Read Full Transcript EXPAND

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: Hello, everyone, and welcome to AMANPOUR AND COMPANY.

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

VOLODYMYR ZELENSKY, UKRAINIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): The Russian tanks knew that they were firing with a direct fire at the station. That is

terror of an unprecedented level.

AMANPOUR: Russia attacks a Ukrainian nuclear power plant, a very close call, says the head of the U.N. nuclear watchdog. Rafael Grossi joins me to

assess the threat level.

Then:

VLADIMIR PUTIN, RUSSIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): It is clear that we are fighting the neo-Nazis, the Nazis. And we can see that in the course of

the fight.

AMANPOUR: Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and historian Anne Applebaum exposes Vladimir Putin’s baseless claims and invented history.

Also ahead:

SUSAN GLASSER, CNN GLOBAL AFFAIRS ANALYST: What the U.S. and its allies have done is to declare economic war on Russia.

AMANPOUR: “The New Yorker”‘s Susan Glasser tells Michel Martin how President Biden is standing up for democracy against Putin’s war.

Plus:

SERENA WILLIAMS, PROFESSIONAL TENNIS PLAYER: We changed it from being two great black champions to being the best ever, period.

AMANPOUR: Tennis great Serena Williams on how she and her superstar sister, Venus, conquered the court and honor their father in “King Richard.”

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Christiane Amanpour in London.

“Stop Russian nuclear terrorism,” those are the startling words of the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky after Russian forces fired on the

Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant. Ukrainian authorities say that Russian forces have occupied the facility, but radiation levels appear normal.

What’s worsening, though, is the humanitarian crisis. More than a million people have already fled the country. NATO is accusing the Kremlin of using

cluster bombs, while the E.U. foreign policy chief says the Russians are — quote — “bombing and shelling everything.”

And the Ukrainian foreign minister warned the world not to let Putin turn his country into Syria.

A U.S. defense official says that Moscow’s forces have remained stalled 15 miles north of the capital, Kyiv, for days now. The head of the U.N.’s

nuclear watchdog, Rafael Grossi, tells me today’s attack was a close call.

I managed to catch him on the phone just before his flight to Iran, amid talks to try to revive that nuclear deal. He says the Ukrainians are

actually still operating their plant, but under stressful circumstances.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

RAFAEL GROSSI, DIRECTOR GENERAL, IAEA: We were in contact through the night with the operators at the plant, with the regulators of the Ukraine,

myself, with the prime minister. They’re talking to all of them, offering assistance.

And, luckily, the situation did not degrade into a nuclear accident. There was no release of radioactive material. But, of course, it was a close

call, and an indication of something that we have been trying to say over the past few days, in the sense that this unprecedented situation of a

conflict ongoing in a country that has such a big nuclear infrastructure is, of course, something that adds a very concerning element to something

which is, in and by itself, a very grave international situation.

AMANPOUR: Mr. Grossi, what would have happened if one of the reactors had been hit?

GROSSI: Well, if one — it depend — it would depend on the kind of, of course, impact that you would have.

Normally, reactors are well-prepared to withstand external forces like this or even a plane crash. So, there is a good degree of protection. But in a

worst-case scenario, what you would have is the release of radioactive material, which is the core of the reactor, so, indeed, a serious

situation.

AMANPOUR: Mr. Grossi, did you…

GROSSI: Yes.

AMANPOUR: Have you been able to talk to the Russian authorities? You say you were in touch with the Ukrainian authorities? Have you been able to

talk to the Russian authorities, either ask them what they were targeting and why, and to cease and desist?

GROSSI: Yes. Yes, of course.

My normal interlocutor is Ukraine, because this is about Ukrainian facilities. But the realities of the ground are — of course, indicate that

Russian forces are there. So I have to talk to them.

And what they maintain is that there is no targeting whatsoever of these facilities and what happened was an accident. So, in any case, what I’m

telling them and I’m telling everyone is that utmost restraint should be exercised in and around these type of facilities, because, wittingly or

unwittingly, you can very quickly go into a disaster.

AMANPOUR: Right.

GROSSI: And this is why we are so concerned.

AMANPOUR: And my final question to you is on a bigger scale here.

Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons stockpile to Russia in 1994, in return for a guarantee of its sovereignty and territorial integrity. Doesn’t this

complicate your conversations with countries like Iran and others, who say — I realize Iran does not have nuclear weapons, according to the IAEA and

according to the government — but any country now, after seeing a non- nuclear country invaded by another country, why would they want to give up their nuclear weapons?

GROSSI: Well, it’s a bit of a hypothetical or a totally hypothetical question.

But I would say the following. Had Ukraine or any other country had nuclear weapons in its possession, what we are witnessing now would have been much,

much worse. Nuclear weapons do not give security or safety. It is completely the opposite. So I think that decision back in the early ’90s by

Ukraine was a very wise one.

And countries who do not have nuclear weapons should never have them. And this is part of my job.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

AMANPOUR: So, catching up with the director general just before I could get into the studio to ask who actually orders their forces to attack a nuclear

plant. The Russians, as he said, claim it was an accident.

But, still, what is Putin’s version of reality? What would a Russian victory look like for him, for Ukraine, for the world? Today, he seemed to

dig in further to Orwellian logic, insisting that Russia would actually benefit from the unprecedented sanctions that have been levied.

But his unprovoked war has produced the unintended side effect of an international community united in a way that seemed impossible just weeks

ago.

