Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.” Here’s what’s coming up.

The rhetorical roller coaster between Trump and the Ayatollahs ratchets up and then down again. What is the U.S. strategy here?

Plus, seven months after his brutal murder, Jamal Khashoggi’s fiance tell me about the toll it has taken on her and why she is now ready to meet with

President Trump.

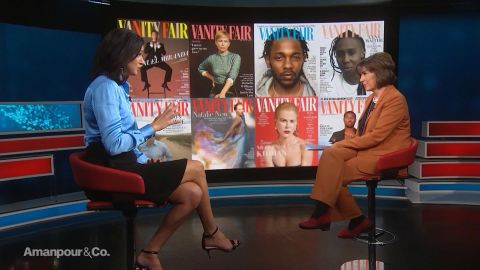

Then from the jazz age to the 2020 presidential race, as “Vanity Fair” opens up its archives to the public, I speak with the magazine’s editor-in-

chief, Radhika Jones.

And —

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: He’ll tell me that I’m small, that I’m young, that I’m inexperienced.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Knock down the House. Our Hari Sreenivasan sits down with the director of that blockbuster documentary about the women who dared to

challenge the establishment in the midterms.

Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

President Trump ran for office promising to put America first and not to get involved in foreign wars. But two years into his administration,

America is in the midst of a brutal trade war with china and edging every closer to a shooting war with Iran.

Members of the administration have ratcheted up anti-Iranian pressure and rhetoric at an unprecedented pace. But is this where President Trump wants

to be? Signing off on yet another Middle East war while still fighting in Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan.

Iran says it won’t be provoked into a first strike. And taking page out of Trump’s book of nicknames, blames the so-called beating for the current

tensions. Bolton, Bibi Netanyahu, Bin Zayed of the UAE and Bin Salman of Saudi Arabia.

Of course, the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, still has not faced any rebuke from President Trump for the assassination of the journalist,

Jamal Khashoggi, in October last year. So, what is the strategy around these clouds of war? I asked Robin Wright, correspondent for “The New

Yorker,” whose latest piece is titled, “Is Trump Yet Another U.S. President Provoking a War?”

Robin Wright, welcome to the program.

ROBIN WRIGHT, CONTRIBUTING WRITER, THE NEW YORKER: Great to be with you.

AMANPOUR: I wonder, you have such deep knowledge of the region and the wars in the region. Do you feel in your gut a sort of similarity, at least

in the rhetoric that is coming from the Trump White House as did from the George W. Bush White House, as they prepared and paved the ground for war

with Iraq?

WRIGHT: Well, certainly, there is a sense in Washington that there are similarities between these two very dangerous Middle East confrontations

with two leaders with whom we have very long histories of hostility. But there are differences, of course, and that you saw the — a confrontation

with Saddam Hussein play out over many, many years.

The recent tensions with Iran, given they’ve just engaged with a nuclear agreement a few years ago, has escalated dramatically within the last week

and arguably, since the president withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal and more specifically, decided to designate the entire Revolutionary Guard

Corps as a terrorist group, which is the first time the U.S. has done that with any army anywhere in the world.

AMANPOUR: Not to put too fine a point on it, but there are many legislators who are very worried. Senator Menendez, the ranking member of

the Senate Foreign Relations Committee has said, “We don’t need another Iraq weapons of mass destruction moment, where we are engaged in a conflict

without understanding, testing the (INAUDIBLE) of the intelligence that might lead to us to set actions. Number two, you cannot make national

security decisions in the blind. And that’s what we’re being asked to do with a lack of information.” What is the end game as far as you can

gather?

WRIGHT: Well, I think you’ve asked the big question, and I think there’s a difference within the administration even over what is the end game. I

think you see different goals represented by President Trump, his national security adviser, John Bolton, and the secretary of state, Mike Pompeo.

The president has actually reached out to the Iranians and said he would be willing to talk to the supreme leader. So, there is that diplomatic

overture. The national security adviser, on the other hand, has long called for regime change. He wrote an op-ed in the “New York Times”

talking about bombing Iran, this was before he took office, as the only way to prevent Tehran from getting a nuclear weapon. And Mike Pompeo has

talked about regime change but with 12 demands that are so sweeping that it kind of sounds like either an overhaul of who is in power or regime change.

So, I think they’re all in unity when it comes to, we don’t want to see Iran become more aggressive, we don’t want to see it threaten either

American interests or allies in the Middle East. But then, I think after that, there is a severe difference, and I think that is beginning to be

illustrated.

But I do think that over the last 10 days, we’ve seen an escalation. And a sense in Washington that something is going on. The big question, of

course, is are the Iranians responding to what the United States has done in terms of saying, “You will not be able to shift any oil anywhere in the

world. Therefore, we’re starve you economically,” and designating the Revolutionary Guard as a terrorist group.

Is it responding by deploying its forces in case there is some kind of action, is it defensive, or is this an initiative to try on challenge the

United States and say, “You’re on our borders, you’re on the gulf waters just off our borders. We’re going to show you that this is our turf”? And

so, it is very unclear what the Iranians are doing. And I think the United States is at a stage where there is very serious debate about what’s going

on and what’s going to happen next.

