Read Transcript EXPAND

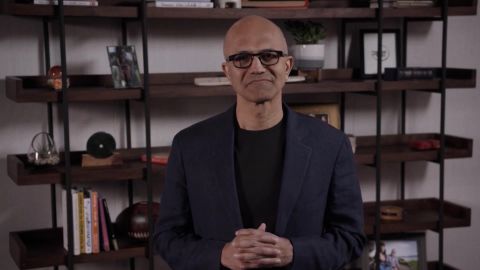

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And now, today, the annual Microsoft global conference begins. And like most gatherings at the moment, it will be conducted digitally for the very first time ever. Satya Nadella is the company’s third CEO. He has drawn praise for transforming Microsoft and for his unique leadership style, which is rooted empathy, something he says that he learned while growing up in India, and then while raising his own son, who has cerebral palsy. Walter Isaacson has been speaking and is talking to Nadella about how the tech world is innovating in this new reality. Here’s their conversation.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Satya Nadella, welcome to the show.

SATYA NADELLA, CEO, MICROSOFT: Thank you so much, Walter.

ISAACSON: How has this coronavirus pandemic affected what Microsoft is thinking of doing in terms of products and services?

NADELLA: You know, first of all, Walter, this is just the most unprecedented situation, crisis that we, as a world, have seen. And so I would say the first thing that we ever have to do is to ensure that our own employees are safe. And so we took immediate action as we saw this spread around the world to help our own employees go home and work from home and stay safe. So, the protocols that we had to implement there were definitely possible because of our products. But the other thing that we have also had to do is to be the digital first responders to all the first responders out there. When you think about the health care workers, everything from how they’re able to deliver care, how their supply chains are working, Microsoft has had to lean in, whether it’s with the CDC or with Providence Healthcare here and hospitals around the globe, and helping them. Same thing with education. We are in that phase where we are now talking about the response phase, but there is going to be a recovery phase, and then there is going to be a reimagined phase. And there, again, we will have to rethink what technology can do.

ISAACSON: When we get into that reimagined phase, what does that mean in terms of the way we’re going to organize our work forces?

NADELLA: To me, the real reimagination, I think, at least from a digital technology perspective, will come when three secular forces are used to accommodate the flexibility that our society and economy needs. And I, for one, Walter, take away that what the world needs is more flexibility. It’s not about one dogma going to another dogma, but resilience is fundamentally built on flexibility. And I think, given software is a malleable resource, the first thing I think we can do is, really, this ability to separate out the control plane from the usage plane, right? So, when you can have the manufacturing happen remotely — that is, the control of manufacturing plant — the physical plant remains, but the manufacturing control is remote. Or when you can have an A.I. bot triage a patient’s symptoms and then have a talent medicine workflow, before you have to have whether a test get coming to you or whether you have to go to a hospital, that type of flexibility around remoting. How do you simulate? Now, here is an another fascinating thing we learned. Simulation is such an important thing. Take even how the immune system responds to a virus, or how do you really simulate a manufacturing run using, again, simulation software and automation?

ISAACSON: All that makes a whole lot of sense. But I know you pretty well. You have empathy at the core of your being, both from your childhood, your family and your employees. Aren’t you missing something when you can’t be there personally with people?

NADELLA: No, absolutely. I mean, I’m glad you brought that up, because one of the things that while — for example, even in Microsoft, if you look at some of the statistics around, let’s say, developer productivity — after all, we have a lot of software developers. One statistic we look at all the time is, how is code being written? Is the code of good quality? Are people able to collaborate, in a sense, even to produce the code and the innovation? Some of those things statistics look great. But one of the fundamental things that I worry about and I want us to study more deeply before we claim that everything is fine, even in remote work, is the point you make, which is, what about that human connection? After all, when I look back at my own self, right, whenever I used to walk into a meeting, in the hallway, I would meet two or three people, talk to them, learn from them, connect, build social capital, talking to the person next to my meeting, before the meeting, after the meeting. All that had a real impact on my outlook, how I approach work, what I learned. I feel sometimes now we’re taking all that social capital we have built up and are burning it a bit, while we are staying productive remotely. And that’s good, but is it a long-term solution? I don’t know. I think this is one of those places where we need to stay a little humble. To your point, we have to ultimately look at what that — it’s not just about productivity. It’s about the well-being of people and our society.

ISAACSON: Is it possible to try to recreate the physical experience of being together and blend it in with doing it remotely, so that our colleges can reopen with people on the campus, our schools can reopen, even Microsoft headquarters can do it, and yet you somehow use the software to keep us safer?

