Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, HOST: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY live from Kabul, Afghanistan.

Here’s what’s coming up.

The dire humanitarian catastrophe. With half the population facing starvation, I witness the desperate conditions on the ground and ask the

World Food Program if the worst is still to come.

Then, more of our world exclusive with one of Afghanistan’s most powerful and secretive players, the deputy Taliban leader, Sirajuddin Haqqani, on

women’s rights under their regime.

And how women here have to navigate both repression and poverty with the activist Mahbouba Seraj.

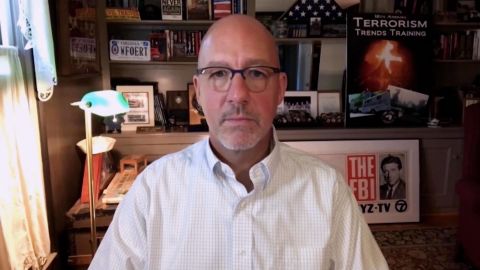

Plus: Domestic terror strikes the United States again. Hari Sreenivasan speaks with FBI agent Tom O’Connor about the mass killing in Buffalo, New

York.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in Kabul.

Afghanistan has fallen off the world map since the Taliban takeover and the chaotic American withdrawal nine months ago. But for almost everyone here,

life has become a daily struggle against poverty. About half the Afghan population face acute food insecurity, with almost nine million the brink

of famine.

And children are particularly hard-hit. More than a million face acute malnutrition, says UNICEF. We also know the root causes, a collapsing

economy exacerbated by international sanctions and a catastrophic drought.

And it’s not hard to find, as we did when we went to a humanitarian distribution center, to a hospital and to a family home. Some of what

you’re about to see is not easy to watch or to accept, but it is essential that we see what Afghans are forced to live with now.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR (voice-over): Under a scorching sun, standing patiently for hours in organized lines, hundreds of newly poor Afghans wait for their monthly

handout, men on one side, women on the other.

Here, the U.N.’s World Food Program is delivering cash assistance, the equivalent of $43 per family.

Khalid Ahmadzai is the coordinator. He says he’s seen the need explode. And right from the start, the stories are dire.

KHALID AHMADZAI, WORLD FOOD PROGRAM: A few days ago, one woman came to me,and she told me that: “I want to give you my son by 16,000 afghani.”

Just give me the afghani. And he was — she was really crying. And that was the worst feeling that I had in my life.

AMANPOUR (on camera): Are you serious?

AHMADZAI: Yes, this is a serious thing that we had a distribution at the first day. So, the hunger is too much high here.

AMANPOUR: You know, we have heard those stories, but I have never heard it from somebody who’s actually seen it.

AHMADZAI: Yes. Yes. Yes, I have seen it. It’s too much bad. And it hurts me a lot.

AMANPOUR (voice-over): Everyone we met is hurting. According to the International Rescue Committee, almost half the population of Afghanistan

lives on less than one meal a day. And the U.N. says nearly nine million people risk famine-like conditions.

Fereshtah has five kids.

(on camera): And how many meals per day can you eat?

(voice-over): “When you don’t have money,” she tells us, “when you don’t have a job, you don’t have income. Would you be able to eat proper food

when there’s no work?”

Khatima is a widow. “They should let us work because we have to become the men of the family, so we can find bread for the children. None of my six

kids have shoes. And with 3,000 afghanis, what will I be able to do in six months’ time?”

(on camera): You just want work.

(voice-over): “I have to work,” she says.

At this WFP distribution site in Kabul, you do see women working and women mostly with their faces uncovered. Outside, Taliban slogans plastered over

the blast walls tout victory over the Americans and claim to be of the people, for the people.

But while security has improved since they took over, the country is facing economic collapse. And that shows up all over the tiny bodies we see at the

Indira Gandhi Children’s Hospital. It’s the biggest in Afghanistan, now heaving under the extra weight.

Dr. Mohammad Yaqob Sharafat tells us that 20 to 30 percent of the babies in this neonatal ward are malnourished. Suddenly, he rushes to the side of one

who stopped breathing. For five minutes, we watched him pump his heart, until he comes back to life, but for how long? Even in the womb, the deck

stacked against them.

DR. MOHAMMAD YAQOB SHARAFAT, INDIRA GANDHI CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL: From one side, the mothers are not getting well nutritions.

AMANPOUR (on camera): Wow. So it’s a triple whammy. The mothers aren’t nourished enough.

SHARAFAT: Yeah.

AMANPOUR: The economy is bad.

SHARAFAT: Bad.

AMANPOUR: They have too many children.

SHARAFAT: Children.

AMANPOUR: And they’re overworking themselves.

(CROSSTALK)

SHARAFAT: So, all these factors together make the situations to they give birth premature babies.

AMANPOUR (voice-over): Because they’re under sanctions, the Taliban are struggling to pay salaries. So the International Committee of the Red Cross

pays all the doctors and nurses at this hospital and at 32 others across the country. That’s about 10,000 health workers in all.

(on camera): Look at this child. He’s 2.5 years old.

