Read Transcript EXPAND

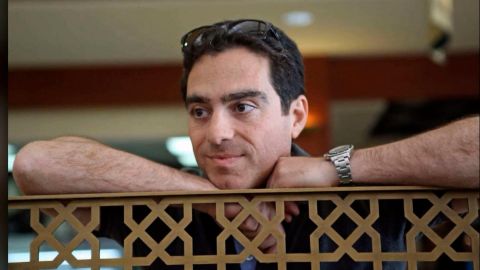

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR, CHIEF INTERNATIONAL ANCHOR: Now, as U.S. tensions with countries like Iran grow, our next guest warns that the world could be entering an era of “great power conflict.” One that could see the United States face off with China and Russia. It is a conflict that he says the U.S. is not yet ready for. The Wall Street Journal’s national security correspondent, Michael R. Gordon, has been reporting on the United States military for decades. And he tells Walter Isaacson that America has to come up with new ways of waging war.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON, HOST: Thank, you Christiane. And Michael Gordon, welcome to the show.

MICHAEL R. GORDON, NATIONAL SECURITY CORRESPONDENT, THE WALL STREET JOURNAL: Glad to be here.

ISAACSON: You have this amazing piece in “The Wall Street Journal” about how the era of great power competition is reemerging. I mean, we went through that in the Cold War and then, after, you know, 1989 we thought it was receding (ph) with Russia. And then, 9/11 made it that we are fighting insurgency. Tell me what you mean about the rise of the superpower confrontations.

GORDON: Well, this, in fact, is the main business of the Pentagon and has it been really since 2018. And following the American wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and to a certain degree in Syria, against ISIS, there was a stock taking at the Pentagon and a reevaluation of what the next missions would be. And it was a determined that the Pentagon really needed to gear up for what they called, at the time, a world of great power competition, which was a thin euphemism for China and Russia. And that was a strategy that was promulgated by then Defense Secretary Jim Mattis, but the Biden administration has doubled down on it in its own version of the strategy, which he had issued last year.

ISAACSON: And so, does that mean we change the way we procure weapons and do a lot of things with a focus on the fact that we may be fighting Russia and China now in insurgency wars?

GORDON: It requires a very substantial transformation of American defense in terms of where we put our forces, the kind of military technologies and weapons that the U.S. buys, the very structure of some of the armed forces has to be rethought. They have to find a way to connect them all up so that they can share targeting information in real-time. Because the task of deterring China, which is the primary threat, according to the Biden administration’s Pentagon, is just an enormous undertaking where you are dealing with a potential adversary, really, that has the homecourt advantage with Taiwan just 100 miles from the coastline of China.

ISAACSON: If you agreed, you know, and you’re a great military historian, but you go back to Thucydides and obviously, Bismarck and Metternich, you talk about great power competition. But the real warning they always have is never get into a great power competition with two different great power adversaries, especially when you are pushing them closer to each other. Aren’t we making that mistake with Russia and China, moving them closer to each other as we become adversaries to both?

GORDON: No, they’ve moved themselves closer to each other. I don’t think you could fault the United States for that. I mean, what’s happened is we just have to deal with the world as it is, not as we would like it to be. And in this world, China has been — its military might has been growing substantially. It has a strategy of trying to coerce Taiwan politically to rejoin China and to extend its jurisdiction over that. At the same time, Vladimir Putin has his own agenda, which we’ve seen play out in Ukraine, to kind of push back NATO. And these two countries have found common cause with each other against the United States. I don’t know that you could call it a formal alliance, but they clearly see benefit in cooperating to a certain degree in their kind of broader project to diminish American influence around the world. So, this is an enormously challenging thing for the Pentagon because it has to be prepared to both deter conflict in the Western, Pacific, thousands of miles away from the United States, and simultaneously deter conflict in Eastern Europe, halfway around the globe. And what makes it even more complicated is that China and Russia both study how the United States went to war in Desert Storm against Iraq, and they’ve devised novel strategies and tactics to try to frustrate the U.S.

ISAACSON: You’ve written a book recently called “Degrade and Destroy,” which is about the campaign against ISIS that we are fighting. The book comes out in paperback soon. Tell me what lessons we learned from these insurgency wars or maybe bad lessons we learned that apply today?