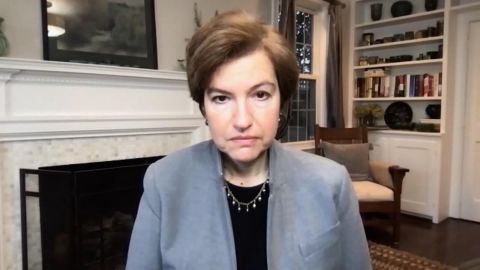

So, for more, let’s bring in the Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, author, historian Anne Applebaum.

And she’s joining me from Washington.

So, Anne, let’s just try to answer a couple of those questions that I that I posited. It looks, to us, anyway, that Vladimir Putin is — keeps

creating this alternative reality for himself, and I guess for the people. How much of that is resonating? And how long can he keep that up, so to

speak?

ANNE APPLEBAUM, “THE ATLANTIC”: Yes, Christiane. You’re exactly right.

He’s trying to create an alternate reality, one that exists in his own mind. And he’s trying to spread it and keep it, and so that the Russian

population sees the same thing. The most frightening aspect of it is that, in his alternate reality, there is no such thing as Ukraine, there is no

Ukrainian nation.

The kind of rhetoric and language that he’s been using about Ukraine is genocidal. He’s talking about eliminating them, removing them from a map,

talking about them as if they didn’t exist. And, of course, this is the rhetoric that’s behind the bombardments of civilian infrastructure,

apartment buildings, kindergartens, hospitals that we have seen over the last few days.

Russians are seeing none of that. None of this is on Russian television. And the Russian authorities are now cracking down one by one on all kinds

of Russian independent media and foreign media in the country.

So the idea is going to be to create an alternate world in which Ukraine magically disappears, and the Russians have nothing to do with it.

AMANPOUR: You know, you use the word genocidal, and I know that you have chosen that carefully and you’re not just flinging that word around.

And it’s really, I guess, key, because, yesterday, we interviewed the chief prosecutor of the ICC, who has been asked by 39 countries to launch an

investigation into the possibility of war crimes. So, let me put this to you. This is what Putin said again on this topic just yesterday.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PUTIN (through translator): I will never give up my belief that Russians and Ukrainians are one people, despite the fact that part of Ukrainians

were threatened and tricked by Nazi nationalistic propaganda and some, of course, consciously followed the Banderites, those Nazi henchmen who were

fighting on Hitler’s side during World War II.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: So, Anne, let’s just put that into context again.

Of course, yesterday, we showed these videos of these wonderful elderly Jewish women basically, actually, who knew the history and who was shelling

them and who did in World War II, and they asked Putin to just leave and get out, because they don’t buy what he’s saying?

How far can he get away…

APPLEBAUM: So…

AMANPOUR: Yes, go ahead. Fill in that blank.

APPLEBAUM: So, Ukraine is a state that is a multiethnic state. It’s open to Ukrainian speakers and Russian speakers. It has a Jewish president. It’s

been very tolerant of the Jews who live there and of the other nationalities who live there, up until now.

What Russia is trying to do is black in the name of that state in the eyes of Russians — sorry. What Putin is trying to do is to blacken the name of

that state in the eyes of Russians. And because most Russians don’t think of Ukrainians as being their natural enemies — in fact, they think of them

in a fraternal way, as a kind of sisterly nation, where many people have relatives, many people have traveled, many people know it well — he needs

to come up with the most extreme language possible in order to change the nature of that state.

So he wants to turn what is, in fact, an open and tolerant society into a fake Nazi state. I also think he’s using the word Nazi not by accident.

What he’s trying to do is pull apart really the memory of the war and the norms that have been adopted in Europe since the war.

He’s trying to — the word Nazi itself is going to become less powerful because of the way that he’s used it in this context. So he’s trying —

he’s attacking the language of peace and stability in Europe, as well as the Ukrainian state, in order to enable Russians to accept what he hopes

will be an eradication of Ukraine.

AMANPOUR: You have written many books about that whole area, one of them in general about the issue called “Twilight of Democracy.”

And you have also noted, as many have, that this appears to become the battlefield between dictatorship and democracy. We know President Zelensky

has been saying that. And the West has united in a way that, as we said, was almost unthinkable just before the invasion.

How do you perceive that and the strength and the change there?

APPLEBAUM: So, absolutely, it is true that this war is happening because it is Putin who sees democracy as a threat to him, to his personal

dictatorship, to his kleptocracy, to the hierarchical society that he commands.

He understands that the language of democracy, the language of rights, the language of — the aspirational language of anti-corruption, of fairness,

of justice, these are threats to him. And he’s not wrong. His system seeks to exclude those ideas and crush them.

And so, yes, it’s absolutely true that, in that sense, he’s declared war on democracy in Ukraine, but also democracy more broadly. And I think

Zelensky’s actions and words, but also the actions of the Ukrainian people, have helped others in the West understand this.

It’s been clear for a long time that this is Putin’s aim, but I think only now have Western democracies galvanized around this idea and understood

what it means and what it could mean for them, that an attack on Ukraine is only the beginning of what could be a much deeper and broader attack on

European democracy more broadly.

AMANPOUR: So, I know you think about this a lot. And you often spend time living in Poland, where you have a home. And I wonder whether you can

imagine, what if Russia wins? What does it look like? What does it mean?

