Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Our next guest made his career confronting dangerous situations. British Director Orlando von Einsiedel is best known for “White Helmet”, his Oscar-winning documentary about the rescue workers who put their lives on the line to save civilians amid the war in Syria. But in his latest Netflix film, he turns the camera on himself. “Evelyn” is named after his brother who took his own life 14 years ago. It’s a moving portrait that looks at a family dealing with loss and grief. Here is a clip from the trailer.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: He was saying that I’m going to kill myself, like all the time.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: It’s the legacy of what happened and how all of our relationships have been fractured.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You got to open up completely how you’re going to feel later on.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So suicide and mental health are real issues for our time. And Orlando told our Hari Sreenivasan why despite the perilous locations of his previous films, this was his most challenging yet.

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: Orlando, you faced armed militias in the Congo, you’ve run into the rebels with the white helmets in Syria and then your producing partner says how about a film about your family? What is the story that hadn’t been discussed?

ORLANDO VON EINSIEDEL, DIRECTOR: So when Joana Natasegara, my producing partner, she said that, it was like a punch to my stomach. We’ve known each other for seven odd years. And in that entire time, I had never a conversation with her about what happened to my brother. And she knew that something bad happened. She probably knew he took his own life but we just never spoke about it. So for her to suggest one day would I consider making a film about Evelyn and the family, I was almost furious. Because to me, it had come out of the blue. From her perspective, in making all of these really difficult films, she picked up on something that a lot of the crew would go away and cry at the end of the day after witnessing something really traumatic. And she just never seen me really get upset in that way and she’s very perceptive. I guess there’s some block in me that, you know, and it’s probably to do with my brother. And so after initially getting really upset with her, I started to interpret how could I be angry if she’s just asked the question, that really is something that maybe I should look at. And the other weird thing is, Hari, the day she said this to me was the anniversary of my brother’s death. And there’s just no way she could have known that. It was too — it was, like, it was a sign. It was a sign that this was the right time to maybe look at this.

SREENIVASAN: You didn’t even — you say in the film you didn’t say his name really for almost 10 years.

VON EINSIEDEL: Yes. It’s weird. It just becomes your new normal. The normal is to not think about it. I just thought if I ever really go there, it’s so upsetting. It’s so tough to do. I don’t want to –life — you know life is going on and I’m doing other things and I’m immersing myself in other people’s problems so I don’t have to really address my own.

SREENIVASAN: So compare these, like the physical threat and danger that you put yourself into in some of your projects versus really kind of an emotional threat and danger that you’re putting yourself. What is harder?

VON EINSIEDEL: Well, I mean, this is going to sound so strange. I found making this film probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. It’s weird. Physical fear is, yes, it’s very scary and I’m used to being scared in my life a lot but looking inwards, I don’t know. I found it so much more terrifying.

SREENIVASAN: For people who haven’t seen the film. Tell us a little bit about your brother. What was he like? I mean we learn a little bit from the home videos you include in the documentary. But who was he?

VON EINSIEDEL: So Evelyn, he was a gentle, a very gentle boy. We — I shared a room with him for most of my life. He loved the outdoors. He loved walking. He loved camping which is part of the reason we did this in the film, we went on this big walk to all of the places where he loved to go when he was alive. And then towards his — just as he started university, he was studying to be a doctor and he just started to spiral downhill. His lifestyle unraveled. He got depressed. He dropped out of college. And eventually, he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. And just one day, I mean, sadly, for all of us, it seemed like he was on a term that was going better. And just in that moment, he decided he didn’t want to live anymore.

SREENIVASAN: Your family, they all agreed to this? Oh, yes. By the way, remember our brother and let’s go on walks and talk about the one thing that we really haven’t talked about.

VON EINSIEDEL: I sort of felt it would never actually really have to happen. I never really had to go through it because there’s no way my family would agree to do it. And the strange thing was one by one after talking to them, they all said, no, we’d love to do it. It was —

SREENIVASAN: And you’re stuck now.

VON EINSIEDEL: Yes. I was like what do you mean you want to do it? I think, then, this was — they’ve been waiting. Especially my brother and sister, they’ve been waiting for an opportunity to have this conversation. And I guess maybe they’ve been waiting for me to sort of catalyze it.

SREENIVASAN: Let’s take a look at one of the clips with the three of you and your mom on a walk.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: When I sometimes think of him deeply, there are six points that come into my head that I don’t try to think of but they come toward me. One is he used to whisper in your ear.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes, he did.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: The other one was his giggle.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: The other were his twinkling eyes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: The other one was he had the loudest farts.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: I was about to say that.

