Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: AK-47 type assault rifle. It was purchased legally in the State of Nevada.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: After another mass shooting, Democrats face off in the second round of debates. We dive into the big issue of gun laws with a leading

voice, Connecticut senator, Chris Murphy.

And the White House-Middle East peace plan.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MADEES KHOURY, GENERAL MANAGER, TAYBEH BREWING COMPANY: We need to resolve the political issue. We need to go back to negotiating and resolving the

political problems.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: We hear from Palestinian businesses and from Washington’s man in Israel, Ambassador David Friedman.

Plus, a painful struggle for parenthood.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

FARAI CHIDEYA, JOURNALIST: Adoption is beautiful, the industry can be very ugly.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Farai Chideya speaks of heartbreak trying to adopt a child three different times and failing.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Democratic 2020 hopefuls are taking to the stage as CNN hosts the second round of debates from Detroit, Michigan. These presentations have the

power to win over the feel and to reshape the race. Indeed, the issue of race dominates the current climate, with their opponent, President Trump’s

apparent hate and fear campaign strategy.

As contenders battle it out, we’re going to delve into one of the big issues that once again is tragically making headlines, and that’s gun

violence. A deadly shooting at a Mississippi Walmart today, gunfire at a Brooklyn festival over the weekend. And in California on Sunday, a 19-

year-old man opens fire and kills three people at a Garlic Festival. He was killed by police. Two of his victims were children, one was barely a

teen, the other was just 6. Here is his heartbroken father.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ALBERTO ROMERO, FATHER OF SLAIN 6-YEAR-OLD STEPHEN ROMERO: They tell me he was in critical condition, that they were working on him. And the, five

minutes later, they told me that he was dead.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Now, a post on the suspect’s Instagram account referenced a White supremacist book just before the attack. His weapon, an assault-

style rifle, could not be sold in California where the attack happened, but police say it was purchased legally in next door Nevada.

Senator Chris Murphy is the Connecticut Democrat who has become a leading voice in Congress on the issue of gun control especially since the 2012

massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in his home state. I spoke to him on Capitol Hill.

Senator Murphy, welcome back to the program.

SEN. CHRIS MURPHY (D-CT): Thanks for having me.

AMANPOUR: So, in the wake of these terrible shootings, in the wake of Democrats trying to stake out who is going to be the opponent for President

Trump, we want to focus on this issue, particularly since essentially a child, a 19-year-old, adolescent, if you’d like, killed children over the

weekend in California. I mean, it does seem that this issue is simply not being dealt with no matter how exponentially worse the horrors get.

MURPHY: And I think it’s important to remember that, though much of the country plugs into this issue when there is a mass shooting or when there

is a high-profile incident of a child being killed, every single day in this nation about 90 to 100 people die from gunshot wounds. Now, the

majority of those are suicides, but we have a dramatic spike in suicides by gun death in this country as well. Many of the others are accidental

shootings and homicides.

So, this is a daily epidemic in this country and has enormous social cost. What we are lacking in this nation today is a political movement that is

strong enough to beat the gun lobby in the United States Congress, and that’s what we’re in the middle of building today. But what we already

know is that, on a state-by-state basis, states that have tougher gun laws, states that have universal background checks or states that require you to

get a permit before you buy a gun or states that ban semi-automatic weapons, have dramatically lower rates of gun violence, have dramatically

lower rates of gun suicides, there are less women that are killed by intimate partners with guns.

And so, this isn’t a question of having to guess what policies work and which don’t. We know what policies work and we now have to build them on a

national basis.

AMANPOUR: But can I ask you, because, obviously, all-over social media, there are all sorts of different interpretations of what happened. The

famous gun lobby chant is good guys need to have guns. Therefore, they will get to the bad guys. I wonder what your assessment is then, in this

case, the good guys, the security got there super-fast, within one minute. And yet, the gunman, a 19-year-old was able to kill three people and wound

many, many more.

MURPHY: So, there’s no evidence to suggest that this mythology, “A good guy with a gun is the best way to stop a bad guy with a gun,” is

actually true. First, let’s just take this. The states that have the higher percentage of citizens with firearms have the highest rates of gun

crime. If you have a gun in your home, that gun is exponentially more likely to be used to kill you than it is to be turned on an intruder.

If more guns kept countries more safe, then America wouldn’t be the country with the highest level of gun crime. We’d be the country with the lowest

level of gun crime. So, there’s zero evidence to suggest that is true.

The reason the gun lobby says, “Good guys with guns stop bad guys with guns,” is simply because it’s a marketing gimmick. It’s a way to sell more

guns, it’s a way to convince Americans that the only way to protect themselves is to arm up. In fact, the way to protect yourself is to make

sure your state or your town has gun laws on the books that stop dangerous weapons from being in the hands of potentially dangerous people. But that

is not what the gun lobby wants people to know.

AMANPOUR: You’ve talked about what the NRA wants, you know, what’s the result of all this stuff. But, you know, the midterms showed that gun

control advocates outspent the NRA and gun advocates. Isn’t there a momentum then for sensible gun laws to finally be in place?

MURPHY: Yes. There is this national movement building. And in the House, in 2018, 18 NRA A-rated incumbent members lost their seats and were

replaced by members of Congress who support tougher gun laws. And take a race like the Sixth District in Georgia where Lucy McBath, a gun rights

advocate lost her son to gun violence, ran in a district that had been Republican for decades, ran proudly on the issue of passing tougher gun

laws and won. Why? Because it’s turnout issue.