(voice-over): His name is Mohammed. He’s malnourished.

(on camera): How much food is she able to give her child at home? Why does he look like this?

(voice-over): His mother says she’s had nothing but breast milk to feed him, but now can’t afford enough to eat to keep producing even that.

It’s the same for Shazia. Her seven-month-old baby has severe pneumonia, but at least she gets fed here at the hospital, so that she can breast-feed

her daughter.

“Back home, we don’t have this kind of food, unfortunately,” she says. “If we have food for lunch, we don’t have anything for dinner.”

(on camera): While we’re here, the electricity has gone out.

(voice-over): “It happens all the time,” the director tells us.

We watch a doctor carry on by the light of a mobile phone, until the electricity comes back. We end this day in the tiniest dwellings amongst

the poorest of Kabul’s poor.

Waliullah and Basmina have six children. While she prepares their meal of eggs, two small bowls of beans and two flatbreads, the 8- and 10-year-old

are out scavenging wastepaper to sell and polishing shoes. It’s their only income, since Waliullah injured his back and can no longer work as a

laborer.

He tells us their 10-month-old baby is malnourished.

“I always worry and stress about this,” says Basmina. But she tells her kids: “God will be kind to us one day.”

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: One day, perhaps. That has been the story of Afghanistan for decades now.

Mary-Ellen McGroarty is the World Food Program director here. And she’s joining me now.

What we saw was really heartbreaking. And that’s just one or two days of bearing witness. You have been here for months and months and months. Just

give us a sense of what it’s like now.

MARY-ELLEN MCGROARTY, AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY DIRECTOR, WORLD FOOD PROGRAM: Yeah, I mean, it still continues to be heartbreaking.

We just had the new assessment that came out last week. So we’re down at under 20 million of acute food-insecure.

AMANPOUR: So is that better?

MCGROARTY: This is a bit better.

The massive scale-up that we have done over the last couple of months with humanitarian food assistance, thanks to the incredible generosity of the

international community, we have been able to reach 17 million people since January, phenomenal numbers, but needed numbers.

But it still, still continues. They’re not out of the woods in Afghanistan yet, because the main drivers of food insecurity haven’t changed. We’re

waiting on the harvest in June and July. We’re hopeful that it will be a better harvest than last year.

But, still, some of the rainfall hasn’t been good. But the economic crisis continues. And when I walk — when I go out across the country, that’s what

I hear.

AMANPOUR: So let me just read you these stats.

MCGROARTY: Yes.

AMANPOUR: We have got lots of stats, but they are actually kind of mind- boggling.

We have got a graphic to show just how dire it is, according to your organization and others. You say you have adjusted down to about 20

million.

They face acute hunger; 20,000 are at the most extreme level of food insecurity, which are like about famine-like conditions. And according to

UNICEF, 1.1 million children are expected to suffer from severe, severe wasting this year. That’s nearly double the number in 2018.

We were told at your food distributor — your aid distribution center that some of these people had never waited in line for handouts, had never had

to have handouts over the last 20 years.

MCGROARTY: Yeah, I mean, I have been here since August, as you know, over the last nine months. And I have traveled out across the country.

And I have met farmers who have told me, through the decades of war, they never had to stand in line for humanitarian assistance until now. I have

met many, many women who — even female head of houses, widows, who were able to fend for themselves. And it’s just all imploded for them.

That collision of the drought and the economic crisis, the legacy of COVID — I mean, I was in the Wakhan Corridor last week. It’s one of the remotest

areas in Afghanistan. And, there, they were telling me how the impact of COVID around the tourism, the small bit of tourism they had, the economic

crisis

You think — you look at the big numbers, and you think, in this remote area, they’re not going to talk about the economic crisis, but they did.

Every village I was in, I met people who lost their jobs. I met teachers who couldn’t go to work. I met women who couldn’t go to work.

And then climate change and the impact on props, so, yeah, I mean, it’s just that whole collision of factors coming together.

AMANPOUR: Talk to me about women, because you mentioned women who used to be able to fend for themselves and now can’t.

One of the reasons, apart from all the natural disasters and the economic collapse, is because many have been forced out of work. There’s a chilling

effect since the Taliban has come. And I wonder how you notice that and how it affects the humanitarian distribution.

What could or should be done for women specifically?

MCGROARTY: Yeah, I mean, women are bearing the brunt of hunger in Afghanistan.

I mean, after decades and decades of conflict, we have old widows, we have young widows, we have middle-aged widows trying to fend for themselves and

trying to fend for their family.

What I’m seeing across the country when I go out, as I meet many young women who are the only breadwinner in the family who can’t go to work, it

is absolutely heartbreaking to hear from them. Our priority is that women can access the humanitarian assistance and also that our staff can continue

to come to work.

AMANPOUR: So let me ask about your staff, because, again, we hear the edicts.

We don’t see them yet, at least not here in Kabul, forcefully enforced, like the edict on the full body covering. That’s confusing. Is it a full

body covering? Is it a head scarf? What is it? I asked the leader about it. And yet there are posters stuck up, even apparently on some U.N. walls.

