms.

ISAACSON: Can you summarize for us exactly what the thesis was and what arguments you were making?

WILLIAMS: Yes.

Well, we were saying that you cannot have a just environment without that environment being free. So freedom and justice are inextricably linked. We

stand with the protests against police brutality, and we stand with the larger movement that has been starting a conversation about making our

workplaces more inclusive.

We’re for maximum inclusiveness and tolerance and the freedom for people to have diverging views on good faith. We see — we uphold those values as

fundamentally liberal values.

And we see a creeping extremism on the left and the right that makes the kind of atmospheric censoriousness, and that is in opposition to these

liberal values.

ISAACSON: What has surprised you about the amazing reaction to that letter?

WILLIAMS: I mean, I have been surprised by the sustained interest in this topic, and I have been heartened by it.

We’re approaching two weeks of constant conversation. Yesterday, 100 Spanish-speaking intellectuals, including the Nobel laureate Mario Vargas

Llosa, signed their own open letter in support of our manifesto and saying that this was an issue that transcended national boundaries.

I think we really hit on something that resonates with people that is not made up or just the kind of fear elite losing some positions at “The New

York Times.” I think we really hit on something that is real.

ISAACSON: Sometimes, it seems to me that these discussions are true, and the points you make are true, but that they can be overblown a bit.

We see a few really bad examples of censorious culture. But then we see recycled the same handful of incidents. How bad do you really think this

problem is?

WILLIAMS: Well, here’s the thing. You have a few incidents that people tend to talk about over and over again. And then you have some cases that

never make it into the public consciousness.

But it just takes a few cases, actually, to have an enormous effect. So, the way that — the kind of perniciousness of cancel culture is that it

thrives on public humiliation and shaming. And so all you have to do is take somebody and make a significant enough example out of them, that you

have an enormous effect on all of the onlookers.

And so that’s what we’re really talking about. We’re not just talking about high-profile cases. And we’re not just saying that the people signing this

letter, many of whom are very successful — and, frankly, that success can’t be taken away from them at this point. But they’re saying that this

larger culture matters because of all the people you don’t care about who then like make themselves smaller in order to not be publicly humiliated.

And there are some cases that I can talk about that are pretty chilling, in and of themselves, regardless of the onlooker effect.

ISAACSON: Well, give us some of those cases.

WILLIAMS: Absolutely.

Just recently, Gary Garrels, a curator at a museum in San Francisco, was forced to resign for saying simply that he would continue, even — in his

efforts to diversify the museum’s art collection, he would continue to also buy white artists.

This sparked a revolt and he was forced to resign and was deemed a white supremacist.

You have the case of David Shor, which now has become quite well known, the young data analyst at Civis Analytics, who somebody retweeted research by

Omar Wasow, a black academic at Princeton University. And I hate to even put his credentials in racial terms, but you kind of have to point out that

he’s a black academic.

And David Shor retweeted research of his showing that, in election years, when there’s nonviolent and violent protests, the violent protests can have

an adverse effect on democratic politics — on the election of Democratic candidates.

And he used Richard Nixon as a case study. David Shor retweeted this research without adding commentary and was quickly kicked out of a

listserv, a progressive listserv (INAUDIBLE) and then fired.

ISAACSON: Well, I’m old enough to remember the late ’60s, the ’70s, the ’80s, when — people talking about political correctness, and then writing

about the thought police.

And every decade, we have some pushback on this. Has it actually really gotten any worse?

WILLIAMS: You know what I think is really different, and we’re only starting to understand how important this change has been, is the

technological shift that’s happened in the social media era.

So I really do believe that enough of a quantitative change becomes a qualitative difference. So people have always been held accountable or

fired or even blackballed and ostracized.

What is new now is that we have these rapidly shifting norms. Somebody trips over a new norm that isn’t even yet spelled out in stone, that is not

part of the employment contract or what have you, is not even necessarily a fully accepted social norm.

They’re called out online. And there becomes a mass kind of reaction to this, with many strangers involved and some high-profile voices, and it

whips up a fervor that targets not just this person, but this person’s employer.

And then that gets into the person’s H.R. department, and very swift kind of reactions are made where the person is canceled, effectively, so that

the institution or employer can be done with it.

But even worse than that, a kind of stigma attaches to the person that has been targeted, and they become outside of the sphere of employability

elsewhere, or they retract their novel, or they resign from a board, and they don’t go on another board.

