Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And we go back to the real world, although you might not believe it, because our final guest this evening has had a life and success worthy of any fictional novel. The San Francisco Mayor London Breed has overcome poverty and tragedy to build a political career that has gone from strength to strength. And like many big city mayors, she’s struggling with challenges like rising homelessness and she’s even gone toe to toe with President Trump over the issue. She told our Michel Martin all about this latest struggle.

MICHEL MARTIN: Madam Mayor, thank you so much for joining us.

MAYOR LONDON BREED, SAN FRANCISCO: Thanks for having me.

MARTIN: How does it feel to be introduced that way?

BREED: Well, it’s amazing because I grew up in San Francisco, born and raised. And just never thought something like this was possible for someone like me coming from some of the most challenging of circumstances right here in San Francisco. And it really is an incredible honor.

MARTIN: Tell me a bit more about that if you would for people who aren’t familiar with your story. I understand you were raised by your grandmother.

BREED: Yes. Well, my grandmother, she raised me in public housing. And the public housing of that time, it was really the conditions of the buildings were just terrible. The mold, the roaches, really the pipes that didn’t work, the challenges of access to water and a number of other issues, the gun violence, the drug use, the drug selling. All of the things that you could think of, not only was it in my community, there were a lot of challenges in my family with drug use and drug distribution. And just watching that and growing up in that environment, it’s easy to think that this is what life is about. And especially because it existed for so many people that I grew with up.

MARTIN: Well, how did you get the idea that life could be different for you?

BREED: Well, I was lucky to have people throughout my life who invested in me. Even my first job working at this place called the Family School, which helped women over 18 get their GED. Showed up the first day, see-through t-shirt, cutoff jeans and didn’t necessarily of course answer the phone appropriately. And the people at the Family School, they worked with me. They took the time to invest in me and talked about how smart I was and that I could go to college and I got a lot of potential. And when the program was over in the summer, they were like we want you to stay. And so I stayed year around. I got paid to do it. So it kept me out of trouble. I focused on my education and really focused on school and really learned in that environment from people who went to college, from people who were successful, who were trying to give back and do things in the community.

MARTIN: So how did you get the idea for public service? I mean, a lot of times when people grow up without a lot, the first thought on their minds is, OK, how can I get more?

BREED: Well, the thing is, I didn’t want to be poor. So the first thought in my mind was how do I do something in life that doesn’t get me arrested, that doesn’t, you know, put me in a situation where I end up in the streets in some various capacities and, you know, how do I take care of myself? And that was the first thought. But the other thought was why am I by myself? Like when I was at U.C. Davis, undergraduate degree, I was lonely because I was going to school with so many incredible people. All of the parents of the roommates I had, they were all there, day one, moving their kids in. You know, I just got dropped off by one of my friends who happened to have a car and we piled everything up in the car and I got dropped off and paid for the gas. Even when I think about, like, the sheets, like, my grandmother — she made sure I took some clean sheets and helped me get ready but, you know, the dorms they have this extra-long sheet thing and so my sheet fit at the top but didn’t fit at the bottom. I put my pillow up there. I worked it. I basically adjusted. And the good news is, that I was in this environment and it really helped me develop but it also made me realize that I was alone, too. And so many people that I grew up with and people that grew up with maybe similar experiences never make it here. And that’s really pushed me to want to do something different, to want to go back — to finish, of course, and then to want to go back to the community and really help change things for the better. Especially because the number of funerals that I was attending, it just got to a point where people that I loved, you know, it just — I couldn’t even do it anymore. And it was hurtful. It was painful. And I was like how do I stop this from happening?

MARTIN: When you were first starting to think to yourself, this is a path for me, did you have your sights set on being mayor?

BREED: No. I just — I didn’t think that –before I ran for office, I first ran for the Board of Supervisors to represent my community. But before I ran for office, I was like my goodness how am I going to raise the money? How am I going to, you know, I don’t have those kinds of resources. I know people. I’m active in the community. I know what to do to work hard, but how do I make those connections? And so when I first was running for office, because of a program like emerge, which helps train democratic women to run for office and a couple of other things that I started looking into, I said, well, maybe I can do this. But it wasn’t about running for mayor. It was about representing my community and the need to start focusing our attention on the kinds of policies that are going to actually work because of my experiences with the policies that didn’t work.

MARTIN: But ironically, now that you are mayor, it’s almost as if the problems are outrunning you.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean one of the big issues that’s in the public mind now, particularly — I’m sure in San Francisco and elsewhere around the country, is the homelessness crisis.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: How do you understand what is going on here right now with homelessness?

BREED: Yes. I mean it’s so complicated. And it’s not just happening in San Francisco. It’s all over the State of California and it’s a real crisis. And it’s a real crisis because there’s a couple of reasons. Number one, so many people that are living on our streets that we’re trying to help are suffering from substance use disorder, are suffering from mental illness. And if it were as simple as I have a place for you to live, would you work with me to take on the responsibility of living there and not live on the streets? I mean, if it were that simple, we would be at a better place than we are now. And it’s been very challenging.

