Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

VOLODYMYR ZELENSKYY, UKRAINIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): Please increase the pressure of sanctions.

(APPLAUSE)

AMANPOUR (voice-over): A powerful plea from key, as Russian artillery keeps pounding civilians. Two million have fled Ukraine so far.

And I talk to Jan Egeland, head of the Norwegian Refugee Council, about coping with this humanitarian crisis.

And on International Women’s Day, we look at war through the eyes of women in Ukraine and Afghanistan.

Also ahead:

LT. COL. ALEXANDER VINDMAN (RET.), FORMER DIRECTOR FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS, NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL: Helicopters, ballistic missiles, those are the

things that we need to help the Ukrainians target.

AMANPOUR: Retired Colonel Alexander Vindman tells Michel Martin what more America must do to help his homeland.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London, where Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy addressed the British

Parliament today, beaming in from Kyiv, in a historic broadcast to the House of Commons, rallying support with a reference to Britain’s own

wartime history.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ZELENSKYY (through translator): We do not want to lose what we have, what is ours, our country, Ukraine, just the same way as you once didn’t want to

lose your country when Nazis started to fight your country, and you had to fight for Britain.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And Ukrainian authorities accuse Russia of targeting children, women and the elderly. The U.N. says nearly 500 have been killed so far,

but the real number is likely to be much higher, as heavy rocket fire pins down civilians in besieged cities like Mariupol, outside Kyiv, and here in

Sumy.

Meanwhile, two million refugees have fled Ukraine. Half of them are children. And they’re pouring across borders like Moldova’s.

And correspondent Ivan Watson brings us their stories.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

IVAN WATSON, CNN SENIOR INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): The fastest growing refugee crisis in Europe since World War II spilling across

the borders of the former Soviet Union, more than 1.7 million Ukrainians leaving everything behind and now relying on the kindness of strangers,

people like this grandmother, who says a Russian striker destroyed her family’s home in Mykolaiv on Friday.

“I never thought the day would come when we would have to run away with these little kids,” she says, holding her 4-month-old granddaughter.

Nearly everyone here left their husbands, fathers and sons behind to defend their homes, mothers with young children now on their own in a foreign

country.

(on camera): Imagine if you had to pack up your children, your pets, your belongings into a single suitcase and flee your home and your country on a

moment’s notice. That is what has happened to all of these people.

(voice-over): Moldova, a small relatively poor former Soviet republic, opened its doors to the refugees, providing free transport, hot meals and

shelter to tens of thousands of Ukrainians.

(on camera): This is one of the consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, hundreds of Ukrainians who have taken shelter in a stadium in

Moldova.

(voice-over): This a temporary stop, a place to pause and process their new reality.

These women tell me they still can’t believe the Russian military would shell and bomb their home city of Kharkiv, a city where almost everyone

speaks Russian. After all, Putin claims he’s protecting Russian speakers from Ukrainian nationalists.

(on camera): They say: “Look. Look at where the Russian-speaking people are. They’re all sleeping here.”

(voice-over): This observation echoed at the border by 65-year-old grandmother Tityana Patricina (ph).

“We watch the Russian TV channels, and they have it all backwards,” she says. “They say the Russians are heroes defending us. Look here how they’re

liberating us. Is this a liberation,” she asks, “if I’m running away with a little baby like this?”

She joins the crowds lining up into waiting vans, one of tens of millions of Ukrainians now facing a very uncertain future.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Ivan Watson in Moldova, while, here in Britain, the government is being criticized for choking off the flow of refugees with onerous red

tape. Out of almost 20,000 applications, just a few 100 visas have been issued so far.

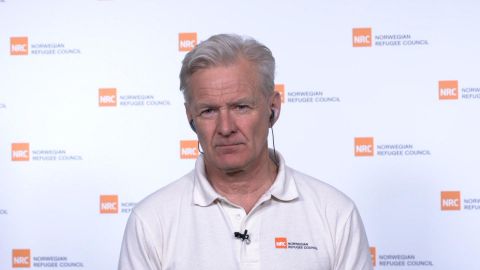

For its part, the Norwegian Refugee Council, an independent group, has announced plans to support 800,000 victims of the conflict both inside and

outside Ukraine.

And Jan Egeland, its secretary-general, is joining me now from Oslo.

Welcome back to the program. We have had you on to talk about Syria, to talk about Afghanistan. And now it’s Ukraine.

How are outside agencies such as yours being able to cope with this very sudden and very rapid outflow of refugees?

JAN EGELAND, SECRETARY-GENERAL, NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL: Well, we’re scrambling resources from all over the world, actually, to scale up a

tremendous aid operation in the neighboring countries, including Moldova, where you just showed images of the needs.

Moldova, a very poor, the poorest country of Europe is now overwhelmed with tens of thousands of refugees. We need to be there. We need to be in Poland

that took — have taken more than a million refugees. And, remember, that’s more than all of Europe took in the refugee crisis year, as it was framed

in 2015, when the whole continent panicked because of one million coming across the Mediterranean.

But our number one priority is, of course, to help all of those staying behind. Two million have left. That means nearly 14 millions are left in

Ukraine, and many of them are in crossfire. We need to come to their relief.

AMANPOUR: So how does that happen? Explain how a humanitarian operation can happen in the middle of an active war.

and in some of these cities where people are talking about being cut off from water and food and electricity and heat and all the rest of it, how

are you able to reach them, Mariupol? I don’t know what’s happening in the east, which is under Russian control anyway.

