Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY. Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

SIAMAK NAMAZI, PRISONER, EVIN PRISON: The other hostages and I desperately need President Biden to finally hear us out, to finally hear our cry for

help and bring us home.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: A cry for help from an Iranian prison. In an unprecedented conversation, I speak with the detained Iranian American Siamak Namazi from

inside Evin. He’s desperate plea to President Biden.

Plus, analysis with the Former State Department Advisor Vali Nasr.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHAEL R. GORDON, NATIONAL SECURITY CORRESPONDENT, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL: You are dealing with a potential adversary really that has the

homecourt advantage.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Is the United States ready for the era of great power conflict? Walter Isaacson speaks to Michael Gordon, national security correspondent

for “The Wall Street Journal.”

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in New York.

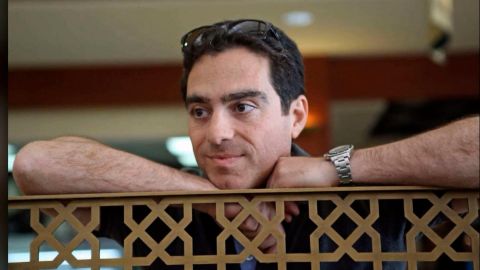

And tonight, we have an extremely difficult, important, and highly compelling conversation in hugely unusual circumstances. Siamak Namazi is

an Iranian American businessman imprisoned in Iran for over seven years. He spoke to me over the phone from inside the notorious Evin Prison, giving us

a firsthand look at the desperation of foreign nationals, dual citizens detained in that country.

I first interviewed Siamak back in the early 2000s during the reform era, a very different Iran then. He was a prominent businessman and an analyst

trying to build relations between Iran and the U.S. Siamak was arrested during a 2015 business trip and convicted of cooperating with a hostile

foreign government, only that government is the United States and he is a U.S. citizen.

It’s a conviction, of course, that he completely refused. In the following years, American detainees have been released as part of prisoner swaps with

the United States. Siamak’s own father who was also arrested in 2016 while trying to visit him in prison was released on medical grounds last October.

But Siamak continues to languish in prison even going on a week-like — a weeklong hunger strike back in January and writing a letter to President

Biden.

Now, he says, he feels so alone, so abandoned, and so out of options that he has decided to come to us, hoping to beseech Biden to help him and the

other Iranian Americans. And here is our extraordinary phone conversation.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Siamak Namazi, it’s a rare, rare thing to hear from somebody inside Evin Prison. Can I start by asking you to stay your name and where

you are actually talking to us from?

SIAMAK NAMAZI, PRISONER, EVIN PRISON: Well, my name is Siamak Namazi, and this call is being made from ward four of Evin Prison in Tehran.

AMANPOUR: Siamak, it’s a long. Long time since we last spoke, when we met in Iran. And I want to say that this is very, very unusual to speak to

someone inside Evin Prison. Why are you speaking to us in this way? Why are you speaking out now?

NAMAZI: Well, Christiane, first, it’s good to hear your voice as well after so many years, directly and not under on a recording that someone’s

playing back to me. I think the very fact that I’ve chosen to take this risk and appear on CNN from Evin Prison, it should just tell you how dire

my situation has become by this point.

I’ve been a hostage for seven and a half years now. That’s six times the duration of the hostage crisis. I keep getting told that I’m going to be

rescued and deals fall apart where I get left abandoned. Honestly, the other hostages and I desperately need President Biden to finally hear us

out, to finally hear our cry for help and bring us home. And I suppose desperate times call for desperate measures.

So, this is a desperate measure. I’m clearly nervous. And just like it’s hard for you, it’s very intimidating for me to do this.

I feel I need to be heard. I don’t know how long I have to wait until the White House understands that we need action and not just to be told that

bringing us out is a priority.

AMANPOUR: Siamak, let me follow up on that because you did write an op-ed that was published in “The New York Times” in the summer —

NAMAZI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: — in which you said that, the Biden administration’s approach to rescuing Americans in distress in Iran has failed spectacularly so far.

And you’ve recently gone on, I believe, a one-week hunger strike to draw attention. Tell me what you mean by failed spectacularly so far.

NAMAZI: I mean, seven and a half years in, I’m still in Evin Prison. Look, I believe that the U.S., with all its power has the superpower in the world

has a great amount of leverage. And I believe that had that leverage been properly used, we would have been out a long time ago.

I think what is clear is the following, that the three of us, Emad, Morad, and I, are hostages in Iran. We have not so much as jaywalked. We’ve been

taken for one reason and one reason only and that’s because we are U.S. citizens. And the flipside of that is we will be only released through a

deal with the U.S. You know, all I could do is repeat that seven and a half years is six times the hostage crisis. What is it going to take?

