Read Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Now, President Trump has been accused by Democrats of using propaganda and disinformation to discredit those who blew the whistle leading to his impeachment inquiry. Richard Stengel is the former editor in chief of Time Magazine and former undersecretary of state in the Obama administration when he led the department’s counter disinformation efforts. His new book “Information Wars” is a deep dive into the fake news phenomena starting with his own experience with Ukraine during Russia’s evasion of Crimea. And he tells our Walter Isaacson all about combatting false narratives in this social media era.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

WALTER ISAACSON: Welcome to the show.

RICHARD STENGEL, FORMER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, TIME: Hey. Great to be here.

ISAACSON: So this great book, Information Wars, it starts with a Russian invasion of Ukraine. And Hillary Clinton calling you up. You had just become, you know, the undersecretary of state. What does she say to you?

STENGEL: Well, so what happened was in February of 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, the southernmost part of Ukraine, Putin lied about it saying there were no Russian soldiers in Ukraine. And then we saw this gigantic tsunami of disinformation around it focused on the Baltic’s and the periphery in Russian and Ukrainian. And it was new to me. Even though I had been in media my whole life, I hadn’t seen this big Russian engine. But it wasn’t new to Hillary Clinton. She was — had retired as secretary of state. I was just in the office. I got a call on Saturday morning from her office. I thought it was Secretary Kerry, not Secretary Clinton. And I thought she was just calling to say congratulations and well done. And I picked up the phone and it was like a blast of we’re getting beaten by the Russians. The Russians have the big engine. Rick, you need to do more about it. You’re going to be frustrated by the state department. But the state department is still issuing press releases while Putin is on social media changing history. You know, it was like a cartoon version of that. And then she said, you know, get it done and hung up. And —

ISAACSON: She was right.

STENGEL: She was right. And ironically, she knew more about Russian active measures as it’s called, what they were doing on social media than anybody. And yet at the same time, she became the victim of it in 2016.

ISAACSON: So after you start trying to take it on, you were sort of surprised by being kept with insults around the internet from trolls and all. Did you — how did that happen and what did you discover about it?

STENGEL: So, I was trying to get everybody in the state department to be on social media and to tweet and that was not an easy thing. People are reluctant to do that. And I started doing it. And then instantly I got hit by tweets from Russian-sounding names, people attacking me, calling me a hypocrite and a propagandist. And I was a little bit used to it from being editor of “Time” where, as you know, that happens, as well. But I just started to see how concerted it was and how organized it was and it was new to me. And one of the things that I write about in the book is I later saw, which is a little different than even what was in the Mueller report, is that what the Russians were doing was a whole of government effort. It wasn’t just internet research agency in Saint Petersburg. It was coordinated with Russia today and Sputnik and Tusk and coordinated with the foreign minister. So you had the Foreign Minister Lavrov echoing these false statements from the internet research agency within 15 minutes sometimes.

ISAACSON: And our government, according to your book, is just not good at doing that.

STENGEL: I came to the conclusion that government is not the answer. That what this information war that we’re all involved in is not really a state-to-state information war. It’s non-state actors and states involving regular people and government is kind of reticent in this area. I don’t want to be in the counter propaganda business against the Russians and get down in the muck with them. I don’t think that’s the right thing for government. And, by the way, people in government are not very good at it and don’t want to do it. So I thought the best thing to do is enlist the help of people who are good at it to empower people who are good at it and who are doing it. and I thought that was the best role for the state department.

ISAACSON: So what should we be doing?

STENGEL: What should government be doing?

ISAACSON: What should the United States do to counter these Russians who have become masters at what they call active measures?

STENGEL: You know, this is going to be a kind of disappointing answer because I’m not so sure what the government should do in terms of replying back and forth. I think that the government has to change the legislation to allow the platform companies to rebut it. And that’s a longer answer. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which, as you know, treats the platform companies not as publishers, but they get complete liability for what they publish and that needs to be changed. That needs to be reformed.

ISAACSON: Do you think Facebook should be in charge of stopping Russian propaganda?

STENGEL: I think Facebook should be liable for publishing false content, for provably false content, for disinformation, for deep fakes and things like that. I think we should give them liability where they have to take that off their platform, otherwise they won’t have immunity from it, which is what the law gives them now.

ISAACSON: As undersecretary of state, you went to Silicon Valley two or three times to try to say to the companies, the tech companies, hey, you got to at least have some responsibility for what is happening. What was the response of the tech companies give you?