More people today turn out to vote in elections if they think they’re going to vote for somebody that supports things like universal background checks.

And that, frankly, was not the case four years ago or six years ago.

AMANPOUR: We’ve got a graphic up. We’ve got some bullet points that the – – that some of the Democratic candidates have on gun issues. And I want to know whether you are convinced that the Democrats standing for election are

really using this issue as a major issue in their campaigns.

MURPHY: So, I do. And I frankly think that the very fact that it hasn’t been a point of conflict and division in the Democratic field is evidence

of how far that we have traveled. In fact, almost all of the major candidates have put out plans on how they would tighten the nation’s gun

laws. They have made a big deal about those plans, but they haven’t gotten a ton of coverage in the press because they are all strong.

Every single Democratic candidate is running on universal background checks, on banning assault weapons. Many of them have other more specific

ideas like requiring permits in order to buy pistols. And so, it’s not, frankly, going likely be an issue in Democratic debates because they are

all on the same page. It will absolutely be an issue when it comes to the general election because swing voters, especially suburban voters,

especially voters living in these violent areas inside our cities, are going to demand that the next president of the United States clamp down on

gun violence.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you about what’s going on in response to the terrible devastating Sandy Hook massacre in your own State of Connecticut

in 2012. Many families feel that the best way to try to make a real point about banning this kind of weapons is to sue the gun manufacturers over

their aggressive advertising techniques. And we know there was a bushmaster ad, it has been taken down. But it was designed, according to

people, you know, to reinstate the manhood, perhaps, of people who felt disconnected.

There is a 2005 law called PLCAA, the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, which prevents gun manufacturers from being held liable. Is there

movement on that? Is the idea of trying to pierce a hole in PLCAA a good idea, a constructive idea that will have a meaningful effect?

MURPHY: So, today, the maker of a toy gun has more liability for that product being defective than the maker of a real gun, which is absolutely

absurd. Yes, this is clearly on our list of the pieces of legislation we’d like to overturn if we get an anti-gun violence majority in the House and

the Senate.

But I will also say, it is a sign of how things have changed. This law passed back in the 2000s when, frankly, the gun industry got anything they

wanted from Congress. Today, the gun lobby can’t get anything from Congress.

In fact, when Republicans controlled the House, the Senate and the White House, the gun industry had a laundry list of things that they

wanted and they couldn’t get a single one of them brought up for a vote because even Republicans now know that they are going to lose votes if they

do the bidding of the gun lobby.

AMANPOUR: But I want to ask you another issue that obviously is dirtying the current climate, and that is the issue of racism. You, yourself, this

week said in a tweet, “I am unfollowing the president of the United States today on Twitter because his feed is the most hate-filled, racist and

demeaning of the 200-plus I follow and it regularly ruins my day to read it. So, I’m just going to stop. I can’t believe I just typed that.”

The president says he does not have a racist bone in his body. Do you, however, believe that he’s doubling down on what he feels is a proven

campaign strategy to use, divisions between races, to win?

MURPHY: Now, I think it clearly is a strategy. I think he looks to the 2016 election where he, you know — I mean, his agenda was racist. I mean,

he claimed that every Muslim in this country was a threat to the United States and he sees he was awarded for that in the general election.

And so — especially now that his policies, his health care policies, his immigration policies, his tax policies are widely unpopular in America,

he’s seeking to go back to that strategy he employed in 2016 to try to divide us and make enough people scared of people of color that they come

out to vote for him in large numbers. I don’t think that’s going to work, but I also think we all have an obligation to call out his racism

regardless of whether it’s good politics or not for us.

AMANPOUR: And I guess, of course, the president would reject this, his allies would reject this. But it’s not an accident that many of the latest

shooters are White supremacists or have leanings that way. The 19-year-old in California referenced on his Instagram a major White supremacist text.

Do you think it’s got a trickle-down effect or is this just the way terrorism is going now?

MURPHY: So, I have always thought that the silence of Congress on the issue of gun violence has been an implicit endorsement, but I also believe

that people who stoke division in this country, who trade in racist tropes, are making it more likely that individuals like this young man are going to

turn their inner demons into an act of shooting.

And so, the president has the most responsibility given that he occupies the most significant bully pulpit. And instead of trying to calm the

divisions in this country, he is trying to exacerbate them.

AMANPOUR: It’s really fascinating times. Very serious times. Senator Chris Murphy, thank you very much for joining us.

MURPHY: Thanks a lot.

AMANPOUR: Now, as Democrats gear up to try to take back the White House, President Trump is digging in trying to hold on to a second term. One

thing he really wants to accomplish, the deal of the century for peace in the Middle East. Trump’s son-in-law and senior advisor, Jared Kushner, is

traveling to the region right now to promote the economic plan, which specifically is a $50 billion investment fund for Gaza and the West Bank,

which Kushner proposed at a summit in Bahrain last month.

In a moment, we’re going to hear from the U.S. Ambassador to Israel, David Friedman.

But first, many Palestinians and foreign policy experts criticized the proposal, saying that it’s meaningless without a political plan.

