Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: The struggle is, sometimes we eat, sometimes we don’t.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: In the United States and around the world, coronavirus forces tens of millions more into poverty. Economist, Mariana Mazzucato, tells me

why we must fix capitalism and not just go back to normal.

Then —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

MICHAEL PALIN, ACTOR AND COMEDIAN: I can bring a picture from a country that comforts me and interests me and excites me at almost any time.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Around the world in 80 days? Not possible in a pandemic. So, I reminisce with a national treasure. Yes, Monty Python cult hero, Michael

Palin, joins me.

Plus —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

JOEL C. HUNTER, CO-FOUNDER, “PRO-LIFE EVANGELICALS FOR BIDEN”: Opposite of the gospel, it is me first, our country first, America first. Nobody else

counts as much as we do.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Breaking with the base. Why some evangelicals are turning away from the president.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

Amid a second COVID wave and plunging economies, it’s important to remember that behind every statistic lies a human being, a person. Just as the U.S.

approaches 8 million coronavirus cases, another 8 million people slip into poverty. That is since May according to Columbia University. 1 million

people have died around the world. More than 38 million people are infected. And the Gates Foundation reports the pandemic has pushed another

37 million people into extreme poverty. That means living on less than $1.90 per day.

By the way, the rich are still getting richer. Much, much richer, in fact. And as the United States and Europe struggle with how to relieve this human

suffering, it’s going to get worse with new lockdowns and restrictions on the way.

We’ll delve into all these shocking statistics with our first guest tonight. She is the economist and professor, Mariana Mazzucato, also author

of “The Value of Everything,” and she says it will take a complete overhaul of capitalism as we know it to right this ship.

Mariana Mazzucato, welcome back to the program.

Those statistics are really horrendous and you’ve seen all these rolling new instructions from various governments, certainly around Europe, of

lockdowns and curfews and tiers. And it’s causing a lot of backlash on the ground. What do you — how do you assess the situation right now?

MARIANA MAZZUCATO, PROFESSOR IN THE ECONOMICS OF INNOVATION, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF LONDON: So, I’m not a medic. So, I just talk about the

economic, you know, situation. And I think, you know, unfortunately, with the lockdown, if it happens, it happens. But the real question is how do we

structure it?

You know, there is different way to structure about the recovery funds that are going to be needed, even more now with lots of businesses probably

again having to close, if we think of the hospitality sector. But the question is, can we, even in the structure of those recovery funds, or also

how workers are going to, you know, probably need, again, for a longer period to have a furlough scheme, how can we actually structure that so it

really does “build back better?” And I think there, we need to really study what’s happened in the last six months.

There’s been, you know, real heterogeneity differences in how governments have responded. And those that have also turned this crisis into an

opportunity, and I know that sometimes sounds strange, but an opportunity for really turning their economy into a stronger one, a more resilient one,

we need to learn those lessons. And it’s really interesting how some of these countries were developing countries. So, both Vietnam and for

example, Kerala in the state — sorry, in India, both have been investing over the last decade or so inside their public sector. They haven’t been

doing, for example, what’s happened here in the U.K. where I’m standing, sitting, which is kind of outsource that public sector capacity, including

the testing that’s being outsourced right now to the consulting companies.

So, when you strengthen your public system, you can govern a crisis better. And so, there’s lots of lessons like that, including also coming back to

the recovery scheme issue. In France, Macron was very clear. He said, you know, yes, we will help business, but we won’t do it just as a handout. We

have to build back better. So, he put really strong conditions on the car company, Renault, and Air France to actually lower their carbon emissions.

And that shouldn’t be seen as a penalty. It’s really an incentive to innovate and to invest in this very difficult period so that later, once we

have a proper recovery, we have actually a more sustainable economy.

AMANPOUR: So, that’s really encouraging to hear, because the stats are really quite tragic right now, if you talk about individual people and I

reeled off the millions of people who have been plunged into poverty. Vietnam is a miracle that we should — at least that’s what it’s being

called — that we should actually be discussing and Kerala really interesting and what you said about the conditions for a lot of these

loans, as you said, with Macron.

But here in the U.K., for instance, this triple tiered system, you can see the leaders, the elected leaders of the region, like right now up in

Manchester and elsewhere, they are just — they’re on the brink of refusing the orders from the central government here in London. And I just want to

read you what — or play you what a very prominent British dame in the House of Lords said today about what the people are going to be left with

if they just get a part of their salaries paid. This is what she said. It was quite shocking.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

LOUISE CASEY, FORMER U.K. GOVERNMENT ADVISER ON HOMELESSNESS: Do we want to go back to the days where people can’t put shoes on their children’s

feet? You know, this is what we are talking about. Are we actually asking people in places like Liverpool to go out and prostitute themselves so that

actually they can put food on the table?

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, that is Dickensian. I mean, that is really raising a very, very tragic and ugly specter. She used to be a government adviser. She’s

advised this one before. She’s been working on poverty issues for decades. And she says she’s never seen anything like this. This is Britain.

MAZZUCATO: But she’s right. She’s absolutely right. And unfortunately, that was also Britain before this crisis. You know, the level of inequality

in this developed economy is very high. As it is in the United States. And so, the problem is that when you have a crisis like this, unless it’s

managed properly, then those who are most vulnerable, who were already vulnerable, lose off, you know, incredibly.

You were talking before about the companies that are actually, you know, making billions off of this crisis because we’re all on Amazon more than

ever, we’re all in Netflix more than ever when we can’t go outside. Those companies are doing fine. But those who’ve actually worked in the gig

economy, who don’t have benefits, who don’t even pre-COVID have benefits, whether it’s holiday pay or pensions, they are suffering incredibly right

now as do those who were unemployed.