EGELAND: No, I mean, the honest truth is that, at the moment, our aid workers on the ground — we have 70 Ukrainian staff working since the last

war in 2014 there. They are in bomb shelters. Many have fled themselves for their lives.

So we’re not regrouping in the western part of Ukraine. There, we will start with cash distributions straight to the hands of the mothers and the

fathers so that they have something to purchase needs on the way. There is still possibilities to buy things in Ukraine. And then little by little, we

will resume operations in the east, which is the poorest part of Ukraine, and where people have been living with conflict for eight years.

Many in Europe forgot that there was an active front line in Eastern Ukraine ever since 2014. We were there with the people along that front

line. I was there myself two weeks ago. And I met people who were exhausted before the invasion, elderly people that were freezing under very miserable

conditions.

AMANPOUR: And, of course, you’re talking about the first invasion by Russia, where they took Luhansk and Donetsk in the Donbass region.

But I guess I want to ask you, because, obviously, the Russians on their media and from the Kremlin are portraying a different picture to the

people. They’re saying that they’re providing humanitarian corridors, that they’re enabling cease-fires to let the civilians out.

But it doesn’t seem to be working on the ground. Do you have any evidence that this is happening? And how difficult is it just to get a humanitarian

corridor?

EGELAND: It’s very, very difficult. And it requires some — a minimum of trust between the opposing forces.

The original sin here is to take the war into heavily populated areas. And now cities across Ukraine have war. You cannot have war in populated area

with explosive weapons. It means enormous civilian casualties.

So, a desperate measure in desperate times would be the so-called humanitarian corridors. I was part of the negotiations to organize that

during the long and bitter Syria war. We succeeded in some cases to get convoys in that state. That’s one element of a humanitarian corridor, and

also to evacuate civilians out and into the area called Idlib in the northwest that were — that is still held by nongovernmental forces.

However, there’s nothing sophisticated about humanitarian corridors. It is not a structure or anything. It’s an agreement that there is safe passage

for a few hours along an agreed route. And when not even that has been possible in places like Mariupol in the south, it shows how — the

brutality of this war and the lack of trust among local commanders.

AMANPOUR: And, meantime, again, in neighboring Russia, the people are being told that their forces are not attacking civilians. And yet we see

the pictures.

And you talk about Syria. You were there. It was Russia’s air force that contributed very heavily to the bombardment of cities, to the huge crisis

in civilian deaths, civilian refugees. And we hear the E.U. top diplomats and others in Europe saying they are terrified of the world witnessing and

actually for the Ukrainians, who might undergo the Syrianization of their country.

From what you know, just explain what that will mean.

EGELAND: Well, I mean, it’s so explosive now, Christiane.

Two — it’s not even two weeks, and two million refugees, another two million their way out. If this goes on for months, I cannot imagine how bad

it will be in the middle of Europe. The war could become street by street in large cities like Kyiv, Kharkiv in the north, where I visited.

These are big, big places. So diplomacy must not give up. The war can end, the insanity can end tomorrow. It’s a decision made in the Kremlin. It is

the agreement of the West and Ukraine to talk about the original themes of conflict and to spare the civilian population. Millions are not able to

flee. These are elderly. They are disabled. These are families with children that have no vehicle of transport.

They are encircled, places like Mariupol, where people do not even have water at the moment. This madness can stop. It must stop. There must be new

diplomatic initiatives.

AMANPOUR: And yet the director of the CIA, Bill Burns, testified to Congress. And, as you know, obviously, the United States intelligence was

spot on, and there was the invasion that they warned would be.

And, today, Bill Burns has said that there isn’t any of this that you’re asking — that you’re talking about. There is no perceivable Russian

political endgame, and that now Putin is highly vested in this, and civilians will bear the brunt. Just listen to what he says.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WILLIAM BURNS, CIA DIRECTOR: I think Putin is angry and frustrated right now. He’s likely to double down and try to grind down the Ukrainian

military, with no regard for civilian casualties.

But the challenge that he faces — and this is the biggest question that’s hung over our analysis of his planning for months now, as the director —

as Director Haines said — is, he has no sustainable political endgame in the face of what is going to continue to be fierce resistance from

Ukrainians.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, I mean, you have also been in politics, and you know what it’s like to deal with leaders.

I guess, what is your assessment of what the CIA director said? And he has been an ambassador to Moscow. He’s met with Putin many times. And how do

you envision you and other — U.N., other NGOs dealing with what looks like to be probably an exploding humanitarian crisis of civilian targeting?

EGELAND: Already, it is exploding. Millions are on the run at the moment.

But I refuse to see it as some kind of an inevitable natural disaster that cannot end. I mean, it can end tomorrow by decision in the Kremlin. Talks

in Belarusia could start. Macron could be able to succeed. We cannot give up, because the stakes are just tremendous here.

We could see fighting that is beyond anything in this century. There are 42 million people in Ukraine. It’s a big place. And it’s densely populated in

very many areas. And it’s also a very vulnerable population.

The elderly I saw in the Donbass region in the east — and nobody talks about it because there are no journalists in that part — they are now

engulfed in the fighting for two weeks.

I met this woman. I asked her: “Why aren’t you leaving? I mean, you’re next to the front line. There’s 100,000 soldiers amassing on the other side.”

And she said: “Listen, I’m 71-year-old. My husband is dying from cancer in out hut here. He cleaned up after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster. He got

cancer. I cannot leave him.”

