Read Full Transcript EXPAND

BIANNA GOLODRYGA: Hello, everyone, and welcome to “Amanpour and Company.”

Here’s what’s coming up.

(BEGIN VIDEOTAPE)

GOLODRYGA (voice-over): In Geneva, President Biden calls Russia and the U.S. two great powers. But, at home, how great is life for ordinary

Russians? I will ask Ekaterina Kotrikadze from TV Rain, Russia’s only remaining independent TV channel.

Then: Havana Syndrome, the mysterious condition crippling American officials. A former CIA agent on the brain injury that ended his career.

Plus:

ALEXANDER BETTS, AUTHOR, “THE WEALTH OF REFUGEES: HOW DISPLACED PEOPLE CAN BUILD ECONOMIES”: Migration has become the proxy issue for just about

every political grievance of our time.

GOLODRYGA: How coronavirus intensifies the global migration crisis. Oxford Professor Alexandra bets on what he calls the defining challenge of the

century.

And:

ANNETTE GORDON-REED, HISTORY PROFESSOR, HARVARD UNIVERSITY: It’s incredibly important for us to remember that particular day. It wasn’t the

end of all kinds of problems, but it was an advance in democracy, I think.

GOLODRYGA: Walter Isaacson talks to historian Annette Gordon-Reed about Juneteenth, America’s newest national holiday.

(END VIDEOTAPE)

GOLODRYGA: Welcome to the program, everyone. I’m Bianna Golodryga in New York, sitting in for Christiane Amanpour.

While President Joe Biden told reporters that he came to do what he wanted to do, some veteran Putin watchers say the Geneva summit was a major win

for the Russian president. By meeting with Biden as an equal, Vladimir Putin drives up his standing back in Russia.

While he devoted quite a bit of time addressing some of the current challenges gripping the U.S., from racial injustice to crime and the

January 6 insurrection, he avoided the issues facing his own constituents back home, and there are many. Food prices are spiking, inflation is

surging in a country where one in every seven people live below the poverty line.

Meanwhile, a new coronavirus wave is rising, and Moscow’s mayor declaring this a non-working week to help curb the spread of the disease. But back in

Geneva, Vladimir Putin managed to stay philosophical about at all, even channeling Leo Tolstoy.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

VLADIMIR PUTIN, RUSSIAN PRESIDENT (through translator): There is no happiness. There’s only a mirage of it on the horizon. So, well, cherish

that.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: Even as Putin face the world press yesterday, he was actively controlling the message back home.

He barred TV Rain, Russia’s only independent news channel, from the press pool in Geneva. Why? Well, because TV Rain covered protests for jailed

opposition leader Alexei Navalny impartially, as journalists do.

With legislative elections coming up in September, the Kremlin is doing all it can to keep Navalny out of the public eye.

Ekaterina Kotrikadze is the news director and anchor at TV Rain. And she is joining me now from Moscow.

Katya, welcome to the program. Great to have you on.

So, let’s get to the results from this summit. There had been a lot of speculation as to whether or not and debate, really, as to whether or not

it should take place, whether it would be rewarding for Vladimir Putin. It seemed that Joe Biden sensed this and was a bit sensitive about it and said

that he had the backing of all of the European leaders going into this meeting.

Now that we know the results of it. What is your take?

EKATERINA KOTRIKADZE, NEWS DIRECTOR AND ANCHOR, TV RAIN: Well, it was really important to meet.

And, of course, I support that they did meet. And it was extremely important to see to what Joseph Biden is speaking, because a lot of experts

and journalists, including me in Moscow in Russia, we understand that he cannot do anything about the human rights violation inside of the country,

but he at least can talk to Putin and remind him that world is watching.

So, it was very important to understand and to see that the American president is not — is not a friend of Vladimir Putin anymore, like Mr.

Trump was before. So it was — for Putin, Trump’s behavior was kind of a cake or a candy and kind of a stimulus to give him an opportunity to do

whatever he wanted, understanding that no one would say a word about it.

So, now the wording from the Biden administration and from the president himself is really a symbol that we’re not alone here, but still we

understand that there is nothing concrete and there is nothing effective, efficient may be done from the American side, because Putin will not take

the recommendations as something get that he needs to follow.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

KOTRIKADZE: So, that’s why we are here. And we understand that it was a really important meeting, but, still, we understand that we need to — we

need to decide and fight the problems inside of Russia with our own power and our own tools that we have here.

And these tools are not enough on this stage. For Putin, it was–

GOLODRYGA: Well–

KOTRIKADZE: Bianna, it was — I’m sorry to interrupt it.

But, or Vladimir Putin, it was — as you have already mentioned, it was like a step forward, like a declaration from the American side that he is a

leader of the very powerful country, that Vladimir Putin is not someone who just sits at the corner anymore, because, from the very beginning, Biden

administration didn’t want to talk to him, didn’t want to meet him.

Now Putin has shown to everyone that he is the guy who is invited to (AUDIO GAP) country, to Geneva, where the American president arrives, especially

for him and talks to him like an equal.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

KOTRIKADZE: So, this was Putin’s main idea and main goal. And he did accomplish it.

(CROSSTALK)

GOLODRYGA: Right.

I mean, on the one hand, Vladimir Putin and Russia is kicked out of the G8. On the other hand, he gets his own summit that many of our other allies

have not received.

But there were red lines that he laid out going into this meeting. And, obviously, one of them included Alexei Navalny. He would not even mention

his name, as he is known to do in Russia as well.

