Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Our next guest wants us all to connect more. Mark Brackett is an emotional scientist, a Yale professor, and he thinks emotional intelligence skills should be taught from an early age. With mental health issues rising exponentially, his work has never been more pressing. And he spoke to our Michel Martin about his new book “Permission to Feel” and how he spent years learning how to do just that.

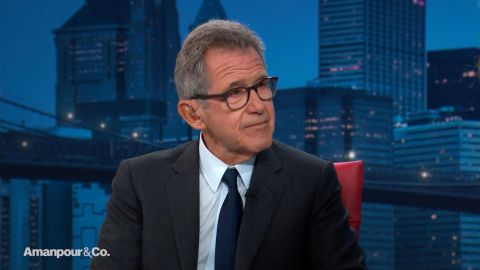

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Marc Brackett, thank you so much for talking with us.

MARC BRACKETT, AUTHOR, PERMISSION TO FEEL: My pleasure.

MARTIN: The thing about this book that I like is that you make it sound so simple but it really isn’t. I guess I’ll start with the title which is “Why do we need permission to feel?”

BRACKETT: You know, permission to feel is an important term for me because, as a child, I didn’t have that permission. I had a tough childhood and nobody asked me to talk about my feelings. Nobody saw what was going on for me, even though it was pretty clear. And so I chose that title because I felt people have to be given that permission. And especially adults who are raising kids and teachers who are teaching kids, we need to create context where children have the permission to experience whole emotions and where they have that permission to express them.

MARTIN: And you talk about it in the book, but do you mind sharing here what is it that lead to that lightbulb moment for you? How did you come to understand how important it is to be given permission to feel?

BRACKETT: Well, as a child, I had an abuse situation. I also was bullied pretty horrifically. And I was very unhappy and I was a poor student in school. And somehow I knew I was smart but I just couldn’t perform well academically. I had two parents who loved me dearly, but my mom was a very anxious woman. So when I would even talk to her about my bullying, she would say, “Oh my goodness, honey, don’t tell me, I’ll have a break down.” And my father was also a great man but he was like, “Son, you’ve got to toughen up.” So I learned very quickly as a kid mom’s going to have a breakdown if I tell her how I’m feeling and dad’s just going to keep on telling me to toughen up. But there was some wizard that came into my life and his name was Uncle Marvin. And —

MARTIN: He really is your uncle?

BRACKETT: He really is my uncle. And he was an interesting character because he was a middle schoolteacher by day and a band leader at a Catskill Mountain Hotel by night. And Uncle Marvin was developing a program to teach kids about feelings through his social studies class. And he was getting a master’s degree when I was in my middle school years. I’ll just never forget, you know, one day he just said, you know, “How are you feeling?” And then he just paused and his facial expression, his body language was so open. And I knew it was a time to just tell him how I felt which was angry, scared, the list goes on. And then he just said, “Well, what can we do about it?” It wasn’t what can you do about it, it was what can we do about it? And that to me, that was the first adult who heard me and the first adult who listened to me and was there with unconditional love and support.

MARTIN: I don’t want to glide past what you said, an abuse situation. I mean, this is a terrible situation. You were abused. I hope this person was brought to justice, at some point, held accountable for his conscious —

BRACKETT: Well, I was the person responsible for that. And you would think that would be something positive, which it was, to some extent. But unfortunately, growing up where I was in New Jersey in the 1980s when this happened, the block turned against our family. Because we had, you know, the pedophile. And it was quite scary for me. Because parents were telling their kids not to play with me. I was on public television, actually, when I was 11 years old talking about this, which just kind of a deja vu moment for me because I think it was inappropriate for me to be on T.V. at 11 disclosing my abuse nationwide.

MARTIN: I’m sorry for that.

BRACKETT: Yes. Well, the ramification, you know, were that stay away from Marc. He’s damaged goods. But now, it’s 39 years later and look what I’m getting to do.

MARTIN: The reason I was thinking about that, though, you know, forgive me, this isn’t when dinosaurs walked the earth. It’s not like people didn’t understand that there was a language of feelings, that feelings matter, that the abuse of a child matters, that a kid should have an opportunity to express themselves. And I’m just curious, like why has it taken so long for people to understand that this matters?

BRACKETT: Because people, in general, see emotions and feelings as weak. Like a man having shame, a man feeling fear, right? You know, it reminds recently when I was giving a presentation, a father who heard me speak about my childhood said I can’t believe how much you talk about your childhood and your bullying. I would never let my son know I was bullied because he would think I was weak. And, you know, it’s eye opening. And what I said to him was, well, what if your son is being bullied? And you’re sending messages to him that say I’m not here to listen to you? What would that mean? How would that make you feel as a dad to your child?

MARTIN: One of the arguments that you make this isn’t just about abuse situations, as you put it. It’s about a skill that you think people need to learn. Can you talk more about that?