These are the people who are now paying the price for this madness.

AMANPOUR: Yes, madness and war crimes. As we have heard, the ICC is beginning an investigation. I mean, this is really very, very serious.

And, in the meantime, we have talked about the many countries who are taking in nearly two million now, hundreds of thousands in various

countries around…

EGELAND: Yes.

AMANPOUR: … but not here in the U.K.

There has been criticism of the U.K. system, whereby some 300 visas out of some 20,000-plus applications have been processed to date. What would you

say to the British? And we had a very powerful intervention to Parliament today, historic, really, from President Zelenskyy in Kyiv.

EGELAND: Well, what I would say to Britain, as all of the other nations, be part now of a European responsibility-sharing scheme.

Poland cannot take more than a million refugees. I mean, all of Europe said, we couldn’t take a million. Why should Poland be alone on shouldering

that? Moldova, very poor, have tens and tens of thousands now.

So, of course, the U.K. and all of the rest would have to be part of this responsibility-sharing for people leaving, as well as for assisting all of

those left behind in Ukraine, which will cost billions and billions and billions of dollars that cannot be taken from the even poorer people in

Afghanistan and Somalia and in the Sahel and in the Congo.

We’re overstretched and underfunded, with 80 million refugees and internally displaced people before Ukraine happened. All of that, we’re

looking to U.K., we’re looking to all of Europe, and all of the other donor countries.

AMANPOUR: Jan Egeland, thank you so much, indeed, of the Norwegian Refugee Council. Thank you very much.

Russians are also looking for their relatives in Ukraine, but, in this case, the soldiers who Putin and his generals sent into battle.

In recordings shared exclusively with CNN, you can hear the confusion and the desperation in these women’s voices as they contact a Ukrainian hot

line.

Correspondent Alex Marquardt has this report.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): Hello. Is this where one can find out if someone is alive?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): Hello? Do you have any information about my husband?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): I’m calling regarding my brother.

ALEX MARQUARDT, CNN SENIOR NATIONAL SECURITY CORRESPONDENT (voice-over): These are the voices of Russians, parents, wives, siblings, desperately

searching for answers, calling to find information, anything on Russian soldiers they have lost contact with who are fighting in Ukraine who may be

wounded, captured or even killed.

OPERATOR (through translator): When was the last time he contacted you?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): On the 23rd of February, when he crossed the border.

OPERATOR (through translator): Did he tell you where he was going?

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): He said toward Kyiv.

MARQUARDT: This Russian wife, like many others, has turned to an unlikely source for help, the Ukrainians.

In the Ukrainian government building, Christina, which is her alias, is in charge of a hot line called Come Back From Ukraine Alive, which Ukraine’s

Interior Ministry says has gotten over 6,000 calls.

Christina asked that we don’t show her face.

(on camera): Your country is being invaded, but you also feel the need to help these Russian families. Why?

OPERATOR (through translator): We will help find their relatives who were deceived and who, without knowing where and why they are going find

themselves in our country.

And, secondly, we will help to stop the war in general. They don’t know what’s actually going on in Ukraine. So, the second goal of this hot line

is to deliver the truth.

MARQUARDT (voice-over): The Russian relatives who have called this hot line say they haven’t heard from their soldiers since the invasion. The hot

line, which Russian families have found on social media or through word of mouth, gave CNN exclusive recordings of a number of the calls.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): This is not our fault. Please, understand that they were forced.

OPERATOR (through translator): Yes, I understand.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE (through translator): I also want this to end. I want everyone to live in peace.

OPERATOR (through translator): Yes.

MARQUARDT (on camera): What are some of the calls that stick out to you that you will remember the most?

OPERATOR (through translator): A father called.

MARQUARDT: It’s OK.

OPERATOR (through translator): He said: “Our children are being used as cannon fodder. Politicians and VIPs are playing their games, solving their

issues, while our children have to die.”

MARQUARDT: These are the notes from one of the calls. And, in fact this call came from the United States, the relative of a young Russian soldier

trying to find him.

She told the Ukrainians that his parents are no longer alive, that the grandmother in Russia is quite sick. We have his birthday. He’s just 23

years old, and he was last known to be in Crimea right before the invasion. Now, the Ukrainians don’t have any information him. But if they do find him

or get some information, they can then call his aunt back in the United States.

(voice-over): Data from the hot line shows thousands of calls, not just from all across Russia, but also from Europe and the United States.

(on camera): Hello. Is this Marat?

MARAT, RELATIVE OF RUSSIAN SOLDIER: Yes, it is.

MARQUARDT (voice-over): We got through to three relatives in the United States of Russian soldiers believed to be in Ukraine who called the hot

line, including a relative in Virginia of one who also found the soldier’s I.D. and photos on a channel of the social media app Telegram, also

dedicated to finding the whereabouts of Russian soldiers.

MARAT: We do realize that all the signs are pointing to that he is most likely — he was killed in action, but still trying to locate information,

where’s the body that can be potentially found. Maybe, hopefully, he is alive.

MARQUARDT (on camera): Is the Russian Ministry of Defense telling anything to the family.

MARAT: The family is trying to get contacted by anybody, just because everyone is so scared in Russia. Everyone is scared to talk. Everyone is

afraid of law enforcement agencies tracking them.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Alex Marquardt there with that extraordinary and revealing report, while, over at the Kremlin, Vladimir Putin sought to placate

Russian wives and mothers on this International Women’s Day, mindful of the powerful role they play in Russian society.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

VLADIMIR PUTIN, RUSSIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): I would like to address the mothers, wives, sisters, brides, and girlfriends of our

soldiers and officers who are now in battle defending Russia during a special military operation.