APPLEBAUM: So, everybody in Poland, everybody in the Baltic states, everybody in Central Europe, maybe even many people in Germany are already

beginning to imagine what that would look like.

To have an aggressive Russia, imperialist Russia, which is seeking to expand itself, on the borders of Poland, on the borders of Europe, means

that all of us are in danger all of the time. We’re in danger from accidental warfare. If there’s going to be a Russian occupation of Ukraine,

there would be a long-term Ukrainian resistance.

It would find shelter in neighboring states. Weapons would come into Ukraine from neighboring states. Those are immediately going to be sources

of instability. We can all imagine a world in which Putin says, Ukraine isn’t enough. I have controlled Ukraine, but I haven’t controlled the

sources of democracy outside of Ukraine.

I think the — it’s very important to remember that Putin began his career as a KGB officer in East Germany. He remembers a moment when there was a

certain a Soviet empire that occupied all of Central Europe, as well as half of Germany.

He has made clear in speeches he’s given in the past that he dreams of reinstating something like that again. His foreign minister in the past has

questioned whether German reunification was legal. He may well have designs even on Berlin.

I do think people in Germany have now understood this. It’s one of the reasons why we have seen such a sea change in the conversation in Europe

over the last few days.

AMANPOUR: I mean, again, you just said he may even have designs on Berlin. It’s really hard to even — to even — to clock that, really. It’s really,

really difficult to understand that this is happening in the middle of Europe in 2022.

Do you believe — and he spoke with President Macron, and certainly the Elysees put out their read of the conversation, saying, the worst is yet to

come, that Putin said the — he doesn’t call it a war, but it’s going to continue until he gets what he wants. He will either get it around the

negotiating table with Kyiv, or he will get it on the battlefield.

Is there any off-ramp at all that is possible, any interlocutor of China, India, Israel, I don’t know, who you think has any chance of making a

diplomatic end to this?

APPLEBAUM: So, I do profoundly and deeply hope that there is an off-ramp, that the Russians will both — both because they’re facing much stiffer

resistance in Ukraine than they accepted — they have been taking very heavy losses, both in equipment and people — and because the sanctions on

their economy will begin to kick in, in the next several weeks.

I do hope that they will see the light, they will find a face-saving way to leave. I don’t really care which country it is who negotiates it or

facilitates it, if it’s China or America or anybody else. That would end the conflict, at least for now.

I mean, what I fear is that Putin’s statements that he’s made on Russian television and to the international audience are so — so ambitious and so

broad. He has said repeatedly that Ukraine cannot exist as a country. And so the question is, would he be willing to pull back from the Ukrainian

borders?

I hope that the combination of economic and military pressure will force him to do that.

AMANPOUR: And, as you say, what, what he’s been saying to the country.

And, again, we mentioned that a whole new raft of laws were passed by the Duma today criminalizing criticism of the military and criminalizing just

basically criticisms of this operation, which they refuse to call a war or an invasion.

I spoke to the editor in chief of the last remaining independent station, Rain, or Dozhd. And he — I asked him whether he feared for his life, and

that was a couple of days ago. Here’s what he told me.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

TIKHON DZYADKO, EDITOR IN CHIEF, TV RAIN: Of course, I’m concerned. I’m concerned about my safety. I’m concerned about safety of my wife, who is

the news director here at TV Rain. I’m concerned about safety of something like 200 people who work Dozhd.

So now we have to sit and to think what to do next.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And, of course, they did the next day decide to leave and to suspend operations, for their safety.

How much is that going to matter to the people in Russia, in terms of any kind of alternative avenue of information?

APPLEBAUM: I mean, look, with this war, Putin is destroying two countries, because he’s destroying his own country as well. He’s wrecking all

remaining intellectual and political life, all open conversation.

He’s creating a nation of fear, the kind of nation that Russia used to be the first time I visited it in the 1980s. He’s going to wind up shutting

the borders. He’s going to shut down the economy. The destruction in Russia is going to be profound and long-lasting and will — and is the main thing

that he will be remembered for.

This is the irony that somebody who thinks he’s making his country great is in fact destroying it. So, along with Ukraine, which he is bombarding every

day, he’s inflicting terrible pain and tragedy on his own country.

AMANPOUR: Anne Applebaum, thank you so much for joining us.

And our next guest says the President Biden must rally not only a divided America, but the whole world, against Putin’s aggression.

Susan Glasser is a writer for “The New Yorker.” And she was Moscow bureau chief for “The Washington Post.”

And she’s joining Michel Martin to discuss how the U.S. president should respond to Putin’s war.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

MICHEL MARTIN, INTERNATIONAL CORRESPONDENT: Thanks, Christiane.

Susan Glasser, thank you so much for joining us today.

GLASSER: Thank you for being — for having me today.

MARTIN: You have such a deep expertise in the region and in the subject.

But I want to start with the U.S. perspective. Do you feel that the strategy that the administration has laid out so far will be impactful? I

mean, there’s been an emphasis, of course, as I think people know by now, on economic sanctions. There’s been a lot of certainly tough rhetoric.

There’s been a lot of consultation allies.

And there’s been the delivery of, or at least the promise to deliver sort of lethal weaponry to Ukraine, however they’re going to get it there at

this point. But do you see these measures having an impact?

GLASSER: So, yes, first of all, a dramatic impact.