STENGEL: So the focus on that trip where we saw all the heads of the tech companies was really about counter ISIS messaging, about Islamic extremist messaging. And there again, the tech companies actually did a good job. Facebook did a good job. YouTube did a good job. They got this stuff off their platforms. Violent content in their constitutions in their terms of service can be taken off. And they were taken off. In fact, I remember the woman from Facebook likened it to child pornography where the image itself is the crime. So if there’s a beheading video, they would take it down like that.

ISAACSON: So what happens now when we’re going into another election to stop Russia from doing this again?

STENGEL: Look, we’re not going to stop them. The Russians don’t have an off switch. We haven’t even penalized them. I mean, we’ve had sanctions from the annexation of Crimea but no sanctions basically based on what the internet research agency and did like that. So I’m nervous about it. I mean, the Russians have gotten more sophisticated. They’re now using and granting personas from people on Facebook. Mark Zuckerberg in his testimony recently just said they take down a billion false handles a year. Well, a lot of those are from Russians and the Chinese and Iranians. So government is, again, not the answer. People have to have — you know, I’ve always said this, we don’t have a fake news problem. We have a media literacy problem. People have to become much more knowledgeable about it. And the fact that we’re even talking about this is a good thing because I think people will be more vigilant. But it’s more than just that

ISAACSON: Well, people will be more vigilant but the government today, the Trump administration, seems to almost be doing the opposite in its treatment of the conversation with the Ukraine.

STENGEL: Well, I mean as I say in the book, the president is the disinformationist in chief. He’s both the beneficiary and the center of so much disinformation around the world. He gives people permission to do it. I mean, when he gives a constant stream of false statements and lies, I mean the Russians look at that and say yes, we’re all on the same team. So it’s hard for the U.S. government to do that at the same time, but there ought to be new regulations. Very simple one, for example, the platform companies should tell you when they know something is a bot and when something is a human. We should know that. They need to tell you who is buying your information and for what purpose. All political ads need to be completely transparent. You have to know where they’re from, why you’re targeted, who is paying for it. Things like that will give a kind of media literacy and digital literacy to people that will help rebut it.

ISAACSON: Do you think he’s going to have Russia put its weight into re- electing Trump?

STENGEL: Absolutely. And again not so much — and what we saw — they weren’t even for Trump in the beginning in 2015 and even early 2016. They were always anti-Hillary. As you know, he sees Hillary Clinton as his nemesis. And they only later came on the Trump bandwagon. But I think they will support him and —

ISAACSON: Secretary Clinton says they might do it again with Tulsi Gubbard.

STENGEL: I saw that. I saw that. I mean I’m not even going to go that far myself but again, she’s, you know, she’s an expert.

ISAACSON: Fake news, that was something that was originally used to label things that were made up out of whole cloth, especially that the Russians would push through social media and then Trump sort of coopted the term.

STENGEL: Yes, the Russians have used the term fake news about American media for 30 years, basically. And I much prefer the term junk news where it’s kind of fabricated, silly things. And one of the points I make in the book is there’s a fundamental difference between disinformation and misinformation. Disinformation is deliberately false material trying to deceive you. Misinformation is a mistake. And fake news is somewhere in between. I just don’t think it’s a very useful term. The thing to be wary about is disinformation. People who are deliberately trying to deceive you with false information.

ISAACSON: Do you think that the United States should try to fight fire with fire?

STENGEL: I don’t think we should fight disinformation with Disinformation. I think we cannot become the thing that we oppose. And our brand around the world, and I think people still understand it, is that we don’t go to that same level that the Russians do or the Chinese or the Iranians that we do write about that. And I think combatting it with our own message and our own battle of ideas and debate is the best remedy for our brand around the world.

ISAACSON: If you were brought into Mark Zuckerberg and Cheryl Sandburg and said what should we do, what would be your advice to them?

STENGEL: My advice would be take off content that is provably false. Take off content that qualifies as hate speech. Take off things like deep fake, which are false. Take off any kind of speech that directly or indirect leads to violence. Remember, the first amendment doesn’t apply to Facebook. The first amendment applies to government censoring information. Facebook has its own constitution, its terms of service. So I would say have a blanket policy of taking all those things off. No. Like Mark Zuckerberg, I don’t want Facebook making existential decisions about what is fact and false but people have to make those decisions. We as journalists make those decisions every day. A thousand times a day. Why shouldn’t they make that decision and be held accountable for it?

ISAACSON: So you think Facebook should be treated as a publisher not just as a platform where people get to say what they want?