So, what is the situation? We witnessed women working at your distribution center, and women there, some of the beneficiaries, not feeling they had to

cover their face. How is it working right now in that regard?

MCGROARTY: Yeah, we’re monitoring it very closely.

And it’s landing quite differently across the country. As you said, you were in a distribution site today, and you saw female staff working, and

it’s great, and women accessing humanitarian assistance.

When I was out in the Wakhan Corridor last week, women are worried about being able to access the market by themselves. They’re worried about going

to the fields by themselves. They are worried about going to the well by themselves. But, most particularly, they are worried about going to health

centers and nutrition centers with their young children by themselves.

So…

AMANPOUR: Since the takeover, because they have been told they can’t leave without male escorts; is that right?

MCGROARTY: Yeah, that’s what they’re — yeah.

And there’s a lot of self-censoring. And there’s — there’s fear as well about going out. I mean, yes, some women are braver than other women. But a

lot of what I met last week, this is really their concern, about going to the fields, going to the market.

And, for us, our major concern is that women right across Afghanistan are able to access humanitarian assistance, services, nutrition services, and

also being able to work.

AMANPOUR: And what is your relationship with Taliban, particularly, I mean, as a — well, a woman, and also as WFP representative here, a major,

major necessity for them, because they can’t provide the wherewithal for their people?

MCGROARTY: Yeah.

I mean, I engage with the Taliban at the national level, at the provincial level, when I’m out. I engage so that we have the humanitarian access that

we need, and that we have principled humanitarian assistance. So, I talk to them. I inform them on what we’re doing, just to make sure that we have

that humanitarian space.

AMANPOUR: And?

MCGROARTY: Yes.

I talk to them. I…

AMANPOUR: Any restrictions?

MCGROARTY: No.

I mean, you have issues here and there in a complex operation like Afghanistan and the scale of the operation. But, in most cases, we’re able

to solve the problems. We have over 2,000 distribution sites across the country. We’re across all the 34 provinces. And, on the whole, we’re able

to get to the people we need to reach .

AMANPOUR: Now, we said and we asked the question, will this humanitarian crisis, in terms of food insecurity, will it get worse? Or have you broken

the back of the worst?

I know you were terrified in the winter that the cold weather, the lack of food could see a massive death toll?

MCGROARTY: Yeah, I was terrified in October, I mean, what we were looking at.

And, thankfully, the donors, the international community stood up and really enabled us and enabled the humanitarian community to scale up at a

massive scale that got us across the winter. We’re now hopeful of the harvest, as I said.

But, at the same time, we still have a humanitarian crisis. We need a couple of things in Afghanistan. We need to continue with the pressure on

the humanitarian crisis and get people back from the cliff edge. But, at the same time, we need to be building household resilience, community

resilience.

So, we need a two-tracked approach at both scale — if you’re hungry today, you need to eat today, and you’re hungry tomorrow. Seeds take a couple of

months to grow. So we need the agriculture inputs. We need jobs to come back, of course, because that’s what I hear.

That’s what frightens me. You know, with the drought, there is some hope with the rain and everything else. But when you hear right across the

people telling you, we have lost our jobs, you think, what’s going to happen?

AMANPOUR: And, lastly, are you concerned that there’s Afghanistan fatigue or Afghanistan ignoring syndrome since the fall — since the withdrawal of

the U.S. and since the war in Ukraine?

MCGROARTY: Yeah.

I mean, it is worrying. So, it does — and there’s not only just the Afghanistan crisis. There are many crises across the world. But when I’m

sitting here, and when I go out, and when I talk to people, and I’m just hoping the international community, please, don’t forget Afghanistan, and

there are — a need.

They’re in a situation not of their own making. It is a lottery of birth. You and I are lucky where we were born, right? You meet many of the — many

of the people I meet today, and they’re Afghan, and they’re in a situation. It’s been — the peace dividend is a very sad peace dividend for the people

of Afghanistan.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

MCGROARTY: And I really hope the international community continue to give us the support and give the people of Afghanistan the support they need.

AMANPOUR: Mary-Ellen McGroarty, WFP coordinator here, thank you so much, indeed.

MCGROARTY: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: So, yesterday, we brought you part one of my exclusive conversation with the deputy Taliban leader.

Now he’s the interim interior minister, Sirajuddin Haqqani. He told me that he’s committed to women’s rights within their framework. And he says the

Taliban order that women cover themselves from head to toe in public is really just advice, not a decree.

But the posters we see here on the streets of Kabul illustrate the pressure on women to conform. Haqqani told me this rare interview is to make himself

and the government visible to Afghans and the world.

Here’s part two of our exclusive conversation.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Did you ever expect the international community would be so firm in putting the rights of women so central to the conditions for recognizing

you, amongst other things, but women’s rights very central?

SIRAJUDDIN HAQQANI, ACTING AFGHAN INTERIOR MINISTER (through translator): I wish the world, and instead of sanctions, had done some research and came

to an agreement with us and had some understanding.