AMANPOUR: I mean, just very briefly though, just to pick up on something you said, do you believe the reports that President Trump is “irritated,

frustrated,” with the direction in which his national security adviser seems to be pushing him?

WRIGHT: Donald Trump believes national security stops at our borders. He does not want to see foreign engagement. He resisted the request from the

Pentagon to remain in Syria. He has wanted to withdraw forces from Afghanistan. He really does not want another war. But I think he does

want to stand up to Iran, and that’s where, you know, the divide is.

AMANPOUR: So, standing up to Iran, trying to get the other nefarious behavior tamped down, you know, the Iranians have, “You’ve seen us for the

last 40 years. We don’t negotiate under pressure. We don’t cave even under sanctions.” But they are also saying, the foreign minister, the

supreme leader, that, “We do not want war. We are practicing in the face of your maximum pressure, maximum restraint. And that we feel you are

trying to entrap us as a pretext, or a precursor for war against us.” Just give never benefit of your analysis of the Iranians.

WRIGHT: Well, I saw the Iranian foreign minister four times when he was in New York for the United Nations last month. And the message was,

repeatedly, “We do not want war and we do not think Donald Trump wants a war.”

I think the Iranians are very nervous. I think they’re feeling vulnerable because of their economic circumstances with renewed sanctions. I think

they feel that the United States surrounds them, whether it’s in Afghanistan or Iraq or in the Persian Gulf. And I think that this, as you

know better than anybody, Christiane, this is a very proud nation with a long history, and feels that it’s going to take whatever action it needs to

survive.

This is also a revolution, 40 years in, with the revolutionaries in their elderly years, and it is the fate of Iran as a nation, as well as a

revolution that has redefined politics across the Middle East. There is a lot at stake here.

AMANPOUR: I must say, having covered this region for so long, my head is spinning at the speed with which these tensions have been ratcheted up.

So, we’ll wait to see what happens over the next days and weeks.

But let’s continue your theme. In this case, we have U.S. allies in the region, Saudi Arabia, the UAE. And they are saying that it is Iran that

sabotaged tankers in the Persian Gulf, in the Strait of Hormuz. How closely should the United States watch what is being told by Saudi Arabia

and the UAE who are obviously challenging Iran in that region?

WRIGHT: Well, these tensions pre date this tanker episode. There has been growing tension in the Persian Gulf between the Gulf (INAUDIBLE) Saudi

Arabia and the United Arab Emirates particularly and Iran, going back decades. But particularly, since the takeover of Crown Prince Mohammed bin

Salman.

And so, I think that we were on an escalatory path. What happened with the tankers, I think, has soared this into kind of the stratosphere when it

comes to something — going from rhetorical tensions to actual physical dangers of some kind of showdown.

And the United States has long taken a position that Saudi Arabia is one of its most important allies, not just in the Middle East but the world, and

it has stood by the kingdom, whoever is in power. Now, there has been this undercurrent because of the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the administration,

has been under enormous pressure to try to distance itself. At the same time, it is trying to push a Middle East peace plan that will depend

largely on whether it gets Saudi Arabia’s approval. So. that relationship is not going to change in any way by what happens in the Gulf.

AMANPOUR: We’re next going to hear from Jamal Khashoggi’s fiance. There is a lot of commentary about how, you know, seven months after his murder,

there is still no real transparency, accountability, effort by the United States, or indeed, more importantly, Saudi Arabia.

WRIGHT: Absolutely. Jamal Khashoggi was a friend of mine for 30 years. And I am stunned that the administration has done nothing to hold to man

accountable, when the Intelligence Communities all believe the crown prince had some kind of role directly or indirectly in orchestrating this very

grisly murder. The fact is, we still do not know where his body is, and that is reprehensible.

AMANPOUR: We’ll see whether Hatice Cengiz’s presence in Washington might move that dial a little bit, we don’t know. But, Robin Wright, thank you

so much for all of your expertise as usual.

WRIGHT: Thank you, Christiane.

AMANPOUR: And as I said there, my next guest is Jamal Khashoggi’s fiance, Hatice Cengiz.

On October 2, 2018, she waited outside the Saudi Arabia consulate in Istanbul while the “Washington Post” journalist went inside to collect the

papers he needed for them to get married. She waited for hours but he never reappeared.

Now, seven months later, there is no justice for Jamal. But Hatice is working tirelessly to make sure those responsible for his brutal murder and

dismemberment face justice.

The Trump administration has questioned the CIA’s conclusion that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman authorized the operation and has avoided

imposing any substantial penalty on the longstanding Middle East ally. Hatice has been testifying before Congress and I spoke to her about her

message and why she is now ready to meet with President Trump.

Hatice, welcome to the program.

I’m going to start by asking you a couple of questions in English. I want you to respond in English and then we’ll go into Turkish when it becomes

more technical. So, obviously, first, we all want to know how are you doing? What has the last seven months been like for you since Jamal was so

brutally murdered and his body still has not been discovered?

HATICE CENGIZ, JAMAL KHASHOGGI’S FIANCE: I am feeling very bad. Myself — I don’t understand what is going on right now. But I am here in

Washington, D.C. today. I want to understand and I’m finding or seeking about justice for Jamal, and why they are not making anything for this

case.

AMANPOUR: How do you feel personally? How is it affecting you personally?