But I was a bit gobsmacked to hear his justification for why the opposition leader is behind bars. Let’s take a listen.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

PUTIN (through translator): This man knew that he was breaking the law of Russia. He is somebody who has been twice convicted. And he consciously

ignored the requirements of the law.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: I mean, he is suggesting that a man who was poisoned at the hands of the FSB violated the law by being flown unconscious — by the way,

Putin allowed him to finally be transported to Germany — and that’s why he is behind bars now.

He said that with a straight face. Is this a sign of paranoia? Or does he actually think this is working for the domestic audience back home?

KOTRIKADZE: Actually, he does.

And if you talk to people somewhere in suburbs, far from Moscow or St. Petersburg or Yekaterinburg or other big cities in Russia, if you talk to

the people who live in villages, they will tell you that Navalny is a gangster or someone who broke the law several times or maybe dozens of

times.

So, this propaganda that they have, Putin and his official representatives of the government, it really does work, because people still watch the

state television, and they still trust the people who talk to them from the screen.

And, of course, this is Putin’s usual tone and usual position when he speaks about Navalny. He has never, ever, ever mentioned Navalny’s name.

And this is his understanding of the right behavior of the president, because he doesn’t want Navalny to be on his level.

Putin thinks that, as soon as he mentions Navalny’s name, Navalny becomes something important. And that’s why he never talks about this person, the

only leader of opposition in Russia, the main leader, I would say, of the opposition in Russia, as this gentleman.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

KOTRIKADZE: But, of course, there are millions of people who know Alexei Navalny, and they understand that this is the person who really fights the

regime.

And the obvious reality is that millions of Russians, they still believe Putin and trust him. But YouTube works, and our TV channel works, and other

independent sources of information, they do work. And more and more people understand that something is wrong here and something is going on. So, they

go and check online, and they get the information. And Navalny is more and more popular, in spite of the fact that he is in jail.

So, going back to their conversation with Joseph Biden, for Russian audience, for our audience, this conversation about Alexei Navalny, and

overall human rights violation in Russia, Bianna, was the main topic, of course.

And I repeat, we were not expecting something to change tomorrow or the day after tomorrow. But, still, we were interested in how Vladimir Putin would

find the words. Maybe it would be something softer than it was before. Maybe there would be something different, maybe some signals, maybe

something that would give us hope that the that the Russian opposition leaders, the people, the journalists, the politicians, the activists, they

would find themselves in a different position after the summit in Geneva.

But nothing has changed. And, today, for example, the — one of remaining, few remaining representatives of the liberal opposition in St. Petersburg,

for example, he is a member of city council, he was detained. So this is the signal, actually. Nothing is changing.

GOLODRYGA: Right. And it’s becoming much more difficult and dangerous for independent journalists and any opposition groups to continue to function

inside of Russia.

There used to be at least a veneer that that was allowed. And now that is off the table.

I’m curious, because your viewers aside, you talked about those Russians who watch state TV and watched Vladimir Putin sort of shine in that moment.

You could see that he relished that hour that he had solo during that press conference.

If Alexei Navalny isn’t a top priority for them, or human rights a top priority for them, then what is? Because, as we mentioned in the intro,

there’s a lot of economic challenges in Russia right now. COVID is once again surging in the country. Inflation is surging. What are people’s views

of Vladimir Putin going into especially these parliamentary elections?

KOTRIKADZE: Of course, coronavirus is one of the main issues here. And they do understand in Kremlin. They do really understand. They acknowledge

that this is a problem for people, because they are losing money, they’re losing jobs, they’re losing opportunities.

They do not walk in the streets freely because they’re kind of — we know that there are restrictions in Moscow on this stage. But the restrictions

are coming in the whole country, as we feel, because of the pandemic crisis in Russia.

So this is a tough issue for the Kremlin, no question. And they will try to make the restrictions as soft as possible. But it’s becoming impossible,

actually, not to take steps, not to do something. And they feel that the trust to the government is on a very low level on the stage, Bianna.

And, for example, Yedinaya Rossiya, the United Russia Party, which is the main party of the government, of course, in Russia, they have 15 percent of

popularity in Moscow and 27 (AUDIO GAP) in the country. This is the lowest level that were fixed during the years.

So, considering that we’re having elections, parliamentary elections in September, this is the situation that they are worried about. Maybe this is

the reason they’re so tough when it comes to the opposition and journalists and independent media. Maybe this is the reason they are doing — and I’m

sure it is, actually — that they’re doing everything they can to stop people from covering the issues and problems in the country, to stop the

politicians to do something, any kind of activities.

And that’s why more and more Russian politicians, unfortunately, opposition politicians, they’re leaving the country, or they just cannot do anything

because they are declared extremists.

(CROSSTALK)

GOLODRYGA: Right. It’s a charade, really. I mean, the laws continue to be changed daily to suit the Kremlin.

I wanted to ask you a question, finally, because, clearly, Vladimir Putin will not give an independent news network like yours time for an interview.

But he did do an interview with Russian state news today.

And he said that he in Russia is ready for further dialogue, if the U.S. is willing. And I’m wondering how much faith you have in that statement,

because President Biden said yesterday that he doesn’t think Vladimir Putin wants a cold war.

But, given all of these problems that you have just laid out, is it not in Vladimir Putin’s arsenal to constantly say, this is not our issue, it’s

because of the West? Isn’t — doesn’t benefit him to continue to keep this tension between the U.S. and Russia?