It is possible that they may have been satisfied with us. But now the situation is reversed. Under the current circumstances, judgments,

research, and decision-making are all one-sided. The point is that the interpretation of the current situation is not accurate.

And instead of seeing Afghanistan from a specific angle, from far away, they should come to take a closer look at the situation inside Afghanistan.

Communicate with us. Come to a mutual understanding with us. We are still at the preliminary phase. It has barely been eight months since we took

over the government.

Our government assumed power in a situation when everything had almost collapsed. We are yet to bring the situation back to normal. Therefore,

such an interpretation is not true. Instead, there should be discussions. This will be better, because all such concerns could be easily resolved

through dialogue and mutual understanding.

AMANPOUR: Can I just get it very clear? Does your government accept that women need to work? It’s half the population. You are in dire, dire

financial stress.

Women have the right to work under Islam and before you came here. You want to be known as a government for everyone, a legitimate government. Do you

accept that women have the right to work?

HAQQANI (through translator): Yes, within their own framework.

AMANPOUR: Which means what, in their own framework? Can they be lawyers? Can they be judges? Can they run for Parliament, like they used to?

I know they’re working in hospitals. I know there’s some teachers working. I know they’re working in civil service and in your — in your ministry.

But many tell us that they feel that the Taliban wants them to stay at home. And they’re afraid of some of the edicts that has a very chilling

effect.

HAQQANI (through translator): We keep naughty women at home.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: OK, you need to explain that joke, because people will think that’s official policy. And maybe it is.

What does that mean, naughty?

HAQQANI (through translator): What I am saying is that the international community is raising the issue of women’s rights a lot of.

Here in Afghanistan, there are Islamic, national, cultural and traditional principles. Within the limit of those principles, we are working to provide

them with opportunities to work. And that is our goal.

By saying naughty women, it was a joke referring to those naughty women who are controlled by some other sides to bring the current government into

question.

AMANPOUR: OK, so what you mean is women who are protesting their legitimate rights? Because your ministry and your police have been cracking

down on them.

So are you saying that women or any other group have no right to protest for their rights?

HAQQANI (through translator): To talk about this issue, the moment, the relationship between the new government in Afghanistan and the

international community is not based on official interaction, which has caused many people to lose their jobs and pushed them into poverty.

So, movements are being provoked against the government from outside. Nevertheless, all these problems will be peacefully resolved with the

passing of time.

The current poverty and unemployment have not only affected women in Afghanistan, but it has also affected many others. Even half of our

mujahideen comrades have not been employed yet. The single issue of women’s right has been put forward. But, in general, what has created all these

obstacles is the sanction and the lack of official interaction with the world community that has also pushed many people into poverty and

joblessness.

AMANPOUR: Now, you may think that about women’s rights, but I still have heard that there are some very conservative leaders of the Taliban, mostly

in Kandahar, who don’t believe in women’s rights.

And I guess I want to know, is there a split in the Taliban? And is the Taliban still an ideological movement, or is it — are you trying to be a

governing, pragmatic body?

HAQQANI (through translator): There is no division and the government to split Kabul from Kandahar.

You may have seen statements from Sheik Saheb, supreme leader, about how committed he is to women’s rights. However, they might be different

expectations and ways of thinking.

If you look at the other countries too, you can see that there are different viewpoints. This is a baseless statement that there’s a split

among the Taliban. There’s a single ideology to ensure and safeguard the rights that Islam has given to women. And no one is opposing it. But it’s

just a matter of how to approach it.

For instance, in Afghanistan, there are people, as you mentioned, who have viewpoints like the ones in the previous governments that had different

approach. Then there is the Islamic emirate, which has its own rules, which have been and will be proposed.

The Islamic emirate is committed to safeguarding the rights of women.

AMANPOUR: One last question this issue. The world got very upset because there was an edict this past week or so which said that all Afghan women

had to cover their faces and were the long chadori. They call it a burqa.

Is that right? Do all Afghan women have to cover their faces?

HAQQANI (through translator): If we talk about the edict, there is hijab, education and what? A hijab is an order according to the Islamic Sharia.

Since the claim of our movement was that what we wanted, the implementation of a sacred Islamic government system in this country, within the Islamic

government, we are committed to the rights of everyone. We are not forcing women to wear hijab, but we are advising them and preaching to them from

time to time.

Hijab is also creating a dignified environment for women’s education and work. Hijab is not compulsory, but is an Islamic order that everyone should

implement.

AMANPOUR: OK, that’s interesting.

You are still called an acting government, an interim government. And when you first came in, you said that: “We would agree on a new inclusive

political system in which the voice of every Afghan is reflected and where no Afghan feels excluded.”

That’s from what you wrote. But that hasn’t happened. There is no movement towards bringing in other political parties, to bring in other members of

the, I don’t know, previous government, different ethnicities, different parts. You know what I’m saying;.

Is there — are there any elections planned? Will there be a Parliament? What is this country going to look like? Will there be democracy?

HAQQANI (through translator): About inclusivity, I said earlier that, if the transition of power had happened in a peaceful manner, a lot of

challenge would not have existed.