Basically, what the U.S. and its allies have done is to declare economic war on Russia. And we are seeing an extraordinary consequence of this. This

is the kind of thing that people in Washington, kind of policy wonks at the Treasury Department have said for years, well, yes, there’s a lot of bigger

things we could do. But that would cause catastrophic consequences in Russia. And that’s why we haven’t done them.

And we’re seeing that this week. It is — those are some big guns economically. And Putin has never really been someone who focuses on kind

of economic tradecraft. And I think maybe even he is stunned at the extent to which the United States and its allies have basically cut Russia off

from the world right now.

So what effect will that have on Russian society? In the short term, clearly, unfortunately, it’s causing a new Iron Curtain to fall, right? It

is an enormous amount of domestic repression at home is going to be Putin’s response to this on the part of Biden, number one.

I would say that where the concern is right now and where you see President Biden, I think, trying to be a voice of restraint, to a certain extent, is

there’s this enormous risk that Putin escalates further, that the more he backs himself into a corner — in fact, his history and methods suggested

that he may well escalate his desire, clearly stated, to reassemble pieces of the old Soviet empire.

And so that’s why you had President Biden from the beginning saying, we’re not going to send U.S. troops to fight in this conflict, but — we do not

want World War III. You see a lot of resistance to calls for, say, a no-fly zone.

And so, to me, that is kind of the most anxiety-producing and uncertain thing, is, how much more escalation will you see from Western allies,

because people are so horrified, understandably, at what’s happening?

MARTIN: How do you read whether the administration really has support, bipartisan support, for the moves that he’s making here?

GLASSER: Yes, I think that’s an excellent question.

I do believe there is strong bipartisan support for Ukraine. And there has been, by the way, for a long time, even through the previous Trump

administration. And so the president has proposed a big new — I think $10 billion was the number being thrown around — aid package for Ukraine that

would include both military and humanitarian aid.

I expect that there would be overwhelming bipartisan support in both the House and the Senate once that does come to the floor, presumably pretty

quickly.

However, part of the kind of public theatrics that you saw the other night at the State of the Union, I do, think is misleading. The Republicans

really are a bit panicky right now, because, in the lead-up to the war, what you saw really was the emergence of a shockingly large pro-Putin wing

of the Republican Party led by the former president himself, Donald Trump, who, as everybody knows at this point, right, has been sort of praising

Vladimir Putin for years, sucking up to him, and concurrently adopting his view of Ukraine.

I think that it’s sort of been forgotten in all the chaos and crises, understandably, of the last few years, but Donald Trump was impeached

because he tried to blackmail the now international hero president, Volodymyr Zelensky, by with — literally by withholding the weapons that he

needed to fight off this very kind of Russian invasion scenario.

And he called President Putin’s moves in Ukraine genius literally days before the missiles started flying. And so the Republicans, seeing this

enormous groundswell of support, are panicking over the idea that the leader of their party, whom they refuse to disavow, has clearly got this

big faction of people.

So I think that’s why you saw a real urgency on their part to make sure they were applauding that part of Biden’s speech and standing up. We will

see, when the dust settles from this horrible conflict, how much of that pro-Putin faction exists or whether the war actually wipes that away.

MARTIN: How impactful do you think was President Trump’s, I don’t know how else to put it, sort of kowtowing to Putin over these last four year?

GLASSER: What’s remarkable and really regrettable is that it’s — this is not just a few comments about Putin being a genius a couple of weeks ago.

This is years’ worth of Trump and his allies in the United States, and, by the way, in parts of Europe as well, far right nationalists, praising

Vladimir Putin, seeing him as this sort of avatar of a different political course,. Republican voters have followed Trump, to a kind of shocking

degree, not all of them, but, again, there’s a significant faction they have.

And, to me, the indicator that really just hits in the gut is that Americans are so divided. Polls have consistently shown that Republican

voters — Putin is unpopular with Republicans and Democrats in the U.S. so let’s be clear about that. But he is far less unpopular with Republican

voters than Joe Biden, the president of their own country, and like, not by a little bit, by like 20 points.

And so that’s a shocking indicator. But what I would say is that it’s still hard for me as well to understand, as an American, how there could be a

large segment of our society that would be supporting Putin. One, they may not understand fully the nature of Putin’s dictatorial regime, the

absolutely suffocating world of corruption and control that he’s reimposed inside Russia.

So that’s not necessarily something that you would think about every day if you’re an American. Number two, look at our society. I would recommend to

read about the period before the United States entered the Second World War, and look at the history of the America First movement. Look at what a

large segment of American society was, actually following Charles Lindbergh, not just resisting entry to the war, but actually saying

admiring things about Hitler’s strength and the like.

That’s a dangerous analogy to make. So I’m not saying it’s that the exact same thing, but, politically, that dynamic resonates, I would say.

MARTIN: Let’s talk a bit more, though, about how we got to this point and what the U.S. role has been in getting to this point.

I mean, you have written quite often about the fact that the U.S. has misread Putin and his intentions for years, that, for some reason, American

administrations, successive American administrations have either — well, you tell me. Did they not take him seriously? Did they misread his

intentions? Can you just talk a little bit about that?

GLASSER: Yes, I think that’s a great question.

In a way, Americans historically have tended to layer on some of their own ideas and perceptions onto Russia and onto Vladimir Putin for two decades.

And I was stationed there in Moscow at the beginning, the first four years really of Putin’s tenure as a leader.

And for much of that time, there was a real debate in the United States over those who saw him, as former Vice President Dick Cheney, actually very

clear-eyed, said to a colleague right when he ascended. He said: I look at that guy, and I see KGB, KGB, KGB.