BRACKETT: These are life skills. So, you know, yes, I had a traumatic childhood that led me to this path. I also wanted to just say that I feel blessed that I had that uncle. I got involved into martial arts which is a big part of my life. I made it in psychology. I went through therapy. I spent a lot of time giving myself permission to feel. But putting that aside for a moment, you know, just from life is saturated with emotion. The moment we wake up, you know, we think about our workplace and we say do I want to go to work today? Do I not want to go to work today? The commute. Meeting, one meeting, two meeting, three. Life is just filled with emotion. And what we know from our research is that emotions drive five really big things. Our intention. So how we feel, drive for our brains, pay attention. The second is decision making. Think about that. How you feel influences your choices and your judgments from what you eat to, what you buy, to how nice you are or not nice you are to somebody. The third is the quality of our relationships. You know, how you feel, right. If you’re feeling down and depressed, you’re probably not going to approach the world. But when you’re feeling inspired and connected, you’re going to want to move forward. The fourth is mental health and physical health. And, finally, something that I think everyone should care about, which is performance in school and working and creativity. So emotions are responsible behind almost everything we do in life.

MARTIN: I would make an argument that all those things are things that everybody should care about like relationships and social interactions and things of that sort.

BRACKETT: Exactly, yes. And people don’t lose their jobs because of their abilities in the cognitive area usually. But it’s because of their inability to regulate, right. Think about your life in terms of the people who you like to work with and didn’t like to work with. Oftentimes, it’s the people who just don’t have the skills to manage their feelings.

MARTIN: So where do you want us to start in thinking about this?

BRACKETT: Wow. I want us to start, I mean, maybe in utero. I’m serious, though. How moms and dads experience the world affects, you know, the fetus. But truthfully, you know, my work is in schools and in workplaces. So I believe that everyone deserves an emotion education. It needs to be part of the way we think about education from preschool to high school to college to becoming a lawyer, doctor, teacher, whatever your profession is.

MARTIN: So you’re saying everybody deserves an emotion education.

BRACKETT: That’s correct.

MARTIN: OK. That’s carried into this idea of emotional intelligence.

BRACKETT: Right.

MARTIN: Could you just talk about what that is? I mean, this is a term that I think a lot of people have heard for quite some time.

BRACKETT: In fact.

MARTIN: But what is it exactly?

BRACKETT: We say emotional intelligence as a set of skills that help us to use our emotions wisely. So it starts off with recognizing emotions, right. Am I aware of how I’m feeling? Am I aware of how you’re feeling? And then the question is, do I know where that feeling came from? Is it what I said? Is it what I did? Is it from a memory? What is causing my feelings? The third is, what is the exact feeling? What is the precise word? For example, in the angry category. Am I peeved? Am I angry? Or am I enraged? In the sad family. Am I down? Am I disappointed? Am I hopeless. And in the happy family, am I content, or am I happy, or am I ecstatic? That’s the first set of skills. We call it the RUL of ruler which helps us to make meaning out of our own and other people’s emotional lives. Then we have the E and the R, which is expressing and regulating emotion. It has to do with what we do with our feelings. So do I have the permission to be my authentic true self with you? Can I express my feelings at home, at school, at work? Now, do I know how to express them in a way that gets my needs met? That helps other people? And then finally, I think the big, big one is regulation of emotion. So what are the strategies that I use to prevent unwanted feelings, to reduce the difficult ones or even to create the ones that I don’t want to have in life?

MARTIN: People are very, I think, aware of wanting kids to regulate their emotions. I mean, that’s kind of what school is all about, right, sit still, don’t throw your pencil at this other kid that made you mad and that kind of thing. But I think what I hear you saying is that we’re very aware of wanting kids to regulate their emotions but we don’t tell them how to do it. Why is that?

BRACKETT: Because the adults who are raising and teaching kids haven’t had an adequate emotional education. So, you know, think about that. When we’re, you know, frustrated, calm down, sit down, be still. And that’s not being a great role model, right. You can’t yell at someone to calm down. It doesn’t really make much sense. And I think importantly what we also forget is that emotions are what we like to say, co-regulated. Think about this. In a classroom, in a home, in a workplace, right, how as a manager, as a leader if I walk into my 15th in my center, if I walk into a meeting and be like, all right, we have to write another grant. It’s going to bring, you know, it’s going to change the mood. So emotions are co-regulated, right. We’re in relationships most of our day.

MARTIN: You know one of the things that has gotten a lot of attention in recent years is just how stressed out adolescents are. Kids, too. I mean not just adolescents. Some of the data in 2017 about eight percent of adolescents age 12 to 17, and 25 percent of young adults describe themselves as current users of illicit drugs. The number of incidents of bullying and harassments in the United States in K through 12 schools, this is according to the Anti-Defamation link, doubled each year between 2015 and 2017. Internationally, this is an issue. Apparently depression is the leading cause of disability worldwide. So do you feel that your area of study, emotional intelligence, is also a factor here in some of these issues we’re describing?