Here, blood was used to abandon the Afghan society in an environment of mistrust. By inclusivity, if we are referring to the inclusion of people in

the government from Afghanistan’s different ethnicities and tribes, that has already been implemented. But those officials who were part of the

previous regime, for us, gaining their trust and ensuring their security was more important than including them in the new government.

We have been working to build trust among those people. But the decision to replace the current acting government with a permanent independent one lies

with our leadership to make and depends on our relations on international economic and security levels.

Once an environment of trust is established, this is going to happen.

AMANPOUR: When you said there’s going to be new government, will there be elections? I forgot to ask you that. Will there be elections for a new —

for the permanent government?

HAQQANI (through translator): That is a premature question.

AMANPOUR: OK.

Well, we will be watching.

Thank you for your time. Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani, thank you for joining us today.

HAQQANI (through translator): Thank you very much.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: A lot to digest there.

And, afterwards, his aides said that this interview was designed to open a new chapter with the West and the rest of the world. Well, we will see.

The Taliban has just announced that it will dissolve the Human Rights Commission and other key agencies. They blame budget issues.

It is not easy to speak out for women’s rights, but Mahbouba Seraj is bravely making her voice heard. And she’s insisted on staying in her

country, although she often travels abroad, drumming up support for the women here. Tonight, she’s at a conference in Brussels, from where she’s

joining me now.

Mahbouba Seraj, welcome to the program.

Can you just give me your impressions of what you heard from Sirajuddin Haqqani, who is the most senior leader, frankly, in the government right

now?

MAHBOUBA SERAJ, AFGHAN WOMEN’S RIGHTS ACTIVIST: Thank you, Ms. Amanpour, for having me on your show.

I find — I find the whole thing — I find it interesting. That’s all I can say at this point, because I am looking at the situation that, as the

people of Afghanistan, as the citizens of that country, and as the half of the population, how different we look at the whole situation of men and

women, and rights, and what is ours, and an Islamic interpretation and everything that they’re talking about.

I mean, the difference is like a day and night amongst us. And, also, the question of one other thing, which is — what is also very interesting,

that Mr. Haqqani said is the question of trust.

The same way that they do believe that they don’t have any trust with — towards the international community, neither the international community

towards them.

Well, the same thing goes, you know, with the women of Afghanistan at this point. There is no trust amongst us. There is fear, of course, there is

fear. Because a reason why there is fear, is because we can die in a second. They can come and kill us. So, that fear from death is the only

thing holding a lot of us women, you know, from standing up, from talking, from singing, from doing. And at the same time, we are dying all the time.

And the reason why we are dying is because we don’t get access to food. Our children are dying. Our families are dying. Our young girls are dying — I

mean, are going to be so depressed that, you know — I mean, there is the rate of suicide that has gone high in this country but nobody is really

looking at. So, everything is getting very strange in every way. And that is because in that level, we don’t trust each other. They don’t trust us.

And then they don’t want to talk to us.

AMANPOUR: Right.

SERAJ: And not only to us —

AMANPOUR: OK. So let me —

SERAJ: — talk to the people of Afghanistan.

AMANPOUR: Sorry, I just want to break in and ask you a question along the lines that you’re laying out. Look, first and foremost, Mahbouba, we tried

to get an Afghan woman to come and speak to us right here in Kabul.

SERAJ: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And we had very, very little success. In fact, none. None. No success. That is why we are talking to you. And we wanted to talk to you

because you’re an Afghan woman who still lives in this country. This is what an aide, an international official told us who works on women’s issues

here today. Basically, said, alas, all are too terrified. A terrible reality and unfortunate that diaspores take the lead. So, we do know that a

lot of brave Afghan women who fled are taking the lead in raising the voices for the support of the women here. But the fact of the matter is —

well, let me just ask you, first and foremost, are you worried for your own security? Your own ability to keep, you know, doing this back here in Kabul

if you speak out?

SERAJ: Well, Ms. Amanpour, I have made a promise to myself. And the reason why I’m staying in Afghanistan is because of that promise. The women of

Afghanistan, whether the Taliban knows that, believe that, or don’t believe that or whatever which way they are looking at it. They really do need me.

And I need to be there in order to get the help that I can get to them. In order to raise their voices in the world. In order to raise their concern

in the world. Because, you know, our lives, has not stopped in Afghanistan.

The woman of Afghanistan’s lives have not stopped in Afghanistan because the Taliban have come in, you know. There are things that still we can do

and we have to do. And I made a promise that we are going to do that. I want to look after them. I want to be their voice, whoever one of them that

needs me and wants me. The ones that don’t want to, God be with them. it’s OK.

But otherwise, you know, this is a promise that I made to myself and I made to Allah. So, this is what I am doing. And by doing it, the way I am doing

it, I’m trying to be respectful of everybody. I am trying to consider the rights of everybody. At the same time, you know, giving — the Taliban can

raise their voices and say anything they want to the world. We should have the right to be doing the same thing. We should have a voice. We should

raise our concerns. We should say that you know, these are the things that are wrong.