And you know what? He was right. But there was also President George W. Bush, who looked into Putin’s eyes and saw someone who he could do

business, who was a modern, different kind of leader.

And so there was a willful desire at times to see the Putin we wanted to see, rather than the Putin who told us in 2005, right — 2005, Vladimir

Putin said, the breakup of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.

You know what? That had nothing to do with NATO expansion for Ukraine, which, by the way, wasn’t even a topic of conversation until years later,

right? And, again, it just — it was unthinkable to many people that we would end up where we are. And, of course, that’s true of all wars. But, in

this case, there was example after example, and not just the Bush administration.

The Obama administration, I think, really misread the situation with Putin, because he had just militarily marched into Georgia next door in 2008. And

yet, months later, the Obama administration came in and wanted to have a reset and embraced a kind of fantasy version of this, in which there was

going to be a reformer, Dmitry Medvedev, temporarily in the president’s position, and they were going to do business with him, and there was going

to be a different path forward.

But the lesson that Vladimir Putin got from that was, hey, I had a war of aggression against a neighbor, and, really, there was no long-term damage

to me.

And, unfortunately again, there’s years worth of things like this.

MARTIN: How would you describe President Trump’s relationship with Putin? What was his sort of assessment of him?

Do you have a theory about what that was about and what animated that?

GLASSER: It was very clear that there was a Trump administration policy that wasn’t all that different from what you might have seen from any

administration. And so, we did continue the sanctions on Russia that existed after the 2014 takeover of Crimea. We did provide defensive weapons

like the javelins to Ukraine. That was actually over Trump’s objection.

And that’s the thing, Trump did not support his own administration’s policy. He had a very hostile view with NATO, and his aids and advisories

repeatedly had to talk him out of actually pulling out entirely. I don’t think people understand that. It wasn’t just rhetoric from Donald Trump

about NATO being obsolete.

He came very, very, very close including in the summer of 2018, he explicitly told his then national security adviser, John Bolton, his then

White House chief of staff, John Kelly, that he was going to pull out of NATO, and they made a desperate last-ditch effort to stop him from doing

that.

So, there were many advisers, including Bolton who stated publicly that had Trump had a second term in office that he was going to proceed with blowing

up the NATO alliance. So, that’s number one. Those are facts.

Number two, Trump not only embraced Putin as a strong man and a strong leader and, you know, a kind of figure of veneration and admiration, he —

and refused to take many steps that his advisers urged him to take regarding Putin, but he also adopted Putin’s view of Ukraine.

The record, the sworn testimony in the impeachment trial was very clear that Trump did not believe that Ukraine was — he called it consistently a

corrupt country that doesn’t support me. He adopted Putin’s view that it was totally fine for Putin to have illegally annexed Crimea because he

said, well, you know, those people there, I don’t think they wanted to be in Ukraine anyways.

And so, he would amplify the Russian need disinformation, conspiracy theory that it was not Russia, but Ukraine that actually interviewed in the U.S.

2016 election, which was always an absurd and untrue conspiracy theory. So, the record, again, is absolutely clear. It is not ambiguous. It is not hard

to figure this out. It’s not that they’re forgetting. It’s that they don’t want you to remember.

MARTIN: You wrote a book about Former Secretary of State James Baker. He had a desire as the Soviet Union was collapsing to get a handle on the

nuclear weapons scattered throughout the Soviet states. Why did he want to do that? Why did he think that was important? And what’s the relevance of

that to today’s moment?

GLASSER: Well, that’s right. So, a big part of the Soviet nuclear arsenal was stationed in Ukraine when the Soviet Union unexpectedly collapsed. And

so, it became a priority both of the George H.W. Bush administration with Jim Baker and then, the subsequent Clinton administration to make sure that

there was really only one nuclear power that they were dealing with, and this was the enormous subject of negotiations. It was seen as crucial to

the security of the world going forward. It takes enormous resources, of course, to maintain a nuclear arsenal.

You don’t want to proliferate the number of powers you have. It was a real huge priority, and seen as a great success of American diplomacy that we

were able to negotiate, you know, essentially the return of those weapons and Russia being the only successor, nuclear state.

In exchange for that, there was the Budapest Memorandum in which Russia agreed to guarantee the sovereignty and independence of those states that

gave up the weapons including Ukraine. So, Russia is illegally violating a treaty itself committed to. And, of course, for Ukrainians, it feels like a

double betrayal, right? They agreed to do the right thing for world security, gave up their nuclear weapons, and here they are, if they had

nuclear weapons, Russia probably wouldn’t be invading them, right?

And so, it’s a tragedy, you know, for Ukraine. It’s a tragedy for the international system. But one other point that I’ve been thinking a lot

when it comes to Jim Baker and the end of the Cold War, he and President George H.W. Bush were often criticized here in the U.S. for moving too

slowly, for exercising too much restraint. When it became clear that, you know, what Reagan called the evil empire was unraveling, Americans, just

like there are today, actually, you know, cheering on Ukrainians and hoping against hope that they would succeed.

At that time, Americans were thrilled at, you know, this sort of eruption of freedom and democracy behind the iron curtain, and they wanted Bush and

Baker to do more, more, more. And Baker and Bush were very concerned not to alienate the Soviet superpower when it had all those nuclear weapons and

could destroy the world. And so, that tension really — there’s an echo of that today, although, of course, we’re seeing that tragically the history

reversed itself.