BRACKETT: I think it says why we need these skills more than ever. You know, and, you know, we don’t think of emotional intelligence being an individual skill. This is skill that is about, yes, the individual I need to regulate when I’m by myself in the airport and if I’m stressed out and overwhelmed. But I also need these strategies with my partner, with my family, I need them at work. And, you know, the truth is, that communities and organizations have feelings. So if you are a leader of a company — to give you an example, I was at a big financial company here in New York City and one of the top executives, you know, he heard me speak and he’s like, you know, this is kind of interesting but, you know, I don’t need this training. So, what do you mean? He’s like “Look at me, I’m the boss. I can do whatever I want. But maybe I’ll have you train the people who work for me because then they’ll have skills to deal with me.”

MARTIN: How do you respond to that? What he’s saying is true, right. He doesn’t care how he makes other people feel.

BRACKETT: He probably doesn’t. What he doesn’t realize is that the people who work for him are going to have feelings and how they feel is going to drive their decision making, the quality of their work, how much time they spend on social media versus doing their work. So maybe if he spent more time thinking about how people felt, actually the company would do even better than it’s doing.

MARTIN: OK. So maybe extend that a little further. Make the business case for why people should care.

BRACKETT: We did a national study in our center with 15,000 people across the workforce from people who work in farming to people who work in finance. And what we found was that people who work for an emotionally intelligent, as opposed to an emotionally unintelligent supervisor have different lives at work. Just to give you one example, feeling inspiration, which is an important thing, probably to feel at work, there was a 50 percent difference in organizations or for people, I should say, when they work for someone who has high versus low-end emotional intelligence. Creativity was significantly different when you work for someone who has high-end emotional intelligence. Your burn out levels, your stress levels, your intentions to leave your profession. So turnover has a high cost to organizations. And so how you feel is determined by the leadership’s emotional intelligence, and there’s greater turn over intentions, when a leader who is low in emotional intelligence, my hunch is that they should read my book and learn these skills because it’s going to make a difference.

MARTIN: And what about kids? Kids can’t leave the institution by and large unless they really act out. I mean they’re kind of captured, right. So talk about kids. Like why does it matter that kids learn these skills?

BRACKETT: Yes. Wow.

MARTIN: And the people teaching those kids.

BRACKETT: Because, you know, emotions are the drivers of kids’ attention in school. You know, people say things like we only learn what we care about. So if we don’t infuse emotion in the learning process and create the engagement, students are going to get bored. They’re going to get distracted. That’s when bullying happens. That’s when students drift off into disengagement. So I think, also, what you’re getting at is this idea of the climate of a classroom. So we’ve done research on that where we have literally videotaped classrooms and looked at the interactions between teachers and students. And what we find is that classrooms where there are teachers who are more emotionally skilled have students who are better learners, there’s less bullying, there is greater academic achievement.

MARTIN: Can you just give us a couple of tips about how you can start giving yourself permission to feel so you can be a more inspiring leader or teacher or be a more inspired student?

BRACKETT: I think you’re saying it. The first thing that I talk about in my book is just giving yourself that permission, that recognize that emotions matter, that they’re valuable sources of information. Second thing is, as I talk about in the book, is the idea of being an emotion scientist versus an emotion judge. So for example, are you open to the experience of all emotions? Are you open to other people’s feelings? Are you open to learning new strategies to help you be better managed, to help you regulate feelings better? The scientist is open. The judge said says “You know what, this is who I am, get over it.” So we’re trying to get people to be more like scientists than judges. And the third is recognize that this is a lifelong journey, that you’re not going to be perfect. And I think the big one is just practice regulating. Like learn new strategies. Most people — I didn’t know what they were until I was a graduate student. So for example, engaging in more positive sub talk than negative sub talk. Catch yourself. Like wait a minute, I’m like — the other day, for example, I was working out in the morning and I said, Marc, you’re going to be positive. And then I was thinking, oh, my legs are so white. I trashed myself.

MARTIN: Oh, my goodness.

BRACKETT: Yes. And I was like wait a minute, Marc, like here’s — like that’s not helpful. It was like catch yourself when you’re doing the negative talk and say, all right, how can I think about this in a different way? What is a different story that I can tell myself?

MARTIN: Marc Brackett, thank you so much for talking with us.

BRACKETT: My pleasure.

MARTIN: And how do you feel now?

BRACKETT: I feel relieved.

MARTIN: OK. Me too.

About This Episode EXPAND

John Browne sits down with Christiane Amanpour to explain technology’s potential to solve our biggest problems. Angelique Kidjo joins the program to discuss her new album, “Celia.” Marc Brackett tells Michel Martin about the importance of emotional intelligence and his new book, “Permission to Feel.”

LEARN MORE