NADELLA: Right. In fact, we’re thinking through a lot in this back to work or — back to work place, because, after all, people are working. And so, today, the question is, what does it mean to go back to your office space? And how do we do it? We are definitely, at Microsoft, not all going to go back to work at once. And we’re not even going to be the first, because we have, I would say, the privilege of the ability to work remotely. And so before we come back, a lot of the other economy is opened up and they’re coming back to work. We, in fact, are working with the UnitedHealth Group to even come up with some software to help businesses, for example, starting with self- attestation, right, because the key priority is, how do you keep people safe? And it starts with people being able to self-report their symptoms and if they or — they are vulnerable or they’re not healthy and or people in their home or not, are vulnerable, it’s best for them to work remotely. So, I think what we’re going to create is a very flexible, hybrid way for people to come back to the workplace.

ISAACSON: That sounds good for people like you, me, people who work at Microsoft, people who can do things remotely and online. But there’s so many workers that are having to go back who have to be there physically, who have to be in the meatpacking plants or make deliveries or work on the docks behind me to unload the grain, those type of things. Are you worried that this notion of going to a more digital, remote type work force exacerbates the great divide between people who have to show up and make products vs. those who can work remotely?

NADELLA: No, it’s a great question, observation, and a real issue, because, as I have worked with many of our partners and customers, they remind me that they are sending millions of employees to work, so that a lot of us we have the privilege to be able to work from home can work from home, as you rightfully said. Critical services are happening because people are working, delivering, driving. Grocery chains to hospitals are a great example of that. And, to me, I think what we have to do, as a society, everything to ensure that we value this. I think, coming out of this, Walter, that’s the other piece that I think we’re all going to learn, is, is the value we ascribe to all type of work right? Or does it have to change? When you sort of realize that 20 percent of your GDP have to be spent in order to recover from the impact of this pandemic, I think we are all going to probably go back to the fundamentals and ask ourselves, what could we have done to have avoided this situation? I think we would have started with, what does it mean for us to really take the work that organizations like CDC or what epidemiologists do, what is real — what is what basically monitoring of any pandemic-like situation look like, funding for it? So I think, to your point, we will have to sort of really think about wage support, as well as real, at a societal level, valuing all of the activity, not just the activity we thought was the most productive, because I think the most productive activity we sort of ascribe value to is very dependent on a lot of other activity in our society.

ISAACSON: You have the Build conference coming up. I was wondering if there’s anything emerging from that, new ideas, new ways to do software development conferences.

NADELLA: Yes, I mean, it’s pretty exciting. First of all, I would say one of the things that I am — if there is a silver lining in all of this, is how the current architectural software, which is the public cloud software, some of the A.I. breakthroughs, are all — and even the collaboration software, like Teams, have been so helpful in this business continuity and response phase. I shudder to think even if this was 10 years ago what level of economic activity and productivity could we as a society have even maintained? So, I would say, thanks to all the software developers, that has been fantastic to see. I think, going forward, what we are in fact going to talk at Build is, what does that remote everything look like, right? For example, if you have cloud computing power now both in the cloud, as well as at the edge with 5G, where — low-latency compute, what would the hospital look like? How could contactless e-commerce happen? What does curbside pickup look like? So, we can reimagine so much of what one needs going forward in an economy that is adjusting to these new realities of maintaining social distance, maintaining flexibility and how work happens. I think that’s one place where I think software developers have both a tremendous opportunity and a tremendous responsibility.

ISAACSON: What about software services built on your platform in which people can test themselves, they can get a clear pass, so to speak, in order to go to work, they can be tracked and traced? What type of things like that do you think will be coming out soon? And will people kind of freak out about the privacy?

NADELLA: First of all, the UHG app that’s going to — is being rolled out on our infrastructure provides some of that service. And…

ISAACSON: That’s the UnitedHealth Group, right?

NADELLA: That’s correct. The UnitedHealth’s application. And, of course, they’re in the health care business. They understand this deeply. They already use this for their own first-line workers in the health care sector, as well as inpatients. And now they’re making it available even to large employers. And the key principle they have is that it’s all going to be done within the context of health care data and health care data regulation. So, for example, all of the health record information would be protected under the existing laws of health care privacy. And what now businesses can do is just get that self-attestation, essentially, about the status. It’s just like vaccine reports we may have used in the past, when we are going to school or to other countries. That’s the level of sort of, I would say, demarcation between the two data sets. One is, how can you use your health record in order for you to be able to then make sure you are safe, and then you’re keeping others safe? And that’s the workflow that the UnitedHealthcare Group is going to produce.