Correspondent Michael Holmes, went to the small Palestinian Village of Taybeh in the West Bank to seek out the views at a local brewery. And he

discovered firsthand the challenges and the red tape facing this family- owned business.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHAEL HOLMES, CNN INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: The Taybeh brewery in the West Bank is a Palestinian success story, producing 600,000 liters a year

shipped locally to Israel and to 15 countries from Morocco to the U.S.

It’s a family-owned enterprise started 25 years ago and now run by a second generation of Khoury family brewers. For all of those 25 years, the family

has negotiated myriad obstacles, just getting their brew to markets abroad.

It’s a windy day here in the West Bank, but we wanted to come up here to show you the water tanks. Because one thing you cannot make beer without

is water. And water has always been a big issue in the West Bank. Israel controls the water supply. Taybeh beer, like all Palestinians, they get an

allowance. Once that allowance runs out, that’s it. If you want more, you have to pay for a tanker to get a shipment in.

KHOURY: At the moment in the summertime, that is when we feel the water shortage, that’s when you want to brew more beer and that’s when we have

water coming once a week.

HOLMES: Under the 1995 Oslo II Agreement, Israel retained ultimate control over water resources. But COGAT, the Israeli Military Authority

responsible for civilians in the West Bank says the brewery is in a Palestinian controlled area and the Palestinian authorities are

responsible. In essence, when it comes to water issues, both sides blame the other.

The latest attempt to untangle the Israeli-Palestinian conflict took place in Bahrain a few weeks ago. The U.S. president’s son-in-law, Jared

Kushner, unveiling an economic plan for Palestinians, one criticized by many for rehashing old ideas, being vague about implementation and putting

off political solutions for later. Madees Khoury and her family say economic dreams are pointless without a political settlement first.

KHOURY: We need to resolve the political issue. We need to go back to negotiating and resolving the political problems and then talk about

economy and economic solutions.

HOLMES: So, when you heard that plan, what did you think?

KHOURY: I just brushed it off.

HOLMES: Instead of aid or vague investment promises, Madees Khoury says much could be achieved by easing of Israeli restrictions. Taxes, red tape,

rules and regulations, she says, are for Palestinians only.

The first roadblock, a literal one. The Israeli checkpoint between the West Bank and Israel.

KHOURY: If you would look at the map, you would see the distance between our town, Tiber, to Jaffa Port, which we use to export. On the map, it’s

an hour and a half drive. In reality, it actually takes three days if everything moves smoothly, which it never does.

HOLMES: Israel’s COGAT says those claims are “not consistent with reality.” The checkpoint transit times for goods are down to an average 90

minutes and further improvements are planned. The Khourys disagree. But back in Tiber, the family will continue to brew and wait, their business, a

microcosm of the broader economic hurdles that confront the Palestinian economy. Hurdles the Khoury family say won’t be cleared without there

being that political settlement, something that looks more remote now than ever before, although Madees’s father, Nadim, is the eternal optimist.

NADIM KHOURY, OWNER, TAYBEH BREWING COMPANY: Some day we will be free. We have high hope in the future. Nothing left for us except the high hope.

HOLMES: Michael Holmes, Taybeh in the West Bank.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

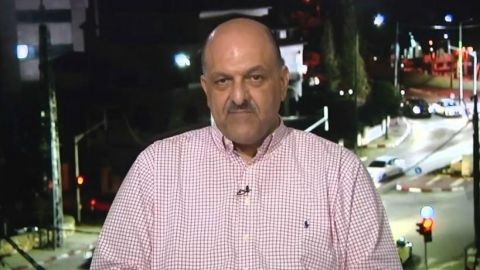

AMANPOUR: And listening to that is Sam Bahour. He’s a Palestinian- American businessman who is very familiar with all these realities and with the Khoury family. And he’s joining us now from Ramallah.

Mr. Bahour, welcome to the program.

You know, we heard from the people doing the work there, the actual business people in the brewery, that, yes, money and economic incentives

are great, but they need a political — they need a political solution. Why is it not OK to just take this money that’s being offered when so much

of it is needed?

SAM BAHOUR, BUSINESSMAN LIVING IN RAMALLAH: Actually, there’s no money being offered to date. What we heard was an announcement of an economic

plan of $50 billion. Only 27 allocated to the West Bank and Gaza. Half of that 27 being grants, half of it being loans. And the grants, not U.S.

money, but supposedly Arab money. All nice words, nothing has materialized to date.

What I would say after being here for 25 years, after moving here from Youngstown, Ohio, working in economic development is it’s a grand plan.

It’s great to do economic development in Palestine, but there’s a reason, a real reason why it has not happened to date. Because of 52 years of

Israeli military occupation, the restrictions that are placed on us make economic development unable to be addressed in a serious way. So, I have

no idea how an economic plan without putting the political parameters in place has even a chance to succeed.

AMANPOUR: Do you expect some of those questions that you’re raising now could be addressed with Jared Kushner’s current trip to the Middle East?

You say not a single dollar has been committed. But clearly, he’s out there now trying to raise that money and perhaps trying to ask the Israelis

to, you know, do what you think is necessary, in other words, reduce the red tape, you know, allow an economic lifeline to exist.

BAHOUR: He may raise the money, but the issue is not only money. This is not an economic deal for a real estate project. He and the administration

are undermining all of the legal found foundation that is the scaffolding for a peace process to actually result in a two-state solution where both

Israel and Palestine can live peacefully.