KOTRIKADZE: I think that, from the one side, yes. But, from another, he really wants to be a part of the big guys’ team, Bianna. He was offended

when he was kicked off from G8, I’m sure. And he was offended when Jen Psaki, the press officer of the White House, said that Vladimir Putin and

Russia are not the main priority from the very beginning of the administration of the 46th president of the United States.

So he wants to be not an ally, but a main–

GOLODRYGA: A partner.

KOTRIKADZE: Main — yes.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

KOTRIKADZE: Someone who the White House thinks about.

GOLODRYGA: Right.

KOTRIKADZE: He doesn’t want to be a (AUDIO GAP). He wants to be involved. And he wants to be the person who discusses with those big guys, and, of

course, with Joseph Biden. He is the highest priority for Vladimir Putin.

He wants to discuss the world issues with him. That’s why he wants–

(CROSSTALK)

GOLODRYGA: He doesn’t want to play by the rules, which is clearly the problem and why he’s in the position he’s in right now.

Katya, we’re going to have to leave it there. But we really appreciate you joining us. And thank you for all the work that you and your colleagues are

doing to spread the news and the daily news and the reality of what life is like in Russia right now.

Katya Kotrikadze, thank you. We appreciate it.

Well, American intelligence officials are circling in on Russia as the likely culprit behind Havana Syndrome, a mysterious neurological condition

afflicting more than 100 U.S. diplomats, intelligence officials and their families.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken ordered a government review of what appears to be directed energy weapon attacks, causing nausea, headaches,

vertigo, and insomnia.

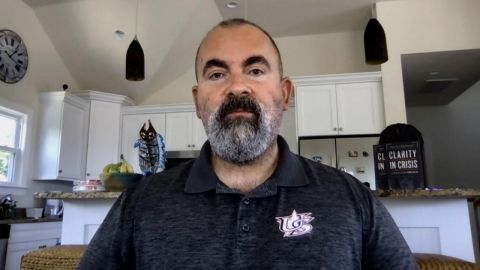

Like many victims, Marc Polymeropoulos says that the government response is too little, too late. Marc ran clandestine operations across Europe for the

CIA. But, after being hit with Havana Syndrome in Moscow in 2017, he was forced to retire from the agency.

His new book is called “Clarity in Crisis: Leadership Lessons from the CIA.”

And Marc Polymeropoulos is joining us now.

Welcome to the program, Marc. Congratulations on the book.

I have been following your interviews throughout your plight here. And what was so frustrating, I could just sense, was how long it took for people to

finally pay attention to what happened to you and how serious this really was.

Can you go back and explain the first time you knew something was wrong? What were you feeling?

MARC POLYMEROPOULOS, AUTHOR, “CLARITY IN CRISIS: LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM THE CIA: Sure.

First of all, thanks for being — thanks for having me on. I really appreciate it.

Look, this has been an incredible journey for myself. And so it started in December of 2017. I was a member of the Senior Intelligence Service at CIA.

I made a trip to Moscow to see our ambassador at the time, Ambassador Huntsman, as well as to meet with Russian officials.

And I woke up early on in the trip — and it was a five-star hotel room near the embassy — but with an incredible case of vertigo. The room was

spinning. I had tinnitus ringing in my ears, a brutal headache, and I knew something was seriously wrong.

And by the time I made it back to the States, I started off on this incredible medical journey, where I was seeing doctor after doctor. And by

about March and April 2018, I had lost long-distance vision. I had terrible vertigo again and some brain fog. So, something — I knew something really

was wrong.

GOLODRYGA: So that was 2017. And, in 2019, CBS’ “60 Minutes” ran a segment on the same topic about two government employees who were neighbors and a

similar experience that they encountered and they felt while they were in China. Listen to this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CATHERINE WERNER, FORMER COMMERCE DEPARTMENT EMPLOYEE: I woke up in the middle of the night, and I could feel the sound in my head. It was intense

pressure on both of my temples. At the same time, I heard this low humming sound and it was oscillating.

And I remember looking around for where this sound was coming from, because it was painful.

MARK LENZI, FORMER U.S. CONSULATE EMPLOYEE: The symptoms were progressively getting worse with me. My headaches were getting worse. The

most concerning symptom for me was memory loss, especially short-term memory loss.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: So, on the one hand, Marc, you hear other accounts in other countries, in adversarial countries where this is taking place. And then

you have the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit initially saying that this is mass psychological illness, others thinking that it’s groupthink.

I even read an account suggesting it could be crickets that’s causing all of this.

Why was it so hard to take these allegations and these claims seriously?

POLYMEROPOULOS: Well, first and foremost, this is quite unusual, of course. We always — we call this an invisible wound. Many of us have said,

subsequent to getting injured, we wish we had been shot. We wish there was a gunshot wound to show people.

But it really was damaging in the beginning when people were discounting many of us. And it happened to me even as — when I was hit in December of

2017, but everything from the FBI’s report, to the medical staffs of, frankly, both the CIA and State Department, particularly when these attacks

first occurred.

It’s a story of pretty gross government incompetence, because, after all, we make a pact as actual national security officials. I did a lot of

unusual things for the CIA, but I always knew that the leadership should have my back if I got jammed up, if something bad happened to me. And that

just didn’t happen.

And that was a really tough pill to swallow.

