Read Transcript EXPAND

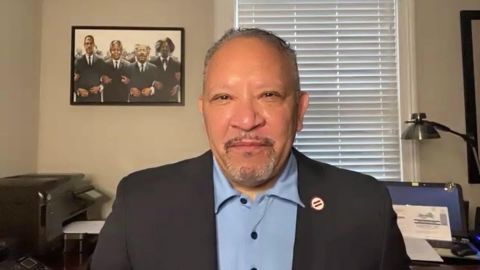

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, as we continue our focus on health, we turn to the role of our cities. Black and minority communities continue to bear the brunt of the pandemic in America and around the world, further exacerbating existing qualities in both health and wealth. Our next guest says that reimagining urban centers could hold the key to closing those gaps. Marc Morial is president and CEO of the National Urban League, the historic civil rights organization dedicated to economic empowerment and social justice. As mayor of New Orleans for two terms, he knows what it takes to run a city. And here he is speaking to our Walter Isaacson about today’s priorities.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thank you, Christiane. And, Mayor Marc Morial, welcome to the show.

MARC MORIAL, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL URBAN LEAGUE: Hey, thank you, Walter. Good to be with you.

ISAACSON: You wrote that this pandemic, it would be similar to, like, the Hurricane Katrina you and I went through down here. It exposed the fragility of our social infrastructure. Is there a way to bring back our social infrastructure better coming out of something like this COVID pandemic?

MORIAL: Well, thanks for having me, Walter. And there is, but the key word is intentionality. It will not happen serendipitously. It will not happen automatically. It will require an intentionality. And that intentionality has to be how we build our public health system, how we build our economic system, how we build our physical infrastructure. And I think we’re at an inflection moment in American history, where we have got important decisions to make in terms of whether we have learned a hard and painful truth and whether we going to do things differently going forward, or whether we’re going to just sort of allow events to control our own future.

ISAACSON: Wait. wait. Drill down a bit. You said health infrastructure. What should we be doing?

MORIAL: I think, with our health infrastructure, we need to rethink. Instead of just pouring billions and billions of dollars into the — quote, unquote — hospital systems of America, we need to challenge the hospital systems, the public health infrastructure, in — as a condition of receiving these funds, that they do things in a more equitable way. And so that involves access. That involves affordability. It involves a wide range of things. It is a big task. But I have great confidence that, if people put their minds to it, and if they acknowledge that to deal with racial injustice and economic injustice, it will not be fixed unless we, one, acknowledge that it exists, until we say our plan has to incorporate the kind of changes, the kind of reforms that are necessary to build better systems and better structures.

ISAACSON: Well, just like after a hurricane, there’s an opportunity not only to deal with the social infrastructure, but the physical infrastructure. If you are looking at cities — you were mayor of New Orleans, you now head the National Urban League — looking at cities, what infrastructure should change?

MORIAL: Well, I think the public health infrastructure must change, how our public health systems work. So, many Americans do not live near a hospital. They do not live near a health clinic. They have no access — many poor Americans, many Americans of color do not have access to a primary care physician. How can we reposition our health system to provide that kind of access? Now, we have — we have telemedicine. We have new technologies and new tools that create an opportunity, but then you have got to — you have got to deal with underlying digital divide issues in order to do it. But, for example, I think we should start with the public health system. Secondly, Walter, I think the economic vulnerabilities of America are being exposed. So, one thing that’s so fundamental is that so few Americans have an economic cushion. And so, once they found themselves unemployed, it was the government, that that was the only resort, enhanced unemployment benefits, checks that they may have received from the government. Well, what do we need to do? We need to think about how to build an economy, and we’re going to have to push up wages and push up earnings, and we’re going to have to force them up in an effort to help people secure a little bit more economic resilience. My vision and my thinking is that what we need is a broad plan, a broad reconstruction plan, a broad renaissance plan. And the government’s going to have to play a big role in it. The private sector is going to have to align with it. The NGO community is going to have to provide ideas and promote it. It’s an opportunity. We have to see this as a challenge, a deep crisis, but an opportunity to learn and build better, and — build better and build in a more equitable way.