Trying to create some $50 billion carrot without a political parameter is like trying to build a building in New York without asking

what are the laws that apply or what are the building codes. We want to build a building. We actually are building a state. But to do that, we

need to understand the laws that applied and order the building codes. Where are we able to build our state?

Because up until now, Israel has not let any land be available for a real state building. They control what we can and cannot do. I as an

individual have documented 101 restrictions that have been placed upon us. If Mr. Kushner can actually get those 101 restrictions removed, that would

be great, but we’re not going to pay a political price for our human right, because it is a right.

Including the right for development. I can’t understand how the U.S. feels that it can develop Palestine without the Palestinians, without the

Palestinian leadership. Without political agency. there is no political plan and there is no economic plan.

AMANPOUR: So, let me ask you about Palestinian leadership. Obviously, we know the Palestinian authority boycotted the talks, they didn’t go. But I

asked the Palestinian prime minister, you know, why he would punish, or would he punish, as it was suggested, Palestinian businessmen, who went to

the Bahrain conference, the summit. And he said no, no, no.

But in fact, at least one was punished. They did arrest and then release the businessman, Salah Abu Mayala. And a security official told CNN that

what they have done is tantamount to betrayal and the Palestinian law punishes those who betray their homeland and the Palestinian people.

So, I mean, even if Palestinian businessmen wanted to engage with this economic plan, the leadership is not allowing them.

BAHOUR: I think it’s inaccurate to call the Palestinians as boycotting the economic workshop. They were not invited to start with. Thus, the notion

that you can develop Palestine without Palestinians officially is child’s play.

They did find five Uncle Toms. We’re just like any other society, we have our Uncle Toms, and they found five individuals. And I think on the stage

in Bahrain, the person on the panel was asked, what is your business in Palestine. I think he was asked four times and could not answer. The real

Palestinian private sector are the ones who actually produced a statement against the economic workshop before the Palestinian leadership even made a

public statement about it. So, the private sector here is very understanding of what it takes to build an economy.

AMANPOUR: OK.

BAHOUR: We have skin in the game. We’ve been trying to do this for a while. We know exactly what’s blocking it. And it’s not only the Israeli

occupation, but we need to call it for what it is today, the U.S.-Israeli occupation.

AMANPOUR: Right. Well, let me ask you this, because you bring up the U.S. and Israel. And you have written quite interestingly stating the obvious

that the United States, the Trump administration is very pro-Israel. Its decision to move the embassy from Tel Aviv, its decision to suggest

annexation of the Golan was OK.

Its reducing or remove funding of the Palestinians clearly show that it is very pro-Israel. But you say that it’s driving off the cliff to the

detriment of Israel. Can you explain that?

BAHOUR: Yes. I believe that Israel is drunk on power, and they are about to fall off the cliff. The cliff has a name to it. It’s called the two-

state solution. If Israel falls off the cliff, they will find themselves in a one-state outcome. I don’t even want to call it a solution.

Having said that, the only friend of Israel’s that can actually stop the car and the driver from driving drunk is the United States. Instead of

stopping the car, the United States has jumped into the driver’s seat and put its foot on top of the Israeli foot, both on the accelerator. So,

Israel is just moving faster and faster under the Trump administration to find out it’s forced upon itself and upon us a one-state reality.

And the fact of the matter is, we Palestinians can live in a one-state reality. My question to my Jewish Israeli neighbors, can they? And I

don’t think they can given — especially after passing this nation state law which basically says Israel is exclusively a Jewish homeland.

If that’s the mindset of Israel today, they are taking themselves to a detrimental step of potentially putting the state of industrial itself in

danger.

AMANPOUR: Well, I’m —

BAHOUR: The U.S. has a role to play, a legal role to play. They’ve always been pro-Israeli. We know that. But never have we had a U.S.

administration to adopt an Israeli an extremist right-wing agenda and implement it on the ground. And that’s what we have today.

AMANPOUR: Well, I’m going to turn now, Mr. Bahour.

Thank you for joining me from Ramallah. I’m going to turn now to the co-architect of the Trump administration’s plan and his former

attorney and close friend and ambassador to Israel, David Friedman. And he’s joining me from Tel Aviv. And this is an exclusive interview.

So, Mr. Friedman, thank you for joining me.

Look, you have just heard some quite harsh analysis of the economic part of your plan. And particularly, I’m interested in getting your reaction to

the last thing Mr. Bahour said that if this support of Israel and if this, as he put it, driving off the cliff of a two-state solution happens, is to

Israel’s detriment, how do you explain that? How do you respond to that?

DAVID FRIEDMAN, U.S. AMBASSADOR TO ISRAEL: I don’t think anyone responsible in Israel is pushing for a one-state solution. So, I think his

concerns are — you know, I understand his point, but I don’t think there’s really a serious political movement in Israel for a one-state solution, and

I don’t think any of the acts that Israel has taken or we’ve taken over the past two years is driving us to that point.

AMANPOUR: So, could I ask you then, Mr. Friedman, to just state it —

FRIEDMAN: I respectfully disagree.

AMANPOUR: OK. I understand. Sorry. We’ve got a delay. I’m sorry to interrupt you. Are you saying that the Trump administration and the

Kushner peace plan and your involvement in it absolutely still believes and upholds the notion of a two-state solution?