And so, there’s nothing inevitable about suffering. It depends how we actually structure our economic system. When we go to war, we somehow just

find money, right, to fight the war. No one says there’s no tax revenue, we can’t go to Afghanistan. So, we really have to treat this with the same

level of urgency, emergency, empathy, solidarity, as we do in a wartime. And I don’t like to, you know, say that we have to think of it as war, but

we really need to think of it as a security issue in the same way that Greta Thunberg said that, you know, if your house was burning down, you

wouldn’t debate what to do, you would get out. And she said that about climate change. Treat it as an emergency. Listen to the science. That’s

exactly what we have to do right now.

And believe me, there’s lots of scientists who have been both warning about what we should have been doing in the last six months but also how to steer

the next six months in such a way that actually creates certainty. The problem right now in the U.K. is that you have these different regions that

are — it’s almost like a, you know, race to the bottom. Like, if you don’t have a national plan and a national level of really seeing, you know, all

the different regions and how to make sure that it’s not about asking the mayors or the regional, you know, administrators to pick up the pieces,

we’re already hearing this, by the way.

After the very generous recovery fund in the U.K., very soon, we started hearing about burden sharing. And burden sharing means really that the

local councils, for example, will have to make cuts eventually. That makes no sense. You know, the one thing that this pandemic has taught us, that

health systems really matter, global health systems matter. We are only as safe as our neighbor is, on our street and our city and our country and

internationally.

So, had this crisis begun in a country that had a weaker health system, for example, than China’s, we would all globally be worse off. So, the last

thing you want is to be asking local administrations to start cutting in order to share the burden of the extra funds that the government unleashed

rightly so in the emergency. And so, this is what we really need to keep our eye on.

AMANPOUR: So, I’m going to ask you in a second, you know, how — what you would advise for these next six months since the first sixth months were

kind of wasted in terms of economic activity. And particularly, as you remember, everybody was saying, oh, it’s going to be a V-shaped recovery.

It’s going to go down, then it’s going to up. But actually, it’s K-shaped, which apparently, for you economist know better than me, means frankly the

rich people go up and the poor people go down. That apparently is the summing up of a K-shaped recovery which we’re seeing now.

The World Food Programme, he just got the Nobel Peace Prize, right, for combatting hunger. David Beasley, who is a former government of South

Carolina, I need an additional $5 billion, folks, right now to save 30 million people. Just $5 billion. It may sound like a lot to a lot of

people, but UBS has said that the super-rich have increased their take to $10.2 trillion under this COVID. That’s 27.5 percent increase in their

pockets. So, who — who’s incentivized to help and what should, for instance, a government here do, let’s say?

MAZZUCATO: Well, again, I mean, I really think it’s important to owe a start with what we were seeing before this crisis. We already had taxation

around the world that was regressive, that wasn’t really re-distributional. We had too much tax evasion and avoidance, which, you know, by a lot of

these companies that are doing very well right now which then hurts the public purse, it hurts the public purse that’s required for public

education, public transport, public health.

So, all these problems were already there. In a crisis, the problem escalates, as we were just saying. Those who were most vulnerable before

and who were losing out lose out even more now. And so, what we absolutely need to do is to make our economies as re-distributional as we can in the

first instance. So, help those most needy, as Pope Francis said. He talks about that we need to always, you know, be thinking how policies are

affecting the poor and to, you know, use that as a guiding device. And whether one is religious or not, it makes a lot of sense, but that actually

means doing things very, very differently.

And, you know, this is why we need to talk about how we are recovering right now, today, over the next months, if there are more furlough schemes,

for example, that are necessary so governments can help in the U.K. but also elsewhere, companies continue to pay their worker’s wages, at least

those lucky enough to have a job. That — it’s all should be conditional that as soon as those furloughs are up, those workers aren’t just

immediately fired, right? There’s all sorts of ways that you can structure within, the bailouts, the different types of recovery plans, ways to make

sure that this is sustainable, that actually makes our economy more resilient.

AMANPOUR: OK. So, Mariana, why aren’t they doing it, then? Why aren’t they doing it? You know, there seems to be a global allergy to deficits and

people say, oh, well, if you do all this spending, we’re just going to go back to austerity like we did in the mid-2008. But I’m hearing the IMF

saying spend, spend, spend, just keep the receipts. Other economists are saying, you may be one of them, you know, just spend. I mean, you know, put

the money into the system. Why is that OK now when deficits were, you know, the bug-a-boo just a few years ago?

MAZZUCATO: So, I mean, I’ve been saying to invest for a long time. But the question is, how do you invest, right? So, the obsession with the deficit

was always ill-placed. It made very little sense. Again, I’m from Italy, or I didn’t tell you that, I am from Italy, and, you know, there was a lot of

obsession about reducing Italy’s deficit after the financial crisis. All we needed to do was look at Italy’s numbers, the definite was never that high.

The debt to GDP was high. Why? Because it wasn’t growing. Productivity wasn’t growing. So, the denominator to GPD wasn’t growing.

To get long-term growth and to get directed growth, to be more inclusive, so less than equality, to be more sustainable, more green, you need a

particular type of investment but you also need a particular type of public/private partnership that, you know, brings us back to the

conditionalities. However, I don’t think we should be too pessimistic.