STENGEL: Yes. I think Facebook should be treated as a publisher. Facebook is the largest publisher in the history of the world. The fact that they’re not publishing professional content written by journalists doesn’t mean they’re not a publisher. This is a modern version of a publisher. But they can’t be liable in the very detailed way that “Time Magazine” or the “New York Times” is for every word they publish because the content comes from third parties. But they have to make a good faith effort to take this content off their platform. I think it’s poisoning our whole society.

ISAACSON: You’ve been editor of “Time”. You’ve watched the rise of social media, embraced it marvelously. As somebody who worked at “Time”, I admired how you did it. But do you think that he internet and social media now is undermining traditional journalism and is there a price we’re going to pay for that?

STENGEL: Look, every new technical innovation and communication does something to the previous form of communication. You know, Plato worried that writing would ruin people’s memories. So yes, it is changing journalism. Is there a benefit to humanity and civilization that information is available to people on their phones, that we’re creating as much information in several days as was created through the last 2,000 years? That is a good thing. The fact that some people are abusing it, that people haven’t quite figured out how to process fact from fiction, that people are not as sophisticated about it as they should be, that is a design flaw but I actually think that’s repairable. I think that we can evolve. So, yes. I mean, the reason there are daily newspapers in different cities is that when you’re in Omaha, you couldn’t read the newspaper in Chicago. But if you had lived in Omaha, you could read the Chicago newspaper, maybe there wouldn’t be a newspaper in Omaha. So I’m not sentimental about preserving things that technologically are not necessary anymore.

ISAACSON: We always thought that the Internet, the free flow of ideas would bend the arc of history more to democracy, more towards freedom, more to individual liberty. And suddenly it seems like it’s gone the other way. Why is that happening and what should we do about it?

STENGEL: Yes. So again, I would never have predicted that. And the fact that we have this rise of strong men and authoritarian leaders was not something I would have predicted with the free flow of information. But what has been pernicious, and that’s one of the things I write about in the book, is that this rise of strong men and authoritarians is also accompanied by sophistication of using media and information. They can do a double whammy on people which is restrict the information they don’t want and promulgate the information that they do want. That’s a very dangerous combination. We haven’t really had that in history before. And that is scary. Ultimately, because I’m a kind of information exceptionalist, I think knowledge will win out. But one of the things I write about in the book is that this — the basis of the first amendment, the marketplace of ideas model is actually not working. Marketplace of ideas is this notion that good ideas will drive out bad ideas. Well, there was a kind of a mystical notion coming from Milton and John Stewart Mill and that doesn’t really happen anymore. I think the marketplace of ideas needs help.

ISAACSON: But if the marketplace of ideas isn’t working and good information is not driving out bad, is free speech really a good thing that we should be fighting for still?

STENGEL: Well, you know, one of the things I realized in traveling around the world was that our notion of free speech, the first amendment, is an outlier to people. When I was editor of “Time”, I was close to a first amendment absolutist. Publishing be damned and Justice Holmes’ idea that free speech is not for the thought that we love but the thought that we hate. But as I traveled around the world, and went to the Middle East, and a sophisticated foreign minister say to me, why did you allow that minister in Florida to burn a Koran? Why would you ever want to protect that? And I began to think, well, why would we ever want to protect that? I mean, hate speech, speech that promotes division between people, different religions, and different colors, and different genders is not an awful thing. And some of it has to be protected but some of it should probably be legislated against. I’m actually very sympathetic now to the U.S. adopting some versions of hate speech laws in Europe. Not as strict as that. In part, because there’s a kind of a design flaw in the first amendment in this age of social media. And I know that’s a bit of a high heretical thing to say. But I think we need to start thinking about hate speech laws.

ISAACSON: Rick Stengel, thanks.

STENGEL: Thank you.

ISAACSON: It was good to see you again.

STENGEL: Good to see you.

About This Episode EXPAND

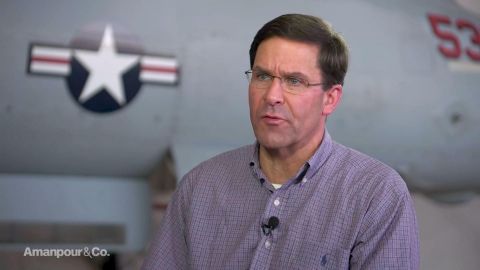

In an exclusive interview, Christiane Amanpour speaks to U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper in Saudi Arabia as thousands of new U.S. troops are deployed to the country to try and visibly confront Iran. Plus, Michel Martin speaks to Tom Mueller about the complex relationship between whistleblowers and society, and Walter Isaacson speaks to Richard Stengel about his new book “Information Wars.”

LEARN MORE