I understand how you worry about your loved ones. You can be proud of them, just as the whole country is proud of them and worries about them together

with you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: My guests today know firsthand how women bear the brunt of conflict across the world.

Olesya Khromeychuk lost her brother in the previous Russian invasion of Eastern Ukraine. She’s a historian and director of the Ukrainian Institute

in London. And Orzala Nemat has experienced the Taliban takeover of her native Afghanistan twice now.

Olesya and Orzala, welcome to the program on this International Women’s Day.

And let me ask you first, Olesya, because you know that — obviously, that part of the world is so much better than we do. Putin felt he had to

address the mothers, right, the women whose men have probably not been heard of and have been sent off to a war that they didn’t know was going to

happen.

OLESYA KHROMEYCHUK, UKRAINIAN INSTITUTE LONDON: Yes.

I mean, you want me to comment on what Putin says.

AMANPOUR: Well, I want you to — just the role of women in that society and how he had to address them.

KHROMEYCHUK: International Women’s Day has a long tradition in the post- Soviet space and the former Soviet Union and, of course, in Ukraine and in Russia.

And, in Ukraine, it’s become more and more about women’s rights. And it’s about fight for equality. And, of course, women play a massive role in the

war effort as well here.

So, I — to be honest, I’d rather focus on the Ukrainian women.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: Absolutely, absolutely. We will talk about that in a second.

Let me ask you, Orzala. We’re talking to both of you because both of your countries have gone through and are going through a war on the ground,

against values, for instance, against the human rights of women in your country’s case.

And, this year, they were not able to celebrate Women’s Day as they have done in the past. I mean, they did a little bit. How has it been for women

in your country in the seven months or so since the Taliban took over?

DR. ORZALA NEMAT, SOAS UNIVERSITY OF LONDON: Thank you, Christiane.

Woman in Afghanistan experience an extraordinary situation. There was a time they had handshaking, smiles, full of flowers and beautiful colors,

celebrations of the day, International Day of Women, specifically since 2001.

But I have the same, as a woman from Afghanistan, born in Afghanistan, lived as a refugee for 14 years in Pakistan, we have always celebrated; 8

of March was similar to what my colleague from Ukraine says. It was a big day for us.

Interestingly enough, the conversation since yesterday, not today — I would start with yesterday, quickly, to your audience — was, what should

we do? Like, there is fear, there is confusion about the reactions. We know the reactions of Taliban. And vast majority of those who felt this was part

of the customs, traditions in the Afghan society, they went ahead, and they celebrated, with fear in their hearts.

But they showed. This is a way of showing that we have these values. And, OK, maybe some other people don’t have these values. Then let’s see what

happens.

AMANPOUR: So you’re talking about a kind of resistance, a resistance simply won’t die…

NEMAT: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: … despite the incredible threat and attack it’s coming under.

And in your country right now, it’s the same. It’s kinetic. It’s a war, but the resistance is incredible to watch. Tell me what role women are playing,

because we know that the Kurdish women brigades, for instance, but we haven’t really seen a lot of pictures of women soldiers, but I understand

there are. It’s a big percentage of the army.

KHROMEYCHUK: Absolutely.

Women are playing the role on every possible level of society in this resistance, so standing with the armed forces, and 22 percent or so of the

armed forces are women at the moment.

AMANPOUR: That’s big.

KHROMEYCHUK: Yes, it is so. And the fighting force is about 12 percent women.

So it’s really huge, and more and more are joining the territorial defense as well. And I’d like to highlight that we — we watch these pictures of

territorial defense of civilians taking up arms. And a lot of us admire their effort and their desire to resist in every possible way.

But, really, it’s heartbreaking for me to see civilians having to do that. It means that they feel that they are the only ones who will defend their

own country. They feel on their own, so they’re desperate in their attempts to defend their country.

We also see defiance of unarmed women as well. I mean, I’m sure a lot of your viewers have already seen the images of a woman, unarmed woman,

approaching a soldier, a Russian soldier, and offering him sunflower seeds and saying, put these in your pockets, so that sunflowers, the flower —

for us, the flower of morning and peace will grow out of your body when you die on our soil.

So there’s resistance, powerful resistance, with words, with weapons with everything possible. And the reason for that is because we know what

Russian occupation is like. We have enjoyed it for eight years in Crimea and in Donbass. We have seen concentration camps formed out of captured

galleries.

That was the case in Donetsk. There’s an art center called Isolation, as it happens, Izolyatsia, which has been turned into a concentration camp, where

people chose to commit suicide rather than endure the tortures that they are witnessing. We hear of numerous reports of…

AMANPOUR: Now or then?

KHROMEYCHUK: Well, it’s been — it’s still there. It was captured in 2014. And it’s still in operation now.

And it’s — the situation there is only getting worse and worse. And, of course, who is suffering first and foremost? When we talk about wars, we

usually think of trenches, of battlefields, of the army and so on. But it engulfs the entire society, right? And who is the least protected? It’s

usually women with dependents.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KHROMEYCHUK: We see this in Mariupol. We see this in all of the besieged cities at the moment.

The people who are least protected are women who are looking after the children or the elderly or siblings and others who need protection. At the

moment, they are cut off completely. They have no water. Your reports were covering that very clearly. They have no means of leaving. They are being

fired on as they’re trying to escape.