So, in Europe — let’s ignore Brexit for a second. In Europe, the recovery scheme called Next Generation U, is quite generous and it’s conditional for

the first time, not like in the old days with the troika, cut, cut, cut, cut your deficit and we’ll give you some money. It’s actually conditional

on investment. So, all the different member states are having now, literally, as we speak, October, November, up until Christmas, having to

come up with strategies around digitalization, the digitalizing, the economy is reducing the digital divide, which by the way, has increased

massively under the COVID lockdown and around climate mitigation and health.

So that’s a positive news. That’s a big, big turn for the E.U., that these bailouts and the recovery funds, which total actually to _2 trillion, but

the Next Gen U extra pot is _800 billion is conditional on investment towards directed growth, inclusive, sustainable, et cetera. So, that’s

positive. Let’s talk about that. Let’s talk about, you know, how to make sure it actually works, right? Because you can have an E.U. plan, but then

if the member states actually are weak or if they have problematic, internal debates, you know, the country you and I are living in, even

though it’s not in the E.U., we can talk about how we’ve gotten so stuck in the Brexit debates. So, we didn’t have our eye on actually strengthening

the welfare state over the last six months or before, which, again, makes us more vulnerable when a crisis comes about. But, you know, different

countries have their own internal squabbles.

So, this is, again, a moment to say, look, there are these recovery packages, but they’re not going to be miracles. You used the word miracle

before when you were talking about Kerala and Vietnam. It’s not a miracle. It’s an outcome of the investments that they’ve been making. We need those

kinds of investments inside the public sector capacity, inside public health systems, we need recovery schemes like in Denmark which say, if you

use tax havens, sorry, you’re not going to get, you know, a public subsidy.

We need to restructure our economies that actually have an eye on what got us into this mess in the first place, both in terms of the financial

crisis, the climate crisis and the health crisis. We have a triple crisis.

AMANPOUR: So, really very quickly, because we’re running out of time. This is obviously urgent, right? I mean, you said some of it is good news, but

you’ve also talked about upcoming lockdowns to do with climate in the near future. So, this is an urgent operation that needs to be undertaken.

MAZZUCATO: Yes. I mean, let’s go back to this expression, it’s an opportunity. What you don’t want to do is to miss an opportunity, so later,

you are forced to do something that could have, if you actually planned towards it, made it an opportunity for investment, for innovation, for new

types of collaborations around all sorts of problems that COVID is confronting us with, from the digital divide, the weak health systems, to

the race for the vaccine.

The vaccine itself, by the way, we shouldn’t just call it a race. We need to govern it properly, so, you know, we don’t allow, for example, the

patent system to, you know, privatize each little bit of the way. So, that’s why the World Health Organization is calling for the patents to be

pulled to nurture collective intelligence. But this is the point that, you know, we have to act now, but we need to act in such a way that really does

build back better, and we need to learn how to do that in concrete ways which also require experimentation, and looking around the world, what can

we learn? What actually happened in Kerala and Vietnam? What’s happening in the U.K. that’s a problem? Why is it that actually allowing private equity

companies to run our care homes is a problem?

AMANPOUR: Right.

MAZZUCATO: Let’s talk about that, so we start doing that as opposed to finding ourselves in this constant reactive mode instead of a proactive

mode. And the climate lockdown expression that I wrote about in the project syndicate article was simply to say, with the climate, at least let’s not

get into ourselves where we have to one day stop, you know, everyone stop eating red meat, no one can drive a car. That’s not what we want to do. We

want to be in a position where we’re preparing our way to investing towards a more sustainable economy so we don’t then have to one day just

completely, you know, shut our current lifestyles.

AMANPOUR: Mariana Mazzucato, thank you so much, indeed, for joining us.

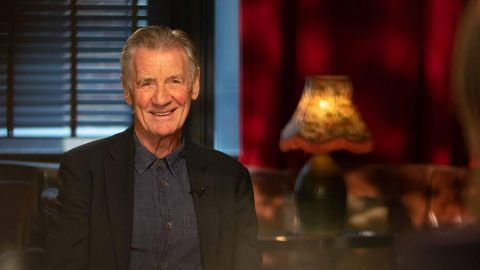

And now, for those of us who can afford to think of something other than this devastating hardship, we have a treat in store. My next guest is one

of the world’s most beloved adventurers, whose exploits on the road and in comedy, writing and acting have made him a global sensation. And along with

his band of brothers in “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” he’s been a cult hero for generations of fans since it took off in the ’70s. Michael Palin

is now 77 and in a reflective mood when we met up this week.

Michael Palin, welcome to the program.

MICHAEL PALIN, ACTOR AND COMEDIAN: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: I just want to ask, because, you know, you’re such now known for your travel, how has COVID been for you? What has lockdown meant for you?

PALIN: Well, it’s shut down my traveling time, but in a good way, because I’ve actually had time to look back on all the traveling I’ve done. The

last 30 years, I’ve been all over the place. And you know, you probably know yourself, it becomes a bit of a blur if you’re not careful. And it’s

really been quite nice to be at home. I have not left. I’ve not spent a night away from my house for a year. So, that’s it. Which is just unheard

of.

AMANPOUR: When you have looked back now in lockdown, what ones, if you can, you know, really, really sort of leap out at you? Which ones that

you’re looking back at do you say wow?

PALIN: Well, they were all remarkable. I mean, they really were. There wasn’t one easy one, they were — and there wasn’t one dull one. They were

all very extraordinary. Some days I feel I’d like to be up in the mountains, in the Himalayas or the Andes, which were just sensational.

Other times I’d rather be — you know, I remember going to the Philippines and learning how to scuba dive in about two days flat.