GORDON: We had advantages in fighting ISIS and in fighting Al Qaeda and even fighting the Taliban in Afghanistan that we don’t enjoy against China. For example, in those conflicts, we had totally unrivaled, uncontested air supremacy. These insurgent and militant forces didn’t have an air force, they didn’t really have affective surface to air capabilities. So, we had air dominance. None of that would apply in a war with China. Second of all, we had bases throughout the region from which we could project power, ground power, air, power and the like. And these bases were largely immune from enemy attacks, that also wouldn’t be the case in a conflict with China. They’d go after our bases in Japan and Guam, from the get-go. So, the war against ISIS is a very similar. But there are some lessons, which is it in the war against ISIS we relied extensively on the Iraqi military, on Syrian forces to be the grand element. We didn’t put a lot of American forces in combat. There were some, but not a lot. So, we let them do the main fighting. I think that’s the way of the future for wars in the Middle East. Why is that? Because our main focus is going to be on China and Russia, and if we are going to have to tangle with militant forces in the Middle East, at least we’re going to want to rely heavily on partners on the ground instead of our own troops. One exception would be if there is ever a war with Iran. But I think that one of the lessons is the war against ISIS showed how we need to fight in the Middle East if we are going to put most of our effort into deterring China and Russia.

ISAACSON: Are we inevitable conflict with China?

GORDON: Well, it’s hard to foretell what’s going to happen in the American relationship with China. But in the case of China, their project to extend their influence and control over Taiwan is at variance with the American posture and the Western Pacific, which is to defend free trade, to protect allies like Japan in the region, whose security would be greatly compromised if the Chinese were in control of Taiwan.

ISAACSON: And do you think that President Biden has taken that a bit further, the defense of the Taiwan situation?

GORDON: He is taking it a lot further, because the policy — the official policy is still one of strategic ambiguity. And what is the policy? We provide arms and weapons to Taiwan. We provide a limited number of trainers. “The Wall Street Journal” recently had a story and how that was going to be expanded, but it is really a small number. We are trying to give Taiwan the capability to defend itself against China in order to deter China from ever forcefully trying to take over that island. Where the ambiguity comes in is the U.S. is left unclear whether we’d employ its own forces to come to Taiwan’s aid. Now, what President Biden has said on more than one occasion is that the U.S. would. And the Pentagon, in fact, is planning to do so not because a decision to do so has been made, but because you have to have the plans and the capabilities in hands, in advance, in case your called on to do so. Now, one thing that’s important to recognize is the Pentagon doesn’t think that China can take Taiwan today. It would be an enormously challenging task for China. They have to do an amphibious landing, which they’ve never really done. They would have to — China forces haven’t fought with the Americans, really, since the Korean War. So, it would be — it’s highly ambitious. And in, fact according to the CIA, the current Chinese military leadership is not confident it could carry out such an operation today. But Xi Jinping has instructed his own forces to be ready to do so in 2027, according to the CIA. That does not mean they would do so, but it means that he wants to have at least that option, and a minimum for political coercion, and perhaps more than that. So, what is going on now is there is a race. There’s a race between the Chinese to get ready to develop this option and there is a race by the Pentagon to develop the capability to counter the option so the Chinese don’t employ it. And in this race, we are trying to develop new capabilities and deploy additional forces. And many of these programs won’t come to fruition until the 2030s. So, the next five years are a pretty anxious period for that part of the world.

ISAACSON: You wrote in your piece about war games, you know, that we play sometimes, and you can explain what a war game is, but it’s something the Pentagon does. Tell me about the war games that’s been happening on the concept of a struggle in Taiwan.

GORDON: Well, the Pentagon does highly classified wargames or simulations. They’re all done in kind of computer simulations and conference rooms and in military bases. And in the — my recent article, I recount one that was in 2018, and there is an air force general, it’s Lieutenant General Clint Hinote. And he had recently been assigned from the Middle East to come back to the Pentagon and be one of the people planning the future of the air force. In fact, today, he is in charge of that task, these air force features is what the officers called. And he comes back he told me all on the record that, you know, he’s — when he first saw the results of the war game of how he would fare in a conflict with China, he’s — the expression he used was holy crap, you know. We’re going to lose if we fight like that.

ISAACSON: So, what went wrong? What were we missing?

GORDON: Unlike the conflict in the Middle East if you assume that we’re at war with China, our air bases in Japan are going to come under missile attack almost immediately. Our naval base in Guam is going to come under attack immediately. This is going to interfere with our ability to replenish subs at seas, and subs are really important. Our ability to supply our own troops with logistics is going to come under fire, there is a terminology for this in the Pentagon, they call it contested logistics. None of that was true in our wars in the Middle East. Those — we assemble forces over a period of six months. If you remember the Gulf War, you know, no one interfered with that. We pick a time on we want to initiate the conflict. And then, we did without any appearance. Well, that wouldn’t hold in a war with China. So, what the General Hinote was pointing to was that these assumptions with regard — guided the U.S. employment of force in previous conflicts would no longer obtained. Therefore, you need a totally new concept for how to do this. You need to have some forces that could survive within range of the Chinese missiles. That’s what the marines are trying to do now. You have to have additional standoff capabilities, long-range missiles that you could fire from a safe distance into there. You have to integrate these capabilities and novel ways. So, it’s not merely a matter of shifting our current military to another part of the world, it’s a matter of coming up with what the Pentagon calls new operational concepts, new forces and new ways of employing the forces to deal with the threat that’s entirely different from the one that we’ve been involved with for the past few decades. And then, you have to factor into this the possibility that, if Russia and China are not formal allies, if were caught up in a conflict in the Western Pacific, Russia might act opportunistically to pursue some aims in, let’s say, Eastern Europe. And we know the Russians have had a hard going in Ukraine, but you still haven’t prepared for the contingency that, let’s say, a decade or two from now, they might strike out somewhere else, thinking we were bogged down in the Western Pacific. So, it is really a very formidable challenge.