GOLODRYGA: Well, it seemed that leadership finally did pay attention and take this seriously, in particular, CIA leadership and the confirmation

hearing for Bill Burns. He addressed this head on. Listen to this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WILLIAM BURNS, CIA DIRECTOR: I do commit to you that if I’m confirmed, I will make it an extraordinarily high priority to get to the bottom of who’s

responsible for the attacks that you just described and to ensure that colleagues and their families get the care that they deserve.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: CIA leadership and the director followed up on this pledge?

POLYMEROPOULOS: They have.

And I give Director Burns an extraordinary amount of credit. He’s taken a personal interest in my case and the cases of other CIA officials. He’s met

with us personally. He’s visited Walter Reed’s National Intrepid Center of Excellence, where we were treated.

So, there’s been a huge turnaround. And, frankly, Director Burns deserves a lot of credit.

That said, this is not something that’s been uniform across the government. I think, as far as my colleagues at the State Department, I hear from them

all the time. The State Department is not done the same. And I think they’re lagging behind on this. So we still need this whole-of-government

approach, so all the agencies that are affected, ultimately, so the personnel get the medical care that they deserve.

GOLODRYGA: And we still don’t have the exact culprit, right?

But given your expertise in the CIA, your background and those that you have spoken with and your colleagues that have experienced this as well, do

you think that Russia is behind this?

POLYMEROPOULOS: So, I think there’s a strong — there’s a circumstantial case right now that it’s Russia. And perhaps there’s more.

I have been out of the intelligence community for some time. But I think there’s a history of Russia not only testing, but having these weapons.

Many of the officers involved, particularly at the CIA, who have been affected, were working on Russian operations.

And so I think that you have to you have to look at different actors. But Russia is certainly, I think, top of the list. And, ultimately, we’re going

to find out. The intelligence community is devoting an incredible amount of resources now, as is the Department of Defense.

So, ultimately, we will find out who’s doing this, because they’re doing harm to U.S. government officials, who are working on behalf of the

American people going overseas into harm’s way. And so we have to find out who’s doing this and certainly to stop that from happening.

GOLODRYGA: I’m curious, just given that we had the Biden-Putin summit yesterday, a lot of attention was focused on cyberattacks and other malware

planted at the hands of the Russians, do you have any indication that these attacks were raised as well?

POLYMEROPOULOS: So there are some initial press reports that I have seen that they were. And, of course, that is of significant interest to myself

and many of the other victims.

But I do think that, even if it was not raised, this is something in the future that would be appropriate perhaps for intelligence channels. The

U.S. and Russia, even when it was the U.S. and the Soviet Union, there were always ties and contacts between the various intelligence organizations.

And so I think this is something that certainly should be raised. And, as a matter of course, this is an act of war against Americans. And so we don’t

need to have a court of law determine that it was the Russians to at least raise this with them.

So I think, if it wasn’t raised in Geneva, I believe it will be in the future with — in the intelligence channels.

GOLODRYGA: Well, assuming that it was raised or touched on or at least lumped into the other acts of war that President Biden said he addressed

with Vladimir Putin, President Biden said that he can’t trust that Putin will follow through on whatever was discussed and whatever promises were

made.

But he said he’s going to need three to six months to see if things do change. Do you think that things will change?

POLYMEROPOULOS: No. And I don’t think anyone who has a solid understanding of international relations, and particularly U.S.-Russian relations,

believe that Vladimir Putin is going to change his stripes.

I think this was a marker that President Biden set down. But, ultimately, the U.S. administration is going to have to take a much more aggressive

strategy. I have thought a lot about this. And I think there’s three aspects of what we should do.

One is — and I call it, frankly, defend forward. So one is offensive cyber. We have to hit the Russians back hard. Number two is expose kind of

Russian misbehavior anywhere. And that is something that’s really important, because this would shame the Russians. And the last part is

really working with our allies.

There was an announcement just before the summit about another aid package to the Ukrainian military from the Pentagon. That’s really important. So

there’s a way we have to counteract the Russians. And I think the Biden administration is prepared to do so.

But make no mistake. This summit did not solve any issues.

GOLODRYGA: Marc, let me end by asking, just on a personal note, how this has impacted your life.

You are no longer working, though, somebody at your age, I know I had heard in other interviews that you would have liked to continue working. And it

has impacted you. You were able to write a book, thankfully, but it is limited the amount of time that you can focus on work or anything in

particular. Talk about that.

POLYMEROPOULOS: Sure.

This is this is an emotional subject for me, because, in the past, I look at how my children looked at me. I was in early on in Afghanistan, and same

thing in Iraq. And there was always something happening in the world, and dad would be gone.

And I’m not that same person. And during my treatment at Walter Reed’s National Intrepid Center of Excellence, I created a mask. We do something

called art therapy. And it’s a mask of Superman. And then it — there’s an ice pick going through the center, which signified the headaches I have.

And so it’s been very tough, as someone who really was at the tip of the spear. And I’m not like that anymore. I could write the book. It was a

cathartic experience for me, but I still have these headaches. I have had a headache for over three years, and so something I’m going to have to live

with.

And that’s just who I am. Now. That’s my reality.

GOLODRYGA: Well, Marc, we are pulling for you. We’re glad that you’re getting some treatment now.

Congratulations on the book. And thank you for sharing your story with us. And, most of all, thank you for your service to this country.

POLYMEROPOULOS: Thank you so much. Thanks.

GOLODRYGA: Now, Sunday is World Refugee Day, an international day designated by the United Nations to honor refugees around the globe.