AMANPOUR: Let’s just go back to being just a little bit. Where did you first get the urge to perform, to make people laugh, when did you first

kind of know in your bones that this might be something you’re good at?

PALIN: I think it happens very early on. I mean, I always knew I was curious and wanted to go to places where other people say, well, I don’t

know. Let’s not go that far. But I wanted to go there. So, that was, I think, the traveling thing. I think it was also a feeling that I kind of

saw the world very often a little step back from my friends. I’ve enjoyed being teams of sport and all of that, but I was — I enjoyed looking at the

world from the outside. And I think that was part of the performing thing. I was able to, you know, mimic the masters at school, which is where a lot

of things happen. So, I made people laugh quite easily. I could just do a voice and this is wonderful.

I’ve always felt myself comfortable with being the observer, looking at the madness of the world that we’re all in.

AMANPOUR: I mean, I’ve read that your dad was a — you know, a bit sort of harsh, had a stammer, wasn’t particularly encouraging.

PALIN: Well, you know, my father, his stammer was, I think, the real problem throughout his life. And he never — he was never able to deal with

it. And so, that made him very, you know, techy and he would get, you know, quite sharp sometimes. But he had a sense of humor. And obviously, he loved

— you know, and having your son around. But my mom was really the great influence, if you like. She would just sort of feet on the ground, nothing

fazed her at all, despite all, you know, the things she had been through.

AMANPOUR: And she liked the idea that her young son was going to be an actor or a performer or a writer?

PALIN: Yes, she was happy with it. My father wasn’t at all. My father was deeply concerned that I might end up in the acting profession. So, he was

not keen for me to act. My mother on the other hand was very happy. I used to — when he was out of an evening, when I was quite young, I would read

her sort of chunks of Shakespeare of me playing all the parts. Can you imagine that? She had to be a wonderful mom to listen to all this going on.

AMANPOUR: And she was your audience? You’d do it for her?

PALIN: She was the audience, yes. Well, I think so. She may have nodded off a bit. But what I can remember later was when we did the “Monty

Python’s Life of Brian,” my mother was a keen churchgoer, but she defended absolutely our right to do “The Life of Brian.” Because I told her, it’s

not about Jesus. Jesus is not Brian. It’s about the church, it’s about some people just accepting what — doing what they’re told. And she would take

people on in that little place where she was living once she retired. She wouldn’t — you know, despite her religious background, she would say, no,

nothing’s wrong with this, it’s all about the intolerance of the church. And people would go, yes, Mrs. Palin.

AMANPOUR: That’s really amazing. Actually, it just led me right into a clip because somewhat around “The Life of Brian,” afterwards perhaps, you

and John Cleese had a television debate with an actual bishop and with Malcolm Muggeridge who was a commentator, a very famous British

commentator. They both were at your throat.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Would you imagine that your scene from Sermon of the Mount, the scene in this — in your film of the Sermon of the Mount is not

ridiculing one of the most sublime utterances that any human being has ever spoke on this earth?

JOHN CLEESE, ACTOR AND COMEDIAN: No, no. It’s making fun of the guy who has remembered it wrong and of the people who don’t understand it missed

the point.

PALIN: I think that’s really unfair because I think that a lot of people looking and will think that we have actually ridiculed Christ physically.

Christ is played by an actor, Kevin Collie (ph), he speaks the words from the Sermon on the Mount that he’s treated absolutely respectfully. The

camera pans away, we got to watch the back of the crowd to someone who shouts, speak up, because they cannot hear it.

Now, that utterly undermines the —

(CROSSTALK)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: I started off by saying that this is such a tenth-rate film that I don’t believe that it would disturb anybody’s faith.

PALIN: Yes, I know you started with an open mind. I realize that.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, you seemed to have been actually quite angry and irritated with them by the time this debate sort of got fully under way.

PALIN: I was very angry and very disappointed, because John and I had gone into the debate knowing that we were going to be given quite a roughing up,

in a religious sense by a bishop and (INAUDIBLE). So, we — you know, we’d looked and worked out what our answers were going to be and what we felt

about making the film and we were going to defend it.

And there in the end, they didn’t actually even attack us for the content of the film. They just sort of threw abuse around. When the bishop ended up

with saying, well, I hope you make your 30 pieces of silver, I think that was (INAUDIBLE) and I felt — I actually did feel very embarrassed for the

church, for the authorities in the church and for that particular generation. I thought they must do better than that. Come on.

AMANPOUR: I must say that was very vicious because for those who don’t know, that’s a reference to the 30 pieces of silvers that Judas received

for betraying Jesus Christ. The whole world bought into “Life of Brian.” Everybody still quotes it. It’s just still such an amazing cultural

touchstone.

So, talking about the crucifixion, you play a very proper and polite roman, as a group of condemned are coming in and you’re telling them where to go.

Here’s the clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PALIN: Next. Crucifixion?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

PALIN: Good. Out the door, line on the left, one cross each. Next. Crucifixion?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

PALIN: Good. Out of the door, line on the left, one cross each. Next, crucifixion?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: No, freedom for me.

PALIN: What?

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Freedom for me. They said I haven’t done anything, so I would like to go free and live on an island somewhere.

PALIN: Oh, that’s jolly good. Well, off you go then.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Now, I’m just pulling your leg. It’s crucifixion, really.

PALIN: Oh, I see. Very good, very good. Well, out the door —

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes. I know the way. Out of the door, one cross each, line on the left.

PALIN: Line on the left.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, what is that if it’s not mockery?