AMANPOUR: Right.

KHROMEYCHUK: There’s a scorched earth policy happening at the moment.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

And we’re going to get back to also how they’re being separated at the borders, because the men are not allowed to leave.

KHROMEYCHUK: No. No.

AMANPOUR: What was it like for women in Afghanistan during the really bad days of the fighting? What was it like?

What — if I could put it this way, what was their war effort? Because it’s a very different situation. In Ukraine, in the former Soviet Union, women

had a role in the workplace, in society, but not in Afghanistan, except for the last 20 years.

NEMAT: Interestingly enough, the Ukraine experience brings back — although I was a little younger at that time, it brings back the Soviet

invasion time for us, the memories of that.

And listening to your stories, I can be reminded of women in the villages trying to feed or carrying feed. And they — like, one of my own — my

father’s cousins was this young woman who carried food to the mountains. And she was hit from the plane right on the way with the food on her back

trying to bring it to the mountains from the village. So —

AMANPOUR: Taking it to the soldiers for —

NEMAT: To the soldiers.

AMANPOUR: To the soldiers? So that was —

NEMAT: To the soldiers who are fighting the Russians.

AMANPOUR: — part of their war effort. Yes.

NEMAT: This was one role that played. Women in the political prisons, there were political prisoners who are women. In armed action, in what

pictures we see now from Ukraine, probably that was not the case. We didn’t have a lot of women who took guns to fight directly, but resistance comes

in different forms. And it is not always like violence that has to define resistance.

AMANPOUR: Exactly. But you brought up the Russian invasion. And we know that the Russian invasion of Afghanistan lasted 10 years, and it was partly

responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union.

NEMAT: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And you did that. You Afghans did that. When you look at Ukraine today suffering another Russian/Soviet invasion, what would you say to

somebody like Olesya about the — about what it — you know, how this all might turn out?

NEMAT: I have a lot. And I just met Olesya. I am hoping that after this interview, we will have to chat and continue our conversation. There are a

lot of lessons to be learned. And the lessons are for Ukrainian people, definitely lessons to also the super powers trying to compete in putting

the lives of, you know, innocent human beings at the front.

I think the invaders, no matter if they are from the East or West, I will keep it balanced here, should learn big lessons that violation, oppression

and such kind of use of force is taking people nowhere. Anything comes by force will not reach anywhere.

AMANPOUR: And, Olesya, do you take any, I guess, hope from the history whereby a bunch of out gunned resistors in Afghanistan, essentially, they

got weapons from abroad, they got the stinger missiles, antitank missiles and they brought down the mighty Soviet occupation force?

KHROMEYCHUK: Well, I have Ukrainian history to take comfort in. You know, we have been the — a lot of journalists when they phone me up over the

last few days, few weeks really, they ask me a question, what is exactly the difference between Russia and Ukraine? And they don’t understand why

I’m surprised to hear that question, really.

And I say to them, well, why don’t you ask us, how come Ukrainians have managed to preserve their distinct identity for so long in spite of Russian

attempts to destroy that nation for so long, right? So, I know that Ukrainians will resist. I know that we will prevail as well. I know that

Putin’s regime will fall and it will be the best thing for the Russians is when, when it does. The question is at what cost? At what human cost?

AMANPOUR: Well, the human cost we have been seeing on the borders. And again, this is where, you know, the gender roles come in. The women and the

children are being allowed to leave, and the boys, I think, it’s from 17 to 60, 18 to 60 have to stay and fight. Have you thought — I mean, what do

you think about that? Because in your country, women actually fight.

NEMAT: Yes.

AMANPOUR: What sort of effect, morale morale-wise, do you think that has?

KHROMEYCHUK: That women take up arms?

AMANPOUR: Separating them, you know, a lot of women are leaving there.

KHROMEYCHUK: Oh, yes. Of course. But a lot of women are coming back as well. So, what we see at the moment, they — if they don’t have

grandparents who can take their children abroad into safety or at least into the regions. Remember, in war zones, and I’m sure you’ll know this,

people go to the nearest possible place of safety. And that’s usually within the country. And at the moment, we still have regions, my region is

one of them, where people are relatively safe.

AMANPOUR: Lviv is your region?

KHROMEYCHUK: Lviv, exactly.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

KHROMEYCHUK: I come from Lviv. So — and what we see at the moment, that women drop off their children in safety and go back. And they don’t just go

back to fight, they go back to do their jobs. Some are in charge of pharmacies, which are extremely important places now. Hospitals that are

being targeted in the regions that have been mostly affected by the Russian troops at the moment. So, they need to preserve the other hospitals. And

they say, well, we simply have to go back, right?

AMANPOUR: Orzala, I want to read you this from the Taliban spokesperson, Zabihullah Mujahid, who you know of, the Islamic Emirate is committed to

upholding the Sharia rights of all Afghan women. International Women’s Day is a great opportunity for our Afghan women to demand their legitimate

rights. We protect and defend the rights of our Afghan women, God willing. Are you surprised to hear him say that?

NEMAT: Well, to be honest, not really entirely surprised because they are very good in PRs. And everyone in the world should learn from them, the PR

business. Because the gift of the government armed opposition, Taliban including, every years in the last three to four years that comes back to

my mind on the International Woman’s Day was the assassination of vaccinators.