FRIEDMAN: Look, we haven’t used that phrase, but it’s not because we are trying to drive towards a one-state solution. The issue we have is

agreeing in advance to a state because the word state conjures up with it so many potential issues that we think it’s — it does a disservice for us

to use that phrase until we can have a complete exposition of all the rights, all the limitations that would go into Palestinian autonomy.

We believe in Palestinian autonomy. We believe in Palestinian, civilian self-governance. We believe that that autonomy should be extended up until

the point where it interferes with Israeli security. And it’s a very complicated needle to thread.

AMANPOUR: You say autonomy. They obviously say independence. And the reason I’m talking about it is because it goes to the heart of the plan

that you are trying to get the world on board, and including the Palestinians on board.

You saw the story, the report from, you know, a real live Palestinian business, the brewery. And they say, “Look, you can’t bribe us, you can’t

fob us off, you can’t tempt us with a carrot of $50 billion without answering the obvious elephant in the room, and that is the political

settlement and political parameters and political solution has to come with or as part of it.” Where are you on that part?

FRIEDMAN: We don’t disagree at all. I think we’ve made the point over and over again that the economic solution goes hand in hand with a political

solution. But let me explain a little bit about a political solution. In order to have a political solution, you need political institutions. You

need a transparent economy.

You need the rule of law. You need certain freedoms, freedom of the press. You need a justice system. You need to stop concentrating all the

Palestinian wealth and the political elites. That’s part of what Bahrain was about, trying to help the Palestinians create the institutions

necessary for statehood.

Because let’s be clear, OK, the last thing the world needs is a failed Palestinian State in between Jordan and Israel. And right now, the

Palestinian government is so weak, they have no answer to Hamas. They leave that to Israel to take care of. They have no answer to Islamic

Jihad. They leave that to Israel to take care of.

And what can’t happen here? The one thing that can’t happen is the Palestinians obtain independence and in short order, this becomes a failed

state controlled by Hamas, Hezbollah, ISIS or al-Qaeda. I mean, that is an existential threat to Israel, it’s an existential threat to Jordan. It

simply can’t be.

So, with great sympathy for all the issues, the red tape, the bureaucracy, it goes both ways by the way. And it’s not quite as bad as the

Palestinians say and it’s not quite as good as the COGAT says. I mean, there’s lots and lots of stories here not worth going into.

But the point is we need to help the Palestinians create the institutions for autonomy and self-governance. The other I would say — you know, what

I’m saying is nothing new. If you listen to what Yitzhak Rabin said to the Knesset in 1995. He was a great Israeli hero. He gave his life for the

cause of peace.

And when Yitzhak Rabin spoke to the Knesset to sell the Oslo Accords, he also was unwilling to use the term Palestinian State. He

preferred words like autonomy and self-governance.

Because that word, it just creates expectations that I think cause everybody to kind of retreat to their corners, and it’s not helpful.

AMANPOUR: Mr. Friedman, look, I mean the notion of a Palestinian State is kind of enshrined in international law right now and in all the blueprints

for peace. It’s very interesting to hear you question the use of that very word which is the fundamental reality of any people’s aspirations.

I would just say it was at the height of the Oslo process that the Palestinian economy boomed, that unemployment was at a record low and that

there was a great deal of success between the two entities. And I would say, also, that other prime ministers, for instance Prime Minister al-Mulk

and others who dealt with Mahmoud Abbas and the authorities say that he must be the partner for peace, he wants to be and there is no other.

So if you don’t think they’re up to it, there’s nobody else to deal with. And I guess I’m asking you this because I wonder what you have asked your

friends in the Israeli government — and you were just unusually at a cabinet meeting of Benjamin Netanyahu’s. What have you asked them in

return for all the things that you’ve delivered to the Israelis?

I mean surely you negotiated. What have you asked them in return for moving the embassy, for agreeing with the annexation of the Golan Heights?

FRIEDMAN: Well, look, we spent lots of time speaking with the Israelis about improving conditions in the west bank in Gaza, a lot. There’s just I

think two days ago the prime minister announced that the government was granting building permits to Palestinians to build in area C, something

that hasn’t happened in quite a while.

We care very much about the Palestinian people, about improving the quality of life. We work with them extensively on it. We think it’s good for

Israel and good for the Palestinians.

And we take no — I’m sorry. I’ve lost the feed. But we take no — it’s a matter of real significance to us and importance to us to improve the

quality of life.

And just to be clear, we want the Palestinians to have autonomy. We want the Palestinians to govern themselves.

The security issues are somewhat daunting The world has changed a lot in the past 10, 15 years.

The last time people took a hard look at peace making, Gaza was not threatening to Israel, Lebanon was far less threatening to Israel. Syria

obviously was not the catastrophe that it became. Iraq was less threatening and Iran was much less threatening to Israel.

So the capacity of Israel to take risks has changed. The facts on the ground have changed. And we need to develop a plan for 2019.

AMANPOUR: So Mr. Friedman, ambassador —

FRIEDMAN: It was all — yes?

AMANPOUR: Sorry to interrupt you but we’re just running out of time. I mean as you know, every single piece or plan in visages Israel being in

total control of security, whether it’s the sea of Gaza, whether it’s the eventual border on the other side, whether it’s the airwaves, those — the

airspace, all of that is Israel’s to patrol and to man.

I guess I wanted to ask you, in light of this security issue that you bring up, you have said that — in fact, you said just recently, under certain

circumstances I think Israel has the right to retain some, but unlikely all of the west bank.