PALIN: Well, I think that’s — if you look at it closely, it’s actually saying a little something about the time and the historical period. And

that is — you see the background to a lot of “The Life of Brian,” the fact that he — you know, Brian had so many followers was because we had read

that there was a messiah fever at that time. There was the sort of feeling that the world was coming to an end and the messiah was around.

I was just putting, in that character, putting it in place someone who probably come from a very nice family outside Rome and rather comfortable

and being sent off to do his army service in Judea, in this godawful place with all this other strange people. And he was trying to be as

understanding as possible. You know, and when Eric says, oh, you know, no, I can’t. I’ll go to an island and live on this island. Oh, that’s

wonderful. No, he’s just joking. It’s crucifixion, really, which is my favorite line in the film. And power personified by the Romans, being taken

for a ride. People laughing at power.

But, you know, that happens quite a bit in “The Life of Brian,” including, you know, Pontius Pilate when they all roll with laughter at him because he

can’t say (INAUDIBLE), you know.

AMANPOUR: So, listen, you’re talking about Eric Idle there and I’m really interested by what you say about power and skewering power. Now, should be

— I mean, just a land of riches for people who want to do the kind of thing you used to do. Mockery, humor, satire. And clearly, the president of

the United States is a target rich environment.

How do you feel — or do you feel that there has been an adequate skewering in the way you guys did of the current autocratic tendencies?

PALIN: Well, I mean, I feel — you know, take Donald Trump for a start, it’s very, very difficult to be funny and more absurd and outrageous than

he already is. And there really is not much else you can say. You know, people see him as a — (INAUDIBLE). But you know what I mean? People

already see that. There’s nothing much a comedian can add to it. Saying, oh, by the way, do you know Donald Trump has got an orange face? Well, we

all know that. You know, some — hair done at $75,000 a time. All those little things that one might have dreamt up exists.

Now, they’re already — you know, he’s outdone the satirists, and I feel that’s happening — you know, it’s a bit like that here, as well. I mean,

with Boris and his mad hair, looks like somebody that’s been created by a satirical show, but he’s actually the prime minister. So, what do we do? I

don’t know. Just stay quiet. No, you stay quiet. Don’t you try and find the humor there somewhere. But it’s difficult to find at the moment, to be

honest.

AMANPOUR: Back in your day, you used to have the ministry of silly walks and all sorts of things like that. And you must have thought about what it

means to try to get under the skin of modern-day politicians. What do you think is the best way to get under the skin of those who we’re discussing

now?

PALIN: That’s very difficult to know. I think you have to somehow — well, you can quote them back at each other for a start, because what they’re

saying is sometimes so completely outrageous. But otherwise, I think you’ve just got to — you know, you’ve got to find a way — you’ve got to find

another way of looking at what’s going on, not just saying these are ridiculous people. You got to say, there’s something quite dangerous that’s

happening here.

I mean, I would — you know, if I was doing something about Trump or something like that, I would look at the rallies, for instance, because I

think those are quite sinister. I would just have a group of people that shouted at each other all the time. They always shout all the time. You

look at me because that’s the way you are. I’ll shout at you. So, you know, convention of the shouters, which is what it’s all about, it’s just people

screeching at each other. So, maybe one could do something like that.

AMANPOUR: I want to go back to your earliest writing partner and great friend, Terry Jones, who you met at Oxford. And you were in this amazing

bubble from then until the end of his life.

And he died not so long ago, and you gave some very emotional, heartfelt interviews.

Just talk to me a little bit about what he meant to you as a friend, as a colleague, as a collaborator, and then towards the end of his life, as he

started to lose — he had dementia.

PALIN: Yes. Yes.

Well, Terry was just a very close friend from Oxford. And he was someone who made me laugh, but made me think at the same time. He had very strong

views about the world. If I was writing a film or something, he would say, oh, yes, yes, well, I think we should perhaps do this.

And very, very good judgment, very, very good at directing comedy. I mean, “Life of Brian” was brilliantly directed. And then, suddenly, for Terry to

go — to lose the ability to sort of think things through, a man who lived by words, who lived by ideas, who lived by thoughts and arguments, and

debate, to be deprived of speech, it’s just a pretty, pretty awful thing.

But we remained chumps to the end. And it was one of those things. I would go around, and, sometimes, I would think, does he recognize me? Does he not

recognize me? And I think there was always there a glimmer of the 30 or 40 years we have known each other and what we have meant to each other.

So, yes.

AMANPOUR: And again, you all combined have meant so much to the world. I mean, you just have.

And I just wondered, when you — because I believe “Monty Python” first aired on PBS in the United States.

PALIN: Yes, absolutely.

AMANPOUR: Where this interview is also being aired.

PALIN: Yes. Thank God for PBS.

AMANPOUR: What did you think?

I mean, A, how did they get it, and not the other broadcast networks? How did that happen? And how did — Americans are not known for their sense of

irony or…

(LAUGHTER)

PALIN: No, that’s very ironic, the whole situation.

Most of the big American companies passed on it. I mean, ABC. People really didn’t really want the shows as they were played in England. They would

take bits of them and all that.

A man from Dallas PBS station was in New York, looking at BBC product. That was a terrific storm. He was late leaving the airport. He said, what else

have you got? What’s this “Circus” thing? So they showed him “The Flying Circus.” He took it back to Dallas, because he thought it was quite funny,

just one show, and showed it to the PBS team at Dallas.

And they loved it. They said, this is really odd and strange. Have you got anymore? So, they rang the BBC, in New York, and, oh, well, we will look at

the cupboard. Have to go downstairs. Yes, we have got some more. How many? Oh, we have got 44 more.