And these might seem like, well, those are nice problems to have. But this trickles down. I have an inbox full of e-mails from young associate

professors, editorial assistants, people working in law firms who tell me that they are afraid to say what they actually think.

They have never fully said what they think because they’re so afraid of the repercussions that could come their way.

ISAACSON: But aren’t there a lot of types of views and comments that deserve to be stigmatized? Isn’t that how we set the bounds of civil

discourse?

WILLIAMS: Absolutely.

And I think that when you talk about someone like the lead writer on Tucker Carlson’s widely viewed show on FOX who lost their job recently when it was

discovered that they were operating under an alter ego that was saying pretty awful, racist stuff, I’m sure that that violates some aspect of

their employment contract. That’s a known line that was crossed.

The problem with cancel culture is that you’re often getting caught up in things that haven’t yet been cemented in the public square as black-and-

white violations. They’re evolving norms. And part of your punishment is to make the norm stick.

And so that’s kind of scary. And you don’t really have a way of defending yourself when you don’t know that you’re even violating something.

ISAACSON: What about J.K. Rowling? She’s a signer of the latter. She has controversial opinions on transgender rights. Did that distract from this?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that if she has views that are controversial and are worthy of being refuted, then the best way to do this is not to say

that they’re forbidden and cannot be aired, that they have to be hidden from adults who can be convinced and prevailed — their reason can be

prevailed upon.

But those arguments should be brought out and should be refuted openly. And I think that she’s — I don’t know her, but I think that she would welcome

that kind of debate as well. She’s somebody who has a long track record of standing for liberal values.

And so I thought that the strength of the letter was that a wide variety of people can sign it, and that those values will be worthy, independent of

the signatories.

And I want to say that I come from a kind of viewpoint that Bayard Rustin articulated so well, which was that, if a bigot says the sun is shining, I

will still say the sun is shining because my loyalty is to the truth.

Now, I’m not saying that anybody on the list was a bigot. We wouldn’t have invited anybody to sign if we believed that they were bigots, but I also

want to detach — I want to refute this notion that the truth is dependent upon who is at any given time articulating it.

ISAACSON: You say you wouldn’t allow anybody to sign if they were bigots, and that maybe, when we have platforms, we should draw the line at bigots.

How do you draw that line, though?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think that, in our employment — in our terms of employment, we have regulations that work for what is bigoted. And there

are things that you cannot say and do at work that are very clear, and people get fired.

I think a lot of us, we can parse these things, but a lot of us understand what certifiable bigotry is. On the edges, where we’re redefining and

perhaps in a way that is very necessary, we’re redefining what exactly we believe and want to believe bigotry is, then I think we have to have —

again, we have to have more generosity in allowing people to be convinced and arguments to be made and people to be persuaded before we get to the

gotcha phase and the public humiliation and punishment phase.

ISAACSON: We have seen a lot of incidents recently in which there’s both issues of race and then the very censorious or huge Twitter backlash

culture.

One of them was about the birdwatcher, the African-American men birdwatching in Central Park, and the white woman who then confronted him.

And she lost her job. She was attacked.

Help unpack that for me. Was that overreaction or was that something that was useful?

WILLIAMS: They even took her dog away from her.

I mean, she suffered a complete evisceration of her public persona in the world. And she — this woman, Amy Cooper, obviously behaved in ways that I

find reprehensible. But I seem to find myself siding more with Chris Cooper himself, who said that he felt that the reaction was — it was just — it

was too much.

What happened to her was out of all proportion with what she had actually done. No one was actually physically harmed.

But this woman died a public death, metaphorically speaking. She was expelled from the realm of acceptable human beings. And I can’t kind of

overstate how terrifying that is and what that does to people and how that constricts the atmosphere of public discourse and the idea that even people

can be rehabilitated.

I want to be very clear that I don’t agree with the way that she behaved in the park whatsoever. And it does happen to a longer history of people

calling police to punish and disciplining, sometimes physically break black people for simply doing things that they don’t want to be done, for simply

being in the space with them.

So it taps into a pretty ugly history. But I don’t think that we want to live in a world where we all can become Amy Cooper.

ISAACSON: Would you say it constricted behavior like that? And you say that thousands of times.

I mean, I see it every day, where a white person will use a particular type of power and hurt or humiliate or do something that is basically racist.