I mean that is pretty far out, so to speak. Whose — what do you envision? How much of the west bank and under what circumstances?

FRIEDMAN: Christiane, that’s not far out at all. If you go back to our undersecretary of state during the Johnson administration, who represented

the United States in the negotiation of the cease-fire to the six-day war – –

AMANPOUR: Yes. But sir, that was before the engagement. Sir, that was before the engagement between Israel and Palestine in the Oslo process. I

just want to know what circumstances and how much?

FRIEDMAN: Oh, I don’t know. I mean that was — the question was put to me hypothetically. How much — look, Israel has not presented to us any plan

to retain or annex any portion of the west bank, and we have no view on it at all right now.

My view was a legal one, whether Israel has the legal right to retain under some circumstances some portion of the west bank, the answer is

yes. But it’s a hypothetical question and more importantly it’s a legal question.

And this is not a conflict that’s going to resolve — going to be resolved in a court of law. It has to be resolved diplomatically. So I think much

more was made of that than it really is worth.

AMANPOUR: All right. I just want to show some video because it’s interesting. It’s you with a sledgehammer just recently, sort of breaking

ground, if you like, of that tunnel that runs under a Palestinian village in East Jerusalem, and just ask you to comment on why you would be doing

that, why you support and even donate to settlements which are considered illegal under international law, and the U.S. has policy that the

ambassador to Israel should not visit settlements in the west bank.

You obviously — you financed Batal, you visited Ariel, why do you think you can keep doing these things in contravention of U.S. law?

FRIEDMAN: Christiane, you’ve made about six assumptions there. Every one of which, respectfully is wrong.

First of all, I’m the United States ambassador to Israel. My area of responsibility extends to Israel inside the green line to the west bank and

to Gaza. So it’s my area of responsibility to go anywhere. That is the United States policy.

AMANPOUR: No, I said the settlements.

FRIEDMAN: The settlements are part of the west bank. It’s part of my responsibility. Anywhere in the west bank is under my area of

responsibility.

Number two, that was an incredible heritage site. That was a discovery of the pilgrimage road from the bathing pool at the bottom of the ancient

temple, a road that went all the way up to the temple.

It was a road where Jesus walked, where people has great religious and historical significance. It was an incredible archaeological discovery,

discovered by secular archaeologist and it’s a matter of great interest to the American people.

Many, many tens of millions of Americans found this very interesting. And I was attending the opening of this great incredible archaeological

discovery, which by the way was so far below the homes of the residents, 60, 70 feet, had no impact on them whatsoever.

AMANPOUR: All right. Well, just as some would ask why do that at a time like this. But listen, you’ve answered the question. We’re grateful that

you’ve been with us tonight and thank you for joining us Ambassador Friedman from Tel Aviv.

So we turn now to an issue that links all of us and that is motherhood. One of the great joys and challenges in a woman’s life, and it’s wrapped in

societal pressure and biological challenges.

Women are scrutinized for how, when and if they choose to have children at all. Imagine choosing adoption, completing the process three times, once

even taking home a baby only to end up without the child and $50,000 out of pocket.

That’s what happened to journalist Farai Chideya. She’s opening up about the emotional rollercoaster of the adoption system in her new piece that is

found on Zora.medium which is for women of color and it’s titled, “Excuse Me, May I Raise Your Child.” She sat down with our Michel Martin.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN, CORRESPONDENT, NPR: Farai Chideya, thank you so much for talking with us.

FARAI CHIDEYA: I am so glad to be with you.

MARTIN: As I understand it, 140,000 children are adopted by American families every year, and African-American children are disproportionately

represented. Half a million children are in foster care in the U.S.

So you look at those numbers and you might think why isn’t there — why isn’t one of those kids for me?

CHIDEYA: Of course I did, or else I wouldn’t have entered this. And I also thought that it would happen relatively quickly.

So I also made some life decisions about — I was trying to optimize my life to be someone who could work from home a lot. I sought out jobs that

were very flexible, didn’t seek to maximize my earnings, sought to maximize my time to be with a baby and made a lot of life choices based on

assumptions that didn’t turn out to be true.

But I will say in all honesty, this experience has broken me many times, but also I feel like I don’t think it was fate. But I think sometimes the

universe gives you assignments. And it was my assignment to understand the adoption industry.

Adoption is beautiful. The industry can be very ugly.

MARTIN: But in your case though, when did you realize, you know what, this is harder than I thought it was going to be.

CHIDEYA: Well, first I went to the foster care system. And I believe that I came to the foster care system at a time when they were really

transitioning from having more young children, not babies but young children, who were adoptable.

Meaning that they had the parental rights terminated and they were up for adoption, to the reunification model that says we will look for

any extended family and try to match the child with that.

Because I entered what’s called the map training program to become certified as a foster parent with the promise that there were children that

could have been adopted from that agency. I knew two different families who had adopted from that agency.

And then by the time I was done with the training and got my little certificate, they were like, oh, yeah, no baby. There’s no children you

can adopt. You can foster.

And fostering is beautiful but it comes with the risk of reunification, that you will have a child in your home that will later be taken back. And

I am — to be honest, Michel, still struggling with whether I’m willing to do the foster to adopt.

MARTIN: So but then you went the private agency route and that’s when things kind of got really —

CHIDEYA: Awful.

MARTIN: Awful.