There are now 80 million people displaced around the world, forced to flee as a result of conflict or persecution, climate violence or starvation.

Alexander Betts studies forced migration at Oxford University. In his new book “The Wealth of Refugees: How Displaced People Can Build Economies,” he

says we’re doing migration all wrong. Rather than vilifying migrants, host countries should welcome them for their untapped economic potential.

And Alexander Betts is joining us now.

Welcome to the program.

So, let’s talk about this. You call this — human displacement will be one of the defining challenges of our centuries. And just looking at the

numbers, we can see why. By the end of 2019, there were a record 80 million people, as you mentioned, 40 percent of them children.

What can be done to bring that number down?

BETTS: Well, it is a massive challenge of our era and of our time.

And we really have to confront it in a variety of ways. We see at the U.S. border record numbers of people arriving as asylum seekers. And that

reflects wider global trends. Year on year, we see these increases. And on Sunday, the United Nations high commissioner for refugees will announce a

further increase in displacement numbers and a further increase in refugees.

First of all, we have to address the underlying causes. We have to think about what causes conflict, what causes tyrannical regimes to persecute

people.

But, beyond that, when people flee, we have to provide them access to our territories, we have to ensure that, through access to asylum, access to

resettlement, they can reach safety, they can have a pathway to membership of a community and reintegration into society.

And that’s a common shared duty that today is under threat around the world. It’s been under threat in Europe in particular, with countries like

Denmark and U.K. turning their backs on refugees. It was threatened by the Trump administration.

And it’s not just the rich world. It’s also countries like Kenya now threatening to close refugee camps, countries like Lebanon under severe

economic pressure, in the context of the aftermath of COVID-19, taking more refugees per capita than any country in the world.

So, it’s a dual-faceted problem. We have got to look at the underlying causes. But, given that people will flee and will have to flee in

increasing numbers, we have to safeguard the core human rights that make us civilized countries of admitting refugees onto our territories as a global

shared responsibility.

GOLODRYGA: Yes.

And you talk about in your book that refugees have this enormous untapped potential that you just listed right there. But, in terms of how this plays

out in real life, one case study one could look at is what Germany did and what Angela Merkel did in 2015 and ’16 with the Syrian refugee crisis that

got enormous backlash, not only from Germans, but throughout Europe as well.

Now, Merkel had sort of pitched this not only as a humanitarian cause, but also something that could help stimulate the economy. As she is now leaving

office in a few months, I’m wondering, what was the net result of these past five years? Was the economy stimulated, humanitarian aid aside? Did

these refugees help benefit the German population overall?

BETTS: Well, first and foremost, protecting refugees is a humanitarian obligation.

But we need to change the narrative from just thinking about these people as vulnerable victims to people with skills, talents, aspirations, people

who can contribute to not only our broader societies, but our economies.

Around the world refugees are consumers, producers, entrepreneurs, they’re employers, they’re borrowers, lenders, they’re the founders in our

societies, and we see that in every part of the world. So, much of my work, I focus East Africa. And there is a real development contribution that

refugees can make the host of societies when they’re given the opportunity and the right to work.

Now, in the case of Germany, it was a challenge in the initial years. Many people arrive from a very different society and economy, notably the Syrian

economy, and integrating into a high skilled, highly standardized economy like Germany was difficult. But the government took a decision. Angela

Merkel decided it would invest in the human capital of those people, give them access to education, vocational training, insert them into the labor

markets.

And what we have seen is over time, Germany is reaping the rewards of that. Syrian refugees are integrating in Germany. And I think no one would

pretend it’s been easy for Germany to admit well over a million refugees, but it’s managed and it’s recognizing now that there is that contribution

despite some initial skepticism.

GOLODRYGA: As you sit there in the U.K., I’m wondering just personally your reaction to the rise in nationalism that we’ve seen though from that

flow of migrants and the refugees, in particular from Syria and perhaps even leading to Brexit. That seems to be counter to the whole argument

you’re making.

BETTS: Well, it is a real challenge. We recognize that in 2016, in particular, there was a rise in populous nationalism across Europe, in the

United States and around the world. Right-wing governments were elected in many places, there was increased support for anti-immigration votes and

that partly builds on the aftermath of the 2015-2016 European Refugee Crisis, as it was known. And that did contribute to, for instance, Brexit

in the U.K.

So, what we’ve got to look for is sustainable refugee policies. Refugee policies that, yes, make refugee rights as an absolute obligation but also

reconcile that with taking the public, the electorate, the voters with states and governments on that journey, and a key part of that is to say,

well, absolutely have to admit asylum seekers and receptor (ph) refugees. We can’t take all of them in the world. 86 percent of the world’s refugees

are actually in low- and middle-income countries. They’re not primarily in Europe and North America.

And it’s in those poorer regions of the world, countries like Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia, Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Iran and Pakistan, those are the

countries that has most of the world’s refugees and that’s where we have to focus. Not just with humanitarian assistance, not just on food, clothing

and shelter, but development systems that nurtures job opportunities, educational opportunities. And if people can have access to meaningful

work, opportunities that nurture their potential where they are, then there would be less need for them to move onwards to Europe, to North America or

elsewhere to rebalance the (INAUDIBLE).