CENGIZ: I am feeling alone and — I want to speak in Turkish, please.

AMANPOUR: OK.

CENGIZ: Because I can explain by my language better.

AMANPOUR: Go ahead.

CENGIZ (through translator): I feel very much alone about this. I feel I have been deserted. A journalist has been murdered. There hasn’t been a

proper investigation. Everything is in suspense starting with the United States, European countries, states, leaders have not put proper pressure.

They have not taken any steps with a view to getting answers, real answers to this horrendous crime. I am questioning humanity. I feel a moral

responsible to ask these questions and I feel a complete disappointment at the response to his killing.

AMANPOUR: So, just let me ask you then, because, recently, the United States last month publicly designate 16 people from Saudi Arabia for the

roles that they allegedly played in Jamal’s murder. The U.S. says they and their immediate families are not allowed to travel to the United States.

Is that a good first step for you?

CENGIZ (through translator): I would like to think that way. I would like to hope that it is a first step in the right direction. But in itself, it

is not really that meaningful. There has been a murder. The murderers have not been captured. The whole humanity are curious. I am wondering

why no significant real steps are being taken so far.

What happened to his body? For example. No one has given any answers. No one has given any clear-cut straightforward answers to that

question.

AMANPOUR: Saudi Arabia has put some people on trial and they say for the murder of Jamal Khashoggi. What do you want Saudi Arabia, the United

States and the European Union to do?

CENGIZ (through translator): An informational investigation, a board or some kind of a team can be formed. The United States should lead, could

lead such an investigation. I did not choose this but I found myself right in the middle of it.

I am a living victim of this crime. Jamal and I came together. We wanted to lead a life together. We wanted to start a life, a happy life, but he

was savagely, brutally killed, and that our hopes, my hopes were interrupted.

AMANPOUR: Tell me a little about what you remember, what life was like with him?

CENGIZ (through translator): Of course, my relationship with Jamal was very strong. It was a love story from the moment we met each other. It’s

like this. It’s — not just a marriage but a friendship, on a journey together. Maybe a teacher/student relationship. Very joyful. We were

having a good time together, entertaining each other, sharing values. So, losing — when I lost him, more than losing a husband, a partner, I’ve lost

my friend that I thought I would have for the rest of my life. So, I feel that pain.

Yes, it’s been eight months since I lost him. But it’s in my — for me, the feelings are exactly the same. They haven’t diminished. They still

affect me the same way as they had on day one.

AMANPOUR: You know, you paint a very beautiful portrait. And Jamal was also a friend and a colleague to many of us, and many of us miss him and

value him. And also, as journalists, want this murder to be solved.

So, let me ask you a final question. In October, shortly after Jamal’s death, President Trump invited you to the White House, you rejected it

then. Do you think that it would be a good thing for you to go and meet the president of the United States and put your very forceful case to him

personally?

CENGIZ (through translator): Yes, this is a very good question. I would like to thank you for this question. At the juncture we are in now, I do

think about this. I do have hopes. But before I can go and visit him, President Trump needs to renew his invitation.

I am in the United States. I am going to speak to the Congress. Testify at Congress, that’s why I’m here. And communication has been sent to the

White House stating if I have accepted the invitation by the president. So, I am ready to take part in that myself. If — and I do believe that I

might be able to say things or take steps to positively affect the process.

So, to meet the president himself, I would like to meet him. I would like to tell him what my relationship with Jamal was like. At the time such a

step would not have proven an accurate one. The political situation, you know, everything else that was going on. But right now, I feel ready to

meet Mr. President. And so, I’m here to make these steps, taking these steps, and continue my life subsequent to that.

AMANPOUR: Well, we hope that he heard you, Hatice. And obviously, on behalf of all journalists, we want to see a proper investigation and

accountability for the murder of one of our own colleagues, and obviously, your fiancee.

Hatice Cengiz, thank you so much for joining us.

CENGIZ (through translator): Thank you. I would like to thank you.

AMANPOUR: Now, across the world, publishers, editors and reporters are increasingly finding that they must take stand for values and for

truth.

My next guest is the editor-in-chief of “Vanity Fair,” Radhika Jones, and she is no exception. Just over a year into her tenure, she has put her own

imprint on the magazine after following in the footsteps of two titans, Tina Brown and Graydon Carter.

Jones has made diversity her rallying cry. And for the first time, she’s opened up the “Vanity Fair” archives online for the public to see free of

charge, at least for the beginning.

All good scoops are better with a bit of controversy, and Radhika learned that as well with her major coup when her April cover was time to launch

Beto O’Rourke’s campaign for the presidency. Something he now regrets.

I asked Radhika Jones about all of this and much more when she joined me here in our London studio.

Radhika Jones, welcome to the program.

RADHIKA JONES, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, VANITY FAIR: Thank you so much for having me.

AMANPOUR: It’s a year in now. You are editor-in-chief of “Vanity Fair.” How — are you finding your feet — how scary was it, in fact, to take this

massive job on?

JONES: It was exciting, more than anything else. It came little out of the blue for me. I hadn’t really expected it to be — it wasn’t something

that I was necessarily aiming for but it was so exciting that the opportunity came up. So, I kind of threw myself in with a lot of energy.