I remember last year, the other — or a year earlier, there was an assassination of journalists and so forth. And this morning, we wake up

with greetings from the foreign ministry, from the spokesperson. OK, good. But the greatest gift of Taliban would have been announcement of opening

secondary high school to the girls. We don’t ask too much, but it’s just very basic. These words don’t mean anything if there is no action.

AMANPOUR: And finally, to you, Olesya. Your brother was killed volunteering to fight the last Russian invasion, right? In the 2014 war.

Tell me what happened.

KHROMEYCHUK: He was a very ordinary extraordinary guy. That’s how I usually describe him. He lived in the West. He actually lived in the

Netherlands for over a decade and then decided to go back to my hometown. He preferred to live in Ukraine. That was in — before the war started.

And then, when the war started, he waited to be drafted. He wasn’t drafted for some reason, even though he had military experience as a conscript from

the 1990s. So, he decided to volunteer. He was watching what was happening in Donbas, much like what we’re watching on a much larger scale now, and he

simply couldn’t — I mean, he felt helpless. So, he decided to join up. And after two years of service, he was skilled.

And when I talked to him not so long before actually, he was killed in Luhansk Oblast, he said to me — I asked him not to go back. So, he was

demobilized. Then I said, look, just be a civilian now. You know, stay in Lviv. And he said, no, I have to go back. And he said, you don’t realize,

this is a European war that just happened to start in Eastern Ukraine.

I didn’t listen to him then. I hear those words every day in my head now. I think what they see from the trenches is a little bit different from what

we see here. Yes.

AMANPOUR: Well, it is incredible that you ended with that because all of our values are being fought for on the battlegrounds of Afghanistan and

Ukraine today. So, Olesya, Orzala, thank you so much for reminding us all on this Women’s Day. Thank you.

And while the West has rushed to arm Ukraine, there are still holes in the country’s defense capabilities. Retired U.S. army lieutenant colonel

Alexander Vindman was the European Affairs director for the National Security Council in the Trump administration, he was also a key witness in

the former president’s impeachment trial. And he is joining Michel Martin to discuss the conflict in his native homeland and how to bolster Ukraine’s

defense.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHEL MARTIN, CONTRIBUTOR: Thanks, Christiane. Lieutenant Colonel Vindman, thank you so much for joining us once again.

LT. COL. ALEXANDER VINDMAN (RET.), FORMER DIRECTOR FOR EUROPEAN AFFAIRS U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL: Thanks for having me on, Michel.

MARTIN: In your latest piece in foreign affairs, you make a case that while Ukraine has certainly fought valiantly against the Russians, they are

going to run out of fuel, ammunition, weapons, aircraft, et cetera. You propose that the U.S. and its allies should implement a land lease program

modeled on one that provided arms and assistance U.S. allies in Europe during World War II. The administration has been very focused on sanctions,

which —

VINDMAN: Yes.

MARTIN: — which you could not handle long-term accountability piece of that. But it’s hard to see what the immediate benefit is to Ukraine

fighting in the trenches as they are seeing people slaughtered. So, what I’m ask you, based in your expertise, both militarily and sort of

politically, what are some steps that could be taken?

MARTIN (voiceover): So, first of all on the sanctions, which is we already made some headway there. There is more head room for additional sanctions.

Some of these — we have to realize that some of these are kind of — they are important, but they are field extensions. There might be a pocketbook

cost to the American public but we have to — remember, that we’re trying to avoid a war and we’re trying to warn off Russian escalation, and there

are things we could do to soften that blow.

We could subsidize some of the oil and gas prices for our public and for the European public to get us there. So, that’s one of the critical things

we could do. This lend lease idea is based off of something we did in World War II, to support the precursor to Russia, the Soviet Union, who is

fighting an existential war against the Nazis. Now, we need to do the same thing for Ukraine. And that’s actually one of the striking things. There is

a messages component to it.

We’re supporting Ukraine against the fascist Russia that’s looking to destroy this large, sovereign independent state, democratic state that’s

striving to join the international democratic union. And the things we needed to do was we need to establish depots. And these are basically

forward positions of logistics to on demand serve Ukraine’s interests.

It is too late for us to wait for Ukrainian to request for supplies and then, ship it in and then figure out how to distribute it. We need it right

there. We need — so, as soon as the Ukrainians want it, they collect it. They move it into the country. That’s basic things like water, fuel, food,

medical supplies for enormous civilian casualties right on the spot. It’s also military supplies, ammunitions, bullets, again, fuel for military

vehicles and some more javelins, these anti-tank systems. It’s more stingers. But it is also more capable systems that really get to the heart

of Russia’s advantages.

And the most important thing is air power. Russia has a massive advantage in terms of air power and long-range fires. These are the ballistic

missiles that have been raining fire down on Ukrainian cities from many, many kilometers away, hundreds of kilometers away, in fact. And what we

could do is we could arm the Ukrainians with these legacy planes from Eastern Europe. That’s — we’re overthinking that one. We’re now bogged

down on how do you get them across the border. You put Ukrainian pilots in and you have them fly across the border. That is not going to trigger a

third World War that we’re giving them planes and letting the Ukrainians fly across the border.

MARTIN: What is the key difference here between what the United States is that they were actually supplying the hardware, even if we’re not operating

it ourselves?

VINDMAN: So, that’s — there is a couple things. First of all, we’re providing — right now, we’ve provided thousands of tactical systems that

have tactical effects. We need operational systems that have operational effects. These are things that are going to really undermine Russia’s

ability to fight this war and to execute a campaign that’s going to really punish cities, destroy cities, kill thousands of people. That’s what we’re

on the cusp of right now.