AMANPOUR: Well, I’m going to try to ask you about that, you know, what is it going to take. But first, you’re one of three Americans in Evin. They

are detained on so-called charges of espionage, but you are not. You are detained and sentenced on other charges. Do you have any awareness —

NAMAZI: Sorry, I need to correct you on that. We all have the same charge. We are all charged under section 508, which is a very nebulous charge of

cooperating with a hostile state, in our case, referring to the United States of America. We — none of us have had access — I’ll just speak for

myself though, but we don’t — we are ordinary citizens. We don’t have access to any classified information to give to anyone. Which is why we

were charged with section 508, cooperating with a hostile state and you’re very free to ask details about that.

AMANPOUR: Yes, I want to know whether you are in the same location as the other Americans, Morad Tahbaz, Emad Shargi.

NAMAZI: Yes, I currently am. We have not always been. All three of us were at the same detention center at different times. Obviously, I was taken two

years and two and a half respectively before Morad and Emad. But today, we’re all in the same place.

AMANPOUR: And do you hope to all be released together?

NAMAZI: Absolutely. I know what it feels like to be left behind. And I wouldn’t wish it upon my worst enemy. We are all in this together and I

hope that this solution is found for all of us together.

AMANPOUR: Siamak, you wrote this letter to President Biden recently. And I’m going to quote a little bit from it, “Day after day, I ignore the

intense pain that I always carry with me and do my best to fight this grave injustice. All I want, sir, is one minute of your day’s time for the next

seven days devoted to thinking about the tribulations of the U.S. hostages in Iran.” Did you get any personal response to that letter, Siamak?

NAMAZI: I’ve never had any response. This is what makes things particularly painful. President Biden has been in office for 25 months now.

You’ve got to excuse me, this is hard.

AMANPOUR: I know it’s hard.

NAMAZI: It’s hard to expose yourself to the world. President Biden has been in office for 25 months. Now and we kept — that the White House

declared that we’re a priority, rescuing priority. In 12 months — that the president hasn’t so much as made a minute of his time available to meet

with our family, if just so much so much as to hear them out and offer them some words of comfort. So no, I have not heard anything. I don’t know what

I actually have to do in order to get some comfort from the Biden administration.

AMANPOUR: Can I ask you about your own physical? You used the word comfort. I want to know how you are being treated, if you can. How is

everyday life for you there? How do you get through the days in Evin?

NAMAZI: Right. Look, there’s only so much I’m comfortable saying on CNN about this.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

NAMAZI: But I think the short answer is that I’ve always been made to feel that my very humanity has been taken away for me, not just my freedom.

Today, I’m in the general award. The situation in the general ward is far better than the corner of hell that I used to be in, in the detention

center. It’s far from a pleasant place to be in, but everything becomes relative.

It’s still extremely difficult to bear the very basic fact that I am denied many of the rights of a prisoner because I’m a hostage. I don’t know how to

convey that. I see hardened criminals, I see members of members of Daesh, I see people who — human traffickers have more rights than I do. And, I

don’t know, you know.

So, yes, our general circumstances and the general ward are OK. And I would say that we do the best that we can to adapt to our circumstances. I

personally take comfort, to use that word again, in the fact that I know that I am doing everything I can to fight this injustice. I want to say

that my situation today is very different than the first 27 months of my arrest when I was still being held at this detention center. There, my

situation was really precarious. I did not feel safe at all.

And I want to mention that the Obama administration knew exactly, exactly how unsafe I was. I made sure of that. At that point, it seemed my captors

had made it their mission to strip me of any semblance of human dignity. I spent months caged. I spent months caged in a solitary cell that was a size

of a closet, sleeping on the floor, being fed like a dog from under the door. And honestly, that was a least of my troubles. I, to this day — I’m

sorry, I didn’t realize this was going to happen.

AMANPOUR: Siamak, you are under extreme duress.

NAMAZI: I’m really sorry, it’s so hard for me. I suppose the positive side is someday, some therapist is going to make a good bit of money out of it.

OK.

AMANPOUR: You are able to make those quips —

NAMAZI: Sorry, please go on.

AMANPOUR: — and there is some positivity to hearing that you are still robust and that you still have your strength. I want to ask you —

NAMAZI: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: — about the other Americans, because what you’ve said is you just don’t understand why you have been left behind, particularly over a

period of years in which other Americans have been released in deals between Iran and the United States.

NAMAZI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: They were released in 2016, around the Iran nuclear deal, including Jason Rezaian, the journalist, then again in 2019 and 2020. Each

time, you were left behind. Do you know why? Do you know why you were not included in that group?

NAMAZI: No, you know, I’ve been in prison all this time and I, obviously, am not in touch with U.S. officials. Now, I have served prison time,

interestingly enough, with some people who were on the other side of the negotiation table during the 2016 hostage deal with the U.S. They also tell

me that the Americans did not push very hard. Why? That’s a question I really would love you to ask Secretary Kerry someday on my behalf.

