Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, four hundred years ago, a ship carrying more than 20 enslaved Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, starting the long and painful history of slavery here in America. The “New York Times” Magazine is marking this anniversary with the groundbreaking 1619 Project. It’s a collection of articles, essays, poems, and audio series that challenges us to rethink this ark history. Veteran Journalist and Writer Linda Villarosa is a contributor to the project and she says myths about racial differences are still believed by doctors today, effecting the medical treatment that African-Americans receive in some cases. And she sat down with our Walter Isaacson.

WALTER ISAACSON, CONTRIBUTOR: This is an amazing journalistic project, the 1619 Project, about the time slavery began in America in the “New York Times.” Explain to me how it came about and what it’s supposed to be doing.

LINDA VILLAROSA, CONTRIBUTING WRITER, NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE: So 1619 was the year, in August 1619 actually, when the first enslaved person came to America in Jamestown, Virginia. So the project in the “New York Times”, it started as a magazine piece to look back at how slavery, 250 years of it, had affected the structures of America and how they’re still present in our everyday life. And so then it expanded beyond just the magazine to the newspaper and to the “New York Times” daily podcast, and as a curriculum for schools and school teachers to access.

ISAACSON: You’re a health writer. So you write about things like the view of African-Americans’ health back then, but you even connect it to today. Tell me about Save the Lungs.

VILLAROSA: So the lung issue is really interesting. There’s a machine that’s used in current medical practice called the spirometer. So a couple of years ago, I had bronchitis so my doctor was trying to see if I was getting better. So I breathe into this machine to study my lung capacity. So for this piece that I wrote in the 1619, I look back at the history of the spirometer. So the spirometer was used to prove that African-Americans had inferior lungs, to both justify slavery but also to say slavery was beneficial to enslave people because all that exercise and the forced labor was building up the lungs. So then I thought back to the present, I thought there’s a race correction in the machine. And I’m wondering did my doctor put in my race, did this affect the treatment I got because the machine correct for 10 to 15 percent I guess call it inferiority in black people’s lungs. And the idea that Samuel Cartwright, this doctor, who really believed in the worst of racial myths, was the one who hat sort of set the stage for the use of this machine in America and that the history has traveled through centuries is alarming.

ISAACSON: But Thomas Jefferson does it as well.

VILLAROSA: And Samuel Cartwright probably got his ideas from Thomas Jefferson. So in Thomas Jefferson’s notes on the State of Virginia, which was really used to format laws and for guidance for the country at the time, if you read it, and it is a little bit of a throw away, what he says about the lungs, but it is in a passage about black, white physiological differences. And though obviously Thomas Jefferson obviously wasn’t a physician, he was so influential, that when people were reading this, they’re like oh, here’s this thing about black people having inferior lungs. And so doctors in the south and scientists in the south picked up on this myth in order to justify the enslavement of people. And so it’s really — if you look at that history, it is very strange and actually upsetting.

ISAACSON: How do you assess Jefferson when you look at all of this?

VILLAROSA: So I have very mixed feelings about Thomas Jefferson because I’m reading the way he harshly described black, white differences, and really black inferiority. And he talked about how black people smell different, how should be treated like children, have inferior lungs. At the same time, he had a black family, he had family members that were African-American, of African descent. And so I think it is hard to assess him, although there are so many wonderful things about Thomas Jefferson, his writing, his conceptualizing of the constitution. It is hard to vibe it also with the idea that he mortgaged human beings to build his estate.

ISAACSON: I ask about it because in some ways that’s the broader context of this project which is how do we assess not just pointing blame, not just being accusatory, but how do we assess American history with slavery as a central theme?

VILLAROSA: I think it is hard to read some of the stuff that happened to our ancestors. I found it hard. Some of us that were writers on it were crying around some of the stuff we learned. And it is hard to think that this happened to our ancestors, and then people say about my own work that oh, why do you talk so much about race. What — slavery is over. I wasn’t involved in that. And I think this piece while not casting blame on individuals now asks you to think about slavery as foundational in our country and not forget it, and in fact learn about it so teach children about it, teach this in a fuller way than it has been taught in the past.

ISAACSON: When you say it’s foundational, explain what you mean by that.