CHIDEYA: Yes. I narrowed it to three agencies. One agency went out of business and the other one told me straight up, “We can’t place enough kids

with single women. Your best bet is not to work with us.”

And then this agency that promised, they said, “If you want a black child, it will take an average of six months. If you want a white child, it will

take an average of 12 months.” So at the same time that their contract says we don’t guarantee you a baby, they will tell you to your face that

you will get a baby quickly.

MARTIN: What happened?

CHIDEYA: So after going through this adoption consultancy and choosing an agency which said, oh, you should get a black baby within six months, I

didn’t do all my homework and look at how restrictive their contract was, but there were several months of training and courses and things like that.

And then the first time I was matched with a family — this is an open adoption system. So I drove to another state. I met a pregnant young

woman who already had two children.

I met her boyfriend, her mother and her grandmother. And they were living in an intergenerational household.

And they seemed like very lovely people, but the boyfriend did not want this to go through. He was very kind of offish in our first meeting.

MARTIN: Was he hostile?

CHIDEYA: He was not hostile. Like I said just sort of like —

MARTIN: You could tell something is not right?

CHIDEYA: So yes. But what happened then was that when she went into labor and my mother and I went to the hospital, he straight up told me and my

mother, “I don’t want this adoption to happen.”

He hadn’t said that before. He had just been distant and a little cold.

But he was like, “I wish I could keep this baby. I don’t have the finances, I can’t keep the baby alone, but I want this child.” And he

basically was begging me to — there was nothing I could do if the mother wanted to keep the child.

But I think what happened was that the young woman’s mother wanted her to give up the child. She probably felt torn. He wanted her to keep it —

them to keep it.

And so I take this baby out of the hospital, beautiful boy. I named him for my grandfather who I loved very much who has been dead for some time.

My mother is over the moon. This is her first and only grandchild. Still she has no grandchildren.

And then let me back up. I told the social worker, this young man wants to raise his child. Isn’t this a problem? And they were like no.

MARTIN: So you took the baby home and —

CHIDEYA: I took the baby actually to a vacation rental because there’s this thing called interstate compact. So I couldn’t take the baby to my

house yet.

But I had the car seat and the toys and the outfits. My mother was there. Friends came from out of state.

And this was supposed to be like, oh, it’s a week until you sign this paperwork to take the baby out of state. So I was not in my house, but I

was in a beautiful setting by a lake with this baby, and it was like all the dreams were coming true.

And then I get this call. And they said, oh, why don’t you bring the baby back to us? I was like, why don’t you come pick him up?

MARTIN: I just can’t picture what it was like for you —

CHIDEYA: I was just crying.

MARTIN: — to have this baby —

CHIDEYA: I cried for like —

MARTIN: — taken from you after you had waited and thought this baby was your baby.

CHIDEYA: I cried for a day. And when I mean — I mean I cried for months.

But when I say I cried for a day, I cried when they picked him — I cried when they called.

I cried when they picked him up. I cried driving back to my home state. I cried when I dropped my mother off at the train station, and I just kept

crying for 24 hours. Just almost hysterical crying.

I want to make it clear that the parents are not to be demonized. They were within their legal rights to revoke the adoption but they were also

within their moral rights.

And it took me a long time to understand that but I don’t blame them. I blame the agency for poor counseling and I felt betrayed.

MARTIN: Can you put into words what that feels like?

CHIDEYA: I felt gutted, cheated, abused by this system, not by the family, and angry. You know, I think it’s taken a lot for me to process my anger.

MARTIN: And then you went through this two more times?

CHIDEYA: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean two more times —

CHIDEYA: Right.

MARTIN: — you thought that a baby was yours.

CHIDEYA: Right.

MARTIN: Two more times. What happened? Both times the parents changed their minds?

CHIDEYA: Well, yes, both times the parents changed their minds. Very different circumstances.

So in the first circumstance I have met the family. Same was true in the second circumstance but I never saw the baby because I mean I knew

something was going wrong.

So the really heartbreaking situation there was that this woman had two children and her son offered to drop out of high school so they could keep

the baby. And that began to bring me into a moral alignment of understanding that these women were being betrayed by the promise of the

American dream.

Like why are we the only country of developed nations that doesn’t have a parental leave policy, that doesn’t have child care.

MARTIN: And then what was the third time?

CHIDEYA: The third time was really the straw that broke the camel’s back, where there was a young woman who had had several children. I went to the

hospital and then they tell me that she’s already revoked a previous adoption for another of her children.

So wouldn’t that be relevant information? When I finally cut off ties with the agency, I said you claim to provide excellent service to the adoptive

side and to the birth side — birth parent side, but you couldn’t tell me until I showed up at the hospital that she had revoked a previous adoption?

That’s information I should have. And I can’t blame her for wanting to raise her child, but she had a much heavier lift. She was living in a

motel with her children by the time this baby was born.

MARTIN: There are some who might argue that it would have been in her best interest and the child’s best interest for you to have this child to raise.

CHIDEYA: Right. No, and I’m not even going to argue on that point. Family is not just about logic.

Frankly, in America, if family was about logic, there would be even fewer children than we have today. And so do I think she was logical? No. Do I

think she acted out of love? Yes.

It is only the fates that will determine whether she made the right choice or not, and I do think both the number of children she had and the

circumstances she was in, you could certainly say logic would have dictated that perhaps it would have been a good idea to give up her child.