ISAACSON: Well, you talk about one of the battles coming up, which is the budget battle. And that’s really beginning this week and next week. And so many times over the past decade, the budget battles have caused us to spend more, in some ways, on weapons, even as we try to spend less. We spend as much as the next nine militaries combined and yet, we don’t get a whole lot of bang for the buck. What do you think is the problems we are facing with our budgeting strategy?

GORDON: Well, I do think we get a lot of bang for the buck. And I feel that the idea of comparing American spending to other countries is just a little misleading. Because, first of all, we have a professional military that pays a lot more than Chinese military pays. Personal costs eat up a lot, as does health care. Also, the United States has global responsibilities. They’re trying to deter Chinese aggression and Russian aggression in totally disparate parts of the world. There’s no other country that has that as a mission. So, to compare our budget with countries that have niche capabilities and limited responsibilities, I don’t think is directly relevant. The Congress is sometimes been helpful to the Pentagon. I mean, here’s an example. They’ve added money to the Pentagon budget in recent years primarily because of their concern over the China threat. So, when the — last year, when the Pentagon proposed research and development budget of $130 billion, that’s an enormous amount of money, it would be the highest R&D budgets in Pentagon history. Well, the Congress added 10 billion to that, saying, well, we got to do more on hypersonics and other technologies.

ISAACSON: The Biden administration has put $25 billion, I think, in weaponry into the Ukraine conflict. Tell me how that’s affected this strategy in our military readiness?

GORDON: Well, I don’t think it’s affected our military readiness in a bad way. I may have a slightly iconoclastic view on this. Certainly, spent a lot of resources in Ukraine. But a lot of the weapons, number one, we are giving Ukraine from drawdowns from our own stocks, 155, artillery, shelves, javelins, things of that sort. I mean, those are not the kinds of weapons U.S. military is going to use in a war with China. We are not fighting a land war with China. We’d be operating with, you know, long-range anti-ship missiles or marine forces, you know, and anti-ship missiles and the like. Hypersonic missiles. We’re not going to be fighting trench warfare with the Chinese. So, some of these weapons that are being provided to Ukraine are not relevant for a U.S. fight with. China. The second point I would make is, you know, the Russians have lost more than 1,000 tanks. They’ve lost a substantial part of their armed forces. They’ve had more than 100,000 killed and wounded. Their military capability has been diminished significantly. That’s a positive thing from the U.S. perspective. So, yes, we’ve given Ukraine a lot of weapons but they’ve been used to diminish Russia’s military capability, at least, conventional military capabilities to have enormous nuclear capability for, you know, a period of time. So, that is a net plus from a U.S. strategic standpoint. But here’s the problem for the U.S. What the Ukraine war has shown is that in conventional conflict, weapons can be consumed at enormous rates. I think much more than the West anticipated. So — and there is a problem with the American defense industrial base, and just keeping the weapons flowing. I mean, it’s not enough to have small numbers of these things, you have to have massive numbers of these things to keep up the volume of fires. So, one of the hurdles to implementing the new strategy is to revamp the defense industrial base. I mean, take submarines, we’re producing about 1.5 attack submarines a year. There’s a deficit of submarines. Submarines are important in the Western Pacific. That’s not a problem that’s easy to quickly remedy. It is a product of concluding that the Cold War was over and spiking the ball in the end zone a little too soon. So, these are sort of the bigger challenges that have to be met, if you are really going to make this strategy real. It’s one thing to announce the new strategy. The Trump administration did that. And so now has the Biden administrations. That’s the easy part. The hard part is implementing the strategy and doing so consistently over a period of a decade and longer.

ISAACSON: Michael Gordon, thank you so much for joining us.

GORDON: Thank you very much for the opportunity.

About This Episode EXPAND

Iranian-American businessman Siamak Namazi has been imprisoned in Iran’s notorious Evin Prison for seven years. In an exclusive interview, he tells Christiane that he desperately needs President Biden’s help. Vali Nasr, a former senior adviser at the U.S. State Department, discusses U.S.-Iran relations. Journalist Michael R. Gordon says the world could be entering an era of “great power” conflict.

LEARN MORE