MARTIN: Yes. But haven’t there always been mentally ill people, people with substance problems? The weather here has always been warm. I mean, it seems like there’s something accelerating here.

BREED: Yes.

MARTIN: I mean according to the San Francisco’s gov.org, homelessness is up 30 percent since 2017. What is happening?

BREED: So I think part of what is happening again are those things and opioids, for example, methamphetamine and those kinds of drugs are just being used, I believe, a lot more than they have in the past. But also I think that the cost of living and the fact that we haven’t produced enough housing, housing affordability is at the core of what I know is a challenge for even middle income families struggling to live in San Francisco. Between 2010 and 2015, the city, we concentrated on jobs, jobs, jobs. We have a 2.6 percent unemployment rate. But during that same time for every eight jobs we created, we created one unit of housing. And then it was like a battle between people who are moving here, people lived here, folks who were being pushed out of communities that they were born and raised in, like my friends and family, and including the public housing that I grew up in. It was 300 units. It was torn down and only 200 units were built. So there were a lot of mistakes that were made around housing and housing production and around affordable housing, in particular. Because if we don’t have the places for people to live, that that they can afford to live in, that’s a big part of why we see even more people living in their vehicles.

MARTIN: So according to PolitiFact, when you factor the cost of living, California is the poorest state in the country. What do you think is the primary driver? I mean is it the fact that because the economy is so robust here, in part, that the cost of housing is being beat up beyond the ability for people to pay? What is it?

BREED: I think a couple of things. As I said, we focused in this city on jobs. We didn’t focus on housing. And then now, even now, trying to get housing built in San Francisco is not just about the money. It’s about the process. There was one 86-unit building that basically affordable housing that was just opened last year. It took 10 years from the time of identifying the property to getting it done to opening, you know, up this particular space for 86 families.

MARTIN: So, you know, President Trump was in San Francisco recently. Actually, for the first time since he took office. He told reporters that San Francisco was “in total violation of environmental rules” because of used needles that he said were ending up in the ocean. And he said his administration was going to issue a notice of environmental violation because of what he described was its homelessness problem. And he said the EPA might have to issue a citation. What do you say to that?

BREED: Well, that’s absolutely false. Just to be clear, the president didn’t even step foot in San Francisco. But the fact is, we have a waste water, sewer water treatment system in San Francisco that has received awards from the EPA because many cities, they don’t necessarily allow for their waste water to be treated the way our system is set up like in San Francisco.

MARTIN: But what is he talking about? Do you know?

BREED: No. I don’t know what he’s talking about. But I do know that here in San Francisco, that doesn’t occur because of the way our system is set up. And in fact, I don’t understand how the EPA would give us an award for having such an incredible system, which is a model for other cities to follow and take it away. Who knows?

MARTIN: He also — well, his HUD secretary, Dr. Ben Carson, he also recently visited San Francisco. He did drop by a housing development and he said that the places that have the most regulation also have the highest prices and the most homelessness. He says therefore it would seem logical to attack those things that seem to be driving the crisis. I mean does he have a point?

BREED: I think that it’s — where is his data? I mean, he’s a doctor. Where is his data to substantiate his claim? Just to basically draw conclusion without having evidence is, I don’t think, very responsible. But the fact is, we know that there are challenges with affordability in San Francisco and that’s not a new problem. And so the question is what are they going to do about it?

MARTIN: What are they going to do about it though is the federal government in charge of the regulatory framework for San Francisco?

BREED: I think that they — there are some regulations that — I mean, for example, neighborhood preference and this was a way to provide opportunities for people to have the right of first refusal in their communities. HUD has the say over whether or not we can use that particular system for affordable housing. They can decide whether or not they’re willing to fund or continue to fund a Section 8 voucher or other systems in here which sometimes can make it more difficult for us to either move forward with redeveloping a project or in any capacity.

MARTIN: Well, to that end, though, he also said that the city should be able to sit down with the state and sit down with the federal government as opposed to saying this is what we need, this is what we need. If you don’t give it to us, you’re bad people.

BREED: Yes. I don’t believe that we said if they don’t give it to us that they’re bad people. It’s really we can tell you what we need and this is how we would like to work together and the goal is to try and really make it possible for people to have access to affordable housing in San Francisco. So there have been local HUD officials that have worked with us on projects. And I bring up Sunnydale because that was the most recent example where they worked with us because we couldn’t — we would not be able to rebuild Sunnydale even with private investments, which we need a significant number of private investments without the approval of HUD. So they still play a role.

MARTIN: Do you feel, though, that in a way that you’re between a rock and hard place here? And here I am going to point out your identity as the first African-American woman mayor of the city, in a city in which the black population is declining rapidly. I’m wondering do you feel in a way that you’re kind of caught here as a person who has such important symbolic importance to people because of — not just because of who you are but because of what you’ve been through. And yet the solutions have such a long tail that maybe those solutions will take longer than you have time for. Is that possible?