And I should tell you that it wasn’t just that they left me behind. Obviously, when that happened, I was completely devastated, shattered, and

despondent. You know, as a hostage, you only cling onto one thing, you know. When I’m there in that closet sized room all alone, there was one

thing I held as true, and that is that the U.S. government is fighting to release me. And then you know, one day, I realized everyone’s gone and I’m

left there alone.

So, this is worse than the fear that political prisoners have that they’ll be forgotten.

I was being abandoned by the U.S. government at a time they knew, they knew how dangerous my situation was. I don’t know how to convey that. At the

time, I understood that the Obama administration and left me, but they essentially — they didn’t get me out of danger, but they essentially

handed me an IOU.

Secretary Kerry had promised my family that the U.S. government will have me out within weeks. Obviously, seven and — seven years later now, and

this was the occasion of my — the seventh anniversary was the reason for my hunger strike, to remind them of that promise, that just didn’t happen.

Not only was I not released but, you know, those weeks passed by and one day, all of a sudden, I get called into the interrogation room and I was

cudgeled with a video clip showing my ailing father wearing prisoner’s garb and a blindfold in one of the other interrogation rooms.

So, no, I would love to know what happened. I just know I was abandoned. I know I was promised that the U.S. government will release me weeks later,

and it seems like, you know, three weeks is perpetually — I’m perpetually three weeks away from the freedom that is permanently elusive.

AMANPOUR: It must be so, so, so hard for you. I can’t even imagine. You mentioned your father. Of course, he was arrested.

NAMAZI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And he, as you say, an elderly retired UNICEF official. When he actually came to try to visit you in prison, he was imprisoned for two

years, following that prevented from leaving the country for five years until he was finally released this past October. And you were then given a

furlough, a brief furlough, to see him before he was allowed to leave the country, you were not allowed to leave.

I guess I just want to know how it felt when you were able to see him, that you could see him at least, going to safety and whether you hope and think

you will be reunited.

NAMAZI: If you want to get me balling, talk about my dad. You know, every father — I mean, every father could be his son’s hero. Mine certainly is

mine. My dad is my hero. I mean, how can he not be? He spent his entire life going to far corners of the world, to the poorest, most dangerous

possible places to save children. How could I not completely be enamored with this man?

And when it comes down to it, I — to this day, I carry tremendous guilt that it was my choice to come for a four-day trip to Tehran. And I got

arrested, and as you said, my father got lured back and tricked and arrested because of me. So, there’s this tremendous guilt.

This 79 years old human rights medal-winner of the United Nations tossed into — on the floor in a solitary cell somewhere and interrogate harshly,

and then handed a 10-year prison sentence, which at his age and with his ailments, that was a death sentence which got way too close for it to

happen. I mean, he was — from that detention center, they — you know, he was ambulanced to the hospital several times. He had several heart

surgeries, including getting a pacemaker made — put in. So, he was really in bad shape.

Yes, seeing him finally leave, it’s a huge, huge burden lifted off my very guilty shoulders. Of course, I know who arrested him and I know that it’s

not my fault, that they are cruel people who take, arbitrarily arrest a 79- year-old man and treat him that way. But the fact is he came for me.

But yes, I — you mentioned that I got furlough. By Iranian law, I’m owed something over 100 days by the strictest interpretation.

It’s my right which rate is being denied. But I’m so grateful that for those 10 days I was allowed to go. And I have to acknowledge — and it was

October that Iran showed some long overdue humanity by lifting the illegal travel ban that they’d put on my father. My father was a free man by

Iranian law, with a travel ban that had absolutely no justification whatsoever. But still, they lifted it.

We didn’t know they were doing that. I was given furlough and then they came and told us, and my dad was in disbelief. He thought they’re messing

with him. He thought that it’s one of these games that they play that we’ve seen, but it wasn’t. It was genuine. They allowed him to leave to get — to

join the rest of the — our family and to receive the care that he needed for his life-threatening condition.

For that, I’m deeply and sincerely grateful to those in power in Tehran. And I can only hope that they summon that same spirit of humanity to do

what is needed on their part, so that the rest of us, Morad, Emad, and I, can also be reunited with our families and to start putting this dark past

behind us.

AMANPOUR: Siamak, we will get your message out to the world. And thank you for being so brave as to talk to us at this time.

NAMAZI: I would really appreciate it if I can also — if I could also get a chance to address the president directly.

AMANPOUR: Go ahead.

NAMAZI: Honestly, I really need to be heard. If this — I’m taking this risk for this opportunity. So, I hope you give it to me.

AMANPOUR: Go ahead, Siamak.

NAMAZI: OK. President Biden, I certainly hear and I sincerely appreciate your administration’s repeated declarations about freeing the American

hostages in Iran is its top priority. But I remain deeply worried that the White House just does not appreciate how dire our situation has become.