ISAACSON: I just read a good article in “USA Today” that was part of their series on race and urban areas. And it was about Essex County, which you know quite well. And it said that the racial segregation in the housing was reflected in the disparities of COVID and health care. How do you deal with that?

MORIAL: Well, look, I think racial housing segregation is a deep and a difficult challenge. One of the things I think we have to confront is the need for there to be more safe, decent and affordable housing in the nation. So, part of my thinking, Walter, is, in addition to dealing with these issues of racial justice, we have to — in conjunction with a plan to build new and more housing. And what we can’t do when we build affordable housing in the 21st century is balkanize it or place it in only certain areas or zones. I think we have seen that mixed-income neighborhoods work better. I think those who’ve had the experiences of racially diverse neighborhoods know they yield strong benefits. There are important new ways. But, at the end of the day, if we don’t have a plan to construct more units, to construct more affordable units — the National Urban League has a project that we will break ground on very shortly in Harlem. We’re building 170 units of affordable housing. We’re building a new National Urban League headquarters. We’re including retail in there, a cultural arts, if you will, civil rights museum. We have worked on this project for a long time. We see it as an example of how you can do it. But it’s required the public sector, the private sector and the NGO sector to work together.

ISAACSON: You were very involved and mayor of the city of New Orleans before Hurricane Katrina, and you watched the city rebuild after that devastating hurricane. What lessons from how New Orleans rebuilt after a hurricane, especially in terms of equity in the education systems and otherwise, did the city get right and get wrong?

MORIAL: At the beginning, Walter, there was an effort, I call it the Dallas plan, that was posited by some business leaders to, in effect, rebuild only portions of the city and decommission many African-American neighborhoods. The rebuilding got off to a bad start. And so it cemented some, if you will, attitudes and points of view. What you got to do is affirm that, in a crisis, everyone is affected, but you have also got to affirm that some are affected more deeply because of their vulnerabilities. And you have got to make sure that the most vulnerable, right, the most vulnerable, those that need, if you will, additional support, get it from the very beginning. I think, in New Orleans, I think once the people began their advocacy, the recovery was better. But New Orleans today has a challenge of affordable housing. It has a challenge of continued gentrification. It’s a city, like all cities, that needs a comprehensive affordable housing plan that brings public, private and nonprofit sectors together, sets a goal with the number of units you want to build, talks about where they need to be built. I’m a big believer, Walter, when I served as mayor, in comprehensive planning that will — followed by aggressive action, not just planning for the sake of planning, but planning for aggressive action What the nation needs now is a broad plan. It may be akin to what Franklin Roosevelt did. It may be akin to what Lyndon Johnson did. It can’t be a series of one-offs or an initiative. We need a broad plan. And the survival of this country depends on it. Racial intentionality and the sense of pulling a coalition of the willing together, pulling together a coalition of people who understand that the strength of the country in our future is going to be our ability to build a nation that truly is a multicultural, multi — multicultural, multiracial, multireligion, multiorientation democracy.

ISAACSON: National Urban League got slammed yesterday by the U.S. Supreme Court, because you had that case saying that the census…

MORIAL: Yes.

ISAACSON: … should keep counting. And you were one of the lead people saying that have to keep counting the system — the census until they get it right. And then you lost. What does that mean?

MORIAL: Well, it means that the Supreme Court is not a Supreme Court that values an accurate count. It raises great questions about the Supreme Court and where their value system is. The census, if they were originalists, like some of them claim to be, then they would know that the text in the Constitution compels the federal government to count every person, and that that value proposition would have basically supported the idea that the census should go on until the end of October. Walter, the reason for the extension of the census is that, at the beginning of COVID, the Census Bureau shut down counting, shut down its field offices for a period of time to keep their employees safe and to keep the people safe. So I strongly believe in the merits of our position, believe that the Supreme Court — the decision of the Supreme Court in the census was wrong and it was unfair, it was inconsistent with the dictates of the Constitution.

ISAACSON: Why is a — the census extension important for addressing the disparities you talked about with COVID? And why did the Trump administration not want to allow the census count to continue?