BREED: It’s possible that some of the things I put into play now will take years. And I will say that I’m really proud, of course, to be the first African-American woman to serve as mayor of San Francisco. But I’m even more proud that since I’ve been in office, we’ve been able to help over 2,000 people exit homelessness. We’ve been able to get people housed and build more properties and master lease buildings that we’ve been able to transition people out of shelter beds into permanent supportive housing. You know, I’m not going to sit back and think it’s impossible. I think anything is possible. If I can, again, come out of the most challenging of circumstances and be mayor, then our city, under some of the most challenging conditions we’re dealing with, we can emerge stronger from it. But it does require good decisions. It does require changes to existing policy. The good investments that will help get us there, it’s going to take some time.

MARTIN: So what is it like for you as you drive around the places you grew up and you don’t see people who look like you anymore?

BREED: It’s tough because even though we had our challenges with our communities and, sadly, we’ve had really, I mean, the violence and some of the other issues that have existed but there’s still love. There’s still love for your community. And when I’m out and about and I see folks, it feels good. It feels good because I do still see people who are still here. There are a lot of folks who are still here but there’s a lot, lot, lot of folks who aren’t here anymore. And it just definitely feels different.

MARTIN: What is the vision, though, for how this is to be addressed? As you know, there are a lot of, you know, different philosophical opinions about this. I mean even the term itself gentrification is a political term, in a way.

BREED: I mean a couple of years back when I was on the Board, we passed neighborhood preference legislation. So that when we build affordable housing in a community, 40 percent of those unit goes to the people who lived there first. And that had been a challenge because, you know, where I grew up, when something gets built, the people who live there and us kids who were adults now who wanted to stay in the communities we grew up in didn’t have access to the affordable housing. We would have to compete in a lottery with thousands of other people and then it completely changed the community. So that’s part of what I’ve done to try and really, at least — I can’t turn back the clock but what we can do is focus on taking care of the communities who are here now and making sure that they are not continuing to be neglected in certain areas of our city. Taking the resources like I was just, you know, in Sunnydale, they’ve been promised and promised and promised. Today, groundbreaking on some of the new housing development and we’re not going to do what they did when I was removed from public housing. Tear down the units, move everyone to another city, and then build less units and know they can’t let everyone come back. It’s like no, you’re staying here. This building is built. You have the option. It’s your priority. One for one replacement and that’s exactly what I’ve been doing based on my own personal experiences of what I’ve seen that hasn’t worked.

MARTIN: But is it the key to your success here? Do you think it’s your own story that makes people feel that they can have hope again? Or is it the concrete investments that actually get delivered that make the difference?

BREED: I got to tell you that I’m probably one of the most progressive mayors that the city has ever seen with the number of investments and policies and things that I’ve put forward in my administration that people didn’t think were possible. Eliminating fines and fees for those who committed, unfortunately, a crime, did their time, and tried to reenter society so that they don’t have the burden of debt.

MARTIN: And you know this from personal — not to put all your business in the street but you know this from personal experience because you had a family member who’s incarcerated for some time.

BREED: Yes. Yes. And the fact is, this stuff around criminal justice reform, the stuff around housing, and affordability and really making a connection between the people who we know need it and access to it, all of those things and how we’ve been able to move things forward has been really incredible. And I got to say, I’m proud of my track record. And maybe if it had been somebody else pushing forward some of these ideas, you know, in some crowds, they may be celebrated more. But San Francisco is a challenging dynamic. People appreciate it but then they want more. And I understand that because I want more. I’m a native. I want to change the city and I want people to be a part of the solution of helping to change the city and make it better. And I do think that part of my story inspires people, you know, to basically know that they can do better in life if they’re in a challenging situation or others who feel like, you know, maybe this is the right solution if it’s something different than what I’m used to even though I might be uncomfortable with it.

MARTIN: Alright. Madam Mayor, thank you so much for talking to us.

BREED: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

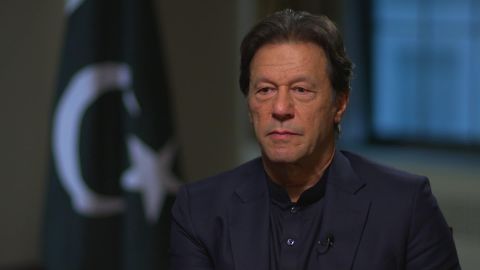

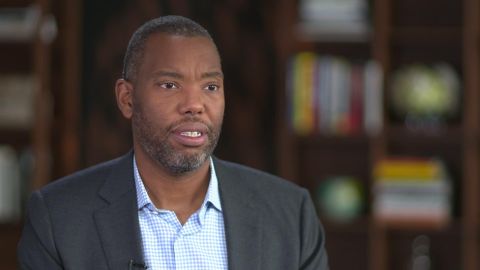

Imran Khan joins Christiane Amanpour to discuss rising tensions between India and Pakistan and his efforts to move Kashmir to the top of the world agenda. Ta-Nehisi Coates explains the vision behind his first novel “The Water Dancer.” London Breed tells Michel Martin about the challenges she’s tackling as mayor of San Francisco.

LEARN MORE