GOLODRYGA: Yes. And you mentioned Jordan, in particular, you know, in 2017, Christiane visited a refugee site, the U.N. refugee site in Amman and

spoke with a family there that had been seeking shelter. Take a listen to this.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

CHRISTIANE AMANPOUR: In this game of human lottery, the weakest often wins. A father moves his face in close for the

mandatory iris scan and he tells us the family fled war and home in Damascus 2013. Mother Om Ali (ph) says her very young children have been

traumatized.

OM ALI: At first, we were moving from place to place for fear of the bombings. Nowhere was safe for us and the children suffered. They were in

constant fear. And whenever they heard a noise, they hid. They started to have some sort of post-traumatic stress.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: I think it’s so important, you know, Alexander, to see the human faces of the suffering, right? It’s not just numbers. They’re every

single family, every single person who is a refugee is going to be impacted for the rest of their lives through this trauma and this experience.

You know Jordan well. In 2015, you created the Jordan Compact and that is where international funds and investment would go into the country in

exchange for work permits. We are now seeing — and it’s not just because of this, but we’re not seeing a very unstable Jordanian government right

now and monarchy. Some perhaps attributing to this crisis. What is your response to why this wasn’t working as well as you had hoped?

BETTS: Well, it highlights the fact that it’s not only countries in Europe or North America that feel the pressure from hosting large numbers of

refugees. We have to support very generous host governments in very volatile regions like Jordan, like Lebanon to make ensure that they can

continue to sustain and be able to host refugees.

That means allocating development aid that benefits not only refugees but ensures that the host populations and the host community share in those

benefits, that citizens of countries like Jordan also enjoy access to better education, health services and jobs.

Now, the Jordan Compact has had a mixed legacy. What it’s achieved was the creation of the right to work, the Syrian refugees in Jordan, something

that hadn’t existed up to that point.

But where it really struggled is to attract additional private sector investment from abroad to create jobs for both Jordanians and for refugees,

to create those meaningful employment opportunities and that’s the challenge that we all face on a continual basis, how to focus those front-

line countries, whether it’s Jordan, Turkey, Lebanon in the Middle East or whether it’s the Northern Triangle states that receive refugees where

displaced people come from and transit through or Southern Mexico.

How do we create sustainable opportunities? And, if you like, create anchors that bring opportunity for people where they are rather than

forcing us to build walls in the way that Europe ended up doing in 2016 and in the way the United States did under the Trump administration.

GOLODRYGA: And a lot of these countries are now facing aging populations as well in another argument perhaps for allowing these younger refugees and

these migrants to bring not only their skill sets to the country and helping the economy but also saving human beings, and there are millions

that are now displaced.

Alexander Betts, thank you so much for focusing on this and bringing us this interview. We appreciate it.

BETTS: Thank you.

GOLODRYGA: Well, now turning to the U.S. For years, black Americans have been pushing for Juneteenth, the end of slavery, to celebrated as a

national holiday. Well, today, that dream is finally realized as President Biden signs it into a national law.

Pulitzer prize-winning historian Annette Gordon-Reed has written a new book all about that historic day on June 19, 1865. Here’s Walter Isaacson

speaking to her about what the holiday means and her own extraordinary story as the first black student to integrate into an all-white school.

(BEGIN VIDEO CLIP)

WALTER ISAACSON: Thanks, Bianna. And Professor Annette Gordon- Reed, welcome back to the show.

ANNETTE GORDON-REED, AUTHOR, “ON JUNETEENTH”: Glad to be here.

ISAACSON: You’ve just written a book on Juneteenth. Explain to us exactly what Juneteenth commemorates.

GORDON-REED: Well, it commemorates the day when United States army general Gordon Granger went to Galveston in June 19, 1865 and issued a general

order number 3, which said that slavery was over in Texas.

This was, you know, two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed, it was after Lee had surrendered in

Appomattox in April and after Lincoln’s death. But the army of Trans- Mississippi had kept fighting and they did not surrender until the beginning of June 1865, and that’s when Granger had gone to Galveston and

make this announcement.

ISAACSON: So, why should it be celebrated as a national holiday?

GORDON-REED: Well, because it was an event in — that marked the end, essentially, of the confederate military operation to maintain the system

of slavery, the way of life in the south. It represents to me, I think, an important day in the union and in the American Union, Texas was part of the

union and then it was brought back into the union, and I see it as a day that marks a human rights advance, the end of a system of shadow slavery

where people were treated as property, that’s something that everybody should celebrate.

I mean, obviously, it didn’t solve all problems, but it was a step along the path, that we can be seeing — we can see it as something that was in

advance in, you know, American life and an in American civilization and world civilization.

ISAACSON: Is it a fitting companion to July 4th?

GORDON-REED: I think so. I mean, that’s — I think they should be seen together, in a way. They — it’s interesting because Granger’s order

mentions equality. It not only says that the enslaved were free, it says that they would then occupy a state of absolute equality, which he didn’t

have to say. It didn’t have to be said, but I think by using that term, using those terms he references, he hooks on to the Emancipation

Proclamation and, as you know, Lincoln used the Declaration of Independence as a basis for creating what he called a new birth of freedom.

So, this notion of equality goes through all of these documents, you know, all of these documents and sort of buttresses the idea that equality is an

important goal as part of the American creed. So, yes. You know, I think it’s incredibly important for us to remember that particular day. It wasn’t

the end of all kinds of problems, but it was an advance in democracy, I think.

ISAACSON: So, enshrined in the notion of Juneteenth is not just the end of chattel slavery but the beginning and the hope for equality and social and

economic terms which was still trying to achieve.