Like, for example, regarding the — you know, the burqa and covering our faces. This is something that there is one interpretation that the face

should be covered. According to Qur’an and according to what we know, in our Hanafi, you know, part of the religion because we are Sunnis. You know,

it’s a discussion that —

AMANPOUR: Mahbouba, I’m not sure whether you can still hear me. I don’t hear Mahbouba anymore. Maybe it’s because I’ve lost connection. But she

seems to be still talking. Can you hear, Mahbouba?

SERAJ: I’m here though.

AMANPOUR: I can’t hear. We’re just having some audio difficulties. But we are going to get back to you. There we go. I think I can hear you.

SERAJ: All right.

AMANPOUR: Yes, I can hear you. Listing, you know, this is the reality of being here. Mahbouba, let me ask you this.

SERAJ: What?

AMANPOUR: The fact of the matter is, as you know, that many Afghan women who have been educated, who have — had jobs over the last 20 years. Who

are professionals, who are activists, who are elected officials here, et cetera, et cetera. Those who could have fled. But, but, tens of millions of

Afghan women will not be able to leave the country.

SERAJ: No.

AMANPOUR: Have to keep living here. Have to live under this government. So, how do you —

SERAJ: Exactly.

AMANPOUR: — see a way forward? And do you see any possibility, even if somebody like yourself, engaging, for instance, with Minister Haqqani after

what he said publicly?

SERAJ: I would love to. I would love to sit down and talk to him. I do believe in having communication. If we don’t talk, if we don’t sit down

across from a table and talk to each other, how are we going to make any difference?

Well, God has created us, gave us humanity in human beings, a brain and a tongue. And both of these have to be used. We have to talk with our tongue

and we have to think with our brain. God did not say that you because you’re a woman, you’re stupid. And a man is more intelligent. God did not

say that. God said you are both equal. The one in my eyes, closer to me, is the one that has more (INAUDIBLE) and has more belief in me, and that

worship me more. That’s the only — the only difference.

Otherwise, you know, what is the difference? What is the difference? I can talk. I say my prayer. I’m a good human being. So are all the women in

Afghanistan. What did they do wrong? What did they do wrong? They have no right to live? Why? They can’t breathe the air? Why? They shouldn’t eat?

Why? They can’t go to school? Why? They cannot work? Why? Could somebody, somebody please tell me? Why? Why? That’s all I’m asking. Why is it that

the brother of mine has the right? Why is it that, you know —

AMANPOUR: Mahbouba, can I ask you —

SERAJ: — my son. And my daughter does not have the right, why? You know.

AMANPOUR: OK.

SERAJ: This is —

AMANPOUR: Mahbouba Seraj, thank you so much indeed for joining us. Thank you.

SERAJ: You’re very welcome. Thank you.

AMANPOUR: Very powerful. Thank you so much for being with us and we hope to see you when you get back here.

And while the U.S. government has always been laser-focused on the global war on terror, even here, of course, domestic terror driven by racial hate

has been growing exponentially. Today, President Joe Biden and First Lady Jill Biden paid their respects and visited the families of the victims of

Saturday’s mass shooting in Buffalo, New York. This is what he said.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOE BIDEN, U.S. PRESIDENT: Jill and I bring you this message from deep in our nation’s soul. In America, evil will not win, I promise you. Hate will

not prevail. And white supremacy will not have the last word.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: 10 people were killed. While authorities say it was a racially motivated attack by an 18-year-old self-described white supremacist. Tom

O’Connor is a domestic terrorism expert and retired FBI official and he is joining Hari Sreenivasan.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

HARI SREENIVASAN, CORRESPONDENT: Christiane, thanks. Tom O’Connor, thanks so much for joining us. You have been investigating so

many different forms of terrorism, especially domestic terrorism, for so long now. When you hear that a mass shooting like this happens, most of us

would immediately say this person is not in their right mind, right? That this person went out of their way to make sure that he was telling the

world that he was in his right mind. When you look at what motivated him, it’s not so different from — or it is exactly the same as what so many of

these shooters say.

TOM O’CONNOR, FBI SPECIAL AGENT (RET.): Well, if you’re able to read the manifesto, it really is taken from numerous other shooters or domestic

terrorists, pieces of their ideology. And it goes all the way back to a man named David Lane who was part of The Order which was a terrorist group that

robbed banks in armored cars and killed Alan Berg, a Jewish talk show host, in San Francisco — excuse me, in Colorado.

And this ideology, the 14 words of David Lane, is in that person’s building of why they did this, right. So, it is so many different ideologies that

have been built into this. It’s nothing new, unfortunately. This Great Replacement Theory has been weaved in throughout many different very sad

events and attacks that have taken place in the United States.

SREENIVASAN: You know, I asked a question about ideology and whether there is something that binds these things together because we often have a

tendency to look at these as lone-wolf actors. And I think that minimizes the connection that actually exists. That this isn’t just an individual by

themselves that there is an idea and, you know, if you don’t kind of root that, then you’re going to have more of these.