But I mean if there’s one thing I’ve learned, I am only in so much control and also I can only judge based on what I know, and there’s so much I don’t

know.

MARTIN: To talk about another sticky issue here. The cost.

CHIDEYA: Oh, yes.

MARTIN: I mean you say in the piece that it was at least $50,000.

CHIDEYA: Well, first of all, it’s not always that expensive. here are agencies that charge much less. And there are systems to get charitable

subsidies.

But also one of the reasons this was so high is that the agencies have a contract that’s airtight, you won’t get your money back. And the longer

you stay, the more you have to renew home studies, the more you pay expenses for the birth mothers, the more you pay — so basically part of

the cost I paid was that I stayed in the game so long.

MARTIN: Is there any part of you who feels that you were scammed? And if so, by whom? Because I can see —

CHIDEYA: I wouldn’t go so far as to say scammed. I would say — maybe this is a polite way of saying scammed, I was took.

I was took by the rhetoric. I did not read the contract in the way that I would today.

I would say to anyone considering adoption, read that contract carefully, ask them for alterations if you need to or be aware that you may be put

into a system of perpetual upselling to add more and more money to stay in the game.

I mean just because an agency is licensed doesn’t mean that you know the full story. And another thing is that there’s virtually no federal

regulation.

This is done at the state level. There’s all different rules and there’s no database that will tell you how many failed adoptions an agency has had,

how many negative outcomes. That is what we’re really missing.

I would advocate that in this country we need transparency about contracts and transparency about failure rates. There are many different

adoption, watch dog groups, but there’s no single federal entity that’s doing this watch dog work.

MARTIN: I was going to ask you that. What do you think should happen as a result of what you have now learned?

CHIDEYA: Well, first of all, we just have to reform the nature of how we treat families, not just women, not just babies, but families. We do not

provide parental leave.

There is a bipartisan majority of Americans who want there to be a parental leave policy and we don’t have one. Canada, a woman who gives birth, gets

15 weeks paid.

Why are we out in the wilderness, America the great? Why are we not supporting families?

So first of all, we have to top to bottom look at why we or not supporting families. Because it means more of these women who are putting their kids

up for financial reasons wouldn’t have to put their kids up.

And then women like me who are career women who worry, OK, if I step off the treadmill, I’ll never get back into the lane. We would have more of a

cohort of women who are able to take leave.

I think that America is falling behind other developed nations in what we offer families. Fertility rates are declining which means there’s evermore

desperation for adoptable children, particularly babies.

And we’re kind of going into a spiral that is really about how we’re not supporting families overall.

MARTIN: There are those who would say, if you’re not willing to interrupt your career to have a child, then maybe you shouldn’t.

CHIDEYA: Well, no, it’s not about interrupting. It’s about ending.

I know people who have had to switch careers entirely because their careers ended when they had a child or children and then they had to start a whole

new career. And that’s just part of the playing field. So whether I was overly fearful or not, there’s a lot of evidence that you are viewed as

lesser than.

MARTIN: And do you think race factors in here?

CHIDEYA: Well, I mean I had a woman say to me once that she was a white adoptive mother of a black child. And she said that the birth mother told

her she preferred a white woman because she felt her child would get a better life experience being raised by a white woman, financially and

socially.

So perhaps. But I don’t think the problem was in the matches with the women. The problem was the women I was matched with didn’t really want to

give up their kids and that the counseling was poor.

I believe there are black women who would happily match with me. I do think it’s much harder for single women. It’s much harder for single

women.

And in fact, in some states it’s legal to say that I only want a Christian married couple. Some adoption agencies can be that specific.

MARTIN: That is just legal?

CHIDEYA: Yes.

MARTIN: Well, in fact, we’ve seen some research that suggests that there’s a growing number of people who support the idea that a lot of people should

be excluded from adoption, whether it’s because of race or religion, or sexual identity.

CHIDEYA: Yes. I mean there have been laws in Texas, I believe Tennessee. There’s several states in which, especially LGBTQ people, but sometimes

even single people and non-Christians across the board can be prevented from adopting from agencies that work with the state.

So what I’m trying to be clear about is that the state says that it has a need to place children in homes, but it’s allowing agencies that they

contract with to cherry-pick and exclude large numbers of people. And one of the complicated things that’s happening is in our era of rising

xenophobia — there’s a great research institute, PRRI, the Public Religion Research Institute, it’s finding that more and more Americans are actually

supportive of service denials if you say it’s my religious belief that I want to not serve atheists, 24 percent of people believe that, don’t want

to serve LGBTQ people, 30 percent believe that.

Fifteen percent say, if I don’t want to serve African-Americans, I shouldn’t have to. So this is part of our cultural moment of — sadly some

of the issues turning up in adoption are also issues reflected in the national mood.

MARTIN: Having written this piece, how do you feel?

CHIDEYA: I feel liberated. I’m still sad in many ways.

But I also feel like I’ve been carrying around this little hot, steaming nugget of pain, and I’ve gotten the most beautiful notes from so many

people. And whatever happens next, I believe that I will have given people food for thought, and hopefully we as a nation can pull it

together and make this is a truly more family friendly country.

MARTIN: Farai Chideya, thank you so much for talking with us.

CHIDEYA: Thanks, Michel.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: What a heart-wrenching story. But that’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END