GORDON-REED: Yes. Yes. I mean, that’s — it’s that American creed, the sort of expectation, the idealistic understanding about what America is

supposed to be about is embodied in this, and, you know, those people knew that they had a struggle ahead of them, but they also knew that by law now

it would not be legal to sell their children, to separate husband from wife, to effectuate the dispersal of families, which was the most traumatic

thing about slavery.

I mean, whipping was bad, obviously, working without — you know, for others and not being able to amass, you know, any part of property or amass

any resources that belonged to you, those things were bad. But what enslaved people really felt traumatized about was the separation of

families. And Juneteenth has evolved into a celebration that really is about families, people coming together, and not just blood relatives but

members of the community coming together and celebrating and being together, because people couldn’t do that, couldn’t be assured of doing

that in slavery.

ISAACSON: Your book is a wonderful memoir, very personal, and you describe that coming together on Juneteenth, how you as a kid growing up in rural

Texas celebrated that day.

GORDON-REED: Yes, I don’t remember a time when we didn’t celebrate it, and it was a day for, you know, kids to run around and drink too much soda

water and throw firecrackers. I mean, I can’t — every time I say that I just can’t marvel at the idea that we were allowed to have matches and

firecrackers when we were below 10 years old. I would never let my kids do that, but it was a different time.

And we just — it was fun. It was a lead-up to July 4th, but it was — when I was celebrating it, a holiday that was mainly for black Texans. And so,

it was in our communities that this was done. It became a state holiday, first officially, celebrated in 1980.

But even before then, whites — some whites had begun to celebrate it as well. But when I was a kid, it was very, very much a part of the black

community and it was a day for people to get together, eat food, men played dominos, tell stories, all of the kinds of — you know, to relax. And also,

when I got to be older, think about what the day actually commemorated, and that was the end of slavery. A very serious thing, the end of slavery in

Texas.

ISAACSON: It was very personal for you because you had a small role in the civil rights movement in first grade when your parent his sent you to what

had been an all-white school. You were like the Ruby Bridges of your town. Tell me about that experience.

GORDON-REED: Well, when I got ready to go to the first grade, I had been at kindergarten in what would have been called the black school, Booker T.

Washington School, which went from K through 12. And my parents decided to do something different. They had what was called a freedom of choice plan,

which was put in place as a subterfuge, basically, to try to get around brown and not just in Texas.

ISAACSON: Brown v. Board of Education

GORDON-REED: Brown versus Board of Education that outlawed, you know, separatism, inherently unequal. And this was an effort to — you know, it

sounds good. Freedom of choice, right? Everybody can just choose. But the expectation was that white parents would choose white schools and black

parents would choose black schools. My parents decided to do something different and send me to a white school, and that was despite the fact that

my mother taught at Booker T. Washington, my two older brothers were there in elementary school and they decided to do this.

And they talked, I am told, that there was an agreement that was made that they wouldn’t make big deal about it. No one would make a big deal about

it. I wasn’t escorted to school. There had been threats against my family but they — I probably weren’t thought of as credible. I wasn’t escorted to

school. My father took me and dropped me off. And that first year was tough, in a lot of ways. But my teacher, Mrs. Daughtry, we all know our

first-grade teacher’s names, was fabulous. She was wonderful to me.

And I wonder if it might have been because, not just being a decent human being, but that my mother was a teacher and the teachers had this kind of

camaraderie with one another. But she treated me as, you know, not as any different than other kids. Some of the kids were nice. Some of them were

not. My mother said, at one point, I broke out in hives, which might suggest a stress reaction to some of this. But for the most part, it was —

I loved school.

You know, I loved being there. I loved learning. And so — and I was a good student. I kind of wonder how it would have been if I had been struggling

as a student and that on top of other things, but because I was good at it and I’m a basically even-tempered person, I wasn’t a problem in school, you

know, things went smoothly for me, certainly in the classroom and with the teachers.

As I said, some of the kids were not so nice and some of them who were nice, if I saw them in town and was friendly to them, they would be cool.

And I figured out that they didn’t want to be seen before their parents, you know, being friendly to me. And so, that was a valuable lesson about

race and how it makes people act.

ISAACSON: You had some problems with young blacks in your community too who saw you going to the white school.

GORDON-REED: Yes. About three years after I went to Anderson, the Supreme Court struck down freedom of choice plans and then everybody had to change

schools. And there were people in the black community who were not happy about that because Booker T. Washington was sort of the nerve center of the

black community. You know, teachers were respected members of society. They were leaders in the society. They lived in the community. They socialized

with patients. I mean, it was — they knew each other. There was a closeness there that was lost when integration came.

As good as my teachers were to me, and they were, as I said, Mrs. Gillan (ph) on second grade, those two first two years, you know, they were vital.

They didn’t socialize with my parents. We were Texans but we were really separated by race socially.

So, I recall and I mentioned this in a book, a young boy standing in line next to me and he says, you know, that’s, and he sort of turns around and

starts hitting me in the chest. And I didn’t know who he was, and it was just — I knew why. I knew why he was upset with me, but I didn’t know who

he was and I —

ISAACSON: Why was he upset?

GORDON-REED: Well, he was upset because I — he saw me and was — I didn’t make the Supreme Court do this. He saw me as a symbol of his loss, you

know, that I had caused all of this. You know, now, they had to go to different schools. They had — you know, they were, you know, separated

from their community and —

ISAACSON: Was he white or black?