MARTIN: Did that memorandum commit the West to certain obligations in exchange for the Ukrainians giving up their nuclear weapons, and what’s the

relevance of that to the current argument about what the U.S. and its allies should be doing here?

GLASSER: Yes. Absolutely. It meant that we were guarantors as well as Russia to the independence and security of Ukraine. And, you know, so,

clearly, we’ve learned that Russia does not keep its word. Clearly, we’ve learned that it is willing to rip up an international agreement, which it

signed apparently not in good faith.

You know, but the question is also on the U.S. We talk about an international system. We remain the world’s strongest superpower, but if

we’re unwilling to defend that system when its core principles are being broken, of course, that is an enormous blow to U.S. power and prestige as

well. You’re absolutely right about that.

And so, we have, in effect, chosen among terrible competing demands, and what we’ve chosen is at the moment to say our commitment to NATO is

sacrosanct, and you know, if you move one inch into NATO, Vladimir Putin, you know, our Article 5 commitment to defend all of those members will be

met. But we’ve chosen that at the expense of the broader principles of international law and sovereignty that we also are committed to.

MARTIN: Susan Glasser, thank you so much for talking with us.

GLASSER: Thank you.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: And added to that, of course, we heard earlier that Putin does not even recognize Ukraine as a state or a people.

The sports world has also been rocked by this war, with many Ukrainian and Russian athletes deeply affected. Many are using their platforms to express

despair at what’s happening, including the tennis legend Serena Williams.

Early this week, we brought you a rare interview about her plans for Serena 2.0. Her venture capital fund, investing in diversity. But we also talked

about her extraordinary life and career. And her younger years chronicled in the Oscar nominated film “King Richard,” which charts the extraordinary

power behind her success, her father and her family. Here’s a clip.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WILL SMITH, ACTOR: When I was your age, I used to have to fight every day. If it wasn’t the Ku Klux Klan or the police or the white boys from the next

town, somebody was always beating on me for something, and I ain’t had no daddy to stand in their way. This world ain’t never had no respect for

Richard Williams, but they’re going to respect you all. They’re going to respect you all.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Will Smith there, and here she is, Serena 2.0.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Serena Williams, welcome to the program.

SERENA WILLIAMS, 23-TIME GRAND SLAM TENNIS CHAMPION: Thank you.

AMANPOUR: We’re doing this in the most extraordinary moment, all around us people have been, you know, professing solidarity with Ukrainians under

attack. Do you have a feeling about that at this moment?

WILLIAMS: You know, I think right now, the world is in such turmoil, and when you look at what’s happening in the Ukraine and Russia, it’s just sad

to see, you know, the attacks and all of that. So, it’s just — when anytime human life is involved for me, it just something that makes me

really kind of just heavy and sad and not feeling super whelmed.

And so, human life, I think, is so valuable. And it doesn’t matter who you are, where you’re from, it should be amazing and should be a value. So,

that’s — it’s good to see so many people coming out and speaking their truth, and it’s just — honestly, just really sad to see.

AMANPOUR: So, I have to ask you about your tennis career. Are you still committed to beating that record and beating Margaret Court and getting the

magic 24?

WILLIAMS: You know, I’m committed to me right now. I love tennis and I love, you know, what I do. And right now, I just had to — I have to commit

to me. And what does that mean? I don’t know. I still play tennis, obviously, and I still train and, you know, but I think I’m the kind of

person who’s like, well, honestly, I should have been at like 30 or 32. So, that’s kind of how I look at it. But you know —

AMANPOUR: So, you feel you’ve done it in some sort of way?

WILLIAMS: I haven’t done.

AMANPOUR: No?

WILLIAMS: I haven’t done it at all or else I would have done it, right? Let’s just — that’s what it is. But I don’t know. I should have had it.

Really, I’ve had many opportunities to have it, but I’m not giving up to answer your question.

AMANPOUR: That’s amazing. It is actually amazing because you’ve gone through such a lot and wear and tear on your body as well. You couldn’t

take part in the Australian because of injury. Will you be at Paris at the Ppen?

WILLIAMS: Well, Paris is one of my favorite cities, and I actually love the clay. So, I will — we’ll see what happens. Hopefully, my body — if my

body is holding up, then I’ll definitely be there.

AMANPOUR: So, I’m obviously asking you this question, but does it bum you out? I mean, does it tick you off that people keep asking you this

question? Is it too much pressure? Is it unreasonable? Do you think that you’ve had enough of people asking you this question about the record?

WILLIAMS: As our friend says, pressure’s a privilege.

AMANPOUR: There you go, Billie Jean King.

WILLIAMS: You know. What’s the alternative is having someone ask about no record, you know? And I think that’s a privilege. I would rather you ask me

that, to be clear, any day, you — anyone is allowed to ask me that any day as opposed to the alternative of having like three or six or 10 or 15.

AMANPOUR: Yes, yes. Or — yes, yes.

WILLIAMS: You know, so I enjoy that.

AMANPOUR: Good. Let’s talk about “King Richard.” It has just, obviously, been Oscar nominated for best actor for Will Smith who plays your father,

for best picture. It just won — Will Smith won the SAG Award for best actor beating out a whole load of, you know, Benedict Cumberbatch and

Javier Bardem and all of that. How do you feel, firstly, about that, the impact that it’s having amongst viewers, but also amongst the Hollywood

adjudicators, so to speak?