VON EINSIEDEL: Mom, I can’t believe that’s one of your memories because that’s also — I actually don’t remember the loudness but the smell. That would (inaudible) 10 things I definitely would have listed that as one of them.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: You said he had diagnosis of schizophrenia. I mean it’s a disease but were you angry?

VON EINSIEDEL: After he did it, I was furious because — you know, the sad thing is, and this is one of my regrets is I was angry a lot of the time when he was ill. Because, of course, when anyone is ill, all family attention and resources go into that. I felt that was — I sometimes felt it was selfish because there was four of us as kids and suddenly almost 100 percent of my mom’s time and energy was on Evelyn and I didn’t really understand that. I thought maybe he was being selfish and self-centered. And, you know, it’s only, in hindsight, that I realized that’s a ridiculous view. He was ill.

SREENIVASAN: Then you realize to yourself, wow, what kind of person am I to think about this, right?

VON EINSIEDEL: I have to say, it takes a while for that to come out because when he actually took his life, actually the anger was even more. You know, it takes — that needs to subside and then you start to feel really sorry for him and the pain that he must have been going through and then shame and then grief. I don’t necessarily know how exactly it is in the U.S. In the U.K., suicide is so taboo which is partly one of the reasons this was so hard to talk about.

SREENIVASAN: It’s the number one killer of men under 45 in the U.K.

VON EINSIEDEL: Yes.

SREENIVASAN: That’s a stunning statistic. Why do you think that is?

VON EINSIEDEL: Lots of reasons. I mean I think — and this is something I really learned about myself. I think I thought — more than that, in terms of my emotions and in doing this, I realized that I associated being open and emotional with a sign of weakness. And that — a lot of men feel that. And so when people are ill, they have mental health problems, they don’t often go and seek help. They don’t talk to people because it’s embarrassing. And, therefore, they suffer in silence and they don’t reach out. And it’s in talking to other people and seeking help that you can break that pattern that might eventually lead to suicide.

SREENIVASAN: There are several points in the film where each kind of character, if you will, struggles. And there’s a part I remember where your sister is in a car and she’s crying and she’s saying, you know what, I thought these walks it would all be over. She was looking for a finality. There isn’t one. I mean, he’s gone for the rest of your lives. And you have to live with that emptiness.

VON EINSIEDEL: I think going into this I had a slightly naive Hollywood idea of how this might work. We go on this walk, we’d talk about this thing that none of us could face, and then we would all be healed and live happily ever after. And in reality, that’s really naive. That’s not how grief works. The reality, we went on this, we did talk, and we all built relationship with Evelyn again. That’s something that I’ve taken away. I cherished. I went from nothing. (Inaudible) to talk openly about him and remember all the good times that we spent together. So that – but in terms of the day it finished and feeling healed, no. It’s an ongoing process. And that scene with my sister was recognition of that. At the end of this, she was saying I’m — this isn’t all better but there is progress.

SREENIVASAN: Yes. There’s a scene of some of the progress when you all are walking. Let’s take a look.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Yes.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: (Inaudible) feelings a bit.

(Inaudible)

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: Who is Leon? What did he mean to your brother? Where is the relationship?

VON EINSIEDEL: So Leon went to school with Evelyn and they were best friends. They used to do training, you know, like athletic training together. And that’s what they bonded over. And then since he died, I’ve become close to him. I mean he’s one of my best friends. So he felt he obviously had to come on this walk and join us. And he was so generous. I think he, you know, he found his own way to deal with Evelyn’s death. I think he came on this walk to help us deal with it.

SREENIVASAN: How do we get to the point where here you are on these walks, it’s an incredibly intimate kind of portrayal because the camera is right here. It’s almost like we’re walking with you. And it’s almost natural where people just stop and they have these moments.

VON EINSIEDEL: Walking is an extraordinary thing that for some reason allows you to have this really difficult conversations in this very amazing way. You know, you ask me this question now, it’s very intense. I have to answer. I’m looking directly at you. When you’re walking, you’re not looking somebody in the eye. You’re looking — someone asks you a question and you can answer it in bits. You can pause, you can breathe, you can look at the view. And it just creates this form for open conversations. And so what you see in the film is there are these very open conversations and then it just gets too much. And somebody stops and they just want to cry. They want to hug. And that’s what you see in that moment.

SREENIVASAN: And Leon is also just dealing with the survivor’s guilt. I mean, you see it in part of the film. If I had gotten that phone call, if I didn’t let it go to voice mail, could I have been the man that saved my friend’s life?

VON EINSIEDEL: I think all of us and I think anyone that experienced suicide in their life, I think everyone wracks their brains for that moment. Was there a moment if I had done something, you know, could I have stopped it? I was on holiday when I got the phone call that Evelyn died. Of course, well, if I wasn’t on holiday, if I had been at home, could I have —

SREENIVASAN: It’s your fault.