And it was a very exciting first year.

AMANPOUR: Well, you have done something quite remarkable right now. I mean, “Vanity Fair’s” archives are all available. People are going to be

able to go back at will and look at the cover from 1913 and all the ones they want to. That’s the very first one.

JONES: Yes. “Dress and Vanity Fair.” And it was published by the original Conde Nast, the man. And it was a men’s magazine. It was sort of

a men’s magazine.

AMANPOUR: Really?

JONES: Yes, yes. So, you know, despite the picture on the cover. And it kind of became — it sort of evolved into a magazine for a sophisticated

class, a little more broadly.

AMANPOUR: Which one did you particularly focus on of Tina Brown? I mean, there is the phenomenal Reagan dancing cover that we have.

JONES: Yes. You know, she basically had to fly down to the White House and convince them, after the shoot, convince the Reagans’ press secretaries

to go for it. And she was incredibly persuasive and she put this photo on the cover, and it kind of showed them in this different light from the way

people had seen them. The lightness that they have, the spirit that they have.

You know, it is a very different time now and we might look back on that era differently. But at that moment, it drove so much coverage, and it

really wasn’t the way she frames it in her memoir, in her diary, it was the beginning of her era of “Vanity Fair.”

But I just love the — I love that she went down there personally with those pictures and convinced them to do it because that is — she was a

very hands-on editor. She knew what she wanted and it is very inspiring of the.

AMANPOUR: And I guess everybody now knows the pregnant Demi Moore. And that’s become — even other photographers, other actresses have sort of —

you know, perhaps taken that idea.

JONES: Yes.

AMANPOUR: But this was also unbelievable when it came out.

JONES: This was not common when it came out. And I remember I was 18 years old, I think, when this magazine came out. And it was — you know,

it raised a lot of eyebrows, it got a lot of people talking, it really moved the culture. But what I love about it and what still speaks to me as

an editor is she has this expression throughout, you see it on the cover, she’s so calm, she’s so confident, she’s confident in her body, she is

really owning her pregnancy and her look. And I love to see a woman look like that, and I still do, I still look for that in a cover.

AMANPOUR: Here are your covers, some of them. I mean, not all of them. But I believe Lena Waithe was your first, right?

JONES: She was. Yes, she was my first.

AMANPOUR: What made you choose Lena Waithe?

JONES: Well, Lena was, to me, a very obvious and natural choice. She had won an historic Emmy. She had made this amazing speech that really

resonated with people. She had —

AMANPOUR: What did she say for those —

JONES: She said when she got up on stage and accepted her award, she said, “Our differences are our super power.” And it spoke to a lot of people,

and it still does. And she really — you know, she lives that in her life and in her work.

AMANPOUR: And again, diversity in color. Because, you know, it’s quite dramatic the way so many of your covers have shown people of color. Was

that something very deliberate?

JONES: I mean, it’s something that, when I look around at the culture and what’s happening in the culture, it is something that simply feels

appropriate to me. It feels like these are the people who are on our screens now. This is — you know, this the world of “Black Panther,” of

“Get Out,” you know, these are the rising talents who have roles that maybe they wouldn’t have had 15 or 20 years ago because of the way that Hollywood

is changing, because there are so many more opportunities in television, on streaming platforms, on movie screens.

And so, we want to show that. And if we can lead the way, that’s even better.

AMANPOUR: And the fact of the matter is that whether it is “Vanity Fair” or “Vogue” or these big glossy magazines, sales are going down. I mean, at

“Vanity Fair,” I think they went down about 37 percent over 2018. And I just wonder, how you keep the profile in this era.

JONES: Well, well, a few things. One, just to be clear, circulation is not only stable but rising. And so, that’s another important barometer of

reader engagement and loyalty. And so, we’re feeling good about that. There are simply fewer newsstands than there used to be. So, we grapple

with that problem for sure.

But I am very bullish on the print magazine for a number of reasons. One of them is that covers, as we’re seeing, still hold a lot of power. And

the thing is that they hold power precisely because of the digital environment. Because when we release a cover now, we do it digitally, we

do it on Instagram, we do it on our own site, we do it on Twitter, and we’re finding engagement with readers who maybe had not come across “Vanity

Fair” before but they’re seeing it now because it turns up at their feeds.

And so, when we make choices about who goes on our cover, we’re reaching more people. And that’s exciting. So, that’s one thing. The other thing

is that print still matters even as a conversation driver. And certainly, we saw that with Lena Waithe, we saw that with Beto O’Rourke cover.

AMANPOUR: And that really has created a huge amount of interest. It was so obviously timed to come out as he declared his run for presidency. But

he then got a bit embarrassed, I think, about the tag line, the, “I was born to be in it.” I’m going to play what he said about it and then we can

talk about it.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: You a little guff for it, and probably unfairly because the whole quote was a little bit different.

BETO O’ROURKE (D), PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE, Right.

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: But it seemed a little cheeky.

O’ROURKE: As though I were born —

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: When you saw it, did you think that?

O’ROURKE: Yes. I was frustrated, to be honest with you —

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Yes.

O’ROURKE: — that that was the —

UNIDENTIFIED MALE: Welcome to the NBA, man.