And he just bought the lot. And they ran them over one weekend, a sort of “Python” telethon in Dallas. They just completely went ballistic on it. And

the — this was picked up by other PBS stations. And that’s how it caught on.

And it was students and it was the younger audience that absolutely loved it. They didn’t understand it, particularly, but it was so different to

anything else that was on American television.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

PALIN: And there were no ads or anything like that. And it was sending up authority. It was sending up everything. And they just said, well, whatever

it is, we love this, because there’s nothing else like it.

AMANPOUR: Recently, you were knighted.

PALIN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You’re Sir Michael Palin. I giggled a bit when I read the reaction of one of your colleagues. Do you know what I’m saying?

PALIN: A taller member, probably.

AMANPOUR: Yes.

PALIN: Yes, that’s right, yes.

AMANPOUR: The one who said, great to see you have been knitted.

PALIN: Oh, no, that was Terry Gilliam.

AMANPOUR: Oh, there you go.

PALIN: Yes. Terry Gilliam said, great to see you be knitted, yes.

AMANPOUR: Just in time for the cold weather.

PALIN: That’s right. That was Terry Gilliam.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: It’s good.

PALIN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: And then the taller fellow, the John Cleese fellow, he said the following about you: “It shows that really hard work can overcome complete

mediocrity. And I think it’s a tribute. It’s an encouragement to all not particularly talented and rather mediocre people to see what can be

achieved by sheer hard work and good luck.”

(LAUGHTER)

PALIN: Yes. No, well, he embodies that so well.

(LAUGHTER)

AMANPOUR: Are you all great friends?

PALIN: We’re pretty good friends, basically, the usual sort of slight problems, management, what we decide to do as a group and all that.

But, basically, we’re very good friends. We still make each other laugh, which is the main thing. And we just greatly miss Graham and Terry. We

really do. I mean, they were such — “Python” was a sort of — it was the six of us, as writers and performers.

And as a little group, we held each other together. Whoever else was employing us, we knew what we wanted to do. And it taught me a lot about

being — about artistic independence and creative independence.

We were able to sort of get through things that people would say, you can’t do that, and we would say, well, let’s have a go. And we did it. And it

worked most times.

AMANPOUR: Possibly because nobody knew what you were talking about, those in authority.

PALIN: Well, yes.

(CROSSTALK)

AMANPOUR: They didn’t know they were being made fun of, maybe.

PALIN: No, no, I think — no, that’s true about satire.

People always think it’s the other person. Oh, it’s not me. It’s him.

AMANPOUR: You’re 77.

PALIN: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Is there anything on the Michael Palin bucket list? When you look down the road, what do you still want to do?

PALIN: I want to keep learning. And I want to keep responsive to the world.

I just — there’s so much going on. There are so many amazing things happening. I know, at the moment, we’re in deep trouble with coronavirus

and all that. But I know we will get through that. And, as a result of coronavirus, I think we will see some very ingenious and inventive work

coming out.

And I’m interested to see what it is. It’s not going to be normal. We’re not going through normal times. So I want to sort of just be able to take

it all in. That’s really it.

And I have always been slightly instinctive. I have never had a big game plan. And things have come up out of the blue, and I hope they will

continue to do so.

AMANPOUR: Well, it’s very nice to see through your eyes the light at the end of the tunnel.

PALIN: Well, thank you, yes.

AMANPOUR: Thank you very much for being with us.

PALIN: Thanks.

AMANPOUR: Michael Palin on how PBS launched “Monty Python” across the United States and across the world.

Our next guest is the former evangelical pastor Joel Hunter. He served as President Barack Obama’s spiritual adviser for eight years, but then he

voted for Donald Trump back in 2016. Well, this time around, he’s backing Vice President Joe Biden.

Remember, of course, Christians form Trump’s base, but Hunter has formed a group called Pro-Life Evangelicals For Biden.

Here he is speaking to our Michel Martin about what made him change.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN: Pastor Joel Hunter, thank you so much for speaking with us.

JOEL HUNTER, PRO-LIFE EVANGELICALS FOR BIDEN: I’m honored. Glad to be on with you.

MARTIN: You voted for Trump in 2016. But you’re part of a group called Pro-Life Evangelicals For Biden. Why did you decide to join this group to

help organize this group?

HUNTER: Well, first of all, we want to make sure that the pro-life agenda is expanded beyond birth. We’re no less anti-abortion, but we know that the

people who die from the pandemic, the people who die from a lack of access to health care, people who die from poverty and the opioid crisis and

suicide and racism and the impacts of climate change, on and on and on, are just as important to God as those people who are still in the womb.

And so one of the things that we want to make sure of is that we are pro- life comprehensively. And we even believe that, if you pay attention to these other areas, it will reduce the choice for abortion. So it will

ultimately reduce the number of abortions. We want to change the culture. We don’t want to just change policy.

MARTIN: It’s one thing to say you’re going to vote for someone in the privacy of voting booths. It’s quite another to sort of go forward and put

a group together to publicly embrace a candidate.

You are lending your personal stature to this enterprise.

HUNTER: Right.

MARTIN: So, why this? I mean, this, I think, is the first time you have done this. Why was this so important to you to do?

HUNTER: I am now an outcast to many people who I was close to.

And I have had to pay a very high price to do this. I knew what was coming. When it — when the article in “The Washington Post” came out about this

movement, and then, the very next day, a large article with my picture came out in “The Orlando Sentinel,” immediately, invitations to preach were

withdrawn. I was taken off the air my daily devotions one of the — on the Christian radio station was taken off the air.