ISAACSON: As a kid growing up in India, you loved cricket. And one of the things you have said you have learned from cricket is the need for teamwork, for collaboration, for just knowing where everybody else is on the field and playing together. Are you worried that we’re going to lose that in our K-12 education, in our lower schools and middle schools, where most of what people learn, kids learn there, is how to play together and how to work together? Is there some way we can help save that as we go towards more remote education?

NADELLA: I mean, it’s, I think, one of the questions that needs to be sort of really answered by even people who are experts in how learning happens, right? For example, when we think about learning, there is the — how do you have attention? How do you have active engagement? How do you have many of these things that — and teamwork? These are all very important for learning to thrive? So we have to come up with mechanism. But there are some things. Like, take Minecraft. Even prior to this pandemic, Minecraft would become the tool where kids could come together to collaborate, learn to build together. In fact, it became a fantastic tool for young middle school girls to get introduced to STEM education, because it was an open world vs. the classic C.S. curriculum. So, I think we will come up with breakthroughs like that. One of the other tools that has really seen a lot of usage growth in the — during the pandemic is a tool called Flipgrid. I don’t know if you have seen this. This is a tool. It’s sort of used for submitting short video clips as homework, and people collaborate on that — those projects. So I think that we will come up with some tools. But, ultimately, Walter, to your question, there is no substitute to that inspired student and that inspiring teacher, because no amount of technology can be a substitute for, ultimately, I think what the educational system needs, which is students, teachers, administrators, parents, and the community coming together, using perhaps new mechanisms, new tools. But we have to prioritize that this is important.

ISAACSON: One of the key things you have emphasized as a leader is empathy. Tell me about what you learned from your son, who has cerebral palsy, and dealing with that situation.

NADELLA: I mean, to me, I think the word empathy essentially is what is innate, I think, in all of us as humans. It’s the life’s experiences that teach us how to relate, connect, understand where others are coming from. You — it’s — in fact, from a business context, I believe that empathy is at the core of design thinking, right? When you say we want to meet unmet unarticulated needs or customers, it comes because of a deep source of empathy. But the reality is, you can’t go to work and say, let me turn on the empathy button. You have to learn from your own life’s experience. And, in my case, definitely, what I have had to — I have learned a lot from my own son’s experience. In fact, I have learned a lot watching whether it’s my wife and what she did in the formative years to care for him, give him every opportunity, all the care providers, the speech therapists, the occupational therapists, the degree of empathy they had for my son’s situation and how they really helped him. That’s influenced me, influenced me as a human being, influenced me as a leader and a manager. And I think that that’s sort of what I think we all bring to work, because each of us learns from our life. Each of us each day know how to relate more to more people and understand them more deeply. And how do we take that understanding then to have the impact is what at least is what I feel innovation is all about.

ISAACSON: How often do you talk to the co-founder of your company, Bill Gates, who has been deeply involved in this? And what do you all talk about? What have you learned from him?

NADELLA: Right now, of course, Bill’s spending all his time even on the pandemic response. And it’s amazing to see what he and his foundation, him and Melinda, are all doing. And we’re very thankful for that work. And, now, I’m very connected to Bill, both on the health care side — so I go to him, after all, with his expertise. There’s no better person to go to when we’re thinking about back to work or how should we show up as a good global citizen in the world? So, Bill’s well-connected with the company. He doesn’t have a formal role, because he decided that it’s time for him to spend more time on what he’s doing, which we’re all thankful for, around his philanthropy and his foundation. But he will always be connected to Microsoft. After all, it’s the company that he founded and definitely what he stood for in terms of excellence in really having both high ambition and a high bar for execution. To meet those ambitions is something that will always be inspiring for us.

ISAACSON: Satya Nadella, thank you so much for joining us this evening. Stay well.

NADELLA: Thank you so much, Walter. You too.

About This Episode EXPAND

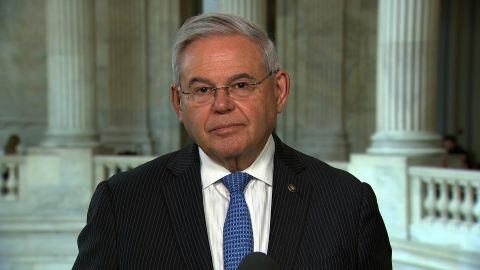

Senator Bob Menendez reacts to the White House’s firing of State Department Inspector General Steve Linick. Veteran journalists Susan Glasser and Ed Luce discuss the wider political fallout of Linick’s dismissal. Navajo Nation president Jonathan Nez explains the toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on his community. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella discusses how the pandemic is pushing tech innovation.

LEARN MORE