Read Transcript EXPAND

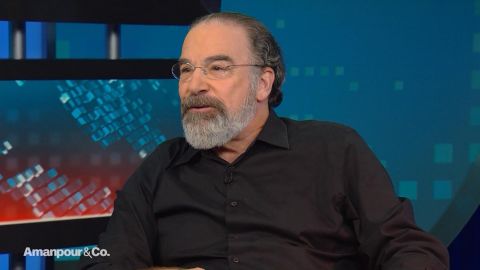

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: The singer and the actor, Mandy Patinkin, has played many roles from Che Guevara in “Evita” to a CIA operative in “Homeland.” But for him, his latest role is his most important, being a real-life advocate for refugees, working with the International Rescue Committee. Patinkin has crisscrossed the globe meeting some of the world’s most vulnerable critical people and it’s had a profound impact upon him and his work as he is told our Alicia Menendez.

ALICIA MENENDEZSo, I think most people know your work on stage and on screen but the work I get the sense you’re most proud of is your work raising awareness about the state of refugees across the world through the IRC. I wonder how did you get started with that work?

MANDY PATINKIN, ACTOR AND SINGER: Well, it was a gift in this point of my life that I wasn’t expecting to receive. I was in Berlin shooting the fifth season of “Homeland.” The first episode of that season to place in a Syrian refugee camp at the exact same time that 125,000 refugees were trying to get across the Balkan route to sanctuary. And at that moment, when I saw those photos and people I saw my own ancestors, my Grandpa Max (ph) and Grandma Celia (ph) my wife’s Grandma Masha (ph) and I felt they were my family. They were little boys and families just like my two sons that are no longer little boys and I wanted to be them and I wanted to hold their hand and give them water and give them comfort and let them know people cared. And I go every year after I finish shooting something to a hot spot somewhere in the world where there’s a crisis, a refugee crisis. On occasion I bring members of my family and we meet people and we record their stories and take photos because of the Instagram world and write — and spend great deal of time describing where we were and what we saw.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: As South Sudanese who has experienced serious effects of war, we discourage conflict.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

PATINKIN: In march of 2016, the wall shut down and European union stopped accepting people, so everything went into limbo. And in terms of temporary crisis where they were moving 5,000 to 8,000 people, you know, at a time across Lesvos, it’s locked. And what became a temporary situation a permanent situation with health care and education and everything. And now, you have — on Lesvos, you have the Moira settlement camp, which is just overflowing. I think 20,000 people on the Greek islands and they have capacity for 7,000. So, people are trying to commit suicide.

MENENDEZ: It sounds like numbers until you see it.

PATINKIN: Yes. And it isn’t numbers when you see it, it’s people’s lives, beautiful people. When we — when I first met, I met the Alassy family, they were the only one left in Kara Tepe in Lesbos. Everyone else had moved out. The IRC had built a city literally with gender-based violence, tents, you know, to take care of women who’ve experienced gender-based violence of women’s issues, of children’s family, tents, showers, medical tents, et cetera. To move 5, 8000 people a day that were coming across in these dinging’s that had room for 24 and 60 people were in them. At one point, I got my wish and dinging came up to the island. Again, somebody handed me a little girl in a pink jacket and that’s all I wanted was to help a child. And then I looked at her and I thought she had died. She wasn’t breathing. I later found out that she had epilepsy, had an attack on the boat. We got her with the IRC to get medical attention and reunited with her family and all is well for that family. But another family I met, they were left with their two boys, the Alassy family in a tent all alone. And I was fortunate enough I was able to give them the means to get to the ferry, to get to — and to get to Germany. And the second year, I took my wife to Germany to reunite us all with that family which was unbelievably moving.

MENENDEZ: When you hear about refugees and the stories we tell about refugees, it’s very othering. And when you actually are with refugees, in that moment you realize, “Oh, wow. This could be me. This could be anybody.” Absolutely. One day, my grandfather used to say in Yiddish, “Dos redele dreyt zikh” which means the wheel is always turning. If you’re on top, you better be nice because one day that wheel will turn and you’ll be at the bottom. If you don’t open that door and be a welcoming human being to your fellow human being, don’t expect someone to welcome you. We’ve become a nation of walls, not welcome. And it’s a humanitarian crisis. It’s a crime against humanity.

MENENDEZ: I wanted to ask you about that because I think very often we talk about the refugee crisis. We talk about it as something that is happening overseas and abroad. When it is happening at our southern border, how does that comport with the work you do with IRC?

PATINKIN: Well, they are there and they are working. It’s a crisis of monumental concern. Some of these families will never be reunited. We’ve lost them. There are some that are already lost just like the thousands that have been lost in the Aegean Sea. You know we’ve lost them but we haven’t lost today and tomorrow. Where is our moral ethical nature, our humanity? It was one of the defining factors of this country, of why we’re here. Our country used to take in approximately 90,000 refugees a year. The previous administration had a cap when they left at 110,000. The new administration came and dropped at the 45,000. But Congress is voting to create a new cap of only 30,000 refugees to the United States America, less than one percent of the world communities welcoming of these people. We are less than one percent the most powerful country in the world and third world countries are taking the brunt of this whole thing. Economically, a humanitarian crisis wise and that’s not proper. And it’s not who we are. Who are you morally and ethically? Take a walk. Be quiet. Be by yourself. Don’t listen to television, newscasts, and podcasts and just ask yourself in private, what is my moral ethical nature and are my representatives mirroring my moral ethical nature? And if they’re not, find representatives who are going into the political field that do represent that. And if you don’t know them, find people who do. And I tell people, I’d much rather you not listen to my music, you not go to my concerts, you not watch my television shows or films, just vote. That’s all I ask is that we vote in this free democracy. Vote. Vote not for yourself. Vote for those who don’t have a vote, those who don’t have a home to belong in. Vote for what you hope never happens to your children or grandchildren.