The Russians are building up forces to conduct these massive assaults. That’s why we’ve seen what amounts to a bit of a slowdown in the last 24 to

36 hours. They’re collecting strength to launch these massive attacks.

So, getting these capabilities in place now could have a meaningful effect on the battlefield. It could strike Russian planes on the airfields in the

next Crimea, in Belarus. On the Russian side of the border, adjacent to the Russian side of the border. Helicopters, ballistic missiles, those are the

things we need to help the Ukrainians target.

And we need to remember, right now, we still have — we’re in this mental block that somehow, we could return to business as usual. Somehow, we could

— you know, there is a scenario where we end this conflict and it stays limited. But that’s not the trajectory we’re headed towards. We’re headed

towards a trajectory of a protracted war that gets increasingly nasty and draws us further in.

The decisions that we think are tough today are going to be easier in the future. We’re going to have much, much more difficult decisions to make in

the future. We just need to look ahead a little bit and not think about just short-term risk, but medium and long-term risks and how this develops

in a very, very violent way that drags us in.

And if we make that switch, then it is easy to provide these capabilities, these systems to the Ukrainians, and they could man them.

MARTIN: What is your sense why the administration and other allies are hesitant? As you’ve said, the big debate has been over the United States

and the allies and NATO enforcing a no-fly zone of Ukraine. There seems to be no political will on either side of the aisle for that in the United

States at least and certainly, not in NATO. But you’re saying that’s not necessary. The Ukrainians could do this.

So, why do you think — what is your read of the situation here?

VINDMAN: Sure. You know, I’m not even sure where to begin because there are so many different features here. But one of them is this defeatist

attitude, that somehow based on these assumptions, looking at tables on a chart and how much force Russia had to bring to bear and what the

Ukrainians had that this would end quickly.

And in that — this kind of mentality, you’re looking to minimize risks because the outcome is inevitable. So, why put resources in and why risk,

you know, a larger confrontation with Russia if it’s inevitable? We’re still not off that, frankly. There is still a defeatist attitude because

people that — in a lot of cases, there just really aren’t that specialists that focus on Russia that look beyond the tables, that understand, you

know, what — the asymmetries and morale that the fact that the Russians — that Ukrainians will not roll over, that the Russians don’t have sufficient

combat power.

There is also a great deal of wishful thinking in a — in the White House below the level of the president that these stays limited, that the — that

there is a way to let this play out between the largest country in the world and the largest country in Europe and nobody else gets involved. That

is an absurd assumption because, already, there is enormous pressure growing on Eastern Europe. They’re bearing the brunt of this with regards

to refugee flows.

They are the ones that are most forward leaning. Certainly, the Baltics, the Pols, the Romanians recognize that this doesn’t end with Ukraine and

they want to do more. They’re — we’re the ones that are holding them back. We’re the ones that actually arrested, from what I hear, the transfer of

these aircraft in the moments that it was conceived because we thought it was too risky. And now, we’re pushing it, but we lost the momentum,

frankly.

We lost the momentum. There was an opportunity to do this. And it’s because we’re risk averse. We still think there is a chance this goes back to

business as usual, you know, where, in fact, in a Cold War, we’re headed towards a hard war.

And these folks, these people that have gotten to know don’t get it. They simply don’t get it. They’re focused on things that matter under almost

every other circumstance like upcoming elections and fuel prices. And what that means, instead of understanding that we’re in a fight for the future

of the 21st century and that this — we’re either going to face an enormously emboldened and more powerful adversary, you know it might be

isolated economically in the form of Russia and authoritarian world or the authoritarianism, they have — or authoritarian world that we have been

concerned about that’s, you know, surging forward is on its heels.

I’ve got to say, this is the most forward leaning I have been in, frankly, in terms of criticism, but we are at a tipping point. So, it is important

to make these points.

The — it’s a very insular administration. These are folks that have been close to President Biden, Vice President Biden for years, and they want to

insulate him against — you know, against the shocks of mismanagement like Afghanistan where these people actually were the ones responsible for, you

know, accelerating plans that didn’t really make sense or executing a withdrawal that should have been more thoroughly planned. And they’re still

there.

And at sometimes, you need to be able to tell the chief, the boss that he’s not wearing any clothes, that his assumptions are invalid, that, in fact,

there are — the risks of escalation are minimal and he doesn’t have people that will do that right now. He has people that are going to — that are

going go — cater to his wishes and are not going to push back at a minimum.

There needs to be a little bit more reflection about the missteps we’ve had over this year with regards to the execution of Afghanistan. Not the policy

decision to leave, but the way it was executed and shepherded by the National Security Council. And then, again, now, with this major war

unfolding, they’re underperforming and I’d like to see more.

This is not a sharp criticism against President Biden because President Biden, frankly, in fact, is a product of 20 years of Ukraine and Russia

policy where we have been looking at this relationship through a soda straw. We’ve bistar our activities towards Russia thinking we can do more

than we can instead of places like Ukraine where we have willing partnerships.

MARTIN: And I also want to ask though what impact do you think the sort of a four years of the former president’s posture toward Russia, what impact

that’s having now? He’s no longer in office, but some of the people who are espousing that view still are. And I’m wondering what influence that

perspective has on the president’s ability to sort of coalesce around more aggressive strategy.