O’CONNOR: Well, you know, we talked about lone actors, lone-wolf actors. I don’t know if there is such a thing as a lone-wolf actor any longer. With

social media being so prevalent and the ability to communicate on encrypted apps, on social media platforms. People are pulling from narratives and

conspiracy theories and radical ideologies to build themselves to the point where they attack.

So, that person may have no human contact with a group or individuals. But clearly, in this case, that person had contact through, whether it be

historical readings of the Christ Church shooters’ background. So, it wasn’t done in a vacuum.

SREENIVASAN: He even laid out how he was radicalized. He tells you which sites that he went to and what sorts of things that he started to read and

then how he felt that he was getting the truth or his eyes were open. I mean, you know, what was interesting to me is you could substitute what he

is saying with someone who was a terrorist in a different part of the world, who was radicalized by listening to speeches online. It’s the same

thing.

O’CONNOR: It really is the same thing. You know, if you’re using force or violence to intimidate or coerce a civilian population or to influence the

policy of a government, whether you’re ISIS, Al-Qaeda, or a person who is driven by the Great Replacement Theory, the White Power Movement the act is

the same. If you walk into a store and kill a number of people, what is the difference between a white terrorist and someone from another race who does

this? It is — it’s terrorism. It’s what has driven the person to this.

And as you said, they go online. They become, you know — they believe everything they read. And they really go to an echo chamber of people who

already believe what they believe and it just reinforces it. The sad part is that the rhetoric that is out in the normal, we call it mainstream, has

taken in some of this so that this radical theory of the Great Replacement, the White Genocide has seeped its way into a much more mainstream rhetoric

and conspiracy theories.

That because of the ability to do “Research” on the internet, people are going down that rabbit hole much, much easier than they would in the ’90s,

early 2000s when people had to literally go to a meeting and sit down. They had to have that contact with someone. Now, they do have to do that. They

don’t have to leave their own houses. And as this person laid right out that they — that’s how they radicalize. And that’s how they got to the

point where they felt that they had to act.

SREENIVASAN: So, let me ask the question, I guess, that most law enforcement are probably struggling with. Which is, how do you protect the

First Amendment which protects this type of speech, but intercept these actors before, hopefully before, they commit a mass tragedy like this?

O’CONNOR: Right. So, that is the million-dollar question. Because when you’re talking about international terrorism, ISIS, Al-Qaeda, the big

players that we talk about, they don’t have the protection of the constitution if they’re coming from another country, right, to attack us.

When you talk about domestic terrorism, domestic terrorists, if they’re U.S. citizens, they enjoy the rights under the constitution. And the First

Amendment is not called the First Amendment because it’s kind of important. It is the First Amendment. And, you know, in many cases, there are times

when there may be a — I wouldn’t call it a red flag but a flag. And that flag really can’t be investigated or looked at very much because it is

First Amendment protected.

And the First Amendment, you know, with the FBI as the lead for counterterrorism, the First Amendment wins. And it should because we have

to be very, very careful. That slippery slope of going down and investigating people for that free speech, for that peaceful assembly. If

you start eroding that First Amendment, where do you stop, right? Because, you know, the speech that you don’t enjoy or I may disagree with, you still

have a right to say it.

The bottom line is, it’s the violence. And it’s the violence that crosses you past that First Amendment. And to be able to find that there’s a

potential for violence, sometimes it is not as clear as, you know, the person made a statement. I can be — it’s a very, very fine line that the

law enforcement has to walk. And the First Amendment should always be the winner in that. And sadly, that means that potentially something may get

by.

But there — they — I guarantee you, they are working every single day to try and make sure that those potential for violence is intercepted in some

way that they can get in front of that violence so that it doesn’t take place.

SREENIVASAN: I understand why the security apparatus in the United States after 9/11 shifted to look at the rest of the world, because we perceived

our threats to be primarily from outside. And I don’t think those threats are gone.

O’CONNOR: Not at all.

SREENIVASAN: But I am saying, in the past several years, America has been repeatedly attacked in this way from inside, and I’m wondering whether we

have equal amount of resources dedicated to trying to figure out how to get to the domestic violence terrorist that exist in the U.S.

O’CONNOR: Well, when — your example is spot on. After 9/11, resources were shifted in law enforcement and the FBI across United States government

to address those potential threats and threats from international terrorist.

There — that doesn’t mean that they hired thousand new agents to go work international terrorism. That meant that they took agents from other

violations and move them to international terrorism. And I don’t disagree with, that that was a threat. 9/11 was horrendous and we needed to be on

top of that.

Sadly, there were not as many of us left working in domestic violent extremists. And it was across United States government, a second-tier

violation. And I think anybody who worked these types of violations would agree with that.

And you have to look at it, if you look at the violations for international terrorism to be able to charge people with acts of international terrorism,

there is a plethora of charges that can be brought. If you look at the definition of domestic terrorism and using forcer violence to intimidate a

course of civilian population or the influence of policy of a government, that is the definition.