Now, the curious thing about this is, these are my friends, but they were so afraid of losing income and so afraid of losing their constituency, that

they just had to do that. So, I totally get that.

But the point — there came a time in my life where I projected four more years of President Trump and that kind of division and the kind of

hostility and the kind of the tone of personal attack, and what that would do to our capability of making policies that would actually solve the

larger problems.

I know Joe Biden. I worked with him a couple of times in the White House. He’s a good man. And he’s wired to put together those coalitions.

Obama was a master of this, because he wanted people in the room who thought differently than he does. And he had the intellectual capability of

surveying the room, of taking all that information, and then in making a decision.

So, anyhow, it wasn’t just, I can’t do any more Trump. It is, I do think that Vice President Biden has the potential to put together coalitions from

traditionally opposing organizations or people or parties or whatever you want to say, in order to get done what you can’t get done with an up-or-

down vote with one party.

MARTIN: Was there a tipping point for you with President Trump that resolved it for you that you — at the very least, you couldn’t support him

again, you couldn’t vote for him again?

HUNTER: Yes, this started very early, when he started categorizing immigrants as rapists and murderers and…

MARTIN: But that was the first day. Sir, that was the first day.

HUNTER: I know.

MARTIN: That was the very first day he announced his candidacy, but you voted for him anyway.

HUNTER: Well, I voted for him thinking that, OK, this is how he’s running. He’s appealing to this certain base. He’s appealing to people. I knew what

that was.

Then I realized there was a tone being sent down from the leader of our country into all of our country is that this is how we’re going to live.

For people who disagree with us, we are going to count them as enemies. Our rhetoric is becoming — going to become weaponized. It’s not just a matter

of disagreeing with respect. It’s now a weapon. There are winners and losers, and we’re going to become the winners.

And opposite of the Gospel, it is me first, our country first, America first. Nobody else counts as much as we do. And that’s the opposite of the

message of Jesus, which says, love your neighbor as you love yourself. They are as important as you are. And so you spend your life considering not

only what’s good for you, but what’s good for them.

So, that was kind of my progression.

MARTIN: President Trump has said he would deliver conservative judges.

With the assistance of Republican Senate, he has done so. He has delivered on extremely conservative nominees to the — certainly to the Supreme

Court. As you and I are speaking now, his third nominee, unexpectedly, is now being sort of considered. He’s delivered when it comes to that.

And I think some would say, like the same way they said of former President Clinton, if you think he’s a disturbing — if you don’t like him as a human

being, don’t hang out with him, but if these are the things that you want, that’s what you get.

HUNTER: Right.

MARTIN: And why isn’t that enough?

HUNTER: Well, this — that’s the point.

I think that he has delivered. I do not disagree with his present nominee for the Supreme Court. I think she’s a great jurist and a wonderful human

being.

But the point is that, OK, he’s delivered on that. He’s delivered on some of the policies. I’m not against all of his policies. But there reaches a

point of diminishing returns, when you say, who he is as a person or how he approaches the political sphere, in ways that are divisive and accusatory

and will continue to divide our country — the Scripture says, as Lincoln quoted, a house divided cannot stand.

MARTIN: It was surprising to some people that so many evangelical, prominent evangelical leaders fell so hard for President Trump, because he

just seemed to be antithetical to the values that these leaders say they hold.

Why is that, in your view?

HUNTER: There are people who are willing to overlook personal behavior, personal rhetoric that doesn’t match the Gospel, doesn’t match what Jesus

taught us, for the sake of policy support.

And so that’s what a lot of the evangelicals were doing. He promised pro- life legislation. He promised a lot of conservative — he promised to pay attention to religious issues and religious protection. And, in 2016, there

was some fear that the radical left were — would expunge the public square of religion and so on and so forth.

So it’s kind of like the mafia deal, where you pay for protection. And that’s what they saw in President Trump. And, to be honest, that’s kind of

what he’s delivered. He’s delivered justices. He’s delivered certain legislation toward protecting religious liberty, and so on and so forth.

So, they got what they voted for. But, unfortunately, in my view, they got more than they voted for. I voted for him, because I didn’t think that

Senator Clinton — or Secretary Clinton was really going to include faith issues in her administration.

And he had promised — and, of course, I didn’t know who he was. So I said, well, we will take a chance. So I think that there were just a lot of folks

who voted for him the first time who will not vote for him the second time, although he still has a vast majority of evangelicals.

MARTIN: You’re not alone. I mean, there are others in your group, including one of the, as I understand, a granddaughter of Billy Graham, as

part of the group, who said similar things.

She said that being pro-life is about more than being against abortion. It’s about a respect for life in all — throughout life.

HUNTER: We have actually had 5,000 people, over 5,000 people, sign on to that statement.

Now, and the people that organized it were — we have been friends for quite a while. We have had positions of national leadership in the

evangelical world. But, yes, as we say, we want to emphasize the whole counsel of God. We don’t want to just pick out one issue, and back

everything up with Scripture, and make that the litmus test for everything we do.

We want — the Bible says a whole lot about poverty, about helping the alien, about justice issues, and so on and so forth. And we want a

comprehensive biblical approach to what we do in the public square.

MARTIN: I’m intrigued by some of the reaction that you have gotten from people who you consider to be your friends, I mean, like dropping you from

your devotionals and your radio program and all these other things.

How do you understand that? I mean, it just seems like you didn’t renounce your faith. I mean, you didn’t sort of pick your head up and say, you know

what, all the things I have preached all these 30 years, I changed my mind.

HUNTER: Right.