Don’t we want to restrict that? And isn’t what happened to Amy Cooper just a warning signal to the rest of us to be more careful?

WILLIAMS: It’s certainly a warning signal.

I think that she should have — she should be held accountable for that. She should have ramifications for that.

Where I do keep struggling to understand our impulses is, why do we always have to take away someone’s livelihood for so many of these transgressions?

This was not something that she did at work. This had nothing to do with her performance at work.

This is something that she deserved to be called out on, and we need to have the behavior stop. But we seem to always go to the superlative of the

disciplinary action, which is that you must not be able to have a livelihood.

That’s chilling. So, one of the things I think about a lot in this discussion with cancellation is a lot of the pushback has been, well, black

people and marginalized people have always been getting canceled. So all that’s new is that white people are getting canceled, too, now.

That may be the case. I certainly am very sensitive to that argument. And I have seen the way that racism has worked throughout my father’s

professional life. I’m sensitive to that.

But I don’t think that the world that I want to create is one in which we are all rendered as vulnerable as the most vulnerable people used to be.

I’d much rather see a world where we can all be made as secure and as able to feel free to have a generous kind of response to our actions as white

people have traditionally been able to feel themselves to be.

ISAACSON: So, what should happen to people who truly transgress the bounds of racism, anti-Semitism?

WILLIAMS: Well, I think what has to happen is that we have to have a real understanding of what racism is.

These definitions are rapidly shifting now. So, in any moment when things – – when definitions are rapidly shifting, we have to give people a chance to catch up. We have only just gotten into a conversation where people are

widely accepting an idea of racism that’s systemic in nature, and not about the hatred that you have in your heart, as George Bush would have said.

That’s all to the good. We should have a more expansive understanding of all the ways in which inequality operates. But we also have to give people

who have spent 50, 60, 70 years of their time on this Earth thinking about reality in one way a chance to adapt to a new system of reality before we

immediately hang them out to dry.

So I think we have to understand what racism is. And if we’re going to go to an extreme, like what Ibram X. Kendi or what Robin DiAngelo says it is,

I think we have to have a chance for some counterargument.

And that’s where I try to push back.

ISAACSON: I’m going to ask a very philosophical question.

I know why I’m in favor of free speech, and you probably do know why you’re in favor. But explain to me, why is free speech a good thing?

WILLIAMS: Oh, that is a very philosophical question, because we don’t know what all the right answers are yet. We don’t know what the better tomorrow

will be until we try to articulate a vision of what our better tomorrow could be.

And that takes hearing from as many perspectives as we can possibly cobble together. And so, the more you limit what can be said before it’s even

uttered, the more you limit how many, like, stabs at getting us towards this better tomorrow can be heard and can be tested out and can be aired

out and exposed to the kind of debate that lets us know what’s worth keeping and what’s worth rejecting, I think we have to always have a kind

of humility and modesty.

And that modesty makes us want more speech. I think that marginalized people are most able to flourish in places and societies and spaces where

culture is free and experimentation is encouraged.

I think that people shrivel up and marginalized people always fare worse in highly restricted spaces. One of the responses I got that meant the most to

me was from a man who identified as African-American on Twitter, had a very small account with about 200 followers.

And he said, I’m not famous enough that anyone will ever ask me to sign an open letter, but no one’s ever explained to me how, as a black man in

America, my life will be made better with less ability to speak freely. No one’s ever explained it to me. So thank you for doing this.

And I took that very seriously and to heart.

ISAACSON: Thomas Chatterton Williams, hey, thanks for being with us.

WILLIAMS: Thank you so much for having me.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: And, finally, on the matter of singing freely, the Rolling Stones are back with a long-lost, never-before-released track called

“Scarlet.”

So this was originally recorded in 1974, featuring Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page on the guitar.

So here’s Mick Jagger and Jimmy Page now discussing why they’re releasing it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICK JAGGER, MUSICIAN: Especially now, at the moment, it’s good to do this kind of stuff.

JIMMY PAGE, MUSICIAN: It’s really great to have done it. It’s brilliant, what Mick has done with it.

But it’s also good to hear Jimmy Page flying as he was in the 1970s.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: “Scarlet” is out today. And it will be included on the upcoming re-release of the band’s iconic 1973 album, “Goats Head Soup.” That will be

in September.

Thank you for watching, and goodbye from London.

END