VILLAROSA: So if you look at — I mean I looked at medicine but you also look at wealth. So even in today’s world, there are people who say they look at black communities and they say oh, look, your communities are so terrible, they’re so dirty, there’s rats, there’s crime. And it is sort of like well, A, that’s not largely true, but B, if black communities are suffering, go back, all the way back and see oh, when slavery ended, there was mass discrimination, obviously forced labor with enslaved people, and then it didn’t just end. These laws continued, laws continued red lining all of these issues. So it is no wonder that, you know, some black communities are in hard times.

ISAACSON: One of the most painful parts for me being from the State of Louisiana was the sugar part, and how the prevention of African-Americans who had been freed from becoming land owners in the sugar industry, which could have been a wealth building thing.

VILLAROSA: I think that that piece is really important and interesting because it reframes a bit sugar. Because we think of cotton as king, but really sugar is queen. And so the sugar industry made so many millionaires out of, especially in Louisiana, and then black people were denied the rights to gain from it. And even currently, there aren’t a lot of black people who are I guess business owners in the sugar area where they’re really successful. At the same time, sugar was really harsh, so the enslaved people were working hard under extremely dangerous conditions. Children were working in sugar factories. And so again, that was part of industry at the time, so if oil made the 1900s rich, then sugar and cotton made the 1800s rich. Yet black people largely aren’t beneficiaries of it now and it is also harmful to us because sugar has a huge impact on our health.

ISAACSON: Yes, that was something that was a great resonance to me, that you talk about the slavery and sugar plantations. And now even the sugar industry in some ways is disproportionate in its effect on African-American health.

VILLAROSA: And its negative effects on African-American health. That’s what I like about this package, that it puts thing together that you don’t necessarily think of. So you’re thinking of sugar, wealth building, slavery, and then it goes back to also health. And so I like that the pieces fit together.

ISAACSON: One of the themes of this project is the lingering impact of slavery, and you said we probably don’t think about on an hour by hour basis in our day. Give me an example of that in health.

VILLAROSA: I think the one that strikes me most is in pain management. And so back in slave times, there were doctors who believed that blacks had a super power against pain, so extremely high pain tolerance. So that has lingered in current medical practice so that a 2016 study of doctors and residents found that residents and doctors when asked about different kinds of pain. So if you get your hand slammed in a door or if you break your ankle, then what is the level of pain? And they believe that black people had less sensitivity to those kinds of pain than white people. And so that effects the way people are treated and their pain is managed. It also makes black people feel we have to be really strong against pain, we do have this super power. So it makes you minimize your own pain sometimes if you’re an African- American because you’re supposed to be strong, that’s the myth. Or it makes you avoid the health care system because you know it is going to hurt because you’re not going to get proper pain management. So that’s one that comes from those days when a high tolerance of pain was a myth that was in society and in the air in order to justify beating people and working them extremely hard.

ISAACSON: One of the pieces that struck me about how we today still have the reverberations from things that were from a long time ago is traffic in the City of Atlanta. Explain that to me.

VILLAROSA: I really like that piece. It was very interesting because the highways in Atlanta were made so that they could purposely get rid of African-American communities. And so they were put through the communities so that they could get rid of them, and also often to hem in black communities and avoid them. So the highways that are present today, that are causing a lot of traffic, came from the segregationist idea that communities should be either removed, black communities, or separate. And so people on Twitter and in conversation are saying that’s why my traffic is so bad because traffic is horrific often in Atlanta. And so if that is a remnant of segregation, then we need to look at other ways that slavery, segregation and these kinds of discussions affected our current system.

ISAACSON: One of the things this series does is reimagine American history. But to me, it also reimagines what journalism could be. Was this a conscious effort to sort of say let’s expand the bounds of what a journalistic project is?

VILLAROSA: I think that is exactly right. And it is part of — what I’m most proud of, I am also extremely proud that so many of us are black journalists because sometimes our contributions don’t get as celebrated as they should. And so it’s really wonderful to have so many black journalists contributing to this to allow us also to delve into some of the issues that we really care about. For me, it allowed me to sort of prove the things I have been saying in my other articles that are about issues, public health, and present day, and to go back and trace them. This project was a way to say no, we really care about this issue, we want to make it high quality and really look back and prove everything. Because I get a lot of push back when I am writing about race so I have to prove every single thing. I have two fact checkers that work with me on all my stories. So to put rigorous journalism behind the history is really important.