O’ROURKE: Yes. That that was the quote they chose to use.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Well, what do you make of that? I mean —

JONES: I’m glad to be in the NBA, too. No. I think, it’s funny to remember but two months ago, Beto O’Rourke he had not been profiled by a

major national media outlet. It seems crazy now considering how much people know about him now. But he had obviously come — he had risen up

through his Senate race against Ted Cruz. He was a figure of total fascination.

I was hearing about him on the East Coast, the West Coast, he was interesting to donors, he was interesting to our readers. And so, of

course we pursued this profile and it was a very competitive story to be the first outlet to be able to tell his story nationally.

And so, I’m really proud of it. I’m proud that we got it. And I’m proud that it is still driving conversation months later.

AMANPOUR: It really it. But what do you make of it? I mean, if I might just, I mean, he did say, “They took that quote,” as if putting it on you,

you know, the press, there they go twisting my words again. What’s your answer to that?

JONES: I mean, he did say it. And I have felt actually that it is clear what he meant. And I would also say that a lot of people have interpreted

this cover differently. I mean, that’s always the case with covers. You know, I’ve presided over a lot of magazine covers in my day. And the truth

is that you can never game out how something will go over.

But I do think that, what they talked about and what we also thought about when we were working on the piece and have thought about in all of our

coverage of this campaign is, there are big themes that are rising up in the 2020 election. And some of them do have to do with privilege and

accessibility and precedent. And if we are driving part of that conversation, I think that’s exactly what our job is.

AMANPOUR: Are you taking a stand?

JONES: That’s a good question. I came up through news rooms where you held your personal opinions back a little bit. I don’t know how it has

been for you over your career.

AMANPOUR: Yes, yes.

JONES: That said, the political environment has changed. It is more divisive. It feels like the stakes are a little bit different. A lot of

the aspects of 2020 that interest me in other areas are at play, things like identity, politics, and experience and expertise. So. my personal

jury is still out on that.

You know, magazine covers themselves tend not to be endorsements and certainly, that has been our protocol thus far. But it is a long election

cycle and we will be covering it as much as we possibly can, as many angles as we possibly can, as many of the candidates as we can. And so, I think

we’ll see.

AMANPOUR: I spoke to Anna Wintour earlier this year. And she actually said that she — I mean it’s Vogue, it’s a different — it’s not politics

but she gets into the politics. And she said, “Actually, it is time for me anyway, for my magazine, to take a stand.” Just listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

ANNA WINTOUR, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, VOGUE: I don’t think it is a moment not to take a stand. I think you can’t be everything to everybody. And I think

it is a time when — a time that we live in a world, as you would well know, of fake news and stretching to be kind. Let me say, stretching of

the truth.

I believe as, I think, those of us who work at Conde Naste believe, that you have to stand up for what you believe in.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: I mean it is an evolving editorial stance that she’s grabbing and running with.

JONES: Right, right. And I think that’s absolutely right. I mean I think there are varying degrees.

There are probably people who would say that I’ve been taking a stand in terms of what I believe in since my first cover and they would be right.

Whether it follows that I would endorse a particular candidate or a particular platform. I think that’s what remains to be seen.

AMANPOUR: But you leave it open then, do you? Because you have an editor’s letter. We’re going to talk about this month’s in a moment, the

Mother’s Day letter. But you could see yourself, “Vanity Fair” endorsing a candidate.

JONES: It’s on my mind. It’s on my mind.

AMANPOUR: I mean we’re talking as the Alabama state legislature has just passed a draconian Anti-Abortion Bill with no exceptions, even for incest

or rape. And I wonder, is that the kind of case or would a politician who vowed to keep choice alive for women, is that the kind — how do you feel

about that? I mean that affects so many women’s lives and men.

JONES: I mean I feel like it is a travesty. And I think that one thing that I’ve noticed again, working in newsrooms over the last, let’s say,

five years, is that there are certain things that have become politicized that should not be politicized.

Things like racism, things like sexism. Those are not political issues. There’s a certain level at which that’s just the difference between right

and wrong.

So yes. I mean I think there are issues that I feel comfortable taking a stand on. There are attitudes and kind of approaches that I feel

comfortable taking a stand on. And that is a great use of the editor’s letter, which is something that every editor handles differently.

And if I may, one of the exciting things about taking this role has been a little bit experimenting with certain things and finding my voice on that

particular platform.

AMANPOUR: Your sister magazine, “Vanity Fair Mexico”, had Melania Trump on the cover and got a lot of guff for it in the words of David Axro (ph). I

mean is that fair? Why shouldn’t “Vanity Fair” put Melania Trump on the cover?

JONES: I think “Vanity Fair” should. I think that — again, I think people often interpret magazine covers as endorsements and I can understand

why that happens.

But I think as you well know in your career, sometimes getting the interview and broadcasting it, it certainly doesn’t mean that you are

endorsing that person’s point of view or what they stand for. It means that there’s something newsworthy at stake and that is the attitude that I

would take toward a cover like that.

AMANPOUR: What about your own personal life? I mean you re — your mother is Indian. Your dad, American. He was a jazz musician. He was a roady, I

think, right, manager. He was under the grates.

JONES: He was a folk musician and then he was a roady for jazz musicians. Yes.