It’s also very hurtful and upsetting that after 25 months in office, you have not found the time to meet with our family.

Please just give them some words of assurance. Sir, Morad, Emad, and I, have now collectively languished here for 18 years. Our lives and families

have been utterly devastated. We desperately, desperately need you to finally conclude that we’ve suffered long enough as Iran’s hostages.

President Biden, you and you alone have the power to deliver on the Obama administration’s broken promise to my family. I implore you, sir, to put

the lives and liberty of innocent Americans above all the politics involved and to just do what’s necessary to end this nightmare and bring us home.

Thank you.

AMANPOUR: We will get that message out, Siamak.

NAMAZI: OK. I’m sorry —

AMANPOUR: I hope we can talk again.

NAMAZI: I’m sorry. I —

AMANPOUR: Don’t be sorry.

NAMAZI: OK. Thank you for doing this.

AMANPOUR: Thank you for doing this.

NAMAZI: Take care.

AMANPOUR: You take care, Siamak.

NAMAZI: Bye-bye.

AMANPOUR: Bye-bye.

NAMAZI: Bye.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, we defy anybody not be moved by that cry from prison. Of course, we reached out to the White House for comments on this

conversation. And they did give us the following response. They basically said, Iran’s unjust imprisonment and exploitation of U.S. citizens for use

as political leverage is outrageous, inhumane, and contrary to international norms. The United States will always stand up for the rights

of our citizens wrongfully detained overseas including Siamak Namazi. Senior officials from both the White House and the State Department meet

and consult regularly with the Namazi family, and we will continue to do so until this unacceptable detention ends and Siamak is reunited with his

family.

Now, we have also reached out to the Iranian foreign ministry about Siamak and his fellow American detainees, and we’re still waiting their response.

So, let’s dig a little deeper now on their plight with Vali Nasr. Himself, an Iranian American, he is the former senior adviser at the State

Department and he’s now a professor of international affairs at Johns Hopkins University.

Vali Nasr, welcome back to our program today from San Diego. I guess my first question has to be your reaction to that deeply touching and

desperate plea from Siamak Namazi.

VALI NASR, PROFESSOR, SCHOOL OF ADVANCED INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY: Thank you, Christiane. That was a very difficult

interview to listen to. And I really laud Siamak’s bravery and courage and eloquence to reach out and to — not only about his own situation but also

about the circumstances of his fellow prisoners and hostages inside Iran.

I think what has happened to a Siamak, to Emad, and to Morad both cruel and unconscionable. And it is really the responsibility of the Iranian

government to show justice and to release them and right this wrong that has been done to them. But I also think it’s important for the United

States to do everything they — that is necessary to bring Siamak and his fellow prisoners home. And there is a deal that is being a negotiated. End

of the day, it will fall on President Biden to approve the deal, and I hope that the United States will do that and bring them home.

AMANPOUR: Do you know, Vali, the nature of that deal? What would it include? I mean, look, we’ve seen before whether it’s the Americans,

whether it is the Brits, they have got many of their hostages back, the imprisoned nationals back through financial deals, giving back money that

is owed to Iran because of, you know, money that was frozen after the revolution.

What kind of a deal could you envision that might be underway to release this batch of American hostages, Siamak and his fellow detainees?

NASR: From my understanding, this issue has been on the table since at least June of 2021 when the Vienna talks and the nuclear deal was ongoing.

And the deal largely was that in exchange for release of these prisoners, that Iran will have access or get back $7.5 billion of its oil revenue

proceeds that are frozen in South Korean banks.

That deal didn’t go through in the summer largely because the United States’s position was that a deal on the prisoners should happen in tandem

with the nuclear deal. The nuclear deal fell through in September of 2022. And then we ended up in a situation where, you know, you had the protests

in Iran, their — the relationships between Europe and Iran went sour. And it — and western governments, the United States included, are now

extremely skittish about any kind of a deal that would give Iran money because of the backlash in Congress and public opinion in the United

States.

And I hope that in addition to the White House people in Congress and media also hear your interview with Siamak and understand the gravity of the

situation. Unfortunately, there is no way to release these prisoners without some kind of a deal. And ultimately, the White House has to make

that decision, the Congress should support them.

In the past few months, the government of Qatar has stepped in and has been negotiating in directly with both sides, trying to come up with mechanisms

to ensure that the money that Iran would get would only and only be spent on pharmaceuticals and food issues, and that they would not — Iran would

not have access to that money freely.

And as we are speaking, that deal has been going — that negotiation has been going on for some time, it’s probably towards the end. But when all

the technicalities have been sorted out by the Qataris, between Tehran and Washington, of course, Tehran has to make a decision if they are going to

sign. But it really comes down to President Biden also making the decision that he’s going to sign and he’s going to pay whatever political cost comes

with criticisms in Congress domestically. And I hope, again, that he hears Siamak as he thinks about the necessity of making that step.