WILLIAMS: Amongst my colleagues.

AMANPOUR: Is that what you are now, a Hollywood colleague?

WILLIAMS: Well, you know, I’m an Oscar nominated, you know, pretty serious.

AMANPOUR: I love it, sorry, forgot to say that. Yes.

WILLIAMS: You know, when we started this long before, we were shooting this movie before COVID started, and we never really thought about the impact

that it could have. And you know, obviously, we thought about it. We thought, OK, this is the goal, and, you know, we want to win awards with

this movie.

We want to impact lives. And still I kind of feel like I’m going to wake up from a dream because it’s amazing, and Will winning the SAG Award, and

“King Richard” him being honored for my dad, who is the reason we’re here today, quite frankly, it just seems like, you know, I’ve done so much in

tennis, and I’ve done so much.

And who could have thought that it could still continue — that the career could still continue on and there could still be transformations in one’s

career. And yes, I was — we’re really excited about this.

AMANPOUR: There’s so many levels to it and so many questions about it. But first, I want to ask you the obvious question that everybody wants to know.

It gave a completely different world view of your father.

And I wonder whether that was one of the intentions because, as you know, and I don’t have to tell you, he has been viewed in public as, you know,

the father who pressured his daughters, this sort of mad cap eccentric, you know, he’s very flamboyant, and he has a whole public persona created in —

you know, over the years he’s been coaching you and, in your box, and all the rest of it.

What did you want people to know about your father by investing so heavily in this film about him?

WILLIAMS: It was important for us to tell the truth and the protection that my dad had around myself and my sister and our family together, it wasn’t

just one thing. It was my dad. It was my mom, it was our family, and all the work that we put into our career. So, that was super important for us

to just have the truth be told.

And unfortunately, entering a new sport where it’s predominantly, you know, white and having my dad have like this villain character when it just

wasn’t true, just having to deal with that my entire career from day one to — you know, to the very end was just really important for us just to tell

the truth. And it was a good moment, and I think people could see that the reason we probably have such a long career and the reason we do love what

we do is because we had so much support.

And so, many times you hear the dad story about how, you know, up to have pressure on your kid and then the parents and the children, they just go

separate ways, and they don’t speak, and then, the relationship is really torn after that, and that wasn’t us at all. We had the exact opposite

where, if anything, my dad, to this day, is like, if you’re hurt don’t play, don’t do this. I’m like, dad, I’m OK.

And so, it was important to get that story out there for us and to also my mom to have this story of what an intricate role she played in our lives

and in particular, my career. And so, that was really important for us.

AMANPOUR: So, it is interesting because the film mostly is about Venus. She was number one and your dad had a plan, again, it’s just unbelievably

stupefying to see that he had this 78-page plan on how to win with his, I guess, children, I guess he didn’t know he was going to have daughters,

before you were even born. And then, he was very methodical about which one would go first and which one would go second. It’s quite staggering to see

that level of planning and discipline and vision.

WILLIAMS: Yes. So, I’m a planner myself, and I think it’s innate. I think it comes from my dad. Yes. So, I think the film is definitely not about me,

and I love that.

AMANPOUR: Yes, exactly.

WILLIAMS: Because it’s like, great, I get to take a step back and just like enjoy and kind of watch. And it’s definitely more focused on my dad and

then, Venus’ career because Venus actually came before me. And it was just so good to see all the steps that we had to take and all the planning that

went into, you know, what the vision.

You know, in order to be an athlete, especially in a single sport, it takes a lot of work, and it takes a lot of dedication, and I don’t — like, I

look at my daughter, and I say, wow, I don’t think I could do what my dad did every single day. It’s a lot of work. And it takes a special kind of

person on both ends, whether it’s the child or the parent, it takes a special person, and I think you get to see all of that in the film.

AMANPOUR: And you said your mother, particularly, was instrumental in launching your career.

WILLIAMS: Right.

AMANPOUR: For those who haven’t seen the film, what do you mean?

WILLIAMS: So, my sister was much better than me. I was not very good growing up. And so, everyone was focused on Venus, and then, in the film it

goes into that, how when we had an opportunity to have better coaches, they saw that Venus was the one and just, you know, that maybe I should just sit

on the sidelines.

And so, that was devastating for me. And actually, devastating was helpful because if that hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have had the career that I had

because I felt like I just had to prove and just to — I had to win.

And so, being cast aside, you know, I just had to work with my mom. I didn’t get to work with the prestigious coaches or anything. And my mom

made me tough mentally, and made me really strong mentally, and I spent countless hours that I have to admittedly I hated every second of them

because she was so tough. But I now enjoy — if I could go back, I would do even more hours with her.

AMANPOUR: On the court?

WILLIAMS: Absolutely.

AMANPOUR: Wow. I mean, that is a story that not many people know. Again, what comes out, is — as I say, the public persona about your dad was the

pushy dad, right? And yet, in the film, you see how many times he actually stopped you, Venus, from being, whatever, assaulted by the press. I don’t

mean assaulted, I mean, you know, pressured by the press.

WILLIAMS: Oh, you’re the press. There you go. Now, since you said it, I got to —

AMANPOUR: I don’t assault.

WILLIAMS: Just totally kidding.

AMANPOUR: I know, I’m kidding you too. But he stopped.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: You know, he did actually protect your vulnerability as children as well as pushing you as athletes, which is a very difficult balancing

act.