AMANPOUR: I mean Duke Ellington. Really big, big names. But how did growing up as Radhika in Cincinnati?

JONES: Cincinnati.

AMANPOUR: How did that go down?

JONES: I wrote, I think it was in my first letter, that I always wanted to be named Jennifer. No, not Jennifer. Elizabeth. We had a lot of

Jennifers in my class. You can imagine.

And I had a lovely childhood. It was just not a time when people were really aware of things like multiculturalism in their outlook. And it

perhaps contributed to my being maybe a little bit shy.

But I think one thing that I got from growing up with parents like I had, one, my father who was very involved in the arts and in culture but in a

very particular kind, you know, in the context of music and also music festivals.

I got used to being around people who are very creative and people who really write their own ticket and don’t necessarily conform to

what else is going on. Then my mother, who never expected to raise three American kids, but did so in the Midwest, and who really was as helpful as

she could possibly be in terms of navigating American culture. But also really stuck to her roots on certain things.

I wrote in my May letter that I was quite old before it dawned on me that I had never seen her wear a dress or a skirt. She only ever wore saris or

salakimis (ph) when she dressed up.

And it was — and so I would see her get dressed up when she would put a sari on and they’re so elegant. And she always just looked like herself.

And I loved that about her and I think it had a profound effect on me that I only came to realize later on.

AMANPOUR: And just motherhood must be something that you obviously grapple with. Motherhood, working motherhood, you’re married, you have a child.

I was speaking to Tina Brown before and she also married, two children, putting out “Vanity Fair.” And she said this to me about the pressures

that I guess all women face.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TINA BROWN, FORMER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, VANITY FAIR: I think it is a constant agony really for any mother who is wildly busy. Am I keeping faith with my

children? In fact, when Nicole Kidman got her Emmy and she said this is for the times when I was not there to say good night, I want you to know

darling, I didn’t say good night.

Actually, I thought it was very poignant because I thought women always feel that way. Am I there enough? And there are times when I probably

wasn’t.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Can you relate to that?

JONES: I think maybe I have it a little easier. And I acknowledge that this is — that I feel very privileged to be able to say this. Maybe it is

because I am an older mother and so I had a lot of my living under my belt before I had my child.

There are advantages and disadvantages to being an older mother but I would say that’s one of the advantages. And also, my husband is the lead parent

and that makes a huge impact. I would say I’m happy to have the opportunity to say this, actually, that that is part of what enables me to

do my work.

And we didn’t plan for that. It just worked out that way. I am very, very lucky that it did.

AMANPOUR: And finally, when you sit here, you’re only one year in, what is the “Vanity Fair” of the

Radhika Jones era?

JONES: Well, it is something that I’m thinking about a lot because of the archive launch. So the archive contains 736 issues. It is a lot to go

through and I hope everyone will. It will be free for the first month and then we want you to subscribe.

But one of the things that I love about it is that with the benefit of hindsight, you really can start to get a feel for what I think of as the

narrative arc of a particular era. And when we, as editors and journalists, are in the middle of that era, it can be hard to tease out

what are the stories of our time?

When we look back 20 years from now, 50 years from now, what will we say about this moment? What I want to be able to say is that we found some of

those narrative arcs. We found a new generation of creators and a new generation of talent and we put them on our covers.

And we’ve raised issues that are important to talk about in the culture whether they have to do with equal pay or with male privilege or even just

with how we make entertainment or what we do with our technology and how it affects our lives.

So without wanting to be too grandiose, although I think I just committed that sin, my hope is that we will capture the spirit of our age as it is

developing. It’s always been a zeitgeist magazine and that word is very important to us.

AMANPOUR: Radhika Jones, thank you so much for joining me.

JONES: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: From a female editor-in-chief to a female director making waves, Rachel Lears spent a year documenting the highs and lows of campaigning

against the establishment and challenging the status quo. As so many what the freshmen did in November’s midterm elections.

Knock Down the House won the Festival Favorite Award at Sundance and it became the biggest documentary sale ever brokered when Netflix paid $10

million to show it to the world on its platform. It is an intimate look at history in the making following four female insurgents, including

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, all taking into this system. And as Lears has told our Hari Sreenivasan, it is a very personal piece of work.

HARI SREENIVASAN, CONTRIBUTOR: What’s the story you were trying to tell?

RICHARD LEARS, DIRECTOR, KNOCK DOWN THE HOUSE: Well, I was really interested in telling a big story that was national in scope, about people

coming together from different parts of the country, from different backgrounds, to really work together and find common ground in unexpected

ways.

So I knew that this organization is bringing to Congress and justice Democrats. We’re going to be recruiting candidates among ordinary working

people to run together on a unified slate. And they would all be grassroots campaigns that took no corporate PAC or lobbyist funds.

So I was very interested in what that would look like, both on the human level of what does it take to believe in yourself as an individual, to put

yourself out there in this way. And then also what does power look like in an institutional level around the country, different political machines.

And what does it look like to challenge that power from a grassroots perspective?

SREENIVASAN: I mean there seems to be kind of different through lines here. One about representation. One about money. And then really how

they kind of converge in politics.