AMANPOUR: You know, you’re being very forward leaning there. Clearly, you believe in your former government advisor. So, you get the sensitivities

and the complications. Just as a shorthand, as distasteful as it might be to give — to make a deal, as you outline, surely a government, and

particularly a superpower, grown up government, needs to be able to walk and shoot gun at the same time. In other words, to compartmentalize.

As odious as the crackdown on human rights in Iran, as odious as the allegations of sending weaponry to Russia for its war against civilians in

Ukraine, is there not a way, and I ask you as a former government advisor, to say yes, just like with the Soviet Union, we condemned and resisted

communism and its tyranny, but we also had, you know, a hotline, we also had arms control deals and negotiations.

Don’t they need to be able to have a humanitarian outreach and bring back their citizens? How could that not be seen as the right thing to do by

American politicians and American people? But also, to enter a nuclear deal that would keep the world safer?

NASR: Well, I mean, first of all to your last point, if they cannot have a prisoner deal, they’re definitely not going to be able to have a nuclear

deal. And so, there is an urgency to seeing this prisoner done because there’s even larger issues attached to it.

But look, President Biden, end of the day, made a prisoner deal with Russia, with a government that is killing civilians and destroying and

pulverizing an entire country against international law and the president made a deal to — for a prisoner exchange and brought back home an American

prisoner that was held in Russia. And I think that Siamak is right, the president and — of the United States should take that decision.

Unfortunately, dealing with a government like that, of Iran, it means that they are not going to release these prisoners out of the kindness of their

heart. They are going to want something in exchange. Yes, there is going to be criticism of President Biden if he does make that exchange. But the

situation for Siamak and his fellow prisoners is grave. And ultimately, there is moral, political humanitarian responsibility for us to see this

through.

And there is — as we’re speaking, there is a process happening in Qatar. So, I am not privy to where that process is, but I know that at some point

this process ends up on the desk of the president and the president has to sign. And I also do agree with Siamak that the administration has not

really reached out to the families of the prisoners in the way that it should. It has met with many dissidents when the protests were going on in

Iran. But it didn’t take the step of actually talking to the families of those who are held in Iran.

And I do think that there is an opportunity to — at this moment in time, to use the Qatar process to finish this really, really horrendous ordeal

that these prisoners have gone through in Iran and bring them home.

AMANPOUR: Vali, as you know, senior officials responded to a request for comment. And they do say that officials from both the White House and State

Department meet and consult regularly with the Namazi family. Of course, Biden hasn’t.

In June on this program, we had Rob Malley and put the same questions to him, and particularly why Siamak was left out of the previous three hostage

swaps, prisoner swaps that we just mentioned, and that he talked about. This is what Rob Malley —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ROBERT MALLEY, U.S. SPECIAL ENVOY FOR IRAN: He’s right. He needs to come home. He needs to come home. And every day that he is not home is a day

that we have failed in bringing him home. And they recognize it and it’s something that I — we work on as hard as we work on any other issue

related to Iran, if not harder.

Now, the reason he is still there and he is not home is because Iran is holding him as a pawn, because Iran wants to extract concessions, and it’s

unconscionable. Now, we have engaged with Iran through a third-party to try to get him home and we are still making every effort to get him home, him

and his three colleagues and we will continue to do that. And until we’ve done that, we will — we know that we have a very, very heavy

responsibility, that heavy burden to bring them home.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Again, that was in the summer. And just wondering why — and he doesn’t know why. Do you have any idea why he was excluded from the last

three prisoner swaps?

NASR: No, I cannot tell. But Rob is right that, you know, because prisoners are used as pawns, that Iranians or Russians, in the case that

there was also a person that was left behind in this last deal in Russia, want to hold on to these prisoners for a next deal and a next exchange. And

that clearly is unconscionable, as Rob Malley says. But it is the world we are dealing with.

And the American prisoners in Iran and Russia are paying the price for this. And there is a point at which that we have to make a decision that we

have to do everything that we can to arrive at a deal that would bring them home. And I am hopeful that, you know, if Americans are in the White House,

in Congress, in media, elsewhere hear what Siamak had to say today, that they would look at this issue with greater urgency.

AMANPOUR: Really important. Vali Nars, thank you so much for your perspective and your knowledge on this issue. Thank you. And we do hope

something does happen to bring those people home.

Now, as U.S. tensions with countries like Iran grow, our next guest warns that the world could be entering an era of “great power conflict.” One that

could see the United States face off with China and Russia. It is a conflict that he says the U.S. is not yet ready for.

The Wall Street Journal’s national security correspondent, Michael R. Gordon, has been reporting on the United States military for decades. And

he tells Walter Isaacson that America has to come up with new ways of waging war.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, HOST: Thank, you Christiane. And Michael Gordon, welcome to the show.