GORDON-REED: He was black. He was black. So, he knew, you know, that he had lost their teachers. And that’s the other thing, one reason my parents

and my mother, in particular, became somewhat disillusioned with integration, because they integrated at the level of the children, but not

the teachers. All across the south, a lot of black teachers lost their jobs. They were taken out of the classroom or moved around because white

parents didn’t want black teachers over black — white kids.

So, it was integration of the kids but not an integration of the power structure. And indeed, my parents as, you know, suggested, became the

reason for sending me to the school changed over time. When I was adult — an adult, they said, well, we knew the court was going to strike down the

plan and then you’d have to change schools, but I think there were — it was sort of a pragmatic consideration.

But from what I remember of the way people were responding when I was going to those schools, they were idealistic. This is the mid-’60s, there was a

Civil Rights Act and there’s the Voting Rights Act, they saw — they thought that black people were sort of on the move and they were part of

that. They wanted to be a part of it.

But once they saw that it didn’t work out the way they anticipated, they — I think they might have been a little self-conscious about having been so

idealistic about the possibilities with the integration of the schools.

ISAACSON: You wrestled quite a bit with the fact that your mother, in particular, became disillusioned with integration. What are all the reasons

you think went into her thinking?

GORDON-REED: Well, she would say — she had said to me a couple of times, she had gone to college and she went to Spelman and TSU for graduate

school. She said, I went to school to teach black students. They were part — it’s not that she didn’t love her white students.

It’s just that they were a part — she was a part of a generation of people who saw themselves as a sort of a vanguard. Their mission was to help the

black community teach, to help the black community — the old phrase, uplift the race. That’s what people said and that’s what they meant,

literally that, that this is what teaching was supposed to be about.

When they had integration, the mission had to change. I mean, she had students whom she loved. She was good in the classroom and they loved her

too. I’ve heard from a number of them after my book came out who were her students, but it was different because the white students — I mean, she’d

say, you know, we can’t talk to them the way we used to talk to them. You know, when they had black students, they would say, you know, you really

got to do this because, you know, we’re — you know, we have all this and, you know, they’re a part of a mission, they’re part of a — on a journey.

But white student — I mean, the society he been had been made. So — I mean, and she didn’t have to exhort them in that way. And the black

students — sort of a minority of black students in her class at that point, I mean, you know, you can’t single them out for stuff. So, you know,

she loved teaching, she loved being in the classroom, but the mission changed.

And she had been a part of a group of black female — mainly black female, some black male teachers, you know, you could imagine the faculty lounge

would be very different with that group of people than people who had never maybe socialized with blacks before. Some of her white colleagues, she made

great friends among them. But it really took a while to figure out — well, you know the south, to figure out how blacks and whites who had never

socialized together, had small talked together to do those kinds of things on an equal basis.

ISAACSON: One of the things I found fascinating in your book, “On Juneteenth,” was your love of Texas. How much you self-identify as a Texan.

Your family has been there for six generations or so since the 1820s. And you grew up in Rural Texas, experiencing a lot of discrimination, being in

the balcony of the movie theater, having the general store owner treat you poorly. Did you develop, I think, what W.E.B. Du Bois calls a dual

consciousness of being back and being a proud Texan?

GORDON-REED: I think so. I think so. The thing that I — the reasons that I have affection of the state grow out of the feelings that I had with my

family. My mother and my father, my brothers and my grandparents and the people in my community, the thing that happened to me there that were

formative. And now, the fact that there are people there who hated us, who, you know, looked down on us, that doesn’t define those experiences for me.

And I don’t believe that they are the ones who, you could say, own Texas in some way.

I mean, you know, I felt the connection to the place because my family has been there for so long and most of my family is still there now. I mean, we

are not a diaspora family. We — when my relatives moved from the country, they moved to Houston or they moved to Dallas and they moved to Austin.

They didn’t move to New York. I am the outlier here in coming — you know, leaving the borders of the state to go away to New England for school.

So, yes. If you assume — if I’m supposed to hate Texas, I’m — if Texas — think of it as an entity, what I am essentially doing, for me, and other

people can feel differently about this, but for me, that is ceding territory to other people and saying that they are the Texas and I am not.

You know, I’m an interloper. I’m an outsider. And I don’t seed that territory.

I think of myself — I thought of myself as a Texan connected to that place. And other people can have their views about me and about my family,

but I know about what happened to me there, and I know how long my people have been there, and that’s meaningful to me.

ISAACSON: Professor Annette Gordon-Reed, thank you for joining us.

GORDON-REED: Thank you for having me.

(END VIDEO CLIP)

GOLODRYGA: Such important testimony from Annette Gordon-Reed there. She makes Texans like myself so very proud.

And finally, there are diamonds and then there’s this diamond. Take a look at that. The huge gem was found in Botswana and unveiled this week at 1,098

carats. It is thought to be the third largest diamond in the world. And just in case you’d like to put a ring on it, this stone is not for sale. At

least not yet. But just so you have an idea, in 2017 the second largest diamond ever found sold for $53 million. So, I guess you can start saving

now for this one.

Well, that’s it for now. Join me tomorrow when I speak to Andy Slavitt, the former White House senior adviser under President Biden. We’ll discuss what

he says were the Trump administration’s failures on the COVID-19 response, and how today’s major Supreme Court ruling affects Americans’ health care.

As always, you can catch us online, on our podcast and across social media. Thank you for watching “Amanpour and Company” on PBS and join us again tomorrow night.