There is no penalty. No one is being charged with domestic terrorism. You see people charged with hate crimes, and that may very well fit. But

domestic terrorism may fit also. There are no — is no penalty in the United States for the vast majority of acts under domestic terrorism.

People are charged with shooting, charged with homicide, they are charged with state and local crimes, but there is no penalty attached to the

definition of domestic terrorism.

So, that is a fact, which it is, how serious are we taking this problem if we don’t even have a penalty for it? People are charged, they’ll go to

jail, but I still think we need to say this person is a domestic terrorist. And I think that in the United States and domestically here, we have a

difficult time saying, my next-door neighbor maybe a domestic terrorist. But if you show up and shoot people for a political reason, that is

terrorism.

If you yelled Allahu Akbar while you were doing that, people would have no problem calling it terrorism. But because it is one of us, they have a

difficulty with that. And the law has a difficult problem with that. They can’t — we have not come to the point where we say, domestic terrorism is

against the law. And I think that that is an issue.

How do you regulate or review the number of domestic terrorism cases in the United States if there is no way to do that? You can look up the number of

international terrorism arrests, of convictions. Look up domestic terrorism, arrests and convictions, you won’t find any because there is no

penalty.

SREENIVASAN: So, if it is on Congress to even come up with the penalty for domestic terrorism, I wonder then whether we have the political will?

Because there is a recent poll out, Associated Press-NORC did a recent poll that found that one in three Americans and 50 percent of Republicans feel

that there is a deliberate attempt that native born Americans are going to be replaced by immigrants.

O’CONNOR: It is the mainstreaming of a very radical ideology. Clearly, it has led people to use extreme force of violence in an effort to stop that

white genocide. And it is the mainstreaming of that which has made it much more acceptable for the average person in the percentages you just

mentioned.

SREENIVASAN: Recently, we just had Representative Liz Cheney said about that her own party, that she holds the GOP leadership responsible to enable

this kind of white nationalism. Regardless of your party affiliation, at some point, it just seems irresponsible to stay silent when this is

happening.

O’CONNOR: Well, I think you’re right. I mean, Liz Cheney is a very conservative person and she is, at least, saying that, hey, words matter

and it’s wrong to push this theory into your news conferences you’re your mainstream, and there has to be some responsibility for that. And I was

glad to see her do that, break — come out with that statement.

But, you know, there has been — there have been attempts to bring a penalty to domestic terrorism. I would love to see that happen. I don’t —

I honestly don’t see it happening because of the polarization in the United States right now. Acts such as this should be — it shouldn’t have a

political bent, there should be not left and right saying that, oh, I get that this is wrong, but the violence is the violence. I don’t care if it

comes from the left or if it comes from the right.

SREENIVASAN: Tom, I kind of want to look at in the arc of your career, when you think about how America was positioned to tackle these 10 years

out, 15 years ago versus today, do you feel like there is a potential for it to get worse now or, I mean, do you see the possibility of another

Timothy McVeigh style attack?

O’CONNOR: Well, you know, I’ve said it many times, right now, the environment we’re in, the polarization within the United States at this

time and the use of social media, which was not there in the ’80s and ’90s, early 2000s, the ability for people to, you know, view this radical thought

and buy into it is worse now than it ever has been.

If you look at individuals, the potential for people to go to the point of using serious violence, I think that the potential is there for this to

occur more frequently than it ever has and the potential for the Timothy McVeigh type of a mindset. If you look at the personal grievances that were

there in the ’90s, when Timothy McVeigh blew up the Murrah Federal Building, killed 168 people, including 19 small children, it was — the

economy was bad, he felt the grievances related to the overreach of the government.

So, all of these things, if you look now, you have an economy which is not good. If you look at the restrictions in place by the government for the

pandemic, this is believed to be an overreach. The mandates for the shots, overreach of the government. I mean, the gas prices, all of these things

work into a person’s personal grievances. All of these things that are — the pressures that are coming onto people. They don’t wake up and say, this

is all my fault. It is usually the government’s fault, right? The president that is in power, the Congress that’s in some power.

So, people — the anti-government sentiments right now are higher than I have seen them in the 23 years that I work domestic extremism. And there

have been ebbs and flows, but it’s higher now than it has been. So, I think we need to take it very seriously and we need to make sure that we get in

front of, that law enforcement gets in front of any potential violence and acts on it.

As we move forward towards the next series of election cycles and the rhetoric continues into 2022, 2024, the possibility of additional attacks,

I don’t even think it’s — I don’t think a possibility. I think it’s very likely to happen. It will.

SREENIVASAN: Retired Special Agent Tom O’Connor, thanks so much for joining us.

O’CONNOR: Thank you very much, I appreciate the opportunity to talk to you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Crisis in America. And finally, tomorrow we will continue to examine the crisis here, women’s rights under Taliban rule, with a longtime

activist and former peace negotiator, Fatima Gailani. She was one of four women who sat across from the Taliban during the Doha peace talks back in

2020. We assess the reality for tens of millions of women who have no choice but to stay and navigate this new Afghanistan.

That is it for now. Thank you for watching and goodbye from Kabul.