MICHAEL R. GORDON, NATIONAL SECURITY CORRESPONDENT, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL: Glad to be here.

ISAACSON: You have this amazing piece in “The Wall Street Journal” about how the era of great power competition is reemerging. I mean, we went

through that in the Cold War and then, after, you know, 1989 we thought it was receding (ph) with Russia. And then, 9/11 made it that we are fighting

insurgency. Tell me what you mean about the rise of the superpower confrontations.

GORDON: Well, this, in fact, is the main business of the Pentagon and has it been really since 2018. And following the American wars in Iraq and

Afghanistan and to a certain degree in Syria, against ISIS, there was a stock taking at the Pentagon and a reevaluation of what the next missions

would be. And it was a determined that the Pentagon really needed to gear up for what they called, at the time, a world of great power competition,

which was a thin euphemism for China and Russia. And that was a strategy that was promulgated by then Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, but the Biden

administration has doubled down on it in its own version of the strategy, which he had issued last year.

ISAACSON: And so, does that mean we change the way we procure weapons and do a lot of things with a focus on the fact that we may be fighting Russia

and China now in insurgency wars?

GORDON: It requires a very substantial transformation of American defense in terms of where we put our forces, the kind of military technologies and

weapons that the U.S. buys, the very structure of some of the armed forces has to be rethought. They have to find a way to connect them all up so that

they can share targeting information in real-time.

Because the task of deterring China, which is the primary threat, according to the Biden administration’s Pentagon, is just an enormous undertaking

where you are dealing with a potential adversary, really, that has the homecourt advantage with Taiwan just 100 miles from the coastline of China.

ISAACSON: If you agreed, you know, and you’re a great military historian, but you go back to Thucydides and obviously, Bismarck and Metternich, you

talk about great power competition. But the real warning they always have is never get into a great power competition with two different great power

adversaries, especially when you are pushing them closer to each other.

Aren’t we making that mistake with Russia and China, moving them closer to each other as we become adversaries to both?

GORDON: No, they’ve moved themselves closer to each other. I don’t think you could fault the United States for that. I mean, what’s happened is we

just have to deal with the world as it is, not as we would like it to be. And in this world, China has been — its military might has been growing

substantially. It has a strategy of trying to coerce Taiwan politically to rejoin China and to extend its jurisdiction over that.

At the same time, Vladimir Putin has his own agenda, which we’ve seen play out in Ukraine, to kind of push back NATO. And these two countries have

found common cause with each other against the United States. I don’t know that you could call it a formal alliance, but they clearly see benefit in

cooperating to a certain degree in their kind of broader project to diminish American influence around the world.

So, this is an enormously challenging thing for the Pentagon because it has to be prepared to both deter conflict in the Western, Pacific, thousands of

miles away from the United States, and simultaneously deter conflict in Eastern Europe, halfway around the globe.

And what makes it even more complicated is that China and Russia both study how the United States went to war in Desert Storm against Iraq, and they’ve

devised novel strategies and tactics to try to frustrate the U.S.

ISAACSON: You’ve written a book recently called “Degrade and Destroy,” which is about the campaign against ISIS that we are fighting. The book

comes out in paperback soon. Tell me what lessons we learned from these insurgency wars or maybe bad lessons we learned that apply today?

GORDON: We had advantages in fighting ISIS and in fighting Al Qaeda and even fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan that we don’t enjoy against China.

For example, in those conflicts, we had totally unrivaled, uncontested air supremacy. These insurgent and militant forces didn’t have an air force,

they didn’t really have affective surface to air capabilities. So, we had air dominance. None of that would apply in a war with China.

Second of all, we had bases throughout the region from which we could project power, ground power, air, power and the like. And these bases were

largely immune from enemy attacks, that also wouldn’t be the case in a conflict with China. They’d go after our bases in Japan and Guam, from the

get-go. So, the war against ISIS is a very similar.

But there are some lessons, which is it in the war against ISIS we relied extensively on the Iraqi military, on Syrian forces to be the grand

element. We didn’t put a lot of American forces in combat. There were some, but not a lot. So, we let them do the main fighting. I think that’s the way

of the future for wars in the Middle East. Why is that? Because our main focus is going to be on China and Russia, and if we are going to have to

tangle with militant forces in the Middle East, at least we’re going to want to rely heavily on partners on the ground instead of our own troops.

One exception would be if there is ever a war with Iran.

But I think that one of the lessons is the war against ISIS showed how we need to fight in the Middle East if we are going to put most of our effort

into deterring China and Russia.

ISAACSON: Are we inevitable conflict with China?

GORDON: Well, it’s hard to foretell what’s going to happen in the American relationship with China. But in the case of China, their project to extend

their influence and control over Taiwan is at variance with the American posture and the Western Pacific, which is to defend free trade, to protect

allies like Japan in the region, whose security would be greatly compromised if the Chinese were in control of Taiwan.