LEARS: Yes, absolutely. That is very much what I hope the takeaway will be is that you know, I think there’s an intrinsic connection between money

in politics and representation in politics. When we have a campaign finance system in which it is assumed that it’s going to cost millions of

dollars to run a campaign, a congressional campaign, for example. And that you have to have access to that in your personal Rolodex to be considered

viable.

Only certain kinds of people are going to run for Congress and run for office in general. So really, the only way to challenge that is to build a

new pathway so that people from historically marginalized groups or underrepresented groups can have an alternate path to building power in the

community and getting to office that way.

SREENIVASAN: You followed four different women in the film. We’ve got a clip where they’re kind of almost trying out a stump speech, just really

getting confident. And they’re all kind of in the room watching each other. Take a look.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMY VILELA, FORMER HOUSE CANDIDATE: You know I grew up in poverty. I was raised by a single mother. And so I learned how to fight early on. Now

that my eyes are open, I cannot and I will not close them again.

CORI BUSH, FORMER HOUSE CANDIDATE: The person I’m running against is complacent but I’m not. I myself can deescalate a person with a gun. And

I’m not a police officer. So I wonder how come they can’t do it?

REP. ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ (D-CA): I’m running because of Cori Bush. I’m running because of Paula Jean Swearengin. I’m running because every

day Americans deserve to be represented by everyday Americans.

PAULA JEAN SWEARENGIN, FORMER HOUSE CANDIDATE: And it’s time for ordinary people to do extraordinary things. Let’s raise some hell and take our

lives back. Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: A lot of people are going to be introduced to the idea that there is this infrastructure in place that it had been working in the

previous Congress and it still exists now. What is it about? I mean the new Congress, the Brand New Congress, and the Justice Democrats, what were

they trying to do?

LEARS: Right. So those groups were actually founded in 2016. And those – – by organizers that had come out of the distributed organizing wing of the Bernie Sanders campaign. So they had a lot of experience connecting just

thousands of volunteers around the country to do voter contact, peer to peer voter contact through phone calls, text messages, et cetera.

And so their idea was to really find candidates around the country who would come from the communities they sought to represent. And really, to

have those twin goals of getting big money out of Congress while increasing representation in it.

And the whole concept was that by being a national slate is candidates would support one another through the process because it is very difficult.

Many of them were first-time candidates. But also, that they would be able to activate national networks of volunteers to do some of the phone banking

and text messaging and as well as the small dollar donations.

SREENIVASAN: Is there anything happening on the Republican side?

LEARS: Well, Brand New Congress is actually is a bipartisan organization. They were recruiting and still are recruiting candidates to be on the slate

from the Republican side as well.

SREENIVASAN: And when you look at the space, all of these people came with their own very personal reasons for why they decided to do this to

themselves, right? Tell us about the four candidates that you’ve profiled and why they came into this.

LEARS: Yes. So each of the candidates we’ve profiled has a very personal high stakes reason for getting involved with politics and for running for

office in the first place.

And so the film follows Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez who is motivated really by the experience of growing up between two worlds in the Bronx and

Westchester, New York, really seeing firsthand the facts of economic inequality and the differential opportunities that you have

based on the zip code where you grew up.

And in particular, her family suffered a great deal during financial crisis of 2008. She lost her father who was the main breadwinner at the time.

And that’s when she herself became involved in the hospitality industry just to keep the family afloat and to keep their home. So she really

understands in that first-hand level what economic inequality feels like.

And then we followed Paula Jean Swearengin in West Virginia who comes from a family of coal miners. Just about every man in her family has been a

coal miner, fathers, uncles, grandfathers. And many of them have suffered and died from illnesses related to the fossil fuel industry, black lung

cancer.

So she sees those effects, the health effects and as well as the environmental degradation that’s happening and she is really motivated by

the desire to challenge, the false choice between a clean environment, clean water to drink, and good jobs. She would argue that all West

Virginians and all Americans deserve both.

We also worked with Cori Bush who is a nurse and a pastor near Ferguson in St. Louis, Missouri. And she became a frontline Ferguson activist in 2014

around the death of Michael Brown who was shot by a police officer.

And through that community organizing, she began to feel that the elected officials in her community were not as responsive as they could be to the

community’s needs. So she really stepped out to try to be an alternative there.

And finally, we followed Amy Vilela who ran in Las Vegas, Nevada. And she had not been involved in politics at all in her life until, in 2015, her

22-year-old daughter was unable to receive treatment at a hospital. Amy believes due to the fact that she wasn’t able to present proof of

insurance.

So the insurance system got in the way of her care. And as a result, she suffered a pulmonary embolism. Her blood clot was not diagnosed and she

died at the age of 22 in the richest country in the world. So Amy became politicized around the issue of universal health care and single-payer

health care in particular.

SREENIVASAN: And we’ve got a clip of Amy I just want to take a look at too.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

VILELA: My name is Amy. And I am not a career politician. I was someone who should not be able to run for Congress. I was a single mom, I was on

Medicaid, wick, food stamps. I worked my way through college somehow and became a chief financial officer. Thanks a lot.

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Take care.

VILELA: This is not a game to me. This is not an opportunistic move for me. I turned my back on an executive level job. I sold my house. I’ve

gone into debt.

In the beginning, it was a tough decision. But I would do it again in a heartbeat now.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: She put everything on the line. And three out of four of the people that you profiled did not win their elections. Were you as a

filmmaker ready for all four of them to lose? Because Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez pulled off an amazing offset. She was not expected to win that day.