MENENDEZ: I was brought to mind a quote from David Jones that says, “It is both a blessing and a curse to feel everything so very deeply.” And so the blessing is apparent. There is the passion of the blessing. What’s the curse?

PATINKIN: The curse is it’s good for the work because the work often is a heightened I’m an actor. And so it’s a heightened condition of the human condition that we display often. Even if it’s funny or lighthearted, it’s heightened. And it’s not great in life to have that heightened condition. In life, it’s good to breathe, to be calm. It’s just the name of the game whether you’re the greatest artist or [14:35:00] politician or writer or scientist or school teacher or garbage man, you know, you have two sides of yourselves. Other cultures call it a yin and a yang. You don’t – you need them both. You need —

MENENDEZ: Well, because amidst all of the intensity around your work with refugees and the intensity that you have to bring to that portrayal of Saul on Homeland, your music, you have this recording out and you’re going to be doing live performances. Listening to that music, I was like this is an incredible counterweight to all of this intensity. It is delicate and I wonder sitting here with you if you almost need that.

PATINKIN: I have to have it. It’s my broccoli. It’s my oxygen. I had — I walked away from it for a few years while I was shooting Homeland, not because of the schedule. Because I didn’t — well, I was shooting Homeland before I did concerts but my piano player retired. I’ve been with him 30 years and he wanted to move on. So it’s like Fred and Ginger, you know. I thought I’ve lost my dance partner and I didn’t know if I could go on. And then finally, Bob Hurwitz who’s the president of Nonesuch Records hooked me up with an extraordinary young musician named Thomas Bartlett. And he sent me on Christmas Eve when I was supposed to go do work with the — in Bangladesh with the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar but IRC wasn’t there yet and we couldn’t go for political reasons at that time. So I had 2 weeks in the middle of Homeland to stay home and I called Thomas Bartlett. I said, listen, I got two weeks. You got any time? He said, “Yeah”. I said I just don’t want to do anything that was anything like I did for the past 30 years. I had learner’s block for a few years. He said, “No worries. I’ll send you something.” He sends me 350 songs so I chose 28 of them. I then went into the studio on the 26th of December of ’17 and we started recording. We hit the record button on everything. And then Thomas and I finished, I had to go back to Homeland. And he sent me like, you know, 10 or 12 of these songs and he said, “I think you should listen to this. I think we’ve got something here.”

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PATINKIN: Sing a song of long ago when trees could grow and days flowed quietly.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

PATINKIN: So I worked with Thomas and he gave me a new life. It’s, you know, it’s how I survived.

MENENDEZ: Let’s talk about Homeland. I am a dedicated viewer but for those who don’t know, how would you describe the show?

PATINKIN: Well, it’s become different things in different seasons. It began as a fictional wonder that took a Marine and flipped their heads around and made him an enemy. And we didn’t understand that and it also made the enemy a human being. And that was a wonderful thing to see. And we couldn’t tell what was going on. It was supposed to only last one season, that storyline. But the chemistry between Damian and Claire was so great that they kept it going. And so finally, it came to an end. And then our writers would reinvent and then it became — it morphed into what I would often refer to as kind of a polaroid of our time. And that frustrated me because I didn’t feel we were a reality show or a new show. I feel that we’re an art form where we need to have a poetic answer to the world we’re living in and existing in around us.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SAUL BERENSON: Just don’t communicate with him under any circumstances.

CARRIE MATHISON: Why the hell not?

BERENSON: Because I’m on to another situation. I don’t want you alerting anybody.

MATHISON: What situation?

BERENSON: Can’t say. A Russian intelligence operation involving active measures against the President of the United States.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

MENENDEZ: The actor who I loved as Saul on Homeland was also the actor who I loved as Inigo Montoya in Princess Bride, was also Che on the soundtrack of Evita that I had grown up listening to. Most actors do not get that opportunity. And I wondered at the time, when you took those roles, did you know how big they were going to be, the impact that they were going to have on culture?

PATINKIN: Never. I just went to work and I did what my teacher Gerald Friedman taught me to do, was he taught me how to define an action. My action right now is to listen to you, to hear you. I know there’s a scene that we have been talking a lot. But when you ask me, when I’m with you, and I understand that people out there are listening and my action to them is to try to connect. That’s my favorite word that James Lapine repeated in Sunday in the Park with George over and over and over again, “Connect, George, connect.” If there are any words I want on my tombstone, it’s “He tried to connect.” And what I want all of us [14:40:00] to do globally is try to connect. If we fail, get up again. And if you go to the grave trying to connect, your children will continue it for you but don’t give up. And then when something becomes successful, it’s just you don’t need to understand it, you don’t need to analyze it. If somebody could analyze it and put it through some algorithm, then everybody would have everything they ever did being successful on a big hit. It’s not how it works. It’s taking chances. And if you’re not going to get up in the morning and take a chance and risk something about your comfort zone, don’t get up, stay in bed.

MENENDEZ: Mandy, thank you so much.

PATINKIN: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

Christiane Amanpour interviews Reverend William Barber, author Stefan Kornelius and singer/songwriter Rosanne Cash. Alicia Menendez interviews actor and singer Mandy Patinkin.

LEARN MORE