VON EINSIEDEL: It’s my fault, yes. And you live with that.

SREENIVASAN: How could you not have seen it coming? What kind of brother are you?

VON EINSIEDEL: Precisely. And everyone lives with that who has been touched by this.

SREENIVASAN: Your mother, at one point, said something about her being a single mom and raising you all and here he is her son is schizophrenic. And she was carrying this weight while other people perceive me as the source of — I mean it’s just a huge effect. It’s not just one individual.

VON EINSIEDEL: Well, I guess I’d say two things. I think the first is, on the surface, it looks like a selfish act. The person is actually doing it. They, to them, it’s a selfless act. They have got to a point in their lives where they believe they’re a burden on everybody. And the world would be better off without them. And I cannot tell anyone who might be — who’s watching this, who might be thinking how wrong that is because in this film is testimony to what the devastation is, that 13 years later, a family can’t even talk about this person because of the grief that they are carrying. I — actually one of the legacies, one of the things that’s touched all of us behind this film so much is all the letters that we’ve received from people who said this very thing, they said I watched the film and I’ve struggled with suicidal thoughts for a long time and I now don’t think I could ever go through with it because I’ve seen the damage it will do. And that, for us, is incredible to hear.

SREENIVASAN: You know what is strange is, or maybe it shouldn’t be so strange considering that the prevalence of suicide in the U.K. but you’re walking along this and you’re deciding to share with people why you’re walking. It’s literally the ice cream man that you stop at, shares an incredibly personal story with you and a veteran that you lead on the walk. I mean, it goes — we’re watching the entirety of that conversation and it goes from zero to very deep in 30 seconds. So this is something — probably one of the things I’ve taken away most from this is that there is an extraordinary thing about if you’re open emotionally, honest and vulnerable, it’s almost contagious. So people would see the cameras and they tell what are you doing? We would explain that we’re doing this walk in memory of our brother who took his own life. And people would just suddenly open up completely and say well, that happened to my mom. That happened to my, you know, to my sister. And we’d have these extraordinary conversations with complete strangers. And it was really beautiful. In some ways, the film has done that, too. In a lot of the Q&As we do from cinemas, at the end of the film, people would just stand up, they wouldn’t ask a question, they’d just share. And it was really beautiful when people would just say this happened to me. I just wanted to share it with this room of strangers. It was, yes, it’s extraordinary.

SREENIVASAN: Why is it so hard to talk about?

VON EINSIEDEL: Life is difficult. And we build these barriers around ourselves and, you know, it’s easier to not have to go there and make yourself upset. I think I definitely — I built this big shell around myself and dealt with other things that, I guess, prevented me from ever needing to deal with my own problems. I can’t tell you how liberating it is to actually have these difficult conversations, whatever they might be. It doesn’t have to be about mental health or suicide. It might just be there’s all families have issues, and I think you can find a way forward to have these open conversations and walking is definitely a good catalyst for that. It feels incredible.

SREENIVASAN: Given that you know what the passing of an individual, the impact it has on the family, here you are a guy that has gone into pretty sticky situations. In your next project or the project after that, does this factor into you that maybe I shouldn’t put myself in riskier places because of what will happen?

VON EINSIEDEL: I’ve also just had a child.

SREENIVASAN: That will change the equation.

VON EINSIEDEL: And it already has changed the equation and, I mean, even just going away from home is a much harder decision. So there’s a balance. You’ve also got to live your own life. You’ve got to be true to who you are and what makes you passionate and what contribution you feel that you can make, small contribution you can make to the world. So it’s about weighing it up with your family and your responsibilities.

SREENIVASAN: What are you going to tell your child about their late uncle?

VON EINSIEDEL: Well, my son his middle name is Evelyn. So my brother will kind of live on in him.

SREENIVASAN: Orlando, thanks so much for joining us.

VON EINSIEDEL: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

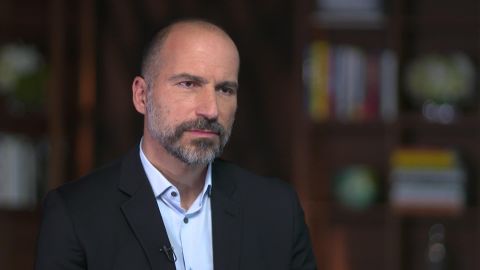

Christiane Amanpour discusses the Trump impeachment inquiry with Barbara Boxer and Elie Honig. Dara Khosrowshahi, CEO of Uber, explains why he is confident about the future of the company despite its loss of billions of dollars in the past three months. Director Orlando von Einsiedel sits down with Hari Sreenivasan to discuss his latest documentary “Evelyn.”

LEARN MORE