ISAACSON: And do you think that President Biden has taken that a bit further, the defense of the Taiwan situation?

GORDON: He is taking it a lot further, because the policy — the official policy is still one of strategic ambiguity. And what is the policy? We

provide arms and weapons to Taiwan. We provide a limited number of trainers. “The Wall Street Journal” recently had a story and how that was

going to be expanded, but it is really a small number.

We are trying to give Taiwan the capability to defend itself against China in order to deter China from ever forcefully trying to take over that

island. Where the ambiguity comes in is the U.S. is left unclear whether we’d employ its own forces to come to Taiwan’s aid. Now, what President

Biden has said on more than one occasion is that the U.S. would. And the Pentagon, in fact, is planning to do so not because a decision to do so has

been made, but because you have to have the plans and the capabilities in hands, in advance, in case your called on to do so.

Now, one thing that’s important to recognize is the Pentagon doesn’t think that China can take Taiwan today. It would be an enormously challenging

task for China. They have to do an amphibious landing, which they’ve never really done. They would have to — China forces haven’t fought with the

Americans, really, since the Korean War. So, it would be — it’s highly ambitious.

And in, fact according to the CIA, the current Chinese military leadership is not confident it could carry out such an operation today. But Xi Jinping

has instructed his own forces to be ready to do so in 2027, according to the CIA. That does not mean they would do so, but it means that he wants to

have at least that option, and a minimum for political coercion, and perhaps more than that.

So, what is going on now is there is a race. There’s a race between the Chinese to get ready to develop this option and there is a race by the

Pentagon to develop the capability to counter the option so the Chinese don’t employ it.

And in this race, we are trying to develop new capabilities and deploy additional forces. And many of these programs won’t come to fruition until

the 2030s. So, the next five years are a pretty anxious period for that part of the world.

ISAACSON: You wrote in your piece about war games, you know, that we play sometimes, and you can explain what a war game is, but it’s something the

Pentagon does. Tell me about the war games that’s been happening on the concept of a struggle in Taiwan.

GORDON: Well, the Pentagon does highly classified wargames or simulations. They’re all done in kind of computer simulations and conference rooms and

in military bases. And in the — my recent article, I recount one that was in 2018, and there is an air force general, it’s Lieutenant General Clint

Hinote. And he had recently been assigned from the Middle East to come back to the Pentagon and be one of the people planning the future of the air

force.

In fact, today, he is in charge of that task, these air force features is what the officers called. And he comes back he told me all on the record

that, you know, he’s — when he first saw the results of the war game of how he would fare in a conflict with China, he’s — the expression he used

was holy crap, you know. We’re going to lose if we fight like that.

ISAACSON: So, what went wrong? What were we missing?

GORDON: Unlike the conflict in the Middle East if you assume that we’re at war with China, our air bases in Japan are going to come under missile

attack almost immediately. Our naval base in Guam is going to come under attack immediately. This is going to interfere with our ability to

replenish subs at seas, and subs are really important.

Our ability to supply our own troops with logistics is going to come under fire, there is a terminology for this in the Pentagon, they call it

contested logistics. None of that was true in our wars in the Middle East. Those — we assemble forces over a period of six months. If you remember

the Gulf War, you know, no one interfered with that. We pick a time on we want to initiate the conflict. And then, we did without any appearance.

Well, that wouldn’t hold in a war with China.

So, what the General Hinote was pointing to was that these assumptions with regard — guided the U.S. employment of force in previous conflicts would

no longer obtained. Therefore, you need a totally new concept for how to do this. You need to have some forces that could survive within range of the

Chinese missiles. That’s what the marines are trying to do now.

You have to have additional standoff capabilities, long-range missiles that you could fire from a safe distance into there. You have to integrate these

capabilities and novel ways. So, it’s not merely a matter of shifting our current military to another part of the world, it’s a matter of coming up

with what the Pentagon calls new operational concepts, new forces and new ways of employing the forces to deal with the threat that’s entirely

different from the one that we’ve been involved with for the past few decades.

And then, you have to factor into this the possibility that, if Russia and China are not formal allies, if were caught up in a conflict in the Western

Pacific, Russia might act opportunistically to pursue some aims in, let’s say, Eastern Europe. And we know the Russians have had a hard going in

Ukraine, but you still haven’t prepared for the contingency that, let’s say, a decade or two from now, they might strike out somewhere else,

thinking we were bogged down in the Western Pacific. So, it is really a very formidable challenge.

ISAACSON: Well, you talk about one of the battles coming up, which is the budget battle. And that’s really beginning this week and next week. And so

many times over the past decade, the budget battles have caused us to spend more, in some ways, on weapons, even as we try to spend less. We spend as

much as the next nine militaries combined and yet, we don’t get a whole lot of bang for the buck. What do you think is the problems we are facing with

our budgeting strategy?