MORIAL: So, I think the Trump administration and some of the political ideologues in the Trump administration want to — they see the potential political benefits of a, if you will, low count, or an undercount, particularly an undercount in urban communities and communities of color. Why is a full count important? Good question you ask. First because of the apportionment of congressional seats, state legislative seats, councilmatic seats, police jury seats, county commission seats, so that people are fairly represented, so that they get the representation in our legislative bodies that they just deserve. Secondly, the census is the backbone for the statistical formulas for the distribution of some almost — almost a trillion dollars in the federal budget. So, how many Head Start seats Orleans Parish or the city of New Orleans gets or Philadelphia gets or a rural county in Iowa are allocated depends on the census count, the number of children who are counted in that particular county. And I could cite many more examples of why the census is so crucial.

ISAACSON: You have said that racism is the pandemic within the pandemic. What do you mean by that?

MORIAL: I think that race, Walter, is so pervasive that, in the health pandemic, we saw — and Louisiana was one of the first states to release racial information on those who died — have died or those who’ve been affected, that we see these disparities. It’s affecting African-Americans. It’s also affecting Native Americans and American Indians, to some extent, Latinx Hispanic Americans. And those disparities indicate that, within this pandemic that’s affecting everyone that’s, causing infections and deaths in every community, it’s more severe, it’s more disproportionate in those communities of color. And people say why? Well, black people, for example, because I’m most familiar with these numbers, are more likely to get to a doctor late in their infection cycle. African-Americans are more likely to have preexisting respiratory COPD, asthma, diabetes, cardiovascular, anyone with preexisting conditions. And, Walter, the data from China show this early on. The White House knew this early on that any person with preexisting conditions would be more — would be sicker and more likely to face — face the potential of death than any other person. And, in America, when you look at those numbers, when you look at that factor, and you integrate it with the ratio data, it stands to reason — and every physician worth their medical degree understands this, every scientist, every researcher knows this — that means it’s going to have a disproportionate impact. But we see that many communities of color, African-Americans, are less likely to have access to a primary care physician, less likely to have health insurance, particularly in those Southern states, where Medicaid is not expanded, and certainly more likely — more likely to have preexisting conditions. I think, when we see that — but I want to put a really important underscore on that. This does not mean that COVID is a black disease or a brown disease. It is a disease that affects all people. It’s that we have to understand the disproportionality to be able to confront it in an effective way.

ISAACSON: You’re sitting there in New York. I keep reading about people leaving the city, buying homes in suburbs, moving away from cities. Is this a permanent trend, or are cities so resilient, that, once this is over, cities will bounce back the way they were?

MORIAL: I’m confident cities will bounce back. I think young people and emerging generations — I think that New York is unique, because it’s so dense, it’s so crowded. I think many cities don’t have that level of density. So, you can live in the city and still experience some spacing. I think the biggest challenge for American cities is the affordability of housing. I think, in the long run, that is a big challenge. But New York has seen slight rises, slight falls. But people are going to be where the jobs are. And, even if they can work from home, I still think that cities are the most vibrant, the most exciting, the most dynamic centers of American life. And I’m confident that they’re going to bounce back, but they’re going to need support and help. They’re going to need our national government. They’re going to need the energy. Look, Walter, there were people who thought our beloved hometown would never come back. They thought it was G-O-N-E gone, like Pompeii. And the city has come back, now, with continuing challenges with lots of issues, but it fundamentally came back because the people of New Orleans loved it enough, cared for it enough, were willing to fight for it enough, were willing to come back and, against great odds, rebuild their houses, rebuild their businesses. And there were — after many of the stumbles at the beginning, there was funding that was made available. It was imperfect in how it may have been administered. But it came back. And I think New York and many cities are the very same way. I think people will fight, they will work to bring them back, because cities, I think, are the heartbeat of America.

ISAACSON: Mayor Marc Morial, thank you so much.

MORIAL: Thank you. Thanks. Thanks.

About This Episode EXPAND

Former Sen. Carol Moseley Braun weighs in on the Amy Coney Barrett hearing. The W.H.O.’s Regional Director for Europe discusses the disastrous second wave of the pandemic. Sleep scientist Matthew Walker explains how to get better rest in these uncertain times. National Urban League CEO Marc Morial explains how the cities can rethink healthcare and housing in the post-COVID-19 future.

LEARN MORE