ISAACSON: Dean Bakay, the African-American editor of the “New York Times” had a town hall meeting which he was talking about Trump, but he was also talking about race and he said we have to refocus a bit and do things like this. But people say “OK, the “New York Times” is doing this as a way to pivot away from the Mueller investigation and to attack Trump as racist. That seemed weird since this has obviously been in the works a year or so. But explain that sort of criticism and how you rebut that.

VILLAROSA: I think it is hard to talk about race because when you talk about race, people immediately think you’re calling them racist. And so even looking back, tracing, getting all journalists, artists to discuss this in a very robust, rigorous, journalistic way, makes people defensive. And so this is a way to say for me in my work I don’t assign blame, I write about medicine. I’m not saying doctors, you’re all very racist. I’m saying the system is unequal, and it needs to be changed. And so I think that’s what this project is saying too, is to say the first step is admitting that many of the current day structures are based on this 400-year legacy, and 250 years of slavery, and another 100 years of government mandated segregation. And so it is asking and really using rigorous journalistic practices in delving into history to say this is how to think of our country now, and to acknowledge the contributions of insulated people and to really say the legacy remains. So I think that’s what we want to do.

ISAACSON: There are very few white writers or artists involved in this project. In fact, almost none. How conscious was that, and did you debate that?

VILLAROSA: I think it was not intentional to exclude white writers, but it was intentional to hold up, lift up the work of black writers to show that the sort of energy, the importance of black journalists, and artists and photographers. So that was very intentional. I don’t know how much, if it received any push back. I just know that it was really wonderful to see in the contributor’s page, we were calling it the blackest contributors page ever in the “New York Time’s” Magazine because our pictures were there, which was important to show who we are and that we exist.

ISAACSON: You say it wasn’t supposed to be accusatory. In other words, you don’t want people to feel defensive, but you do want people to feel uncomfortable, right? Because it’s a pretty — it causes discomfort reading this series.

VILLAROSA: I think the discomfort is in the honesty and in the pain that our country was built on. And so if you didn’t show that, you don’t understand the full scope. I found it hard. I found it upsetting. But on the other hand, I would rather have the reality and show it so that people understand that this — our country didn’t just become this way by magic. This was built on the backs of human beings.

ISAACSON: In this period where there’s been a resurgence of toxic racism and permission for people to say racist things, how is this series, how is this project going to serve as an antidote to that?

VILLAROSA: I think one of the ways it does is it get people on the other side of this some ammunition to fight back with, and to use facts and to use history to really push back against some of the ideas that are being discussed. And what Nicole Hanna Jones says in her opening essay is that black people have intense belief in our democracy, that we believe in the structures of the United States, despite being the victims of it. And so I really like that idea that we’re the ones who believe in sort of the social safety nets. We believe in letting refugees in, more than other people, because we have been in this country for so long, longer than many other people, and that we have rebuilt the structures of our current democracy.

ISAACSON: Linda, thank you very much.

VILLAROSA: Thank you.

ISAACSON: Good to have you.

About This Episode EXPAND

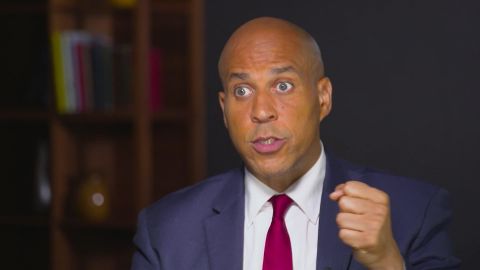

Democratic presidential candidate Cory Booker sits down with Christiane Amanpour to explain his plan to address the climate crisis. Alistair Burt joins the program to discuss Brexit chaos, followed by Yascha Mounk, who reflects on democracy and European unity going forward. Linda Villarosa breaks down her article for the New York Times Magazine’s 1619 Project with Walter Isaacson.

LEARN MORE