Read Transcript EXPAND

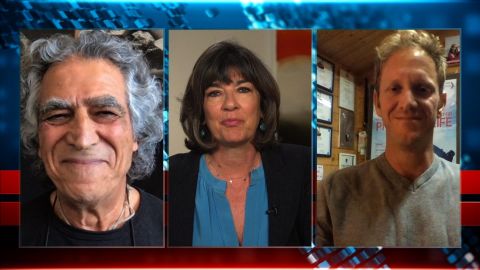

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: And, of course, Afghanistan is America’s longest war. Now, a key source of support for President Trump comes from the white evangelical community of Christians. Reverend Robert Schenk is a clergyman from that very group. And after some deep self-reflection, he changed his mind on some of the so-called culture war issues and regrets his often- divisive rhetoric at the time. He now leads an educational nonprofit which takes inspiration from the anti-Nazi dissident, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who was executed for plotting against Hitler. Here he is now talking to our Michel Martin about embracing empathy in these turbulent times.

MICHEL MARTIN: Thanks, Christiane. Reverend Schenck, thank you so much for speaking with us again.

REV. ROBERT SCHENCK, EVANGELICAL MINISTER: My pleasure.

MARTIN: You had some strong words for President Trump in the wake of his walk across Lafayette Park to — from the White House to St. John’s Church after the military and various police agencies were used to clear the protests there. Why is it that this struck you so profoundly?

SCHENCK: Well, a few reasons. You know my history, as a street-level activist once upon a time on the right, on the ultra-conservative side of the equation. And I know what street theater is. I know how to use props. I have used them. I regret that. I had even used a Bible a time or two. And it’s meant to send a signal. And I think the president was doing exactly the same thing. He was using the Bible as a prop to send a signal to a subset of people who are very important to his reelection. But he did that by seizing control of a church, by using military-grade force, even against the clergy that were present there, evicting essentially an entire sector of the city for what amounted to a political stunt meant to reinforce the devotion of certain voters. And I thought that was a sacrilege. I thought it was profane. I agree with the bishop of Washington, the Episcopal bishop, who is the proper steward of that property, who thought it was an act of religious profanation. And I think it was a very, very serious and egregious violation.

MARTIN: You know, along with Pat Robertson, you’re one of the very few white evangelicals to criticize the president for this, at a time when there’s obviously great unhappiness, anxiety and grief in the country. Why do you think that is?

SCHENCK: I think, first, it points to the moral collapse in my own religious community among my fellows. There was a Faustian deal made with Donald Trump, which went something like this. Donald Trump promised, I will give you everything you have ever wanted on your laundry list of political deliverables, if you give me what I want and demand, and that is religious cover. I need you to say that I’m blessed of God and that everything I have done is good. He defended the photo of — in front of St. John’s Church with the Bible by saying, a lot of Christians think it’s a great photo. And that’s what he needs in the deal. And we made that deal with him. And so there’s a moral vacuum. There is an inability to muster the moral courage to stand up to this. I was delighted to see what Pat Robertson said. The fact he did speak out was terribly important, though a little late in the game, but he did. But my other colleagues have not been able to do that for a number of reasons. One is because they would be assailed by their own constituents now for doing so, but the other is, they would lose access, instant access. They know that Donald Trump will throw them under the bus, will lock them out of the White House, will insult them and disown them in an instant if they displease him. They are aware of that. And so they have to play this game very, very carefully. They’re on very thin ice. They want what they still have outstanding on the list, which is a final appointment to the Supreme Court to give them a rock-solid conservative majority. They’re not going to let anything endanger that, even this kind of supremely offensive behavior.

MARTIN: We keep hearing, particularly from political figures, that, privately, the conversations are different. I don’t know how much credence to give to that, because the fact of the matter is, if you’re a public figure, your public utterances are your record. But I do wonder what kinds of conversations that you have with fellow evangelicals, because quite — in public, the support is as strong as ever. I mean, Ralph Reed, who’s kind of taken over the mantle of the moral majority, as it were, and sort of the politically most active evangelicals, particularly white evangelicals, social conservatives, very strongly defending him. I was just sort of curious about that. The support has been as strong publicly as ever. Are the conversations privately different?