WILLIAMS: Yes. And that was — it was such a good thing for a dad to do, to be there and protect his children because when you have a child, your job

is to protect them. And he did the best that he could. And you know, now, people realize that it was the right thing to do, but at the time, people

say that it wasn’t.

And he pulled us out of junior tennis because the parents were — I didn’t know this, I was too young, but the parents were really hard and they would

— there was a lot of awful things going on that we didn’t see, and he just — it hurts —

AMANPOUR: Hard on their kids?

WILLIAMS: Hard on their kids in ways that you can think. It’s just the worst things. They would beat their kids, I remember that. But —

AMANPOUR: Really?

WILLIAMS: Yes, it was really, really bad. It was awful. And so, that’s why he pulled us out of that. In the film, you can see him — it doesn’t really

go into detail of that, but you can see him pulling us out of those tournaments because it was just a platform that we didn’t — he didn’t want

us to be involved in.

AMANPOUR: And the race factor, obviously. I mean, obviously you guys stand out because you’re the two great black female champions out there. Gibson,

of course, was the trailblazer. But nonetheless, it is, as you said, a white sport.

How did you perceive that? How did you get over that? How did your father deal with that?

WILLIAMS: So, we changed it from being two great black champions to being the best ever, period. And that’s what we did. We took out color and we

just became the best. And that’s — records are not like it is proof, and that’s — it is what it is. We changed the sport. We changed the fashion.

We changed how people think. We changed how people think in business, before when we played tennis and we wanted to do something different, it

was frowned upon.

And now, I have two amazing companies. One we came to talk about, Serena Ventures, and all because of what we did to change the sport. And now,

every athlete, it’s almost weird if you’re not doing something else now. It’s like, well, why don’t you have a plan B or C?

So, we never looked at it as a color thing. We knew that we were entering an all-white sport, but for us, it was like we’re entering tennis, and

we’re here to win. And yes, we had to play harder and we had to be better, but it made us better. And at the end of the day, everything — every time

we faced a challenge and every time we overcame that challenge, it created Venus and Serena.

AMANPOUR: But you did, and I’ve watched many of your matches live in various different tournaments. You have borne the brunt of audiences, your

father has as well. Occasionally, he’s being booed. You remember, I guess, it was Indian Wells, and there was, you know, a horrible incident and you

didn’t play at Indian Wells for a good 14 years or so. And sometimes you have shown anger on the court, and you have, you know, you’ve had to —

well, you have had booing on the court as well.

And I just wonder what you think about that. Not just as a black athlete, but also as a woman and whether you think some of the others have, you

know, had the fines and punishments that you have had. For instance, we just seen Zverev, I mean, literally with his racket banging the umpire’s

chair to the point that the umpire had to move his legs out of the way.

WILLIAMS: Yes.

AMANPOUR: How do you — talk to me about that. What happens? What cracks?

WILLIAMS: What cracks an individual or —

AMANPOUR: Yes, that. And then, the difference between maybe how you were treated and how some others were treated.

WILLIAMS: Yes. I think everyone is different. Like Venus is so frustrating playing her because she’s like so even keel. She’s just like — I’m like,

why aren’t you angry, and me, I’m total opposite. I’m just like, ah, you know. It’s just my personality. I think everyone is different.

And it’s not necessarily about cracking. I think it’s just more about passion and it just boils down to your personality, like I am who I am on

the court and off the court, I’m very passionate about what I do. I’m passionate about everything.

And so, that answers that side. But there is absolutely a double standard. I would probably be in jail if I did that, like literally, no joke. So,

yes. I mean, I was actually on probation once. What’d I ever do to get on probation.

AMANPOUR: What incident was that?

WILLIAMS: Yes. You know what, we’re not going to go there.

AMANPOUR: OK. We won’t go there.

WILLIAMS: We’re not going to go there.

AMANPOUR: But there is a double standard and you felt that through your career?

WILLIAMS: It absolutely is. Absolutely. You know, you see that when you see other things happening object tour, you’re like, wait, if I had done that.

But it’s OK. At the end of the day, I am who I am, and I love who I am, and I love like — I love the impact that I’ve had on people. I love the impact

that I continue to have on people.

Now, the impact I can have on people through companies that I invest in and having an opportunity to invest in women and people of color and that,

like, that is, if I didn’t have the passion that I have on the tennis court, I wouldn’t have passion for what I do now. And I accept it, and I’m

excited to continue to have that passion and, yes.

AMANPOUR: Serena Williams 2.0, thank you for joining me

WILLIAMS: Serena Williams 2.0, thank you for having me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

AMANPOUR: Serena Williams owning it and giving back, paying back.

And finally, Russia’s only independent TV news channel is no more. We talked about it earlier, and it did not go quietly. TV Rain was forced off

the air on Thursday amid the Kremlin’s media crackdown. Staffers walked off the set defiantly saying, no to war. And as a final act, the network aired

just a few seconds of Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake.” It was a reference to the 1991 coup attempt against the former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

During that time, the ballet aired on a loop indicating the country was in deep trouble.

That’s it for now. And if you ever miss our show, you can find the latest episode shortly after it airs on our podcast. On your screen now is a QR

code, and all you need to do is pick up your phone and scan it with your camera. You can also find it at cnn.com/podcast and on all major platforms,

just search Amanpour. And remember, you can catch us online, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Thank you for watching, and good-bye from London.