GORDON: Well, I do think we get a lot of bang for the buck. And I feel that the idea of comparing American spending to other countries is just a

little misleading. Because, first of all, we have a professional military that pays a lot more than Chinese military pays. Personal costs eat up a

lot, as does health care. Also, the United States has global responsibilities. They’re trying to deter Chinese aggression and Russian

aggression in totally disparate parts of the world.

There’s no other country that has that as a mission. So, to compare our budget with countries that have niche capabilities and limited

responsibilities, I don’t think is directly relevant. The Congress is sometimes been helpful to the Pentagon.

I mean, here’s an example. They’ve added money to the Pentagon budget in recent years primarily because of their concern over the China threat. So,

when the — last year, when the Pentagon proposed research and development budget of $130 billion, that’s an enormous amount of money, it would be the

highest R&D budgets in Pentagon history. Well, the Congress added 10 billion to that, saying, well, we got to do more on hypersonics and other

technologies.

ISAACSON: The Biden administration has put $25 billion, I think, in weaponry into the Ukraine conflict. Tell me how that’s affected this

strategy in our military readiness?

GORDON: Well, I don’t think it’s affected our military readiness in a bad way. I may have a slightly iconoclastic view on this. Certainly, spent a

lot of resources in Ukraine. But a lot of the weapons, number one, we are giving Ukraine from drawdowns from our own stocks, 155, artillery, shelves,

javelins, things of that sort. I mean, those are not the kinds of weapons U.S. military is going to use in a war with China. We are not fighting a

land war with China. We’d be operating with, you know, long-range anti-ship missiles or marine forces, you know, and anti-ship missiles and the like.

Hypersonic missiles. We’re not going to be fighting trench warfare with the Chinese. So, some of these weapons that are being provided to Ukraine are

not relevant for a U.S. fight with. China.

The second point I would make is, you know, the Russians have lost more than 1,000 tanks. They’ve lost a substantial part of their armed forces.

They’ve had more than 100,000 killed and wounded. Their military capability has been diminished significantly. That’s a positive thing from the U.S.

perspective. So, yes, we’ve given Ukraine a lot of weapons but they’ve been used to diminish Russia’s military capability, at least, conventional

military capabilities to have enormous nuclear capability for, you know, a period of time. So, that is a net plus from a U.S. strategic standpoint.

But here’s the problem for the U.S. What the Ukraine war has shown is that in conventional conflict, weapons can be consumed at enormous rates. I

think much more than the West anticipated. So — and there is a problem with the American defense industrial base, and just keeping the weapons

flowing. I mean, it’s not enough to have small numbers of these things, you have to have massive numbers of these things to keep up the volume of

fires.

So, one of the hurdles to implementing the new strategy is to revamp the defense industrial base. I mean, take submarines, we’re producing about 1.5

attack submarines a year. There’s a deficit of submarines. Submarines are important in the Western Pacific. That’s not a problem that’s easy to

quickly remedy. It is a product of concluding that the Cold War was over and spiking the ball in the end zone a little too soon.

So, these are sort of the bigger challenges that have to be met, if you are really going to make this strategy real. It’s one thing to announce the new

strategy. The Trump administration did that. And so now has the Biden administrations. That’s the easy part. The hard part is implementing the

strategy and doing so consistently over a period of a decade and longer.

ISAACSON: Michael Gordon, thank you so much for joining us.

GORDON: Thank you very much for the opportunity.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And finally, tonight, amid the news of a real strenuous pushback against the Israeli coalitions assault on democracy, there is also a

farewell, a fond farewell to the Israeli actor Chaim Topol who has passed away at the age of 87.

Topol starred as Tevye, the milkman in “Fiddler on the Roof” on stage and on screen, earning him an Oscar nomination. Here he is in a clip from the

film, explaining how we are all just fillers on the roof in our own ways.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CHAIM TOPOL, ACTOR, “FIDDLER ON THE ROOF”: A fiddler on the roof. It sounds crazy, no? But here in our little village of Anatevka, you might say

every one of us is a fiddler on the roof, trying to scratch out a pleasant simple tune without breaking his neck.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And perhaps needed now more than ever, he is Israel’s best-known actor. Topol appeared in works ranging from black (ph) to bond. But after

more than 3,500 performances, to his fans, Topol is Tevye now and forever.

That’s it. If you ever missed our show, you can find the latest episode shortly after it airs on our podcast. On your screen now is a QR code and

all you need to do is pick up your phone and scan it with your camera.

You can also find it at cnn.com/podcast and on all major platforms, just search AMANPOUR. Remember you can always catch us online, Facebook, Twitter

and Instagram. Thank you for watching and goodbye from New York.