SCHENCK: Well, you know, a year, two years ago, I used to hear my colleagues. They would whisper, you know, I know the guy is way over the top, I know he’s terribly offensive, I know he’s way too visceral, he’s too impulsive, he doesn’t know us, he’s not religious. Look, we know who he is. He’s a secularist. He’s not a believer. But he’s good for us. And who else is going to get this done? And it’s going to take a fighter like him to get it done. Now I don’t hear that much anymore. And that’s even more distressing to me, because what it seems to suggest is that a kind of final conversion has taken place, at least in their thinking, if not in their hearts. And if it is in their hearts, then I fear for them, I mean, in one sense, just in terms of reclaiming their moral integrity, regaining a sense of ethics and what is right and wrong. And if that — if they have lost that ability to discern that, then they are indeed in very grave danger personally, certainly as a community. I mean, we know what the history of demoralized churches are. They quickly become relics of history, and not good ones. And then, of course, there’s — I’m still a believer in salvation. I think we have to have a certain standing before God. And if we lose that, we have lost everything. The Bible even reminds us of that. It says, what does it profit a man if he gain the whole world, but lose his soul? That’s the ultimate loss.

MARTIN: This is according to the Public Religion Research Institute. In March, nearly 80 percent of white evangelicals said they approved of the job Mr. Trump was doing. By the end of May, though, this same group found that Mr. Trump’s favorability among white evangelicals had fallen to 62 percent. That’s according to a recently released poll. Among white Catholics, his approval has fallen very greatly since March. But we have seen this before. In the fall of the president’s — the fall of 2016, the president’s approval with white evangelicals was only 61 percent. He went on to win 81 percent of them in November. So, I guess what I’m saying to you is, is that my reading of this, this isn’t just a leader issue. This is a followership issue. There’s something about Mr. Trump that seems to be deeply attractive to white evangelicals. What is that?

SCHENCK: Well, leaders on every level, from — including the president, but certainly among evangelical leaders, tend to reinforce sometimes what is best in us, but often what is worse than us. So, leaders have a very important role to play in spiritual formation, forming opinions, practices, behavior, beliefs. And they can do that through their role modeling. So, there is a symbiotic relationship. Evangelical leaders are sometimes afraid of their constituents, but their constituents look to see what their leaders are saying and doing to see which part of themselves they should embrace or that they should seek to change. And in this case, there is an opportunity for evangelical leaders to face what is really happening in our country, ask the question, what kind of spiritual family, of religious movement, of identification do we want to have? And we always win when we go with those who are oppressed and marginalized and see it from their vantage point. That was certainly true of early evangelicalism, when we championed the poor and we built hospitals and schools and took care of those who were forgotten in society. When we did those things, we grew as a movement. Now we are losing millions and millions of especially young people. And, right now, the future of American evangelicalism is bleak.

MARTIN: I do know that the Southern Baptist Convention just had their convention. It is the nation’s largest Protestant denomination, and they show a membership decline. It’s the 13th straight year of decline. It’s the largest single-year decline in more than a century. What are you seeing?

SCHENCK: And that’s true almost across the board, and especially when you look at underage 45. And the younger, the worse the statistics become. Young people especially are leaving evangelical churches in droves. And why? Because they see the hypocrisy. They see an identification with establishment power, with political force and influence. They are tired of the combat, the social conflict, the wars, many of them ginned up. Look, I know this stuff personally. I battled with fund-raisers for decades who told me, look, we need to leave your people afraid and angry. The madder they are, the more fearful they are, the more money they’re going to send you. Give us more fear and more anger. I was actually told that explicitly at a conference room table. We need more fear and more anger. Well, young people are sick of that.