LEARS: That’s right. We were very prepared for all four of these candidates to lose. That was part of the reason that we chose people who

had very strong personalities and a charismatic on-screen presence and their very personal stories that were motivating them.

We knew that we needed those things to really carry the film forward with an uncertain outcome. But we were also very interested in looking at races

that would allow us to explore the nature of power in this country. Really looking at what political machines look like in different parts of the

country.

We’re thrilled, of course, that it includes this historic victory. But I think that a lot of the substance of the film was consistent throughout the

process from development through to execution. And I think we made sure to include the races in which the candidates don’t win as part of that

conversation.

So we want to offer audiences a bit of hope but also realistic expectations about how hard it is to do this kind of thing, to have a really nuanced

conversation about what these times of grassroots campaigns look like.

SREENIVASAN: There’s an interesting bit where Amy, the character who we just watched after she loses, she gets the support of a phone call from

Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. She said it might have to take 100 of us —

LEARS: For one of us to make it through, a hundred of us have to try.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

UNIDENTIFIED FEMALE: Some of us are going to get through. It’s about the whole movement.

OCASIO-CORTEZ: For one of us to make it through, a hundred of us have to try.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

SREENIVASAN: There’s — the inverse of that is also you showed that political power and machine and the interconnectedness of the money when

you realize that Joe Crawley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’ opponent here is making donations to races in different places around the country.

LEARS: Sure. I mean established politicians often donate to — if they raise more money than they need for their own race, they frequently support

one another. And so certainly, when you have an open seat like the seat in Nevada’s fourth district, Amy was actually running against the incumbent

and then dropped out because of Me Too allegations and it became an open seat.

A lot of other folks jumped into the ring at that point. But most of the networks of power, both locally and nationally, got behind one opponent,

Steven Horsford. So Joseph Crowley, who was known in the party as a big fundraiser, he didn’t run.

As noted in the film, he hasn’t had a primary challenger in 14 years and never had a serious challenge. It’s an 88 percent Democratic district. So

the money he raised around, generally around $3 million a cycle, he dispersed to other races around the country. And in this case, Steven

Horsford was one of the races he chose to support.

SREENIVASAN: Because Amy Vilela’s race was almost a little bit of a bellwether of this if we can kind of suppress or tamp down the opposition,

it is better for this race in New York.

LEARS: It may have been. That was the interpretation of her staff at the time. I have, of course, no idea what exactly the strategy was.

It was also a swing district. And so I think Crowley was also supporting the Triple C-endorsed candidates of a lot of swing districts.

SREENIVASAN: Did any of the incumbents sit down or agree to an interview?

LEARS: They did not. We did try hard to get all of them and none of them was willing to speak with us.

SREENIVASAN: This is not just a film for Democrats.

LEARS: Absolutely not. It’s very much — there is no Democrat versus Republican race that we cover in the film. And all four are Democratic

primary contests.

And so the film is really about the relationship among money, party politics, and social movements. And money and politics is a nonpartisan

issue. The issue of representation, of regular working people in Congress is a nonpartisan issue.

We’ve had some great responses from Conservatives who have seen the film at Sundance or voiced their opinions on Twitter, for example. Just that you

know, even if they don’t agree with the political positions that the candidates take, they respect the hustle and the work, and the goal of

increasing representation in our democracy. So we hope that people can engage with it no matter where they are on the spectrum.

SREENIVASAN: Regardless of whether they’re Democrat or Republican, what do you hope a potential candidate watching this film walks away with?

LEARS: Well, I hope people who watch the film feel compelled to engage whatever their capacity is. Whether it is voting. I’ve seen a lot of

people tweeting like, oh, wow, I’m going to make sure I vote now after this.

And if someone feels called to run for office, we’ve also seen a lot of people feeling inspired after the film to do that. I hope it gives people

the sense that it is worth trying. It’s going to be hard but that building networks of support in your community, and among other candidates, is

really going to be a crucial part of that process if you’re a first-time candidate.

SREENIVASAN: Most of America knows what happened to Alexandria Ocasio- Cortez after the election night. The other three women, you’ve stayed in touch with them. Where are they now? What are their plans?

LEARS: Yes. So I’ve stayed in touch with all four subjects of the film. Cori Bush has already declared that she’s running again in Missouri’s first

district. Her volunteers actually never stopped campaigning for her. She took a bit of a break after last year’s election but they continued

organizing. So she’s going to have the ring again.

Paula Jean Swearingen in West Virginia has said that she’s running again but she’s still weighing her options around a few different races. And Amy

Vilela is writing a book about her life experience.

There are a lot of details that didn’t make it into the film, of all of the stories but I think in a lot of ways, Amy’s in particular. And so she’s

writing a broader story of her life, as well as she’s considering running again but aiming right now towards 2022. And she might be spending the

cycle supporting other candidates.

SREENIVASAN: Thanks so much for joining us.

LEARS: Thank you so much. I really appreciate it.

AMANPOUR: And you can watch her documentary, Knock Down the House on Netflix right now.

That’s it for our program tonight.

Thanks for watching Amanpour and Company on PBS and join us again tomorrow.

END