MARTIN: You didn’t say that. You said, I don’t support this particular candidate.

So what does that say?

HUNTER: Well…

MARTIN: And I support someone else. What do you think that means?

HUNTER: I totally sympathize with these people.

I was the leader of a congregation, a pastor of a congregation for almost 50 years. And so I know what it is to not want to divide the congregation.

I know what it is to be protective.

I talked with a young pastor that has a huge congregation in our area. And he’s — and he was one of the ones that said, hey, let’s kind of withhold –

– let’s kind of do your preaching gig in our church until after the elections, and I will have you on probably in 2021.

But he said — he said, Joel, I preached two weeks on Black Lives Matter, and I lost 20 percent of our of our contributions and 15 percent of my

congregation.

And so these are folks that are trying to protect their institutions, their assembled congregation. And so I totally get that. I sympathize with them.

And they’re doing the best they can.

But they’re also very uncomfortable with their position, because they know they should be speaking out on justice issues. They know, when it comes to

matters of white supremacy, with Robert Jones’ book “The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity,” they know these are things that are

important to portray the Gospel as it really is.

But they’re afraid, especially of those voices that — I get mail every day, much of it unsigned, and I will never read anonymous letters. But they

are afraid of the attackers. And there are so many more attackers these days.

MARTIN: Forgive me, Pastor. Doesn’t that suggest that there is a sort of a core of either racism or intolerance in this community that is not being

addressed, that is, in fact, being enabled?

HUNTER: Absolutely.

MARTIN: What does that say?

HUNTER: Absolutely. Absolutely, it does.

And I think — and, full disclosure, right before I transitioned out of the — my pastorate, I had had forums on racism, on gun violence, on the

inequities of the criminal justice system. And I had 800 LGBTQ folks come in and talk about how they’d been hurt from the church.

And the leadership came to me said, you know, you’re — I was 69 at the time. Maybe you should think about transitioning to the next — so, that’s

what they risk is. It’s a Faustian bargain to sell your soul for a little temporary power.

But it’s very easy. And I can tell you, as a pastor, it’s very easy to justify, well, I don’t want to divide the congregation. And what about all

of the staff? Do I put their jobs in danger?

So, it’s very difficult. I don’t want to undersell the difficulty in being prophetic, properly prophetic, in the church. But I got to tell you,

Michel, if the church doesn’t lead in the moral path forward, as far as justice, as far as equality, as far as being comprehensively pro-life, then

we — it’s just not going to get done, because the people — people see us as the conscience.

And if the conscience doesn’t speak up, we will just do whatever’s convenient and whatever is good for our group.

MARTIN: Before we let you go, I was wondering, in a way, if there’s a part of you that feels that this current moment, the Trump administration, is in

a way bad for faith…

HUNTER: Sure.

MARTIN: … because it’s alienating to other people who might otherwise be attracted, who then look at that and say, these people have nothing for me,

and are not willing to speak truth to power, as long as they benefit?

I just wonder if there’s any way you might think that might be so.

HUNTER: Absolutely, it’s true, and especially for the younger generations that have no automatic loyalty to institutional religion.

And they look at that, and they say, wait a minute. This is so different from how I thought Jesus was. This is so different from my — from what I

hear, the love, God is love, and there’s no condemnation in Christ. And this is so different to what I hear.

And so there is a very — I know the draw of power and the draw of withholding your voice, so that you can be near power.

I was President Obama’s spiritual adviser for eight years, or one of them, wrote devotions every week. And I know the temptations I had of not

speaking forward in areas where I disagreed with him. He could tell you that I did speak — I did do that, though.

But I know how easy it is not to say what you need to say in order to be — have a photo-op in the Oval Office. It is just very, very tempting.

MARTIN: How do you feel now that you have put yourself out there? How do you feel?

HUNTER: I feel great. I did the right thing. And so I sleep very well at night.

And I believe that it will give some other people permission to say, I need to think broader than just being anti-abortion. I can be anti-abortion, I

can try to protect children in the womb, but maybe I can help an expectant mother choose not to get an abortion because she’s had the support and the

resources to carry her baby to term.

Maybe there are other ways we can think and accomplish our goals. So, I can live with myself. And I think I’m doing the right thing.

MARTIN: Pastor Joel Hunter, thank you so much for talking with us today.

HUNTER: Thank you.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Democracy is at stake. So is the concept of tolerance.

Finally, tonight, we cast our minds back to a time when one country finally did the right thing. Exactly 30 years ago, South Africa effectively

abolished apartheid, the white supremacist minority rule that segregated everything, like in the Jim Crow South.

The process began earlier that year, when, after decades of pressure by the black majority at home and their allies around the world, South Africa’s

President F.W. de Klerk made this stunning declaration to Parliament:

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

F.W. DE KLERK, FORMER SOUTH AFRICAN PRESIDENT: The government has taken a firm decision to release Mr. Mandela unconditionally.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And with that, after nearly 28 years in prison, Nelson Mandela walked free.

And in his first speech, he quoted the very words that he had spoken during the trial that had sentenced him to prison decades earlier, saying

democracy was something that he was willing to give his life for.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

NELSON MANDELA, FORMER SOUTH AFRICAN PRESIDENT: If need be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And when Mandela was elected president four years later, in a remarkable spirit of reconciliation, not revenge, he named de Klerk as

deputy president.

They were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize together 27 years ago today.

Now, even today, of course, around the world, the clamor for democracy and justice rings loud. So, we end with these images from Thailand demanding

just that.

That’s it for now. Thanks for watching”Amanpour and Company” and join us again tomorrow night.

END