MARTIN: You have had some significant breaks with others in the evangelical movement over the years now. I mean, you have broken with them on the issue of expansive gun rights. You have broken with them around the issue of how abortion should be discussed and thought of, sort of a number of issues. And I can imagine that, you know, some people would say you’re the wrong one. I mean, you’re the outlier. You’re the one who is getting it wrong. And, in fact, some people might argue that your point of view is dangerous, that you’re imperiling people’s souls. And I have just wondered how you have reconciled yourself to this over the years? What convinces you and affirms you in your view that your path here is the path that really others should be taking, humbly, I would say?

SCHENCK: Well, it’s been anything but easing, including internally. It’s been a very difficult journey for me. But it started by facing myself, and that was a terrifying thing to do, to listen to my own words and to watch their effect on other people, on the other person. Instead of constantly listening so that I would feel better about myself, I started listening to hear the effect of my words on others. That was part of that process of change. But I’m not alone. There is a book out now called “The Spiritual Danger of Donald Trump,” in which 30 top-level, some of the best evangelical hearts and minds in the United States, writing essays, warning of why the Trump culture, not necessarily Donald Trump as an individual human being, but the political and social culture that Donald Trump represents and fosters, is so dangerous, particularly to Christians. And I go back to, again, what is our message? What are we trying to proclaim and live out? And if I look at the model of Jesus — and if evangelicalism is anything, it’s Jesus-centered. We call it in theological- speak being Christocentric, Jesus Christ being at the center of everything we say, do, believe, proclaim, practice, all of it. The centrality is Jesus Christ. He becomes the model. Too many Christians segregate the world. We are segregationists, into the saved and the lost, those who know God, those who don’t, those who are sinners, those who are saved and sanctified. Well, that’s not the way Jesus treated people. He treated every human being with precisely the same love, respect and dignity. And that’s the heart of the Gospel. So, for me, this is all about returning to my original faith, not renouncing my faith.

MARTIN: What’s the way forward here? We’re in a moment in which there is just a lot of anger and tension in the streets. It’s a big sea change, the fact that you have got some sort of figures who had previously been extremely dismissive of some of the social movements like Black Lives Matter and so forth. They have been very dismissive or critical of them. You’re now seeing them say, you know what? I’m thinking about this. I’m seeing something here, and I think you’re right, and I was wrong. That’s kind of new. So, what’s the way forward here, in your view?

SCHENCK: Well, in fact, we just had a number of evangelical leaders in the — white evangelical leaders in the Washington, D.C., area walk with the Black Lives Matter folks in the streets. It was beautiful to see. And then I just participated in a wonderful, prayerful, Bible-centered celebration at St. John’s Church, where President Trump had that photo-op and held up the Bible. Only, this time, the Bible was actually opened, read, preached, and there were the prayers of thousands of people, and it was — people of many faiths came. What is the way forward? I think, first, for white evangelicals, especially those of a certain age, like me, to maybe preach less, speak fewer words, listen more deeply and much longer, and put ourselves as much as possible – – we can never do it perfectly — but, as much as we can, put ourselves into the experience of another person, sit there, prayerfully, reflectfully for a while, maybe a long while, and feel what they feel. We see Jesus do that on a number of occasions, even to the point where one of his friends died, he stood at the entryway to the tomb and wept. It’s one of the more profound, but shortest verses in the entire Bible: “Jesus wept.” That’s all it said. Maybe this is a time for us to stop talking, like I’m doing now, and instead weep with those, as the Scripture commands us to do, weep with those who weep.

MARTIN: Reverend Rob Schenck, thank you so much for speaking with us today.

SCHENCK: Thank you.

About This Episode EXPAND

Kay Bailey Hutchison discusses President Trump’s decision to pull nearly 10,000 troops out of Germany. Chile Eboe-Osuji responds to the president’s sanctions against International Criminal Court officials. Rev. Robert Schenck reflects on the president’s relationship to white evangelical voters. Amos Nachoum and Yonatan Nir discuss the new documentary “Picture of His Life.”

LEARN MORE