VINDMAN: This is a critical point. Frankly, the logic now that most of the American public just didn’t have the context to understand is the

importance of arming and supporting Ukraine and the president’s corruption and abuse of power in the first impeachment and how that’s directly

connected to today.

There is now — you know, it’s not a leap anymore. It’s the fact that the president undermined that relationship. That’s clear. But there is a deeper

point here. I was saying that we were headed towards this confrontation with Russia sooner or later based on Russia’s provocative actions, they

were eventually going to cross the red line.

So, if we were creeping from Bush — George W. Bush through President Obama, through — we were creeping towards that confrontation, we lurched

forward during the Trump administration. Because in that administration, we had a couple of foundational shifts. One of them was the catering to

Russia, the efforts to really kind of elevate Putin as a world leader, as a credible actor, as kind of one of the guys, as a — as somebody that should

be welcomed into the community of nations. That’s what President Trump did.

Trump created some opportunities. He basically indicated that there is a softening of the Republican position. The Republicans have been traditional

hawkish around values issues and around authoritarianism and things of that nature. So, there was a softening there. There was a fracture between us

and our allies, our NATO allies, another opportunity. And the enormous discord that Trump sewed inside the United States was extremely meaningful.

We’re a super power and we looked weak because of Trump.

And not just when he was in office, but even after we left. We have to remember that the insurrection started January 6th. The build-up for this

war started just days later. The timing is telling that Vladimir Putin saw deep opportunities based on President Trump’s insurrection, the fact that

we were hyper polarized and the fact that Trump has captured the Republican Party and the belief that somehow the Republicans were no longer going to

be opponents to Putin’s aggression and belligerence.

And that didn’t just end when Trump left office. He continued that through to literally hours before this war started. So, he was elevating and, you

know, and appealing and appeasing Trump in the hours before this war. What message does that send to Putin? It sends a very simple message, that the

Republicans will not be part of the response to Russia. They will not be part of the cost imposition for Russia, just as President Biden is trying

to signal that there would be a cost. So, the rhetoric from the president is sanctions will be fierce, heavy.

And on the other side, you have Trump saying, we’re your friends. Don’t worry about us. Tucker Carlson is saying this. Mike Pompeo is saying this.

You know, Ron Johnson. These folks are actually undermining the deterrence efforts of the U.S. government to try to avoid the war. So, that’s why I

say that they have blood on their hands because we could have potentially avoided this but they undermined our efforts to avoid this.

And now, we have this major war that threatens U.S. national security whether we see it or not. It is right on the horizon, and they dug a hole.

They’re going to have to lay in that hole, the Republican Party. They’re trying to distance themselves, but it is too little too late.

MARTIN: Before we let you go, Lieutenant Colonel Vindman, I can’t help but think about what this moment is like for you as a person who tried to warn

the country about the dangers that were looming, about the dangers of the region, the lack of support for the Ukrainian president and his efforts in

the democratic movement within Ukraine and, of course, Trump’s appeasement.

You tried to warn the country about this. Certainly, this is not a moment that you take any pleasure in being right, but what is this like for you?

VINDMAN: It’s tough, frankly. You know, I definitely saw the peril on the horizon and tried to do the best I can to warn the administration

internally, the American public, you know, certainly put myself and my family at risk, and we just kept stumbling forward.

And that happened, you know, while I was in government, and that continued to happen even while I was out as I’m still — I still consider myself a

public servant. In the months preceding this, I was — you know, I put my credibility and my legitimacy on the line, being so assertive about the

fact that this is all but certain to happen. And we need to do something to avoid it, and we failed. We didn’t do that. We didn’t do enough.

I mean, now, I’m yelling and screaming about the fact that we are on the cusp of a hot war. We need to do more to avoid this. The longer this goes,

the riskier it gets. The decisions that we have to make weeks and months from now are going to be much, much more dangerous. We need to make some

courageous risk-informed decisions now to avoid that. Otherwise, we will find ourselves in an untenable position.

We need to do that now. We need to provide the Ukrainians the support they need. It is going to get worse. I cannot be more adamant about it. My — I

— my desire to see this administration succeed in light of the risks of reversals in the upcoming elections, I’m setting those aside, because right

now, we have much more — we have an imperative.

We have a war that we could be dragged into. We need to do everything we can to help the Ukrainians to win this or to freeze this, to move this to a

diplomatic solution quickly. Otherwise, we have every risk of ending up in this war, and that’s where really all our — we are all in peril. It is not

the say boar rattling now. It’s the creeping, the incremental ratcheting up of tensions that brings us in, that’s what brings us to risk.

And I’m done being restrained about — not that I — I tend to be plain spoken, but I’m done with that. This is the time to act. You know, I will

deal with the consequences of, you know, burning the bridges with the — on the other side of the aisle, I guess credibility or affinity from. But

that’s where we are and that’s what we need to do.

MARTIN: Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, thank you so much for speaking with us today. I do hope we’ll talk again.

VINDMAN: Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: A really important message there.

And finally, tonight, the world’s largest museum is set to right a historical wrong. The Smithsonian Museum has agreed to return most of its

collection of 38 Benin royal court art works to their homeland in Nigeria. These artworks were looted by the British in a raid on Benin City in 1897.

They were then sold off and scattered around the world.

The Smithsonian deal gives Nigerians’ control over how their art will be displayed. The British Museum, which holds one of the largest collections

of Benin bronzes in the world, remember that raid in 1897, has not returned any.

That is it for now. Thank you for watching, and good-bye from London.